25 Jun 2014 | News, Russia, Ukraine

Wrestling for the rights to define the Ukrainian conflict, both Russia and Ukraine have utilised a range of tactics to control and limit media coverage in the region. This, alongside, the constant to and fro between media freedom and the skewed official lines has politicised the role of the media and manipulated perceptions of the conflict, further distancing coverage from reality.

Every fact is a battle to be fought and won. Who made up the Ukrainian protest movement? Activists and other members of civil society, or thugs, neo-Nazis or far-right extremists? What are Russia’s motivations? Geo-political revisionism, a nationalistic desire to rebuild empire or for the protection of a persecuted minority? There is not one answer to questions like these; indeed the answers appear to changes depending on where they come from.

A sure-fire tactic to control the number of answers on offer is to limit the number of journalists able to cover the story. There have been a number of cases across the region where journalists have either been detained or refused entry to key areas of the conflict. In May, it was reported that three journalists, including a writer for Russia Today, had been detained by Ukraine’s Security Services (SBU), with a further three refused entry at the border. With no clarification of the grounds for their detention, as well as refusing them access to legal representation, the legality of such acts is dubious at best; as Human Rights Watch (HRW) states: “Failure to provide information on the whereabouts and fate of anyone deprived of their liberty by agents of the state, or those acting with its acquiescence, may constitute an enforced disappearance.”

This however, is not a tactic employed exclusively by Ukraine. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), Russian authorities and pro-Russian separatists detained five journalists in Crimea and mainland Ukraine. On 2 June in Donetsk, unidentified armed men in camouflage raided the offices of regional newspapers Donbass and Vecherny Donetsk, detaining senior editorial staff, and accusing the publications of “incorrect reporting”. It is reported that the captor’s demands included the stipulations that the editors, “change the papers’ editorial policy”.

This proved to be effective. The deputy editor of Donbass stated that both his paper and Vecherny Donetsk were “discussing the separatists’ demands and were considering shutting down the outlets for fear of future retaliation”.

Beyond limiting the freedom of journalists covering the conflict, state-led censorship and propaganda is creating media vacuums in key areas, promoting narrow and strictly controlled interpretations of the conflict.

Attacks on the media in Russia have ramped up significantly following Putin’s return to the presidency and have taken on a distinct urgency with the continuation of the Ukraine conflict. One example is the legislation pushed through the Duma banning the publication of negative information about the Russian government and military. This positions Russian activities in Ukraine at the heart of controlling perceptions of Russia in the media. Quoting the official explanatory note to the legislation, HRW reports: “’The event in Ukraine in late 2013-early 2014 evidenced…an information war’, and demonstrated the necessity to protect the younger generation from ‘forming a negative opinion of [their] Fatherland.’”

Another key piece of legislation at play in this context is the “Lugovoi Law”, which allows Roskomnadzor, the Russia state body for media oversight, to block online sources without any court approval. One publication that was blocked was Grani.Ru due in part to its criticism of the state’s handling of the Bolotnaya Square protests. Grani.Ru have unsuccessfully appealed the ruling, but Yulia Berezovskaya, director-general of Grani-Ru is not surprised.

Roskomnadzor has not lost a single case against the media. The Office of the Prosecutor General and Roskomnadzor refused to indicate the “offensive” materials that should have been removed from the website so that access could be restored.

Berezovskaya continues to see this as part of a larger shift in the state’s relationship to the media in the light of the Ukrainian crisis: “The Ukrainian crisis is a major part of Russian TV news while domestic issues are not covered.”

Rolling out robust limitations against opposition or independent media outlets in Russia, at times irrespective of the events in Ukraine, guarantees in a large part the allegiances of media bodies covering the crisis. Indeed with many voices absent from the debate, the state can be confident the official line is being towed, at times, irrespective of fact.

The manipulation of fact has come to define a large part of pro-Russia content. Moscow Times reports “when Vesti.Ru described clashes between pro-Russian and pro-Kiev protesters in Simferopol…it showed footage of earlier protests in Kiev, which were more violent.” Channel One, when alleging that violence in Ukraine has sent a flood of refugees heading for Russia’s Belgorod region, used footage, not of the Ukrainian-Russian border, but of the Ukrainian-Polish border.

By restricting who can report on the Ukrainian crisis through access or censorship, the state can identify which untruths should be accepted as “truth” and which truths should not be seen. But as the conflict endures, the battle to shape perceptions, both home and abroad will continue. As it does, how can we identify the true actions, motivations and responsibilities, before untruths take hold and become something more, something resembling and assumed to be fact?

This article was published on 25 June 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Jun 2014 | Digital Freedom, News, Russia

@AndreiSoldatov and @cyberrights at the @IndexCensorship Brussels event on Press Freedom in Russia Turkey Azerbaijan. Photo: Ricardo Gutiérrez

On Thursday, Index hosted a discussion with five leading media experts from Turkey, Russia, and Azerbaijan. As journalists, bloggers, entrepreneurs and campaigners, they experience first-hand how censorship – online and off – is being ramped up in their countries, and they argue that their stories are still not being sufficiently heard.

Turkey’s Yaman Akdeniz and Amberin Zaman, Russia’s Andrei Soldatov and Anton Nossik, and Azeri blogger Arzu Geybulla shared shocking stories about journalists harassed in government-led smear campaigns, the arrests on spurious criminal charges of those who speak openly on social media, and the growing role of governments in blocking free expression online.

“The internet is becoming less and less independent of government interference,” Nossik told the Brussels audience.

Index works with writers – including authors, journalists and bloggers – and artists globally to help them tell a wider world about the threats they face. We are a platform that allows individuals to speak for themselves, and fights for those who cannot.

In the first article from one of our event speakers, Andrei Soldatov assesses the state of online freedom in Russia:

Since November 2012, we’ve been living in a country with the internet censored extensively by a nationwide system of filtering.

This system has been constantly updated ever since. Now we have four official blacklists of banned websites and pages: the first one is to deal with sites deemed extremist; the second is about sites blocked because of child pornography, suicide and drugs; the third consists of sites with copyright problems; the fourth, the most recent one, was created in February and lists the sites blocked without a court order because they call for non-sanctioned protests. There is also an unofficial fifth blacklist aimed not at sites but at hosting companies, based abroad, which have proven themselves not very cooperative with Russian authorities.

Technically, the internet filtering system in Russia is not very sophisticated. Thousands of sites were blocked by mistake, while if you want to access a blocked site you can do that using circumvention tools or even very basic things like Google translate.

At the same time very few people were sent to jail for posting critical things online, and relatively few new media were put under direct government pressure.

But surprisingly, freedom of expression on the internet in Russia has been hugely affected: users have become cautious in their comments, and internet companies, the largest in the country, even when invited to talk to Putin, are so frightened that they failed to raise the issue of regulation at the meeting.

The beauty of the Russian approach is that it doesn’t need to be technically sophisticated to be efficient. It also doesn’t need mass repression against journalists or activists.

So why is that?

Basically, the Russian approach is all about instigating self-censorship. To do this, you need to draft the legislation as broad as possible, to have the restrictions constantly expanded — like the recent law which requires bloggers with more than 3.000 followers to be registered — and companies, internet service providers, NGOs and media will rush to you to be consulted and told what’s allowed. You should also show that you don’t hesitate to block entire services like YouTube – and companies will come to you suggesting technical solutions, as happened with DPI (deep packet inspection). It helps the government to shift the task of developing a technical solution to business, as well as costs.

You also need to encourage pro-government activists to attack the most vocal critics, to launch websites with list of so-called national traitors, and then to have Vladimir Putin himself to use this very term in a speech.

All that sends a very strong message. And as a result, journalists will be fired for critical reporting from Ukraine by media owners, not by the government; the largest internet companies will seek private meetings with Putin, and users of social networks will become more cautious in their comments.

We have seen this before – the very same approach was used against traditional media in the 2000s. What made the situation on the internet special is that the government found a way to shift the task of providing a technical solution for censorship to companies, including the global ones, and make the companies pay for the system. The way global platforms seem to respond to that is not very impressive. Localisation cannot be a solution because it helps to localise the problems of censorship. Now the Russian search engine Yandex presents two different maps of Ukraine, with and without Crimea, for the Ukrainian and Russian audiences respectively.

The biggest problem with this approach is that it provokes governments to put more pressure on global platforms. One day Twitter was heavily criticised by a Russian official in a pro-Kremlin paper who threatened to block the platform completely. The next day Twitter rushed to block an account of Pravy Sector, one of the most-anti Russian political parties in Ukraine, and blocked it for Russian users.

This article was published on June 20, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Jun 2014 | Cameroon, Iran, News, Nigeria, Russia

The 2014 World Cup in Brazil starts today, 32 nations preparing to battle it out across eight groups in the first stage of the tournament.

This year’s competition, like so many before it, comes with its designated group of death. For those not familiar with the lingo, it means the group containing the highest amount of strong teams. Or even more simply put, the group most difficult to progress from. (You can’t accuse the beautiful game of holding back on the melodrama).

Index has looked at the countries taking part in arguably the biggest show on earth, and put together our own group of death — the freedom of expression edition.

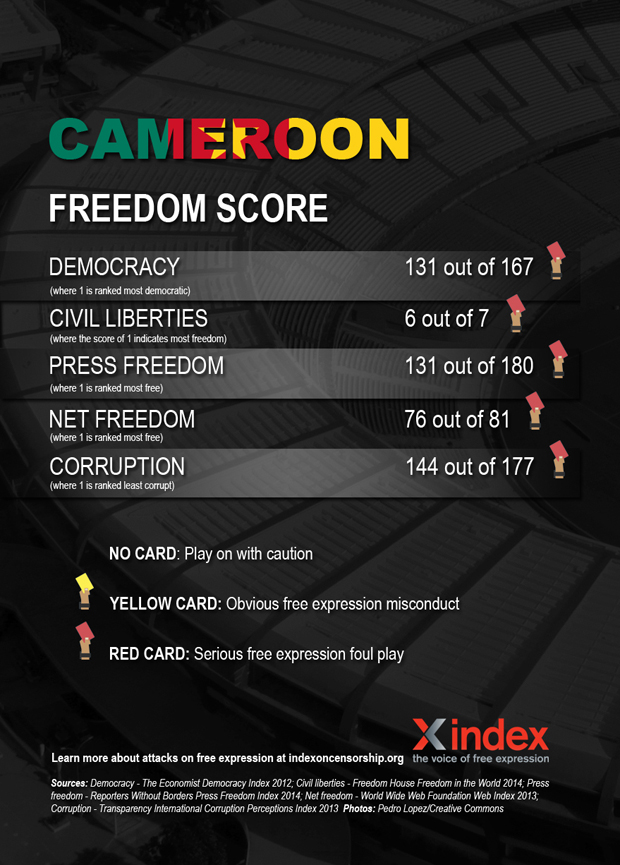

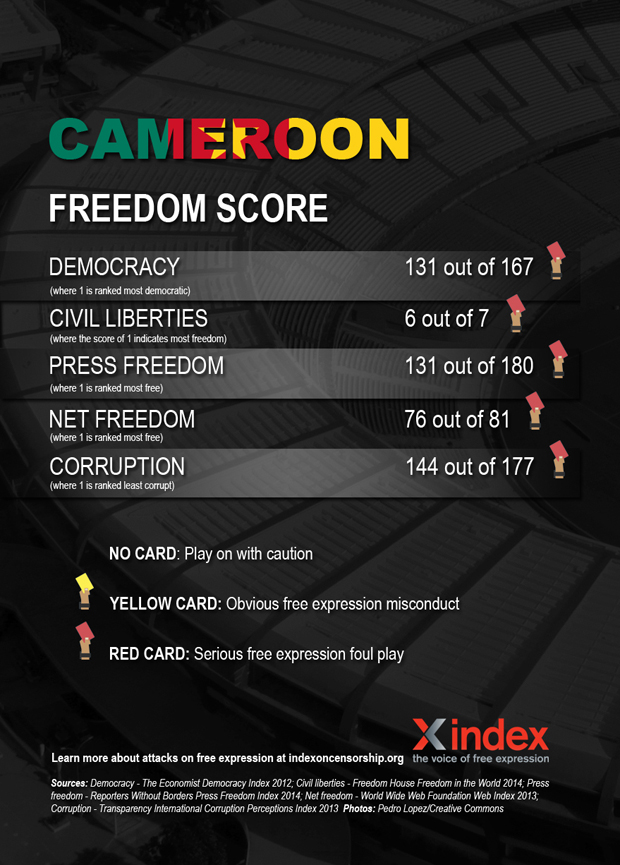

Cameroon

Cameroon — or the Indomitable Lions — have a solid track record in qualifying for the World Cup, having taken part seven time, more than any other African side. There were also the first African team to make it to the quarter final and are responsible for one of the most iconic moments in the tournament’s history. Their track record on free speech, however, is less impressive.

Freedom of expression is guaranteed in Cameroon’s constitution. Despite this, the government of Paul Biya — the country’s leader since 1982 — has been been accused numerous violations of free expression.

Large parts of the press are biased towards the ruling elite, while critical journalists face detainment, harassment and demands to reveal sources, among other things. Self censorship is widespread. In September 2013, 11 press outlets, including newspapers, radio stations and a TV station, were shut down for disrespecting “ethics and professional norms”. In 2010, former newspaper editor Germain Ngota, who had been investigating corruption allegations involving the state-run oil company, died in jail.

Freedom of assembly is often cracked down on. In 2012, former opposition presidential candidate Vincent-Sosthène Fouda and others were charged with “holding an unlawful demonstration”. The same year, security forces used tear against a crowd gathered to protest against Biya. In 2008, around 100 people were killed in clashes with police in anti-government riots.

Arts are not spared either. In 2013, Jean-Pierre Bekolo’s film Le President was banned in Cameroon because it discussed the end of Biya’s reign . In 2008, Lapiro de Mbanga, who criticised the constitutional change in term times that would allow Biya to stay in powers through song, was arrested.

Homosexuality is outlawed, and punishable by up to 14 years in prison. Human rights violations against LGBTI people, or those perceived to be, are “commonplace”. In July 2013, Eric Ohena Lembembe, director of the Cameroonian Foundation for AIDS (CAMFAIDS) was brutally murdered, in what friends suspect was an attack based on his pro-LGBTI advocacy.

Iran

Team Melli will hope that their fourth appearance at the World Cup will see them progress from the group stages for the first time. When he was elected almost a year ago, there was hope that President Hassan Rouhani would be a progressive force within Iran. The results so far have been mixed.

Since coming into power, Rouhani has taken some steps to improve press freedom, such as withdrawing 50 motions against journalists, and lifting some restrictions on previously banned topics. However, the government still controls all TV and radio, and censorship and self-censorship is widespread. The latest figures put the number of jailed journalists in Iran at 35. In January 2013, a group of journalists were arrested for allegedly cooperating with “anti revolutionary” news outlets abroad. Journalists’ associations and civil society organisations that support freedom of expression have also been targeted.

The internet and social media played a significant part in publicising and documenting the protests that followed the 2009 election, which many Iranians believed was fraudulent. The regime has banned Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and, recently, Instagram. The lead-up to the 2013 elections saw Iranian leaders tightening access to the web, and silencing “negative” news. While Rouhani — seemingly an avid Twitter user — has indicated plans to relax web censorship, the country’s plans to launch a “national internet” are said to be going ahead.

In May, eight people were jailed on charges including blasphemy, propaganda against the ruling system, spreading lies insulting the country’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on Facebook. Recently, a group of young people were arrested over a video posted of them singing and dancing along to the song “Happy”, which police called was a “vulgar clip” that had “hurt public chastity”. Some commentators believe the move was meant to intimidate Iranians and discourage online criticism.

Nigeria

Brazil 2014 marks 20 years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup, and the Super Eagles arrive at the tournament as reigning Africa Cup of Nations champions. The country’s leadership, however, is not a champion of free expression.

While parts of Nigerian media is controlled by people directly involved in politics, the country can also boast a lively independent media sector. However, journalists, especially those covering sensitive topics such as corruption or separatist and communal violence still face threats. Journalists have been arrested by security forces, and media outlets have been attacked by terrorists. Legal provisions such as sedition and criminal defamation also challenge press freedom. In 2011, a journalist was arrested over stories detailing alleged corruption in the Nigerian Football Federation.

The country’s freedom of information act was put in place in 2011. However, when human rights lawyer Rommy Mom tried to use the legislation to trace some 500 million of missing aid money allocated to his flood ravaged home state of Benue, he was met with threats from people connected to the state governor, and was forced to flee.

The Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act 2013 outlawing gay marriage and relationships, was signed into law by President Goodluck Jonathan in January. The unpublished law makes it illegal for gay people to hold meetings, and outlaws the registration of homosexual clubs, organisations and associations. Those found to be participating in such acts face up to 14 years in jail.

Nigeria has come under international attention in recent months for abduction of the Chibok school girls by terrorist group Boko Haram. Among other things, Nigerians responded with the powerful #BringBackOurGirls campaign. In June however, authorities seemed to ban an offline protest against the kidnappings, before quickly backtracking. It is also worth noting that the Nigerian government has targeted journalists in their “war on terror”.

Russia

Team Sbornaya travel to Brazil in the knowledge that next time in the World Cup rolls around, they will be playing on home soil. Russia of course, recently hosted another international sporting event — the 2014 Winter Olympics. However, global attention did not improve the country’s poor record on freedom of expression. In fact, experts predicted a rise in censorship ahead of the Olympics.

Press freedom has long been under attack by Russian authorities, with TV news currently providing little beyond the official government line. In the last few months, the relatively well-respected TV channel RIA Novosti was liquidated following a decree by President Vladimir Putin, and replaced by a new press agency headed by a Kremlin-loyalist. In January, Dozhd, a popular independent TV channel was dropped by satellite and cable operators over a controversial survey. For the remaining critical journalists, Russia — one of the countries with the highest number of unpunished journalist murders — is a dangerous place to work.

The crackdown on the internet is widely believed to have started with the protests surrounding the elections securing Putin’s third term in power, organised partly through social media, but it has recently intensified. The Duma has adopted controversial amendments to an information law, targeting bloggers with blocking and fines for anything from failing to verify information posted, to using curse words. Also recently, the founder of “Russian Facebook” VKontakte says he was forced out, with the son of the head of Russia’s largest state-run media corporation predicted to take over as CEO. In 2013, the Duma approved legislation allowing immediate blocking of websites featuring content deemed “extremist”.

Public protests are discouraged through forceful responses by police, arrests, harsh fines and prison sentences. The country’s recent anti-gay legislation also pose a big threat to free expression and assembly. The ban on “promotion” of gay relationships, means that any form of expression deemed to be “gay propaganda” can be shut down. The law has also lead to physical attacks on Russia’s LGBT population.

An earlier version of this article stated that Brazil 2014 marks ten years since Nigeria’s first outing at the World Cup. This has been corrected.

This article was published on June 12, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org