6 May 2016 | Belarus, Europe and Central Asia, Macedonia, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Russia, Turkey, Ukraine

April 2016 was the busiest month for Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom since the project began in May 2014, with a total of 87 violations against the media recorded. While MMF records violations from over 40 countries, the majority (55%) of last month’s violations came from just five countries.

These hotspots for attacks on the media will come as no surprise to anyone following the project in recent months.

Turkey continues to be the worst offender

With 16 violations recorded within its borders in April, Turkey is again the location with the most offences.

One of the most worrying occurrences last month was on 28 April when journalists Ceyda Karan and Hikment Chetinkaya, who work for Turkish daily Cumhuriyet, were sentenced to two years in prison for publishing the cover of Charlie Hebdo magazine featuring an image of prophet Muhammad. The pair were convicted of inciting “hatred and enmity”.

In another instance, on 30 April, Hamza Aktan, news director of private Istanbul-based IMC TV, was arrested by anti-terror police. Aktan was escorted to the police station where he was interrogated for 12 hours and then released. The editor is being accused of spreading propaganda for a terrorist organisation and trying to build public opinion abroad against interests of Turkey for four public tweets.

UPDATE: Government-seized Zaman and Cihan forced to close

Index on Censorship’s latest quarterly report includes a case study on an Istanbul court appointing a group of trustees to take over the management of Zaman newspaper. Since the report, it has been announced that Zaman and Cihan News Agency, also government-seized,

are to be permanently closed on 15 May. The decision comes the day after the European Commission recommendation of granting Turkey visa-free travel to the EU.

Russia: Big business throws its weight around

As the Panama Papers showed in April, investigative journalism is essential if misconduct and abuse by big business are to come to light. This makes a recent trend in Russia all the more worrying.

A total of 12 reports were filed in Russia last month, three of which related to journalists investigating business. On 12 April, when covering truckers protesting against the “illegal” actions of Omega, journalist Anton Siliverstov’s phone was stolen by Evgeni Rutkovski the director of the transport company. When he asked Rutkovski to comment on the protest, Siliverstov was forced from the office. The journalist said he would record the incident on his phone, at which point Rutkovski snatched the journalist’s device, refused to give it back and called security. Siliverstov hasn’t seen the phone since.

Two days later, reporter Igor Dovidovich was assaulted by the head of Gaz-Service, a gas company he was investigating. His TV crew was also attacked by the firm’s employees.

The month ened with state oil company Rosneft filing a judicial complaint against BiznessPress for an article which, the firm said, is “false and represents baseless fantasies of journalists or their so-called sources”.

Ukraine: TV journalists in the firing line

Ukraine continues to be unsafe for many media workers, with nine reports submitted to the project in April. Violations included five cases of intimidation, two attacks to property and several physical assaults. On 1 April, unidentified assailants set a local TV studio on fire with molotov cocktails. Studio equipment and furniture were destroyed. No one was injured.

Three days later, claims emerged that journalists working for TV channel 1+1 were under surveillance, have received death threats and have been assaulted. Later in the month, journalists from the station were attacked on 19 and 20 April.

Belarus: Journalism as a crime

Journalism is not a crime, but you’d be excused for thinking otherwise when observing recent events in Belarus. Seven reports were filed for Belarus last month, including two criminal charges resulting in fines, three arrests, and one journalist interrogated for doing his job.

On 15 April, freelance journalists were fined approximately €330 each for contributing to Polish TV channel. Kastus Zhukousky and Larysa Schyrakova were found guilty of illegal production and distribution of media products and for contributing to a foreign media outlet without accreditation.

Zhukouski has been fined seven times this year alone.

Macedonia: Anti-government protests turn sour

Six reports were submitted from Macedonia during April. The most worrying instances involved attacks to property (2) and a physical assault, leading to an injury.

April saw a wave of anti-government protests with thousands marching, mainly peacefully, through the capital city of Skopje. On 13 April four photographers and one journalist were injured by police during the anti-government demonstration. Two TV journalists were also injured by demonstrators on the day. On 14 April the offices of the Slobodna Makedonija radio station were pelted with stones by some anti-government demonstrators, causing the windows to break and other material damages.

Mapping Media Freedom Quarterly Report

Index on Censorship has released its report for the first quarter of 2016 covering 1 January and 31 March 2016. During this time: Four journalists were killed; 43 incidents of physical assault were confirmed; and there were 87 verified reports of intimidation, which includes psychological abuse, sexual harassment, trolling/cyberbullying and defamation. Media professionals were detained in 27 incidents; 37 criminal charges and civil lawsuits were filed; and media professionals were blocked from covering a story in 62 verified incidents.

“Conflict in Turkey and eastern Ukraine along with the misuse of a broad range of legislation — from limiting public broadcasters to prosecuting journalists as terrorists — have had a negative effect on press freedom across the continent,” Hannah Machlin, Mapping Media Freedom project officer, said.

24 Mar 2016 | About Index, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are just five reports from 15-22 March that give us cause for concern.

Serbia: B92 journalists receive several death threats

Several death threats have been sent to journalists at the investigative journalism portal insajder.net which is owned by broadcaster B92. The threats were sent via email to several reporters between 14 and 22 March.

Insajder’s editor-in-chief Brankica Stankovic and B92’s editor-in-chief Veran Matic have also received threats. Both have been under police protection for years due to severe threats.

Interior Minister Nebojsa Stefanovic announced on 23 March that a person had been arrested for threatening Stankovic and Matic. Due to a pending police investigation no details of the threats have been revealed, Veran Matic told Index on Censorship.

Kosovo: Investigative journalist claims prime minister threatened him

Isa Mustafa, European People’s Party Summit, March 2015, Brussels. Credit: Flickr / EPP

Vehbi Kajtaz, a journalist for the investigative reporting portal insajderi.com claims he received a threatening phone call from Kosovo’s prime minister, Isa Mustafa, on 20 March.

Kajtazi had published an in which he criticised Kosovo’s healthcare system, stating it is so poor that even Mustafa’s brother has to seek asylum in the EU for treatment for his throat cancer. Mustafa has denied threatening the journalist.

On 21 March, Kajtaz wrote on his Facebook page that Mustafa had called him on his mobile phone on the day previous. Kajtazi claims that Mustafa was angry about an article mentioning his brother and said that the journalist would “pay heavily”.

Serbia: Investigative portal claims to be monitored by pro-government tabloid

The Serbian Crime and Corruption Reporting Network (KRIK) has condemned the “lynch campaign” against it by Informer, a Serbian pro-government tabloid. KRIK claims Informer has been following its editor-in-chief Stevan Dojcinovic, monitoring its work and putting his life at risk.

On 18 March, Informer published a photo of Dojcinovic on the front page with an article stating that KRIK is working with “drug dealers, criminals, corrupt cops, but also agents of some of the foreign intelligence services” in order to force prime minister Aleksandar Vucic to give up his position.

“Besides the fact that KRIK’s editor was followed and photographed on the street, we are most concerned about the details presented in the article about specifics of our current journalistic research on the assets of politicians,” Jelena Vasic from KRIK told Index on Censorship. “This raises a serious question about who is monitoring KRIK and how they know the details of our unpublished stories.”

Russia: Local editor and deputy knifed by two assailants

Two unidentified individuals attacked Igor Rudnikov, the founder and editor of the newspaper Novaye kolyosa and deputy of the Kaliningrad district parliament, on 17 March. The attack took place at a café in the city centre where Rudnikov often frequents.

The assailants reportedly waited for him outside the café and when the editor left, they slashed him with a knife. Rudnikov was taken to hospital where he was operated on. The editor’s contacts claim the attack is related to his journalism activities.

He has published a number of articles on crime and corruption in the Kaliningrad region. He was previously assaulted in 1998 when he was Rudnikov was severely beaten in the entrance to his home.

Macedonia: Constitutional court ban journalists from session

The constitutional court in Macedonia announced on 16 March that a session on whether the president will regain the right to pardon persons convicted of electoral fraud would be closed to journalists and the public.

A heavy police presence kept protesters and critics 100 metres away from the court building, while a group of government supporters had set up camp protesting “in defence of the judges”. In a statement, the Association of Journalists in Macedoni (ZNM) and condemned the decision to hold such an important session behind closed doors and have.

Until 2009, the president had right to pardon people accused of convicted of electoral fraud. The court has now ruled that the president can pardon alleged election-riggers.

12 Feb 2016 | mobile, News, Youth Board

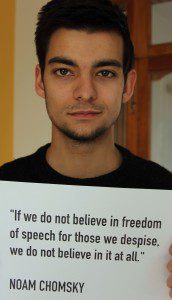

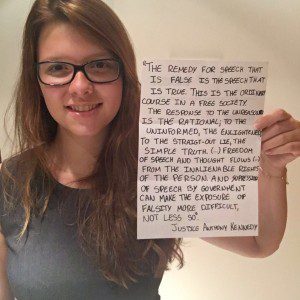

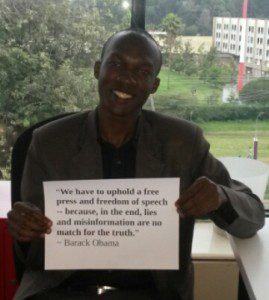

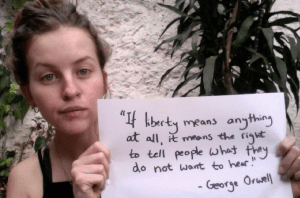

Index on Censorship recently appointed a new youth advisory board who attend monthly online meetings to discuss current freedom of expression issues and complete related tasks. As their first assignments they were asked to provide a short bio to introduce themselves, along with a photograph of them holding a quotation highlighting what free expression means to them.

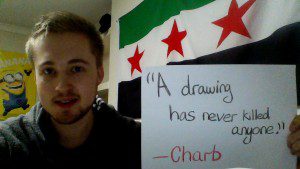

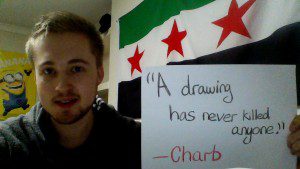

Simon Engelkes

I am from Berlin, Germany, where I study political science at Free University Berlin. I have worked as an intern with Reporters Without Borders and RTL Television, which made me passionate about the importance of freedom of speech.

I believe that freedom of expression forms an important cornerstone of any effective democracy. Journalists and bloggers must live without fear and without interference from state or economic interests. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Journalists, authors and everyday citizens are imprisoned or killed by radicals, state agencies or drug cartels. Raif Badawi, James Foley, Khadija Ismayilova, Avijit Roy – the list is endless.

We need to remind ourselves and the powerful of today, that freedom of expression as well as freedom of information are basic human rights, which we have to defend at all costs.

Mariana Cunha e Melo

Mariana Cunha e Melo

I am from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. I graduated from law school in Rio and I have a degree from New York University School of Law. My family has taught me about the dangers of censorship and dictatorship, so I have always been interested in studying civil rights. This was the main reason I decided to study law.

I grew up listening to stories about the media censorship in Brazil during the military dictatorship. The fight against the ghost of state censorship has always sounded very natural to me – and, I believe, to all my generation. When I finished law school I found out that the new villain my generation has to face is the censorship based on constitutional values. The argument has changed, but the censorship is not all that different. So I decided to dedicate my academic and my professional life as a lawyer to fight all sorts of institutionalised censorship in Brazil.

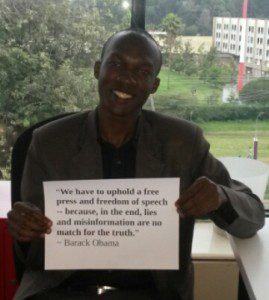

Ephraim Kenyanito

Ephraim Kenyanito

I was born and raised in Kenya, and I am currently working as the sub-Saharan Africa policy analyst at Access Now, an international organisation that defends and extends the digital rights of users at risk around the world. My role involves working on the connection between internet policy and human rights in African Union member countries. I am an affiliate at the Internet Policy Observatory (IPO) at the Center for Global Communication Studies, University of Pennsylvania. I also currently serve as a member of the UN Secretary General’s Multi-stakeholder Advisory Group on internet governance.

The reason why I have always been passionate about protecting the open internet is that it is a cornerstone for advancing free speech in the post-millennium era and there is a great need to build common ground around a public interest-oriented approach to internet governance.

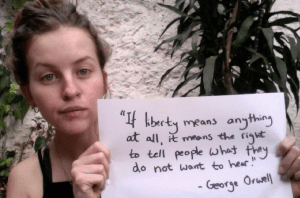

Emily Wright

I grew up in Portugal, and I am now based between London and Bogotá, Colombia. I am a freelance filmmaker and journalist. Working in documentary production and community-based, participatory journalism informed a growing interest in journalistic practices, freedom of expression and access to information.

I believe that one of the greatest threats to freedom of expression is the flagrant violation of civil liberties under the banner of national security. The war on terror, underscored by Bush’s declaration “You’re either for us or against us”, has collapsed the middle ground, suppressing any struggles that challenge that statement. Freedom of expression has become a pretext for silencing those who have the least access to it; those who do not fall in line with the global order’s supposed defence of freedom against barbarism and obscurantism.

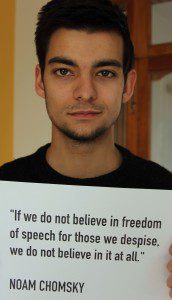

Mark Crawford

Mark Crawford

I’m originally from Birmingham, and now a postgraduate student at University College London, specialising in Russian and post-Soviet politics. This has inevitably educated me on the pressures exerted upon freedom of expression in Russia, whose suffocated and disenfranchised opposition journalists I am currently investigating.

Hostility to free expression has become a staple of my university life. Rather than developing a coherent set of ideologies to challenge toxic values in the open, it has become mainstream for students of the most privileged universities in the world to veto them on behalf of everyone else, no-platforming and deriding free speech.

I am convinced that there is no point fighting for an egalitarian society if any monopolies over truth are permitted. Freedom of speech is, therefore, something I am keen to promote in whatever small way I can.

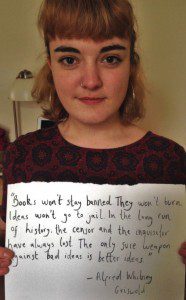

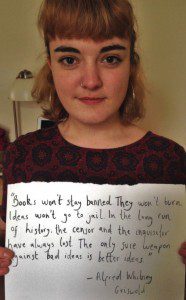

Madeleine Stone

My home is in south-east London but I spend most of my time in York, studying for my bachelor’s degree in English and related literature. I am currently the co-chair of York PEN, the University of York’s branch of English PEN, and a founding member of the Antione Collective, a human rights-focused theatre company.

Studying literature from across the globe has introduced me to issues of freedom and censorship, and the devastating effects censorship can have on national progress. Freedom of expression on campuses is hugely important to me as a student and it is currently under threat. Well-meaning individuals are shutting down the open debate that is vital to academic institutions. The only way to fight harmful ideas is to engage them head-on and destroy them through academic debate, not to ban them.

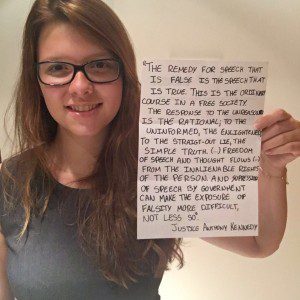

Layli Foroudi

I am a journalist and student currently studying for a MPhil in race, ethnicity and conflict at Trinity College Dublin. It was studying literary works from the Soviet period during my undergraduate degree in Russian and French at University College London that initially highlighted the issue of censorship for me. The quote I selected, “manuscripts don’t burn”, is from the book Master and Margarita by Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov. He wrote about the hardship that many writers faced as they had to adjust their own writing in accordance with the authority, as well as the fact that not all that is written can be taken to be true.

I think that these themes are very relevant today. Whether people are censored or self-censor out of fear of punishment or of being wrong, limiting freedom of expression results in loss of debate, of exchange and of creativity. Being denied freedom of expression is being denied the right to participation in society.

Ian Morse

Ian Morse

I have been involved in journalism since I began studying at Lafayette College, Pennsylvania, USA, and have been engaged in press freedom and reporting in three countries since then. I studied in Turkey last spring, where I interviewed and wrote about journalists and press freedom. It motivated me to begin researching and writing on my own about these topics. Now, as I study for a semester in Cambridge in the UK, I continue to talk about and advocate for free speech and press.

I find it absolutely amazing the power words and information can have in a society. It becomes then extremely damaging to realise that some things cannot be published because they conflict with those in power. Free speech is now becoming a hot topic around the world, particularly among youth, and it makes it all the more important to be able to approach freedom of expression critically and objectively.

28 Jan 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, News, Russia

(Image: /Demotix)

Russia’s media freedom has declined under the government of Vladimir Putin. The president and his allies have used a cloak of legislative legitimacy to target potential opposition to his rule. Mapping Media Freedom correspondents Ekaterina Buchneva and Andrey Kalikh explore what this means for two important sectors of the Russian media.

Print and broadcast media

By Ekaterina Buchneva, Mapping Media Correspondent

Under Russia’s law on mass media amended in autumn 2014, foreign owners are restricted to 20% of shares in media organisations in the country. Its authors said that the legislation would halt the West’s “cold information war”. The law has triggered major changes in the Russian media market and, as critics warned when the law was passed, was used to replace international investors with locals loyal to the Kremlin.

The Russian edition of Forbes magazine, formerly owned by German media conglomerate Axel Springer and known for its independent editorial policy, was sold to businessman Alexey Fedotov, who immediately said that the publication was “too focused on politics” and should cover more business news. In January 2016, the magazine named Nikolay Uskov as its new editor-in-chief. Uslov, a former editor-in-chief of the Russian edition of GQ, has never worked in business journalism.

Finland’s Sonoma Independent Media, America’s Dow Jones and the UK’s Pearson also had to sell their shares in Vedomosti, the main business newspaper known for its critical opinion pieces. Now the paper’s new — and only — owner is Demian Kudryavtsev, a business partner of oligarch Boris Berezovsky, who died in 2013, and a former chief executive of major Russian publishing house Kommersant. Kudryavtsev also purchased The Moscow Times, the country’s only English-language daily. Some journalists were concerned about the origin of the money Kudryavtsev used in the deal and suggested that there was another buyer behind him.

The media ownership law also affected a number of glossy magazines, which, as one of the law’s author said, “squeeze articles favorable to the West and the fifth column in between news about cars and glamorous watches”, and entertainment television channels. CTC Media sold 75% of its shares to loyal to the Kremlin oligarch Alisher Usmanov, who also owns the Kommersant publishing house.

The Russian broadcasters of CNN, Cartoon Network and Boomerang, as well as 11 television channels of Discovery group, came under the control of Media Alliance, 80% of which belongs to National Media Group. The president of NMG, which also owns a number of Russian media organisations, including RenTV, Channel Five, Izvestia newspaper and 25% of Сhannel One, is Kirill Kovalchuk, a nephew of Putin’s old friend Yuri Kovalchuk.

Tightening control over foreign publishers

In addition, in December 2015, another bill with new amendments to the “law about mass media” was introduced into the Russian State Duma. It contains more limitations for media organisations, some of them refer to foreign publishers.

The bill suggests new legal background — violation of anti-extremism legislation — for denying or revoking distribution permit for foreign publishers. Among the ones that now have such permits are Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, China Daily, European Weekly, GQ, Cosmopolitan, Esquire, Tatler, Vogue, and some papers from CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) countries, including Expert.Ukraine magazine.

“The problem is vagueness and inconsistency of the anti-extremism legislation itself and the practice of its implementation by the Russian authorities,” says Damir Gainutdinov, lawyer of Inter-regional Association of Human Rights Organisations “Agora”.

“It is primarily about Article 1 of the Federal Law on Countering Extremist Activity, which gives a definition of extremism, extremist materials, etc. In practice, this definition is used not only for hate crimes but also, for example, criticism of the Russian authorities. Condemnation of the Crimea annexation is recognised as calls for infringement of the territorial integrity of Russia, as it was in the case of Rafis Kashapov (Tatar activist from Tatarstan, who was convinced in September 2015 to three years in jail for posting informational materials criticising Crimea annexation), and criticism of the United Russia is recognised as the incitement of hatred to a social group, as it was in the case of prohibition of video clips by Navalny (a few activists were found guilty of distribution of extremist materials for posting a video by opposition leader Alexey Navalny titled ‘Let’s recall manifest-2002 to crooks and thieves’, on social media). Therefore, any unenthusiastic article published by foreign media may be recognised as a violation of anti-extremist legislation. Another thing is that this applies only to the print media. Since February 2014, it works much easier with websites; they can be just blocked by orders of the general prosecutor office.”

According to the bill, the foreign publishers also will have to pay a fee for issuing a distribution permit. The authors explained that it would “eliminate the unfair advantage of the founders of foreign publications that provides them with more favorable business conditions”.

Another bill, that was already approved by the State Duma, requires Russian media organisations to inform Roskomnadzor (The Federal Service for Supervision in the Sphere of Telecom, Information Technologies and Mass Communications) about foreign funding, including funding from foreign states, international organisations and Russian NGOs that were considered “foreign agents”. The minimum amount of money that should be declared is 15,000 roubles (less than $200). Penalties for not notifying Roskomnadzor will be fines of 30-50,000 roubles (about $400-600) for officials and the amount of money received for companies. A repeated violation will be punished with a fine of 80,000 roubles (about $1,000) and triples amount of money received.

This bill resembles the one adopted in June 2012 by the Russian State Duma, requiring NGOs to register as “foreign agents”, says Damir Gainutdinov. “First, it is a simple registration and then more and more new burdens will be introduced, for example, state bodies will deny accreditation of such media organisations, officials will be banned from giving them interviews and answering their questions … An additional mandatory audit and special checks of staff could be introduced, who knows what else.”

The bill about foreign funding could affect a number of media platforms – from Colta.ru that cover art and culture to Mediazonа that highlights problems of the Russian justice and the penal system.

Limitations for founders of media organisations

Another block of amendments introduces a new restriction for media founders. It suggests that those, who have unspent or unexpunged convictions for crimes against the constitutional order, public security and public safety, can not found a media organisation.

Those crimes include a number of criminal articles – from hooliganism and repeated violation of rules of organising or holding rallies and demonstrations to espionage and treason. But the most tricky ones are incitement of hatred and abasement of human dignity (Article 282 of the Criminal Code of Russia), public calls for extremism (Article 280) and public calls for infringement of the territorial integrity of Russia (Article 280.1), says Damir Gainutdinov. “These articles are used for persecution of dissenters. In absolute numbers, there are not many cases like this against journalists, but such practice is developing gradually – Stomaknih, Yushkov, Kashapov”.

However, these limitations could not prevent dissenters from taking part in media management at different positions. For example, Pussy Riot members Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alekhina, who were convinced for hooliganism, founded Mediazona platform, but as Tolokonnikova told RBC newspaper, they were not officially registered as founders as they had foreseen possible legal problems.

Internet

By Andrey Kalikh, Mapping Media Correspondent

Russia’s environment for freedom of expression on the internet has declined precipitously since 2002 when the law on Counteracting Extremism was adopted. The definition of extremism used in the law is vague and overly broad, according to Aleksandr Verkhovski, an expert on extremism from the SOVA Information and Analytical Centre in Moscow. Verkhovski said that the law was written to keep independent media, oppositional political parties, and “not official” religious confessions under control.

In 2012, the anti-extremism law was amended to empower Roskomnadzor, the state media and communication watchdog, to launch the United Register of Banned Websites. The modifications also enabled the agency to add websites that have “extremist content” without judicial approval. Once a site is added to the list, Russia’s internet services providers are obliged to block it. Within days of the changes, several independent media outlets and political opposition sites websites and blogs — Grani.ru, Ej.ru, Alexei Navalny’s blog — were blacklisted in the country.

On 30 December 2015 a district court in the Siberian city of Tomsk sentenced blogger Vadim Tyumentsev to five years in prison for two videos he posted on his YouTube page.

In the first video, the blogger criticised the local government’s decision to raise the cost of fares on the city’s public transport. In the second video, he said that authorities help refugees from eastern Ukraine more than they help local residents.

The court recognised both of Tyumentcev’s videos as “having extremist character”. Ekaterina Galyautdinova, the presiding judge, gave Tyumentsev a sentence even longer than the prosecutor had pursued. She also banned Tyumentsev from posting online for three years.

The Tyumentcev case is far from the first time that a blogger has been subjected to a prosecution. In 2007, Savva Terentyev, a blogger from the Siberian city of Syktyvkar, was sentenced to a large fine for “offending a social group” – in this case, the local police force – by writing about bad behaviour and human rights abuses committed by officers. In 2012, Maxim Efimov, a blogger from Petrozavodsk, Republic of Karelia, faced prosecution after he posted an article under the headline.

In 2012, Maxim Efimov, a blogger from Petrozavodsk, Republic of Karelia, faced prosecution after he posted an article under the headline “Karelia is tired of priests”, in which he criticised the leadership of the Russian Orthodox Church. Efimov left Russia and was subsequently granted political asylum in Estonia.

That same year the Prosecutor General Office blocked the website and blog of Alexei Navalny, blogger and opposition leader, for allegedly calling “for mass disorders”. Navalny was sentenced to the administrative detention for 15 days and faced other accusations related to his political activities.

“Bloggers law”

In August 2014, the Russian State Duma adopted a number of amendments to communication legislation. The so-called “bloggers law” required sites with more than 3,000 visitors a day to register with Roskomnadzor and observe the same rules as much larger media outlets.

Under the amendments, all site owners and social media users are required to disclose their names and email address on their websites. Owners and users must keep all the information published on the web including personal data for at least six months and immediately submit to the law enforcement bodies on demand.

Moreover, Roskomnadzor received the right to request personal information from all site owners and users.

Most recently, as of 1 January 2016, the “bloggers law” requires all websites and social media platforms to keep all personal data of Russian users on servers within Russian territory. Failing to do this means Roskomnadzor can block the site or service. Companies can either comply or cease doing business in Russia.

According to the Roskomnadzor spokesman Vladimir Ampelonski, some foreign companies submitted to the requirement and brought their servers to Russia. However, some companies — Google, Facebook and Apple — have defied implementing this change. Facebook representatives met with the authority’s deputy chief, Aleksandr Zharov. At the meeting the company said it will not observe the law because it is “economically disadvantageous”, the Vedomosti newspaper reported.

Empowering the FSB

After Putin’s re-election in 2012, Russian security service FSB’s powers were considerably expanded. Articles of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation on high treason, espionage and disclosure of state secrets were widened and made ever more vague by introducing language on cooperation with any “foreign organisation, or their representatives in hostile activities to the detriment of the external security of the Russian Federation”.

The FSB has further tried to make investigative journalism more by lobbying members of the State Duma to pass a draft law limiting access to information on commercial real estate transactions. If passed, the law would make it impossible to uncover cases of illicit enrichment by government officials.

This article was originally published on Index on Censorship.

Mariana Cunha e Melo

Mariana Cunha e Melo  Ephraim Kenyanito

Ephraim Kenyanito

Mark Crawford

Mark Crawford

Ian Morse

Ian Morse