28 Oct 2016 | Belgium, Europe and Central Asia, Kosovo, Latvia, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Russia

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

Sergey Leleka, a columnist for the pro-government newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda, suggested in an article on 24 October that independent journalists Anton Nosik and Sergei Parkhomenko should be “cured in gas chambers”.

According to Leleka, he wrote the article in reaction to jokes by Nosik and Parkhomenko about the Russian aircraft carrier Admiral Kuznetsov which passed through the English Channel emitting thick black smoke.

After the journalists complained to KP, the media outlet deleted the offending paragraph. However, Leleka’s original post is still available on his Facebook page.

A number of Belgian media websites, including De Standaard, RTBF, Het Nieuwsblad, Gazet van Antwerpen and Het Belang van Limburg were subject to a co-ordinated DDoS attack on 24 October, which temporarily shut the sites down.

A group that calls itself the Syrian Cyber Army claimed responsibility.

“We have attacked the Belgian media outlets that support the terrible actions of their Air Force in Syria,” the group said in a message to the newspapers. It wanted to “shame the Belgian authorities, which killed dozens of civilians in the village of Hassajik near Aleppo on 18 October”.

Belgium’s Federal Prosecutor’s Office has launched an investigation.

Editor-in-chief of Gazeta Express, Leonard Kerquki, received death threats after the airing of his documentary which mentions war crimes committed by the Kosovo Liberation Army.

The documentary, Hunting the KLA, aired in two parts and covers crimes and prosecutions from the war between Serbia and Kosovo at the end of the 1990s. The threats were made after the showing of the second part on 23 October.

The Journalist Association of Kosovo condemned the threats, as did the OSCE mission in Kosovo. “I condemn the threats and calls for violence against Kërquki. Freedom of expression must be upheld and respected in all circumstances,” said the head of Kosovo’s OSCE mission, Jan Braathu. “I call on rule of law authorities to investigate these threats immediately and bring the perpetrators to justice,” he said.

Ella Taranova, a senior producer for Russia Today, was detained by Latvian border guards on 21 October and later deported.

The incident occurred after Taranova was admitted to Latvia and to participate in a conference in a seaside suburb of Jurmala.

Taranova was blacklisted for being an employee of Russia Today, which the Latvian authorities see as a hostile propaganda organ of the Russian government. The head of Russia Today, Dmitry Kiselyov, is blacklisted from travelling to the European Union and other countries under EU sanctions imposed in the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

After her detention, Taranova told journalists: “I did not engage in any political activities nor do I intend to.” She added that she was unaware that she had been blacklisted since 2014 and had attended several such conferences prior to 2014.

At around 6am on 21 October, Russian Investigative Committee (SKR) officers entered and searched the apartment of Ksenia Babich, journalist and spokesperson for human rights international organisation Russian Justice Initiative.

According to Shelepin, SKR officers confiscated a notebook, phones and memory cards.

Babich was also asked to go to the SKR for questioning, Ilia Shelepin, a journalist and Babich’s acquaintance, wrote on Facebook. Babich believes the search is related to the case of Artyom Skoropadski, a press secretary of the Ukrainian organisation Pravyi Sektorwhich, which is banned in Russia.

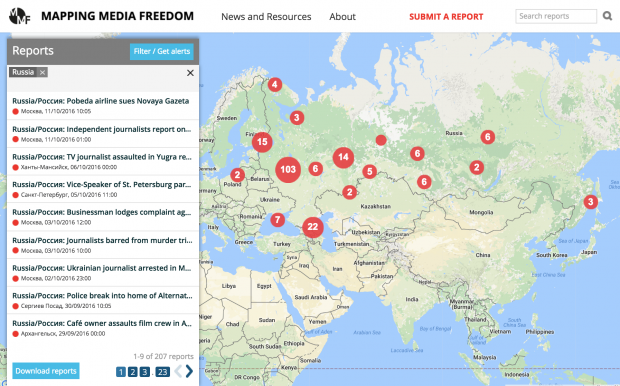

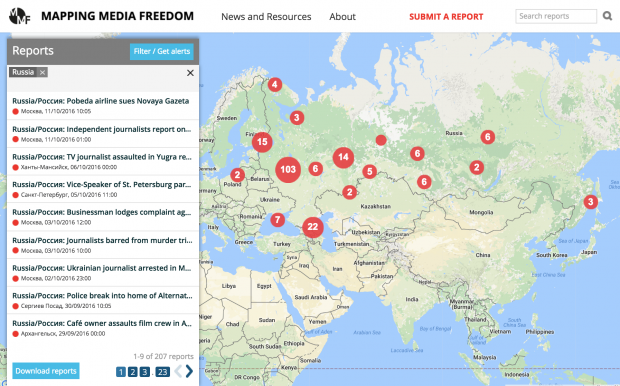

21 Oct 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia

Russia’s recent elections have been described as “the dullest in recent memory”. But as Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom (MMF) project shows there was no shortage of media violations and claims of voter fraud.

On 18 September, the day of the vote, journalists across Russia were denied entry, attacked and arrested while attempting to monitor polling stations.

Rosbalt, a Russian news website, reported several instances of journalists – among them reporters for the BBC – being escorted out of a polling station by police officers and employees of the Vasileostrovsky district administration.

Further reports of journalists’ rights being violated in Saint Petersburg were widespread.

In Siberia, reporters were obstructed even from entering polling stations. A number working for Reuters were denied entry after officials at the location said they needed permission from local authorities but there is no law requiring this of international reporters. A voter claimed the counter used by a Reuters reporter to keep track of people voting was actually a radioactive device, and the reporter should be removed. This was not enforced.

Denis Volin, editor-in-chief of local news site Orlovskie Novosti, was barred from entering a polling station in Oryol. Volin was attempting to take photos of the polling station but officials demanded he stop. Journalists in Russia have a right to take photos and observe voting.

A journalist in Samara was illegally barred from a polling station despite having the necessary accreditation. When the journalist tried to stay for the vote count, officials demanded additional accreditation, which does not exist.

Journalist Dmitri Antonenkov and an activist with the Public Monitoring Commission, Vasili Rybakov, were both detained at a polling station in Ekaterinburg while investigating the illegal use of the Russian state coat-of-arms in polling stations. The pair were detained for two hours and their identification confiscated without return.

MMF Russian correspondent, Ekaterina Buchneva, said: “In general, attempts to bar journalists from polling stations were very common. We saw a lot of reports from Saint Petersburg and Moscow but the investigation by Reuters (they sent journalists to 11 polling stations across central and western Russia) proves that it was common for the rest of the country too, but, unfortunately, remained under-reported.”

Another of MMF’s Russian correspondents, Andrey Kalikh, said: “What is common is that journalists monitoring elections are often threatened if they reveal voter fraud at a polling station. There were dozens of cases in the 2011-2012 election campaign (state parliament and presidential elections) where registered journalists were kicked out, beaten up or otherwise harassed.”

Vladimir Romensky, a reporter for the independent TV channel Dozhd, for example, was involved in an altercation at a polling station in Moscow. Romensky was visiting the station to verify information about voter fraud. Earlier in the day a member of the polling board told Romensky that certain ballots were marked for the United Russia party. A man who refused to introduce himself denied access to Romensky and his crew. While Romensky was inquiring, a nearby police officer called armed guards from the station. The guards demanded Romensky’s paperwork and, despite having all his documents, the guards forced Romensky and his crew out of the location.

In another incident, Fontanka news correspondent Dmitry Korotkov was investigating the process of “carouseling”, a form of rigging elections where a group of selected people vote multiple times in different polling stations. When asked whether or not carouseling is a recent trend, Kalikh said, “No, it is not. It has existed before, the most cases were registered in 2011-2012. But the [Korotkov] case… is one of the most outrageous ones.”

Korotkov received information that voters with a special passport stamp were given multiple ballots at a polling station in the Kirov district. Korotkov was able to receive the stamp and received four different ballots at the station, even though he was not registered for the district. The polling official allowed Korotkov to sign as another voter.

Korotkov reported the incident and the polling board promised to investigate. Instead, Korotkov was detained by police officers on charges of illegally receiving ballots. The police interrogated Korotkov and his case was taken to court on 28 September. The journalist could be facing charges of using someone else’s ballot in a general election; his case is still under investigation.

Buchneva said: “The Fontanka reported that after questioning Korotkov and a suspect, who acted as an election official and gave Korotkov ballots named after another person, ‘the judge apparently had no more doubt, that Korotkov signed for another person not to vote illegally, as it was stated in the police report’. However, it is too early to say that the journalist will not be punished.”

Journalist Dmitri Antonenkov and an activist with the Public Monitoring Commission, Vasili Rybakov, were also both detained at a polling station in Ekaterinburg while investigating the illegal use of the Russian state coat-of-arms in polling stations. The pair were detained for two hours and their identification confiscated without return.

Winning 54% of the vote, United Russia now has a majority in the Duma, allowing them to change the country’s constitution without the approval of other parties.

20 Oct 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, Russia, Ukraine

Andriy Klyvynyuk (right) and fellow activist Eugene Stepanenko in front of a projection of Ai Weiwei’s freedom of expression symbol in London. Photo: Nicolai Khalezin

Ukrainian rock musician and activist Andriy Klyvynyuk spoke to Index on Censorship about his support for popular film director and pro-Ukrainian activist Oleg Sentsov and the other Ukrainian political prisoners held by Russia.

Klyvynyuk, the frontman of the pop group Boombox, was a speaker at Belarus Free Theatre’s Freedom of Expression in Ukraine event at the House of Commons in London, where he called on the British government to demand Sentsov’s release. Sentsov is serving a 20-year prison sentence on charges of being part of a terrorist conspiracy. He has stated that he was tortured by investigators and that a key witness recanted in the courtroom on the grounds that evidence had been extorted under torture. His lawyers describe the case against him as “absurd and fictitious”.

Sentsov faces another 18 years in jail but Klyvynyuk, who drove an ambulance during the pro-EU Euromaidan protests in 2014, is determined that Ukraine will continue to work towards a future free of Russian interference.

“We used to cry but now we are laughing because we are not afraid,” he told Index. “We are only 25 years old as a country, and we are at the very beginning of a road. We want to be open and don’t want to see a great wall. I don’t want to be a big star somewhere, having everything but not being able to travel, speak with you, and that was the point of Euromaidan. We are not for the money, the wealth, houses and cars – it’s not what we want, it’s not the point of life at all.”

According to Klyvynyuk, it is Russia that is afraid. “They are very frightened to lose their dominance, to lose their money, to lose their superpower, in such a way as our mafia lost their power,” he said. “The officials are so much afraid that they invaded an independent state.”

Other speakers at the House of Commons event included journalist and author Peter Pomerantsev, and film and theatre director turned soldier Eugene Stepanenko. A video was shown including messages of solidarity from artists including fashion designer Vivienne Westwood and actor Will Attenborough.

Klyvynyuk welcomed these contributions. Although he does not mix his art with his activism, he feels strongly that those with a public position have a responsibility to speak out on human rights abuses. Those who shut their eyes to it, he says, are “clowns dancing on the tables of dictators”.

“I’m a patriot of course but I don’t think Ukraine is bigger or better than any other country in the world,” he said, calling on the world’s media to refocus on Russia’s behaviour towards its neighbour. “This is why we talk about political prisoners all over the world and wars all over the world. But to forget about situations like that, then everybody says ‘Oh, how are you? Are you okay?’ three years later. I say ‘Hey, stop, you know nothing’, and if you are a media person, if you’ve got followers on your social media, if thousands of people are waiting to hear from you, you should find some time to tell these important things.”

As for Oleg Sentsov, Klyvynyuk’s message was one of hope. “I hope that he won’t be broken inside, I hope that he, all of them, will find strength to live through, and then after we win, go out and not just sit and do nothing but continue their work, what they are here for.”

7 Oct 2016 | Magazine, Russia

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Remembering murdered Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya

In 2002, the well-known Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, was living in Vienna. She had been sent there for her own safety by Dmitry Muratov, editor-in-chief of her newspaper Novaya Gazeta, after she received threats from high-ranking officials over her reports from Chechnya and her criticism of Vladimir Putin’s regime. Her life remained under threat and she was largely confined to her home. She filed this article to Index on Censorship magazine (vol. 31,1) in spring 2002, shortly before she won Index’s Freedom of Expression Award. Four years later in October 2006, she was shot dead in her apartment building after returning to Moscow.

Just before my last trip to Chechnya in mid-September my colleagues at Novaya Gazeta began to receive threats and were told to pass on the message that I shouldn’t go to Chechnya any more. If I did, my life would be in danger. As always, our paper has its ‘own people’ on the general staff and the ministry of defence — people who broadly share our views. We spoke to people at the ministry but, despite their advice, I did go back to Chechnya, only to find myself blockaded in the capital, Grozny. The city was sealed off after a series of strange events. Controls were so tight you couldn’t even move between different districts within the city, let alone make your way out of Grozny on foot. On that day, 17 September, a helicopter carrying a commission headed by Major-General Anatoly Pozdnyakov from the general staff in Moscow was shot down directly over the city. He was engaged in work quite unprecedented for a soldier in Chechnya.

Only an hour before the helicopter was shot down, he told me the task of his commission was to gather data on crimes committed by the military, analyse their findings, put them in some order and submit the information for the president’s consideration. Nothing of the kind had been done before. Their helicopter was shot down almost exactly over the city centre. All the members of the commission perished and, since they were already on their way to Khankala airbase to take a plane back to Moscow, so did all the material they had collected.

That part of the story was published by Novaya Gazeta. Before the 19 September issue was sent to the printers, our chief editor Dmitry Muratov was summoned to the ministry of defence (or so I understand) and asked to explain how on earth such allegations could be made. He gave them an answer, after which the pressure really began. There should be no publication, he was told. Nevertheless, he decided to go ahead, publishing a very truncated version of what I had written.

At that point, the same people at the ministry who had claimed our report was false now conceded it was true. But they began to warn of new threats: they had learned that certain people had run out of patience with my articles. It was, in other words, the same kind of conversation as before my last trip to Chechnya. Then we heard that a particular officer, a Lieutenant Larin, whom I had described in print as a war criminal, was sending letters to the newspaper and similar notes to the ministry. The deaths and torture of several people lie on his conscience and the evidence against him is incontrovertible. Soon there were warnings that I’d better stay at home. Meanwhile, the internal affairs ministry would track down and arrest this self-appointed military hitman, and deputy minister Vasilyev would himself take charge of the operation.

I was supposed to remain at our apartment and go nowhere. But they made no progress in finding Larin, and I began to realise that this was simply another way of forcing me to stop work. The newspaper decided I should leave the country until the editors were sure I could again live a normal life and resume my work.

The paper was forced to omit from my story the sort of detail that is vital to the credibility of an article like this, which suggested the military themselves had downed the helicopter. All my subsequent difficulties began with those details. If these details surface, the ministry of defence warned our chief editor, that’s the end for you . . .

In fact, since I was moving around the city at the time, I can personally testify to what happened, as can others who were there with me. And these were no ordinary citizens: among them were Chechen policemen and Grozny Energy Company employees who, like me, were trapped inside the city. FSB [former KGB] General Platonov was also there. Currently, he is a deputy to Anatoly Chubais, chief executive of United Energy Systems, a key Kremlin player throughout the 1990s and a hawk on Chechnya. All these saw and knew exactly what I know. Platonov is not only Chubais’s deputy but remains a deputy to FSB director Patrushev (in early 2001, the ‘anti- terrorist operation’ in Chechnya was transferred from the military command of the Combined Forces Group to the FSB and its director Patrushevin Moscow placed in overall charge). No one else saw and knew as much about what happened as Platonov — he couldn’t help but see it. Not one person was allowed into the city centre after 9am that morning. And yet a helicopter was downed there.

Different branches of the military are split over future policy in Chechnya. There are good reasons why the recent public statements of defence ministry spokesmen all repeat the same phrases: ‘We deny the possibility of negotiations’; ‘It’s out of the question’; ‘We are just doing our job.’ Indeed they are: their ‘sweep and cleanse’ operations have become even more brutal. Let us suppose that those representing certain other branches of the military on the ground in Chechnya are pursuing a rather different policy. That is where you should seek the reason for the deaths of all the commission members. I’m just a small cog in that machine — someone who happened to be in the thick of events when no other journalists were around.

Those who want to continue fighting seem to have the upper hand; they represent the more powerful section within the so-called CFG, the Combined Forces Group. To avoid repetition of the disastrous lack of coordination between ministries of defence and internal affairs and the FSB during the first Chechen conflict in 1994—96, overall command of army, police and other paramilitary and special units (CFG) in the present war was given to the military. Although the FSB supposedly now exercise overall control of the ‘anti-terrorist operation’, the military are too strong for them. On the fateful day the helicopter was downed and the commission perished, not even servicemen and officers were permitted to enter the central, cordoned-off area of Grozny. Only defence ministry officials were allowed through. Even FSB and ministry of justice people were kept out; that was extraordinary. No one was permitted to enter the area where the helicopter was about to fall: representatives of other military bodies and organisations, even ranking officers, had no right to go there.

I don’t think we should expect too much from the defence ministry, nor from President Putin [in the light of the US-led campaign in Afghanistan. Ed]. He has received carte blanche to take the measures and employ the forces he considers necessary in Chechnya. I’m thinking of Prime Minister Blair’s recent activities and words spoken by Chancellor Schroeder when Putin was visiting Germany. As you know, it was then said that Europe should re-examine its stance on Chechnya.

Their position was already pretty feeble and bore no relation to the real state of affairs in Chechnya and the abuse of human rights there. If, however, they are going t o alter their position, then it’s clear what will happen. I n practical terms they’ll support Putin. Whatever he does will be fine by them. I think he’s been working steadily and persistently towards that end for some time. And I’m sure he’ll make good use of it now. Not for the first time in the present war, there’s been a battle to see whose nerve is stronger. Putin held back [over the West’s ‘anti-terrorist operation’] for some while: we shan’t support the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan, he said, but we’ll offer them back-up. Then he agreed to supply them with arms and, evidently, advisers. In exchange he received a free hand in Chechnya. That’s the way things are likely to go, I’m afraid.

I can’t say when it will happen, but whatever happens there will be a more intensive ‘liquidation of Chechen partisans’. As always in Russia, however, it all depends on the methods to be used. What will the ‘liquidation of Chechen bandits’ amount to this time? Will they herd everyone else into concentration camps or hold repeated sweep operations in all the population centres in Chechnya?

I can’t answer for Chechen President Maskhadov, but will offer a brief analysis of his actions. In my view, he is doing nothing whatsoever. He has retreated into his shell and is thinking, to the exclusion of all else, about his own immediate future — he’s forgotten the Chechen nation. Just as the federal authorities in Moscow have abandoned the Chechens, so now have the other side. The nation has to fend for itself, with no leadership or protection. It survives as best it can. If people need to take revenge for their tortured and murdered relatives, they will. If they need to say nothing, they’ll keep their mouths shut. In such circumstances, which are the equivalent of a civil war, and under continuing pressure from the federal forces, no one today can say whom the Chechen nation would vote for if elections were held. No one now has any idea whom they’d elect and in that respect everyone has committed the same enormous mistake.

Maskhadov has obviously been driven into a corner. But the struggle for independence has become an obsession with him: he will hear of nothing else. I don’t really understand what use independence will be to him, when he, Shamil Basayev and his immediate bodyguard are all that’s left. The first duty of a president is to fight for the well-being of his nation. I have my own president and it makes no difference that I personally did not vote for Putin. He remains the most important figure in the Russian state. And I’d like him to enable me, and everyone else, to live a normal life. I’m referring to the laws that should govern our existence. I find myself in a situation, however, where no one gives a damn how I survive. I’m cut off from my family. I don’t know what will happen in the future to my two children. It is not law that rules Russia today. There’s no person and no organisation to which you can turn and be certain that the laws have any force.

I have no thoughts about my future. And that’s the worst of all. I just want everything to change so I can go back and live in Moscow again. I can’t imagine spending any length of time here. Or in any other place, for that matter. I must do all in my power to return to Moscow. But I have no idea when that will be.

If people in my country have no protection from this lawless regime, that means I survive here while others are dying. Over the last year I’ve been in that position too often. People who were my witnesses and informants in Chechnya have died for that reason, and that reason alone, as soon as I left their homes. If it again proves the case, then how can I go on living abroad while others are dying in my place?

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”78078″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]In the autumn 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Russian journalist Andrey Arkhangelsky reflected on Politkovskaja’s legacy 10 years on, and looks at the state of journalism in the country today. You can get your copy here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Copies will be available at the BFI, the Serpentine Gallery, MagCulture, (London), News from Nowhere (Liverpool), Home (Manchester), Red Line Books (Colchester) and on Amazon. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship continue its fight for free expression worldwide.

The full contents page of the magazine can be read here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1535620669542-cd67c3af-4d46-5″ taxonomies=”1305″][/vc_column][/vc_row]