22 Dec 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia, Turkey

Before 24 November, Turkey was described in Russian news reports as a reliable partner in ambitious projects (TurkStream pipeline, construction of Sochi’s Olympic venues), a source of fruits and vegetables in a period of European food embargoes and Crimea blockade, and one of the main tourist destinations, visited annually by over three million Russians.

But after the downing of the Russian fighter jet, Turkey became the target of a new information war. Reports on estimated growth of turnover and perks at Turkish resorts in Russian state-run media were replaced by a long list of accusations.

Dmitry Kiselev, the head of a state international news agency Rossiya Segodnya and the anchorperson of a weekly programme Vesti Nedeli accused Turkey of buying oil from the Islamic State, exporting carcinogenic vegetables to Russia and trying to revive the Ottoman Empire. Vladimir Soloviev, a popular anchorperson on television channel Rossiya 1, labeled Turkey a sponsor of terrorism.

All media platforms, directly or indirectly controlled by the state, were used in the construction of an image of a new enemy. The past was revised by articles, recalling a long history of Russian-Turkish wars and crimes of the Ottoman Empire. The future was programmed by analysing chances in a possible third world war. Coverage of current affairs has become far from unbiased. News selection has been focused on demonstration of Russia’s sanctions effects and Turkey’s internal problems — oppression of journalists, a growth of child marriage and crime.

After weeks under information attack, on 3 December, Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu dismissed the allegations by Russian media as “lies of this Soviet-style propaganda machine”.

“In the Cold War period, there was a Soviet propaganda machine. Every day it created different lies. Firstly, they would believe them and then expect the world to believe them. These were remembered as Pravda lies and nonsense,” he said.

Days later the Russian state news agency RIA Novosti proved his point by using a classic Soviet propaganda trick. In an op-ed that called Davutoglu “Reich Minister”, RIA Novosti compared the new enemy to the old by appealing to one of the most loathed images for all Russian people since the WWII – Nazi Germany.

This method, as with many others used against Turkey, has been tested and mastered during the Ukrainian crisis. Maidan activists, who later became a new elite of the country, were also labeled by Russian television channels as “fascist nationalists” and “extremists”. The technology of information war, the main propaganda mouthpieces and the image of the enemy remain the same.

On 7 December, Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VTsIOM) published the results of its survey, saying that 73% of Russian population have changed their attitude to Turkey to the worse since the downing of Su-24.

VTsiom, whose director admitted that the main clients of the center are the Kremlin and the ruling party United Russia, has been criticised for manipulation. The results of the survey are symptomatic. If the data is correct, it demonstrates that anti-Turkey propaganda works very well. If the results were rigged in favour of the Kremlin’s agenda, it shows the desirable goal of the information attack.

The day after, on 8 December, a film crew from Russia’s state television channel Rossiya 1 was detained in the Turkish province of Hatay, close to the Syrian border, and deported from the country because of “violations of regulations of work of foreign journalists in the Turkish Republic”. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation responded with harsh critiques, accusing Turkey of “a series of infringements of the rights of local and foreign journalists”.

However, in a communique by OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media on propaganda in times of conflicts, published last year in reference to a similar case related to the Ukrainian crisis, Dunja Mijatović made it clear that censoring propaganda is not the way to counter it. The best way to neutralise propaganda is balance and accuracy in broadcasting, independence of media regulators, prominence of public service broadcasting with a special mission to include all viewpoints, a clear distinction between fact and opinion in journalism and transparency of media ownership.

A similar view was expressed in a speech by Agnès Callamard, the former executive director of ARTICLE 19, delivered at UN Headquarters in December 2014.

“Hatred needs and is fed by censorship, which, in turn, is needed to nurture incitement to the actual commission of atrocity crimes. The lesson is clear: In our efforts to prevent mass atrocities, the free flow of information and freedom of expression are ultimately are our key allies – not our enemies.”

7 Dec 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia

Russia’s takeover of Crimea has been accompanied by an ongoing process that is shrinking the space for media and freedom of speech on the peninsula. As the clampdown progressed, a majority of the independent journalists either left the disputed territory or stopped openly criticising Russian policy. At the same time, the number of alternative sources of information declined significantly.

Russian and Crimean authorities have used red tape, paramilitary violence and threats to silence independent voices and media. They have stifled freedom of information and jeopardised journalist safety.

Journalists and media professionals dubbed Crimea “fear peninsula”.

Curtailing broadcast TV

As Russia took over, television stations opposed to the annexation were one of the first targets. In March 2014, Chornomorska, the largest local TV and radio company, and all Ukrainian stations had their analogue broadcasts terminated. This was followed two months later, in June 2014, by the dropping of Ukrainian cable TV channels in some cable networks.

Applying Russia’s extremism law in Crimea

Soon after the annexation, Russia began implementing its overly broad and vague 2002 law, On Countering Extremist Activity, which led to a surge in warnings against the media. In summer 2014, Shevket Kaybullaev, the editor-in-chief of the Crimean Tatar newspaper Avdet , was summoned to the office of public prosecution in Simferopol. Kaybullaev was interrogated because of a complaint against the paper that challenged coverage of the mood of the Tatar community in the run-up to local elections. The complainant accused the paper of “radicalism and extremism”.

Verbal accusations against journalists have also become day-to-day practice. The Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) and prosecutor’s offices demanded the removal of “extremist materials” from media outlets. Crimean Tatar TV channel ATR received two warnings about the “violation of legislation aimed at countering extremist activity”. The station management was reminded that the formation of an anti-Russian public opinion could be considered a violation of the extremist law.

Criminal penalties for “incitement to separatism”

On 9 May 2014, amendments were made to Russia’s Criminal Code. A new article, 280.1, states that “public calls for action aimed at violating the territorial integrity of the Russian Federation” is punishable by up to five years imprisonment. The words “annexation” and “occupation” are de facto banned in Crimea when referring to recent events.

The amended code has been used to target Crimean journalists. In March 2015, two journalists, the Center for Investigative Journalism’s Anna Andrievska and Natalia Kokorina, had their apartments searched. Kokorina was interrogated for six hours. The FSB opened the criminal case against Andrievska on charges of “incitement to separatism” based on her reporting on individuals providing support for the Crimea volunteer battalion fighting in Donbas, in eastern Ukraine.

Searches and seizure of property

Russian authorities are using searches and property seizure as a way to intimidate and pressurise media companies. In August 2014, the work of Chornomorska TV and Radio Company and the Center for Investigative Journalism were blocked after the seizure of their broadcasting equipment. The broadcaster wasn’t able to retrieve its equipment until five months later.

In September 2014, a search was conducted at the office of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People, a representative body for the ethnic group. Because it shares the building with the Mejlis, the offices of the Avdet newspaper were also raided. Following the probe, the paper was ordered to vacate its offices within 24 hours.

In January 2015, a search was carried out at the ATR TV channel, which disrupted the station’s broadcasts and prevented newsroom staffers from reporting.

Using paramilitaries to put pressure on journalists

Paramilitary groups have also been used to target journalists. So-called Crimean self-defense groups have been found to have illegally detained, assaulted and tortured journalists, as well as confiscations of and damage to property. From 15 to 19 May, 2014, ten cases of journalists’ rights violations were recorded and documented by the Crimea Field Mission on Human Rights. The situation has been worsened by the fact that to date not all the documented attacks on journalists by self-defense group members have been investigated by Crimean authorities. This has created an atmosphere of fear and impunity.

Problems with registration and re-registration of Crimean media

After the Russian annexation, Crimean authorities demanded that all active media outlets re-register according to Russian legislation. As a result, mass media that was considered disloyal — including News Agency QHA and TV Channel ATR, among others — did not receive legal permission to continue their work on the peninsula. In February 2015, all Crimean independent radio companies were silenced after losing their frequencies during a bidding process that was carried out opaquely. Beginning on 1 April 2015, the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technologies and Mass Communications (Roskomnadzor) stopped recognising Crimean media outlets with Ukrainian registrations, making their work in the annexed territory illegal.

Making media accreditation more difficult

New rules for accreditation in Crimea make it possible to selectively restrict media access to the authorities. The State Council of the Republic of Crimea issued new regulations that make “biased coverage” one of the reasons journalists could lose accreditation. Kerch City Council, for instance, prohibits journalists without accreditation from even entering the city hall.

Blocking access to the online media

In October 2015, media freedom in Crimea came under renewed pressure when websites were blocked. Roskomnadzor carried out a request by the general prosecutor to restrict access to the Center for Investigative Journalism and Events Crimea websites in Crimea and Russia. Roskomnadzor said that the information on the sites “contains calls for riots, realisation of extremist activity and/or participation in mass (public) events held in violation of the established order”.

These internet media outlets became the first Crimean mass media whose content are officially blocked on the territory of Crimean peninsula.

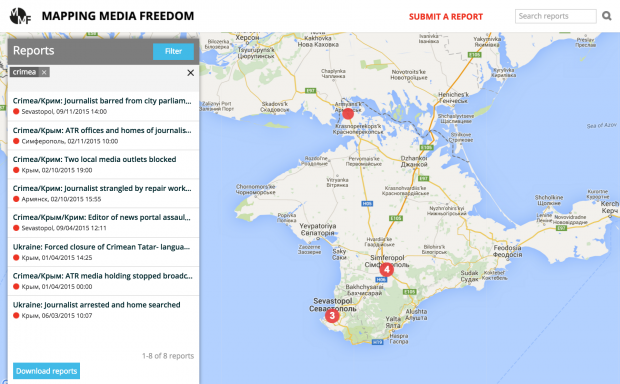

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

20 Nov 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia

The Russian Ministry of Justice has added Glasnost Defence Foundation (GDF) to the list of NGOs it considers foreign agents. The decision was made after an “unplanned inspection”, Radio Liberty reports.

GDF, founded in 1991, is one of Russia’s oldest human rights organisations protecting freedom of the media. It provides Russian journalists with legal information and support. It also monitors media freedom abuses. GDF is the founder of the Andrey Sakharov journalist prize, Journalism As A Deed. The organisation has been headed by a well-known human rights defender, filmmaker and critic, Alexei Simonov.

GDF is not the first Russian journalist and media NGO unwillingly recognised as a foreign agent. At the beginning of 2015, another media freedom NGO, the Centre For The Protection Of Media Rights, was added to the list. In October 2015, Sobytie, a photoclub, became the 100th organisation on the list of foreign agents.

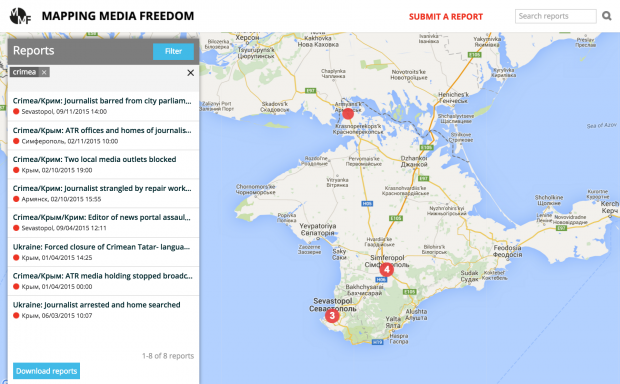

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

13 Nov 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, Russia

Archangel on the roof of St. Isaac’s Cathedral, St.Petersburg, Russia. Credit: Akimov Igor / Shutterstock

Since the amended blasphemy law came into force in July 2013, Russian journalists have faced a growth of religious censorship. This is according to a new study by Zdravomyslie, a foundation that promotes secularism.

Insulting religious beliefs of citizens was previously regulated by the Code of Administrative Offences and punishable by a fine not exceeding 1 thousand roubles (around $15). But after the scandal of the punk-prayer of feminist group Pussy Riot, who were sentenced to two years in jail for a performance in the Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in 2012, the Russian parliament adopted amendments that criminalised blasphemy.

Since July 2013, “public actions, clearly defying the society and committed with the express purpose of insulting religious beliefs” has been declared a federal crime and is punishable by up to three years in jail.

Evgeniy Onegin, a Zdravomyslie researcher, said that the imprecise wording of the law and stricter punishments have affected media freedom and resulted in a growth of self-censorship among journalists. His report Limitation of Media Freedom as a Consequence of the Law About Protection of Feeling of Believers was presented at a conference in Moscow at the end of October.

Onegin interviewed 128 employees of dozens of media organizations, including a major national television channel, radio stations, newspapers and websites. The majority, 119, said that after the revised blasphemy law came into force, managers told them not to mention religions, religious problems, traditions and “different manifestations of unbelief”. Some media organisations even prohibited usage of words “God”, “Allah” and “atheist” in headlines.

A journalist at a sports news website told the researcher that censorship had extended to idioms. For example, headlines “Hulk has talent from God” (about a Brazilian forward playing for Zenit Saint Petersburg football club) and “God’s hand helped Maradona” (about the score of the Argentinian forward at the World Cup in Mexico in 1986) were corrected to exclude the word “God”. The second headline was corrected a long time after publication because editorial staff decided to check archived articles.

Media professionals involved in a production of entertaining content also faced censorship. For example, a respondent working for a sketch show told Onegin about a ban on jokes containing phrases like “God will forgive you” or “you are definitely descended from a monkey”.

However, exceptions to the general policy of avoiding religious issues were made for Orthodox Church, which was confirmed by over the half of all respondents. For example, a journalist working for a national television channel said that her colleagues were told not to show “non-traditional for Russia religious symbols and signs”. However, the term non-traditional was not specified, so journalists started to avoid showing any religious objects, except those associated with the Orthodox Christianity.

The authors of the report presented a list of the most undesirable topics, which according to the respondents are potentially violations of the law. First place went to protest actions against the Orthodox Church (according to 84% of respondents), the second was atheism and unbelief (49%) and third place was coverage of religious events (23%).

Journalists also gave Onegin examples of when they were told not to cover stories: cancellation of celebration of Labour Day because of a coincidence with the holy week of Orthodox Lent; cancellation of performances of the Cannibal Corpse rock group due protests by Orthodox activists; protests of Orthodox activists against Leviathan, a movie by Andrey Zvyagentsev; cancellation of an Lord of the Rings-related Eye of Sauron installation on a Moscow tower a critical comment by an Orthodox priest.

The researcher came to conclusion, that the new blasphemy law and political, social and cultural conditions formed around it “have had a serious impact on media organisations, limiting freedom of speech and indirectly turning them into an instrument of a dominating religious organisation – Russian Orthodox church” and prevent audience of Russian media from getting an objective picture of civil society.

However, pressure on the press in Russia comes from other religions too. In January 2015, tens of thousands people gathered at a rally against French magazine Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons of the Prophet Mohammad in Grozny, the capital of predominantly Muslim Chechnya region. Kremlin-backed Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov not only accused European journalists in “insulting feeling of believers”, but also threatened those in Russia who supported Charlie Hebdo, including editor-in-chief of Echo of Moscow radio station Alexey Venediktov and former oligarch and vocal Kremlin critic Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

Earlier, the Chechen prosecutor’s office opened one of the first cases under the article 148 of Criminal Code, the renewed blasphemy law. In April 2014, a user of Live Journal was accused of “negative comments, expressing clearly disrespect for society and containing insulting remarks against people practicing Islam”. It was one of a few blasphemy cases that were opened in 2013-2014. However, in 2015 the use of article 148 of Criminal Code has stopped being a rareness.

In February 2015, another citizen of Chechen Republic was accused of insulting feelings of believers by posting a video on social networks. Also in February, the Investigative Committee began an initial inquiry into Tangazer opera staged in Novosibirsk theatre. In March, the first blasphemy case was opened in Ural region. In April, a user of the largest European social network, the St Petersburg-based VKontakte, was accused of insulting feelings of believers in his comments. At the end of October, VKontakte MDK was blocked by a St Petersburg court decision because it contained content that “insult feelings of believers and other groups of citizens”.

The imprecise wordings of the law and a wide range of its possible interpretations has arisen concerns of human rights activists. The several online campaigns were started to collect signatures under a petition calling for a repeal of the blasphemy law, but all of them failed to gain more than two thousand signatures.

This is one of a series articles on Russia published today by Index on Censorship. To read about the difficulties faced by Russia’s regional media in the face of growing political power, click here.