Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Rashid Razaq is a reporter for London Evening Standard and a playwright.

What is the solution to the Muslim Problem? Britain has tried multiculturalism; the French, a stricter enforcement of secularism. Neither has been an unequivocal success.

I’m afraid I don’t have the answer. I have only doubts and questions, whereas the terrorists have certainties and guns.

The only thing I can say with a fair amount of confidence is that the right not to be offended is a ridiculous thing. For there is no way to measure a subjective, emotional state other than to ask “Does this offend you?” in the same way you would ask “Are you tired?”, “Are you hungry?”, “Do you love me?”

One person’s silly cartoon is another person’s existential threat. Try as I might, I cannot get offended by a drawing. Maybe I’m a bad Muslim, maybe a true believer would be so mortally wounded by an image, any image, of the Prophet Mohammed that the only remedy is bloodshed. But I don’t think that’s the case. Much of the outrage is manufactured, stoked up by rabble-rousers for political purposes. Because that’s the brilliance of the right not to be offended (Irony — just to be crystal- clear): you can get offended on other people’s behalf, you can get offended about books you haven’t read, about things that may or may not exist.

Loath as I am to bring up scripture in a discussion about religion, the Islamic prohibition against making graven images of the Prophet Mohammed only really applies to Muslims. It stems from the same commandment not to worship false idols, intended to protect against idolatry.

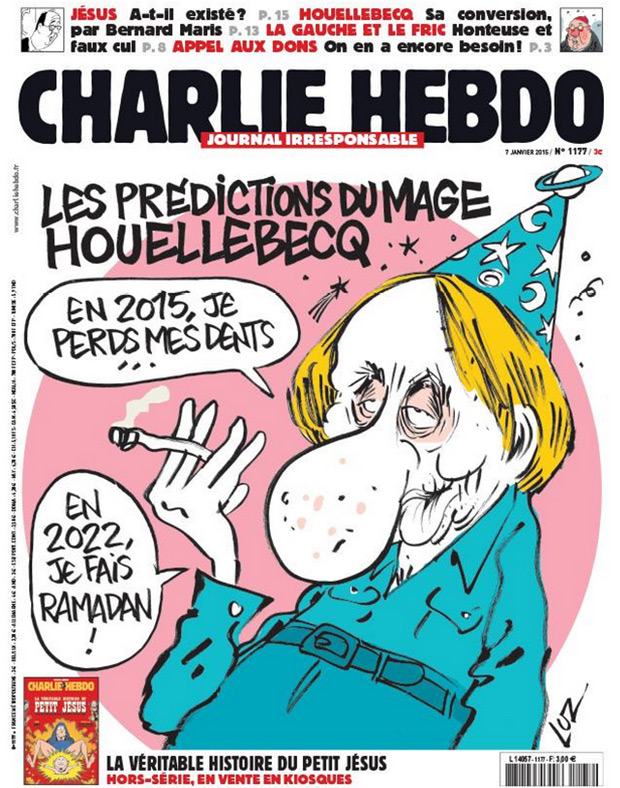

As far as I’m aware neither Stephane Charbonnier nor any of his leading cartoonists at Charlie Hebdo was a practising Muslim. The two victims believed to be Muslims, copy-editor Mustapha Ourad and policeman Ahmed Merabet, appear to have been collateral damage rather than targets.

So, just to make the murders even more pointless, you have Muslims killing non-Muslims for not sufficiently respecting something which they don’t believe in. Irony? I’m not sure.

Not that there is any justification. It is a shabby excuse for a heinous act, convenient religious cover for something that is probably nothing more than a twisted marketing stunt for al Qaeda in Yemen, if initial accounts prove to be true. The killings were not carried out to “avenge” the Prophet’s honour. Their real intent was to remind the West: “We’re still here”.

Many lofty and true words will be written about the need to protect the freedom of expression. But the attack on Charlie Hebdo wasn’t an attack on freedom of expression. It was an attack on an easy target. A group of middle-aged, unarmed cartoonists were never going to be much of a match for battle-hardened jihadists brandishing Kalashnikovs.

Satire is scary for people who can’t live with doubt. Because satire is all about creating doubt, questioning the way things are done, challenging those in power, pushing for change. I don’t know if the killings say more about the power of satire or the weakness of the gunmen’s supposed faith.

The jihadists want us to accept their narrative, that they are brave holy warriors and not just some over-sensitive, bloodthirsty bullies. But I have my doubts. I think the terrorists continue to provoke fear because they’re afraid. Afraid that we’ll realise their brand of religion is a joke.

The following letter was printed in The Telegraph:

SIR – The British sense of humour is famous around the world. Anyone who has watched Prime Minister’s Questions can see that even our MPs are funny – occasionally intentionally.

Satire is a vital tool for campaigning organisations to create debate, expose hypocrisy and change opinion. However, the importance of parody in public debate is not recognised in copyright law. This omission has led to the removal of material that is undoubtedly in the public interest – such as Greenpeace films taken down from YouTube.

Since 2005, two governments have run reviews on copyright, both of which said that there should be a copyright exception to allow parody.

We now have less than a week for the Government to commit to a vote. If it doesn’t, the opportunity to change the law may be postponed until after the next election. That isn’t funny. We call upon Vince Cable, the Business Secretary, and Lord Younger, the minister for intellectual property, to act now and ensure that an exception to copyright for parody is put into law.

Jenny Ricks

Director of Policy, ActionAid UK

Maureen Freely

President, English PEN

Kirsty Hughes

Chief Executive, Index on Censorship

John Sauven

Executive Director, Greenpeace UK

Thomas Hughes

Executive Director, ARTICLE 19

Ann Feltham

Parliamentary Co-ordinator, Campaign Against Arms Trade

Niall Cooper

Director, Church Action on Poverty

Simon Moss

Managing Director, Programs, Global Poverty Project

Phil Booth

Coordinator, medConfidential

Jim Killock

Executive Director, Open Rights Group

On 16 January, Greek blogger Filippos Loizos, responsible for the satirical Facebook page of Elder Pastitsios, was convicted for “malicious blasphemy and religious insult” and sentenced to 10 months in prison, suspended for three years.

Loizos has set up the page mocking a well-known deceased Greek Orthodox monk — Elder Paisios — by intentionally combining his name with a popular Greek food called “pastitsio”, a pasta based dish with béchamel sauce.

His arrest in late September 2012, came after Christos Pappas, an MP from the now-banned neo-fascist party Golden Dawn, posed a parliamentary question calling for the blogger’s arrest on the basis of the country’s anti-blasphemy laws.

Pappas is now facing charges of being involved in a criminal organization.

“My prosecution was somehow expected. At the time I drew a lot of attention on social media. The neonazi party saw ‘a chance’ in accusing me as a blasphemer, satisfying a very conservative society and inspiring strong national sentiments,” Loizos told Index on Censorship.

Loizos explained that the court did not understand his intentions — delivering a stinging rebuke for what he perceived as the monk’s dangerous nationalism and intolerance.

“The judges were very aggressive and did not want to understand my argument. They insisted on saying my intention was to insult because I hadn’t censored any posts of visitors which were considered blasphemous or vulgar. I would never do that. In a democracy we are all ‘condemned’ to disagree,” says Loizos.

Reactions in the press and on the internet after the blogger’s conviction were immediate and vociferous. Far-right publishing and Orthodox websites were gloating, while Loizos’ sympathisers and free speech advocates argued it was “a blow to freedom of expression”.

On 20 January 2014, Amnesty International expressed serious concerns over the case, while calling on Greek authorities to “repeal the anachronistic anti-blasphemy legislation”.

The Hellenic League for Human Rights (HLHR), the oldest human rights organisation in Greece, had earlier issued a press release, stating its “unfortunate certainty of an institutional and ideological setback that does not seem to end”.

“Today’s decision shows that freedom of speech, a fundamental pillar of social consistency in a state with ‘rule of law’, is being challenged not only by the enemies of democracy but by the judicial institutions,” according to the release.

Dimitris Christopoulos, an assistant professor of state and legal theory at the Department of Political Science and History at Panteion University in Athens, and vice president of the International Federation for Human Rights, told Index that “this decision is a message on how justice perceives political coexistence in society. It’s like saying ‘when you talk about God in a way we do not like, you will be punished’. In other words, people can joke about everything they want, except religion”.

Contrary to some allegations that the judges suffered social media illiteracy because of their age, Christopoulos told Index on Censorship that they were young and seemed to “fully understand the role of social media”.

In late September 2012, when Loizos was arrested, Vassilis Sotiropoulos, a lawyer and blogger specialising in internet legislation, told Index: “The legislature refuses to address the issue of internet censorship, thereby allowing law enforcers — prosecutors, police officers, judges and lawyers — to freely interpret and utilise the existing legal tools (…) the case of Elder Pastitsios provided perhaps the first example in Greece of an internet company disclosing information to the government in order to identify an individual accused of ‘alleged offences relating to religious satire’.”

However, it is not the first time cases regarding religious blasphemy have reached the courts. In 2012, controversial theatrical play “Corpus Christi” resulted in the legal prosecution and public harassment of the play’s director and actors by Golden Dawn members and Orthodox religious groups.

Legal experts told Index that there are several ongoing cases involving blasphemy in Greece and that the country should follow the Council of Europe’s recommendations and reports on abolishing “the offence of blasphemy”. According to these recommendations, freedom of thought and freedom of expression are being limited by blasphemy laws.

Loizos said he is going to appeal the verdict “for reasons of dignity”.

“We should abolish this blasphemy law in order to protect free expression,” he said.

This article was published on 23 January 2014 at indexoncensorship.org