13 Nov 2015 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia

When the Tomsk-based station TV-2 ceased broadcasting earlier this year, Siberia lost one of its few independent stations. The channel was about as free as media can be in Russia: it wasn’t funded by a state or municipal budget.

The road to its closure began in April 2014 when an antenna malfunctioned. It took 45 days to get back on the air. When it resumed transmission in June 2014, Roskomnadzor – the Russian authority that oversees media and communications – revoked the station’s right to broadcast. A previous licence extension though 2025 had been issued as a result of a “computer error”, the agency explained.

On 1 January 2015, the station stopped broadcasting over the airwaves. In February 2015, it ceased to be an internet and cable station as well.

In Russia, independent media will not likely be shuttered because of critical coverage of the state. It will have its licence revoked because glitch or be silenced through a broken feeder or some other mundane technicality.

Early in the Putin era, Moscow-based national networks could be caught in a “dispute of economic entities” to silence narratives that were contrary to the government’s line. Media takeovers by businesses aligned with the government of President Vladimir Putin drew the world’s attention and criticism. But in Russia’s hinterland, the decline of media freedom was more precipitous.

Despite a professed respect for the rule of law in Russia, regional media outlets are caught between harsh oversight by local authorities and a lack of independent sources of funding. At the same time, business interests and regional governments are often more closely affiliated than in larger cities. Nepotism and conflicts of interest are rife while courts are hamstrung by corruption.

Journalists are often victims. According to Glasnost Defense Foundation, 150 journalists were killed in Russia during last 15 years. Authorities ignored crimes against journalists and tightened the screws by criminalising slander, which spurred lawsuits that helped destroy independent-minded free media.

When journalists do uncover corruption, regional authorities act to silence them by meting out punishment for “crimes” that the individual has committed. This is highlighted by the recent case of Natalya Balyakina, editor-in-chief of the newspaper Chaikovskie Vedomosti. A well-known journalist who investigated allegations of misconduct by local officials involving the area’s municipal housing and human rights violations, Balyakina was awarded the 2007 Andrey Sakharov prize for journalism.

On 22 October 2015, the Chaikovski city court sentenced her to three years of incarceration and 761,000 rubles ($11,818) in fines and damages. Balyakina was convicted of a crime that she allegedly committed five years ago, when she was director of the regional City Managing Company. Her former company has accused her of misappropriation and embezzlement.

Whether or not the allegations against Balyakina are true, Chaikovski regional authorities benefit by having yet another investigative journalist silenced.

Regional media must also contend with a dearth of independent funding. As a result, these outlets are often forced to sign affiliation agreements with local administrators. These deals come with restrictions on how the organisations can cover regional government activities.

Journalists reporting for these affiliated outlets say they receive direct instructions on what they can write about. The editor-in-chief of one newspaper was prohibited from publishing any issues regarding healthcare because there was nothing positive to cover. Regional events that are reported by national media — disasters or human rights violations — are not covered by local outlets due to positive news restrictions.

But even the cowed national media is under continued assault. The Russian Duma is considering a bill that will allow Roskomnadzor to compel media organisations to disclose foreign funding or material support. So software provided by Microsoft could cause a regional outlet to be labelled as a “foreign agent” on the same model of the NGO law that was passed in 2012.

Long under pressure from official censorship and self-censorship, journalists’ sources are now being constrained by punitive laws that have enlarged state secrets and toughened punishments. In June 2015, Putin signed a law that classified Ministry of Defence casualties during peacetime. The result is that journalists are now forbidden from reporting on the number of Russian soldiers killed in action in Ukraine or Syria.

The Federal Security Service (FSB) is also lobbying members of the Duma to pass a draft law that restricts freedom of information around real estate transactions. Some observers say that this will hinder work to uncover corruption committed by Russian officials carried out by bloggers and journalists.

The media in Russia became one of the core targets during the strengthening political powers in last decades, but the regional journalists are put in an especially weak position.

This is one of a series articles on Russia published today by Index on Censorship. To read about the chilling effect blasphemy laws have had on free speech in Russia, click here.

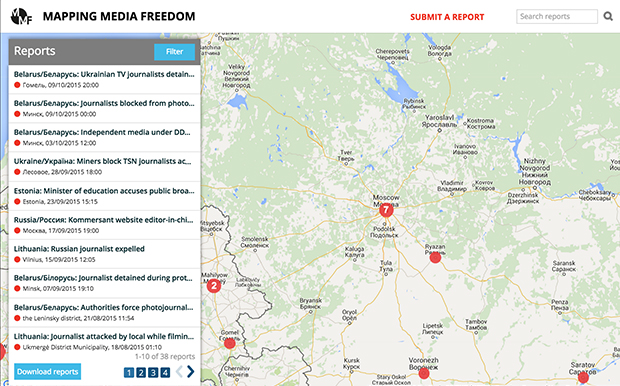

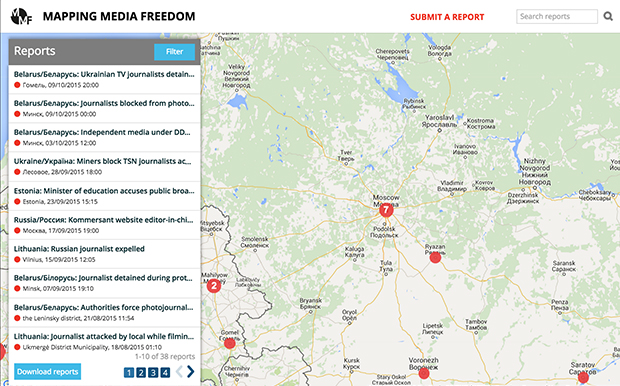

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

This article was posted at indexoncensorship.org on 13 November 2015

20 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia

On 6 November 2010, prominent Russian journalist Oleg Kashin was badly beaten with a steel pipe on his doorstep and nearly killed. He suffered a broken skull and injuries to his legs and hands — including broken fingers and one amputated digit. He was hospitalised in a coma and spent months recovering. Dmitry Medvedev, who was then President of Russia, visited him promising that the case would be solved and the attackers would be punished.

At the time, Kashin’s editor told the BBC that the attack was retribution for articles he had written and that he had recently reported on anti-Kremlin protests and extremist rallies.

Two months prior to the assault, Kashin had had an online quarrel with Andrey Turchak, the powerful governor of the Pskov region. According to the police investigation into the attack, the alleged organiser Alexander Gorbunov paid 3.3 million roubles ($53,000) to ex-employees of the security department of Zaslon, a company owned by Turchak’s family, to beat Kashin. Later the wife of Danila Veselov, one of the defendants, gave an interview to the Kommersant newspaper, claiming that her husband had met Turchak before the attack and had recorded the governor saying that Kashin had to be beaten so he “could not write anymore”.

After five years of investigation, in September 2015, Kashin publicly named the men who were officially accused of attempted murder. Despite evidence of the possible involvement of Turchak, who is a son of a friend of Putin, he has not been questioned about the attack.

On 3 October, Kashin posted A Letter to the Leaders of the Russian Federation on his blog. In it, Kashin wrote about his frustrations, saying: “Your will in Russia is stronger than any law, and simply obeying the law is an impossible fantasy.” The open letter accuses the government of hindering the investigation into his violent assault and ends as a strong indictment of the whole political system in Russia.

Moreover, the investigator who arrested the attackers was suspended from the case. His successor was quoted in Kashin’s letter saying: “There’s the law, but there’s also the man in charge, and the will of the boss is always stronger than any law.”

In his letter, Kashin directly accused the leaders of the country of protecting Turchak from any judicial responsibility.

“You’ve decided to side with your Governor Turchak; you’re protecting him and his gang of thugs and murderers. It would make sense for somebody like me — a victim of this gang — to be outraged about all this and tell you that it’s dishonest and unjust, but I understand that such words would only make you laugh. You have complete and absolute control over the adoption and implementation of laws in Russia, and yet you still live like criminals.”

Kashin admitted that he does not expect a fair punishment for the alleged mastermind of his beating: “I can see perfectly well that the worst thing Turchak faces now is a quiet resignation, timed long after any developments in my case. This is the only justice citizens can expect, and it means that your system isn’t capable of any kind of justice at all.”

Kashin’s case has become the symbol of impunity for attacks and murders of journalists. Hundreds of leading Russian journalists signed a petition that demands the police question Turchak. Some of them publicly boycotted a literature festival in the Pskov region, while the Kremlin and the Gorbunov’s press office remained silent.

Kashin said he wishes all journalists would boycott Turchak and continue to send requests about his role in Kashin’s case to government officials. However, that level of solidarity seems to be impossible when so much of the media is directly run by the Kremlin and do not dare to do anything without its approval, said Kashin. He also holds out no hope for support from the Russian Union of Journalists, which he describes as “a weird organization” that doesn’t function properly.

According to Glasnost Defence Foundation, over 150 journalists were killed in Russia in last 15 years. The majority of these cases remain unsolved. Those who are accused of obstruction of professional activities of journalists, rarely face a fair punishment. Between 2006-2014, only one such defendant was sentenced to jail.

The murder of Igor Domnikov, a journalist with Novaya Gazeta, in 2000 has become the first case in the history of modern Russia where the mastermind behind the killing of a journalist was officially accused. In this case, it was a former Vice-Governor of Lipetsk region Sergey Dobrovskiy. After 15 years of investigations, he was summoned to a court in April 2015, but a month later the case against him was dropped due to the statute of limitations.

Kashin said he will not be surprised if his case goes the same way. However, he stressed that the difference is that the investigators don’t need 10 years more as there is already evidence.

“We can see that the government is just not interested in punishing criminals,” Kashin said.

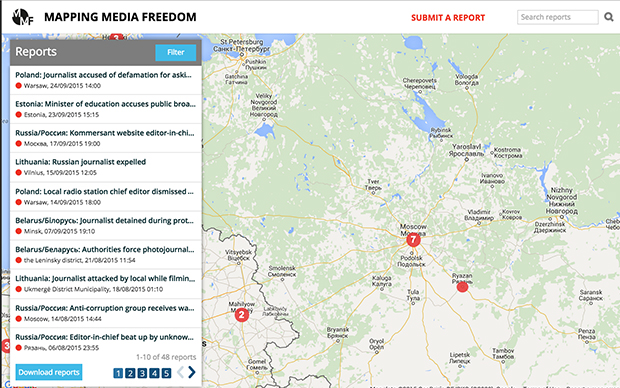

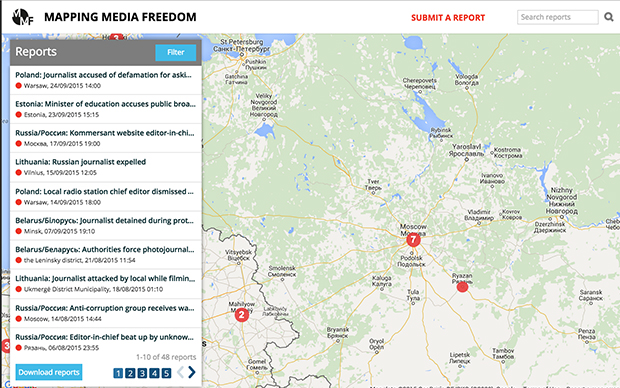

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

9 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Russia

The return of Vladimir Putin as president of the Russian Federation in 2012, after a wave of protests, was followed by the implementation of a new law that required non-governmental organisations receiving foreign support — in the form of funding or material aid — and engaged in “political activity” to register as “foreign agents” with the Ministry of Justice.

There are currently eight organisations advocating for media freedom and journalists’ rights included on a black list of 86 NGOs. Among them are organisations fighting for access to information (Freedom of Information Foundation), providing legal support to journalists (Rights of the Media Defence Centre and Media Support Foundation (Sreda)), organising education for regional reporters (Press Development Institute – Sibir in Novosibirsk and Regional Press Institute), an information agency (Memo.ru) and others.

Foreign agents have additional responsibilities and duties, including having to report twice as often and providing more information to the Ministry of Justice than other NGOs. A notice reading “Published by an NGO – foreign agent” must mark everything they publish, although some refuse to comply. In the Russian language, “foreign agent” has strong negative connotations associated with Joseph Stalin’s Soviet-era political repression. Some would say the term implies that NGOs are spies or traitors.

Only one organisation in Russia had voluntarily identified itself as a foreign agent before July 2014 when new rules allowed the Ministry of Justice to put NGOs on the list as it sees fit.

Some of the media freedom organisations are in the process of shutting down, including Sreda and Freedom of Information Foundation, while others, such as the Regional Press Institute (RPI) in St Petersburg, continue their activities but are forced to pay large fines.

Anna Sharogradskaya, the director of RPI, says she would never register the NGO voluntarily. “Article 51 of the Russian constitution says that nobody is obliged to give incriminating evidence against himself or herself and labeling the RPI would be not only incriminating evidence, it would be slander on our donors,” Sharogradskaya says. “So why should I break the law?”

Since 1993, RPI has provided seminars for journalists from Russia’s northwest region, offered its facilities as a venue for independent press conferences and meetings, and organised discussions on topical issues.

The organisation has come under increasing state pressure. In June 2014, customs officers at the Pulkovo International Airport in St Petersburg detained Sharogradskaya and searched her luggage. She missed her flight to the USA where she had been visiting scholar at Indiana University. Her notebook, memory stick and other gadgets were confiscated without explanation. For more than 10 months, Sharogradskaya was suspected of terrorism and extremism, after which she was cleared of all charges and her belongings were returned — although not in working order.

In November 2014, Putin promised that the St Petersburg regional Ombudsman Alexander Shishlov would look into the RPI case. “And he did: some days after this meeting, the Ministry of Justice put my organisation on the list of foreign agents,” says Sharogradskaya.

A court in St Petersburg fined RPI 400,000 rubles ($6,150) for refusing of add itself to the list voluntary. Half of the amount was paid by Russian and international journalists around the world, and the rest was added from Sharogradskaya’s personal savings.

Despite the pressure, RPI continues acting as an independent help desk for journalists, giving the region’s media, bloggers, initiative groups, democratic opposition leaders, and activists an opportunity to raise their voice at press conferences, and advocating for those who are in trouble with the authorities.

Many, including Sharogradskaya, believe that Russian civil society, including the media, faces increasing pressure. NGOs advocating for the freedom of the press must now spend more time and efforts protecting themselves instead of protecting journalists and other parts of the media.

Sharogradskaya says that above everything else, the lack of solidarity among journalists is a major concern. “Our work is to raise this solidarity. This is the only way to withstand the time of repressions.”

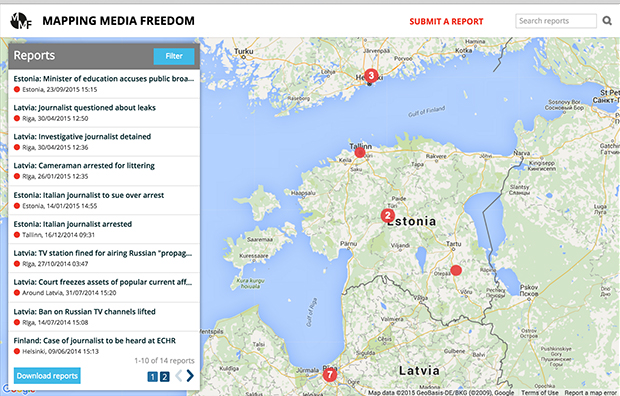

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|

2 Oct 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News

On 19 September, the Estonian Minister of Education, Jürgen Ligi, accused the Estonian Public Broadcaster’s new Russian-language TV channel of disclosing secret government data.

The news report that sparked Ligi’s accusation dealt with the government’s proposal to teach high school students in Estonian. This move has been seen as ignoring the rights of the Russian-speaking minorities in the country.

Ligi implied that the report caused difficulties for the government. He also announced that, as the information was most likely leaked, there would be an official investigation. The head of the news department at the public broadcaster ETV, Urmet Kook, has already explained that the information was not received through a leak but was discovered during a routine check of public documents on different ministries.

This is the latest in a series of actions by the government against the media for disclosing data. Politicians see themselves as having a monopoly on truth and consider the press as nothing more than troublesome meddlers.

There are no specific laws relating to the media in Estonia, so all commercial outlets — apart from broadcast channels — are governed like any other business. The diverse legal landscape is subject to many different interpretations and there are no defined meanings of terms like ‘public interest’ and ‘public figure’, which makes it difficult for journalists to operate.

A typical example of the excessive limitations on the media is the Act on Defence of Personal Data. On first glance, it appears to be a noble attempt to defend sensitive information about the private lives of individuals, such as political affiliations, race and heritage. However, a closer look shows that it effectively prevents many journalists from uncovering information in the public interest. For example, a hospital denied a journalist access to information relating to a lump sum payment made in compensation for malpractice. In another case, a press officer at the Office of Public Prosecutor refused to acknowledge a criminal investigation into a well-known businessman. On both occasions, the reason for refusing to disclose the data was its sensitive nature.

Some caution is understandable. Any ethical person understands the necessity of the right to privacy. But over zealous and arbitrary enforcement makes it very difficult for journalists to warn the public of corruption, crime and dangerous individuals. With the protection offered by the act, released convicts can demand media outlets remove a story relating to their crimes, trials and sentences. Offenders can effectively hide in plain sight.

While these legal hurdles are a fact of life for many journalists, freelancers face extra obstacles. Larger media companies are given preferential treatment by the government, as are journalists who present information in the desired way. Estonian media channels also tend not to work with freelancers on a one-time basis. Such practices hurt freelance journalists, especially younger writers who lack established sources and connections. Without proper access to information, they are deprived of a proper livelihood.

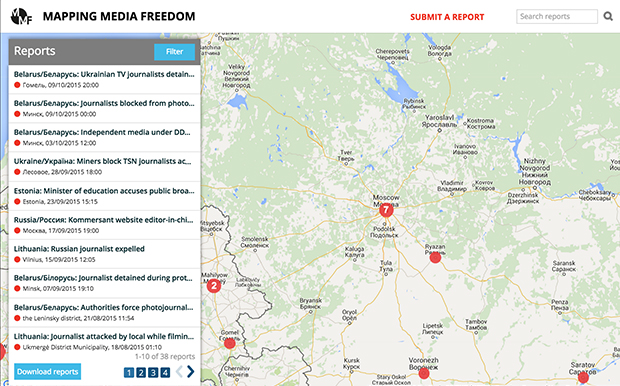

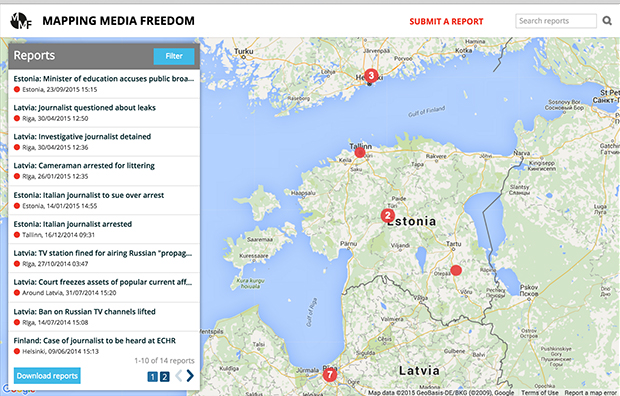

Mapping Media Freedom

Click on the bubbles to view reports or double-click to zoom in on specific regions. The full site can be accessed at https://mappingmediafreedom.org/

|