17 Apr 2013 | Russia

Self-censorship has poisoned Russian media, art and other spheres.

In the past few years, criminal prosecution of artists and new laws have made it clear for those who criticise the Kremlin or Russian Orthodox Church in their creative work, will face consequences for portraying either of these institutions negatively.

A Russian artist came under fire for depicting members of Pussy Riot as religious icons

Just last week, the State Duma passed two controversial laws in the first hearing. One forbids obscene language in movies, books, TV, and radio during mass public events. The other stipulates criminal punishment — including five years in prison — for “insulting believers’ feelings”. Both laws, as far as human rights activists are concerned, limit artists’ freedom of expression, and encourage self-censorship.

Index spoke to three notable artists to find out how the art community deals with self-censorship, and the ever-increasing restrictions on freedom of expression in Russia.

Artyom Loskutov, an artist from Novosibirsk, is famous for holding “monstrations” — flash mobs with absurd slogans like “Tanya, don’t cry” and “Who’s there?”. In 2009, he was arrested on drug possession charges, but he claims that the marijuana was planted on him by police. A blood test proved that he had not taken any drugs, and his fingerprints were not found on the package. Three years on, he faced three administrative cases, and paid a 1000 rouble fine for creating icon-like images of Pussy Riot members Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alekhina and placing them on billboards. He was accused of insulting believers. He is currently appealing the court ruling in the European Court of Human Rights.

The artist told Index that the cases against him are acts of censorship, but vows to remain defiant and continue with his work:

The icons idea concerned two kinds of mothers: one mother is honoured as a saint, the two others — Tolokonnikova and Alekhina — were thrown in prison. The authorities, including the court, are becoming more insane, and one wouldn’t want to cause persecutions. But I can’t say that given that, I refuse to implement any of my plots. In the 90s my generation felt that we had nothing, except free speech, and all the 2000s attempts to take it away meet nothing but incomprehension

In 2010, The prosecutor’s office in Moscow’s Bassmany district examined the works of Moscow-based artist Lena Hades, “Chimera of Mysterious Russian Soul” and “Welcome to Russia”. Russian nationalists appealed to the authorities claiming these paintings insult Russians. The case did not go to court, but Hades told Index that Russian galleries feared exhibiting her paintings after the incident.

“Galleries are afraid of financial sanctions,” Hades says, “Although 95 per cent of my paintings are about philosophy rather than about social events, they are only exhibited in Tretyakov Gallery and Moscow Museum of Modern Art”.

Despite reduced chances of her work being exhibited, Hades still painted Pussy Riot’s members, and went on a 25-day hunger strike against their prosecution. The artist is no fan of self-censorship, even if it comes at a cost. According to her, no artist that responds to reality can accept self-censorship:

This is not courage, this is aristocratic luxury of doing what you want. Self-censorship is more harmful for a modern Russian artist than censorship. He is frightened of scaring away galleries and buyers and prefers to paint landscapes with cows — anything far enough from real social life

Artist Boris Zhutovsky has a long-standing relationship with censorship. In 1962, he was slammed by then Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who banned work by Zhutovsky and his colleagues. For several years following the incident, the artist faced difficulties in finding employment, and his work was not exhibited in the USSR.

Zhutovsky continues to court controversy today: in the past few years he has painted the trials of Russia’s most well-known political prisoners, businessmen Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Platon Lebedev, who were first convicted in 2005. He explained Russia’s culture of self-censorship to Index:

Self-censorship is based on fear, and the amplitude of this fear has changed throughout my life. In the times of Stalin, it was the fear of the Gulag and execution. In the times of Khruschev it was the fear of loosing a job or a country – a person could be forced to leave the Soviet Union. After Perestroika the fear shrank, and now the fear which nourishes self-censorship is the fear to anger your boss

He is optimistic that a younger generation of artists will not accept self-censorship as a standard, as the the era of Putin is far from that of Stalin, but only time will tell.

17 Apr 2013 | Newswire

Self-censorship has poisoned Russian media, art and other spheres.

In the past few years, criminal prosecution of artists and new laws have made it clear for those who criticise the Kremlin or Russian Orthodox Church in their creative work, will face consequences for portraying either of these institutions negatively.

A Russian artist came under fire for depicting members of Pussy Riot as religious icons

Just last week, the State Duma passed two controversial laws in the first hearing. One forbids obscene language in movies, books, TV, and radio during mass public events. The other stipulates criminal punishment — including five years in prison — for “insulting believers’ feelings”. Both laws, as far as human rights activists are concerned, limit artists’ freedom of expression, and encourage self-censorship.

Index spoke to three notable artists to find out how the art community deals with self-censorship, and the ever-increasing restrictions on freedom of expression in Russia.

Artyom Loskutov, an artist from Novosibirsk, is famous for holding “monstrations” — flash mobs with absurd slogans like “Tanya, don’t cry” and “Who’s there?”. In 2009, he was arrested on drug possession charges, but he claims that the marijuana was planted on him by police. A blood test proved that he had not taken any drugs, and his fingerprints were not found on the package. Three years on, he faced three administrative cases, and paid a 1000 rouble fine for creating icon-like images of Pussy Riot members Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alekhina and placing them on billboards. He was accused of insulting believers. He is currently appealing the court ruling in the European Court of Human Rights.

The artist told Index that the cases against him are acts of censorship, but vows to remain defiant and continue with his work:

The icons idea concerned two kinds of mothers: one mother is honoured as a saint, the two others — Tolokonnikova and Alekhina — were thrown in prison. The authorities, including the court, are becoming more insane, and one wouldn’t want to cause persecutions. But I can’t say that given that, I refuse to implement any of my plots. In the 90s my generation felt that we had nothing, except free speech, and all the 2000s attempts to take it away meet nothing but incomprehension

In 2010, The prosecutor’s office in Moscow’s Bassmany district examined the works of Moscow-based artist Lena Hades, “Chimera of Mysterious Russian Soul” and “Welcome to Russia”. Russian nationalists appealed to the authorities claiming these paintings insult Russians. The case did not go to court, but Hades told Index that Russian galleries feared exhibiting her paintings after the incident.

“Galleries are afraid of financial sanctions,” Hades says, “Although 95 per cent of my paintings are about philosophy rather than about social events, they are only exhibited in Tretyakov Gallery and Moscow Museum of Modern Art”.

Despite reduced chances of her work being exhibited, Hades still painted Pussy Riot’s members, and went on a 25-day hunger strike against their prosecution. The artist is no fan of self-censorship, even if it comes at a cost. According to her, no artist that responds to reality can accept self-censorship:

This is not courage, this is aristocratic luxury of doing what you want. Self-censorship is more harmful for a modern Russian artist than censorship. He is frightened of scaring away galleries and buyers and prefers to paint landscapes with cows — anything far enough from real social life

Artist Boris Zhutovsky has a long-standing relationship with censorship. In 1962, he was slammed by then Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who banned work by Zhutovsky and his colleagues. For several years following the incident, the artist faced difficulties in finding employment, and his work was not exhibited in the USSR.

Zhutovsky continues to court controversy today: in the past few years he has painted the trials of Russia’s most well-known political prisoners, businessmen Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Platon Lebedev, who were first convicted in 2005. He explained Russia’s culture of self-censorship to Index:

Self-censorship is based on fear, and the amplitude of this fear has changed throughout my life. In the times of Stalin, it was the fear of the Gulag and execution. In the times of Khruschev it was the fear of loosing a job or a country – a person could be forced to leave the Soviet Union. After Perestroika the fear shrank, and now the fear which nourishes self-censorship is the fear to anger your boss

He is optimistic that a younger generation of artists will not accept self-censorship as a standard, as the the era of Putin is far from that of Stalin, but only time will tell.

25 Mar 2013 | Volume 42.01 Spring 2013

Against a backdrop of heavy austerity measures in Greece, free speech and the right to protest are being both challenged and undermined. The policies are the result of agreements between the government and the so-called troika, made up of the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund and the European Central Bank. Since 2010, steps taken to restore fiscal balance have led to the impoverishment of large segments of society and unemployment has reached new highs: 26.8 per cent in October 2012. At the same time, the rise of the neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn, with an agenda of targeting immigrants, homosexuals and “dissidents” of all kinds, has created palpable social tensions. Police repress protests and political activity by a range of groups, including anarchists and leftists, a fact that has been widely documented. These tactics have been regarded by many as evidence that the government is adopting an authoritarian stance when it comes to criticism and dissent.

The current government, run by Prime Minister Antonis Samaras’s conservative New Democracy Party, took office in June 2012. In a report published in July 2012, Police Violence in Greece: Not just “Isolated Incidents”, Amnesty International stated:

The failure of the Greek authorities to effectively address violations of human rights by police has made victims of such violations reluctant to report them. … Between 2009 and the first months of 2012, numerous allegations have been received regarding excessive use of force, including the use of chemical irritants against peaceful or largely peaceful demonstrators, and the use of stun grenades in a manner that violates international standards.

In the report, Amnesty made “urgent recommendations to the Greek authorities”, urging them to ensure that police “exercise restraint and identify themselves clearly during demonstrations” and calling for them to improve “safeguards for those in custody and creating a truly independent and effective police complaints mechanism”. The mainstream media — owned mainly by business leaders seen as having a cosy relationship with politicians — have censored or fired journalists who have attempted to speak out about the costly bailout agreements with the troika.

Those who have reported on allegations of police brutality, such as Kostas Arvanitis and Marilena Katsimi of the Greek state-owned public radio and television broadcasting corporation ERT have also been targeted. On 9 October 2012, Thanos Dimadis, a correspondent for Greek TV and radio station SKAI, reported that bailout payments had been only “partial” and carried out “under a regime of strict economic surveillance”. Later that day, he received instructions from SKAI TV news director Christos Panagopoulos not to include that information in the afternoon and evening news reports. The text of his story was removed from SKAI TV’s website. Dimadis’s report was annoying for the government, which was keen to prevent details about the bailout from becoming public. Payments from the troika had been suspended since June, after a partial tranche was released. The authorities were worried that the public would believe that payments were conditional on even more stringent austerity measures. Dimadis complained to SKAI’s news directors, threatening to resign if they did not back up his report. He eventually quit.

Dimadis told me that senior management at SKAI argued that the reason they withdrew his report was that the prime minister’s office had dismissed it as false. Moreover, Dimadis’s reactionwas described by SKAI as “over the top”.

Censoring the news

The government’s modus operandi is best illustrated by the Kostas Vaxevanis case. Vaxevanis, an investigative journalist and publisher of Hot Doc magazine, was arrested on 28 October 2012 for publishing the names of over 2000 Greek citizens who held Swiss bank accounts, dubbed the “Lagarde list”. The story focused on alleged tax evasion by wealthy Greeks during a time of economic crisis.

“A few months ago, before the release of the ‘Lagarde list’ and my aggressive arrest, there was an organised attempt to destroy my professional reputation: a publication presenting a fake receipt attempted to incriminate me as being on the payroll of the National Intelligence Service (EYP). I realised I was under heavy surveillance and one night I was ambushed by strangers at my home,”Vaxevanis told me in an interview.

During our discussion, on 26 December 2012, Vaxevanis said free speech in Greece was coming under attack yet again: “It’s not something new. When you have ongoing dealings between politicians and businessmen who own media groups, then it comes as no surprise that journalists are driven to self-censorship. Take a look, for example, at the non-existent coverage of the Reuters story on the Piraeus Bank case. You have such a big story, but what you see in the newspapers instead is an advertisement by the bank.”

On 1 November, Vaxevanis was acquitted and cleared on changes of violating privacy laws. But two weeks later, the prosecutor’s office ordered a retrial, claiming the original verdict was “legally flawed”. He could face up to two years’ imprisonment if he is sentenced. In April 2012, Reuters reported on an investigation into documents, including financial statements and property records, relating to Michalis Sallas, executive chairman of Piraeus Bank, and his wife, Sophia Staikou. The press report said “the couple may also be emblematic of the lack of transparency and weak corporate governance that have fuelled Greece’s financial problems”.

But according to journalist Apostolis Fotiadis, no major national or international media outlet reported on the lawsuit filed by Piraeus Bank against Reuters, though the New York Times anda couple of independent journalists attended the trial, including Fotiadis. The ruling is still pending.

On 29 October 2012, a popular morning talk show on the Greek state broadcasting corporation, ERT, was suddenly suspended, following a decision by ERT’s general director of news, Aimilios Liatsos. Shortly before the show was dropped, Kostas Arvanitis, co-presenter of the programme, and his colleague Marilena Katsimi had made comments on air about the minister of public order’s response to an article published in the British newspaper the Guardian written by Helena Smith.

Arvanitis told me:

I’ve been working as a journalist for 25 years. I’ve never experienced anything like this — not to this extent and with such intensity, at least. I consider what happened as aggressive meddling by the political system. It’s becoming more and more clear: every question that is different, every perspective that is different is considered provocative. You can understand what’s happening if you take a careful look at the media coverage of strikes.

Influential columnists and unsigned editorials very often neglect the reasons lower and middle working classes decide to go on strike. Instead of shedding light on their requests, these outlets prefer to present the strikes as instances of “abusing the public space” or “disturbing public peace”. This is the typical official government response as well. In the broader context, of course, this approach fails to report on the growing pressure on workers — on those who still have a job but with reduced salaries, and on those without one.

A Guardian article written by Maria Margaronis was published on 9 October and mentioned allegations of police brutality against protesters. It also referred to and confirmed an earlier article,published on 28 September, written by Helena Smith, that quoted ‘analysts, activists and lawyers’ as saying that the “far-right Golden Dawn party is increasingly assuming the role of law enforcement officers on the streets of the bankrupt country, with mounting evidence that Athenians are being openly directed by police to seek help from the neo-Nazi group”.

Margaronis also wrote:

Fifteen anti-fascist protesters arrested in Athens during a clash with supporters of the neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn have said they were tortured in the Attica General Police Directorate (GADA) — the Athens equivalent of Scotland Yard — and subjected to what their lawyer describes as an Abu Ghraib-style humiliation. If it hadn’t been for the Guardian stories, it is highly unlikely that Golden Dawn’s purported connection with the police would have reached a foreign audience — or the Greek public. The fact that these claims never made the Greek press and that Arvanitis was censored for simply commenting on one of the articles shows just how prevalent censorship is in Greece today.

Dimitris Katsaris is a lawyer for four of the protesters who alleged that they were tortured in GADA after they were arrested during the 30 October protest. He says the way the situation has been handled is a clear “indication of censorship … interviews with the anti-fascists took place in a climate of terror; at the end, the policemen tried to grab me and push me away while I was complaining to them. All of this has been recorded.” However, the censorship didn’t stop there.

Ignoring the truth

Minister of Public Order Nikos Dendias claimed on SKAI TV talk show New Folders on 16 October that the Guardian report on police brutality was false, and threatened to sue the British paper if no proof of torture was found. He questioned the source of the photographs in Margaronis’s article — which showed an injured protester — and claimed that since the anti-fascists hadn’t gone on record with their names and reports, and hadn’t filed a lawsuit against the police, the Guardian was not justified in publishing the story.

Dendias also denied assertions that the arrested protesters were afraid to go on record because they had been threatened by police or extremist Golden Dawn supporters. According to Katsaris, although SKAI and the New Folders’ presenter Alexis Papahelas were already in possession of the photographs indicating police brutality at the time they interviewed Dendias, they did not report on the evidence or broadcast the photographs; had it not been for SYRIZA MP Dimitris Tsoukalis’s intervention on the show, the photos wouldn’t have been shown on air. “From the moment the Guardian’s report was published,” Katsaris says, “I was in contact with New Folders’ editor-in-chief. A week before the show I was providing him photos and evidence that proved torture by the police.” Katsaris says he called the editor-in-chief and asked him to intervene, but after many calls, he was told there was “‘no sufficient airtime” to provide the other side of the case. “So I could not contrast the ministers’ claims. I even asked them, given the material they had, to question the minister in a fair journalistic manner. They didn’t.”

It seems that every time a story about political actions by anti-fascist protesters unfolds, the censorship machinery of the government and Golden Dawn is set in motion. Niko Ago, an Albanian national who had been working as a journalist in Greece for 20 years, faced deportation after publishing a report about alleged criminal activity by Golden Dawn spokesman Ilias Kasidiaris, who is a member of parliament. Ago revealed that Kasidiaris was facing charges for allegedly participating in a 2007 attack on a postgraduate student and for illegal possession of a firearm .Since then, Ago has been receiving threatening emails containing defamatory and racist comments, some of which he published, including one that said “Fuck you, Albanian … all you fucking Albanians are going to get what you deserve.”

Muzzling grassroots dissent

A great deal of pressure has also been brought to bear on independent, non-corporate media collectives or individuals who offer grassroots coverage. On 20 December 2012 and on 9 January 2013, police operations were carried out at the Villa Amalias squat in Athens, which has been an important meeting place for alternative political movements for the last 23 years, and at the Radiozones of Subversive Expression, an Athens-based radio station at the University of Economics and Business (ASOEE). Anarchists, leftists and political dissidents used both sites to organise labour, anti-fascist and antiracist rallies. As part of the operations connected with the ASOEE raid, in late December, anti-riot squads and police targeted immigrant street vendors originally from Nigeria, Morocco and Bangladesh who were selling pirated CDs and wooden animal figurines, as well as those who were regarded as supposedly condemning Greece to an economic decline, as the Radiozones website put it. The government, as well as Golden Dawn, tends to regard the economic activities of immigrants as detrimental to the national economy and as a threat to local workers.

Last October, during German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s visit to Greece, nearly 100 arrests took place, as Avgi newspaper reported. During the 6-7 November general strike, a group of parliamentarians from SYRIZA denounced the massive presence of undercover police on the streets of Athens. According to the coalition, they were both acting as provocateurs among peaceful protesters and arresting people who simply looked “suspicious”. The policy of pre-emptive arrests has been repeatedly called unconstitutional by human rights organisations, including the Hellenic League for Human Rights.

Tomasz Grzyb/Demotix

During the annual Athens’ Polytechnic School rally on 17 November, dozens of pre-emptive arrests were reported on the website of the weekly political newspaper Kontra and activist websites documented many individual complaints. Indymedia Athens, the local collective of the international grassroots and activists network, published two complaints from citizens arrested on the day of the rally. In both cases, individuals were detained before the demonstration and were kept in custody for five hours without being allowed to contact a lawyer.

Mainstream media failed to report the events, while the government officially ignored complaints. Most news on the events came from blogs and free expression activists.

Online censorship

This systematic abuse is also taking place in the online environment. After posting a Facebook page that ridiculed a well-known Greek Orthodox monk, in late September 2012, a 27-year-old man was arrested on charges of‘”malicious blasphemy and religious insult”. Many online activists and commentators reflected that the page, called Elder Pastitsios the Pastafarian (which intentionally combines the name of the monk with a popular Greek food), angered members of Golden Dawn, who called for the man’s arrest under Greece’s anti-blasphemy laws. Free expression advocates responded, with the hashtag #FreeGeronPastitios trending on Twitter, and a petition addressed to parliament calling for the immediate release of the Facebook user was circulated online Vassilis Sotiropoulos, a lawyer and blogger specialising in internet legislation, writes:

“The legislature refuses to address the issue of internet censorship, thereby allowing law enforcers (prosecutors, police officers, judges and lawyers) to freely interpret and utilise the existing legal tools. This phenomenon has sometimes led to misunderstandings, which restrict individual rights of freedom of expression and privacy. Sotiropoulos added that the case of Elder Pastitsios provided perhaps the first example in Greece of an internet company disclosing information to the government in order to identify an individual accused of ‘alleged offences relating to religious satire’.

When considering freedom of speech as a universal human right, it is important to comprehend the social and economic context of our times. Currently, the political and economic elites, in Greece but elsewhere in Europe as well, are repositioning themselves within a capitalist system that is undergoing a continuous transformation.

Speaking to Al Jazeera, William I Robinson, Professor of Sociology and Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, argued that we are currently living through a phase of capitalism where “nation-state constraints” no longer apply. He stated that the “the strength of popular and working class movements around the world, in the wake of the global rebellions of the 1960s and the 1970s”, are now being effectively and successfully undermined.

Historically, during periods when there have been attempts to devalue the working class, there have also been challenges to the fundamental right to voice dissent, which has had a direct impact on efforts to improve living conditions. The current economic crisis, then, fits this model; it can also be used as an effective tool for the far right and those using fascist rhetoric to attack immigrants and workers.

Freedom of speech and protest in Greece must, then, be seen in very specific terms. The right to free expression is being systematically and effectively challenged by formidable political and economic agendas. It is crucial that activists, journalists and those being censored and abused continue to make their voices heard.

Christos Syllas is a freelance journalist in Athens. He tweets from @csyllas

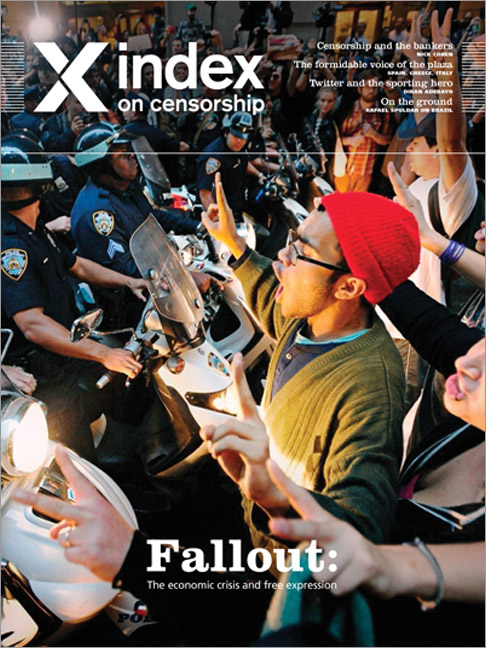

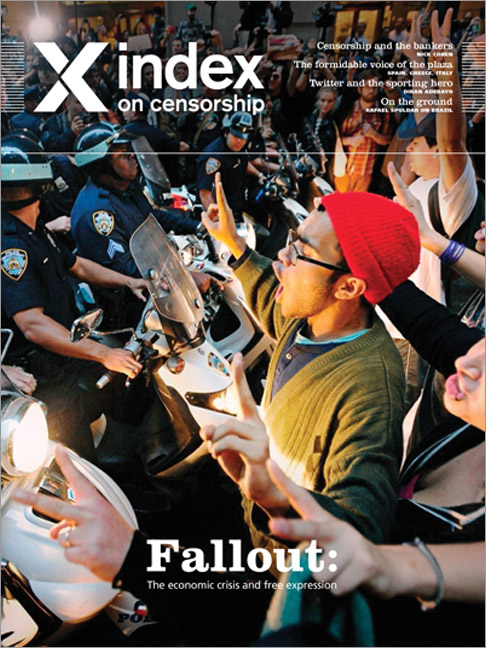

20 Mar 2013 | Press Releases, Volume 42.01 Spring 2013

As we prepare for Index’s annual freedom of expression awards, where we celebrate some of the world’s most courageous free speech heroes, we are delighted to announce the redesign of Index on Censorship magazine, published by SAGE. In addition to the in-depth journalism we’ve always placed at the heart of Index on Censorship, the magazine will feature a wider range of lively opinion snapshots, debates, views from the ground and interviews. A

“The magazine’s fresh new look reflects Index’s increasingly international outlook and role in setting the agenda for freedom of expression,” said Index Chief Executive Kirsty Hughes.

The new design was created by Matthew Hasteley, who said:

“Tackling a brief to modernise a magazine of Index’s heritage is a task you approach with a great degree of care and respect. The magazine balances the weight of its past accomplishments with its current, ongoing struggle against censorship around the globe, and the design need to reflect that tension — honouring the gravity of its editorial content.”

The latest issue, launched today, looks at new threats to free expression posed by the economic crisis, from restrictions on reporting and demonstrations to the rise of extremism. Is a decline in trust and a climate of self-censorship dominating the political, cultural and media landscape?

Christos Syllas looks at the threats to journalists and activists in crisis-stricken Greece and Spanish journalist Juan Luis Sánchez reports on the Spainish government’s moves towards criminalising one of the most powerful movements in recent years. The issue also features Natalie Haynes on political comedy and Nick Cohen on the secretive habits of big business and banking.

Our “In Focus” section will explore Index’s global themes, from digital censorship, government censorship and surveillance to religious and cultural pressures, restrictive laws and access to information. This issue also features Diran Adebayo on Twitter and the sporting hero and Dominique Lazanski on the future for online freedom.

If you would like an copy for review, please contact Pam Cowburn: [email protected]

Click here to subscribe.