12 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Serbia

Around 1 am on Thursday 3 July 2014, Davor Pasalic, editor of Serbian news agency FoNet, was brutally assaulted as he made his way home from the office. Pasalic, who had stopped for pizza, was accosted by three young men who demanded money and told him they had a gun. Pasalic refused and the men began beating him while shouting nationality-based slurs. Pasalic estimates that they struck him about 30 times before leaving him alone. The injured man then crossed a bridge leading to his apartment and was again attacked by the three men. The two attacks left him with cuts and bruises to his head and body. Four of his teeth were broken or knocked out.

“I have no clue why those three guys attacked me,” Pasalic told Index on Censorship. “One of the guys asked me: Are you a Croat? I was born in Belgrade. I have no accent. I look like every other citizen of Belgrade. Nobody has ever asked me that question before. How did he figure out that I am ethnic Croat?”

Six months have elapsed since the brutal assault, but police have made no progress in unmasking the culprits or discovering their motives. Nebojsa Stefanovic, Serbian minister of internal affairs, insists authorities are handling the incident as a priority, while Pasalic has said he is not certain whether police are unwilling or unable to resolve the assault. Journalists’ associations in Serbia are worried, vowing they “won’t allow” the beating to become just another case in the long line of unresolved attacks on media workers in Serbia.

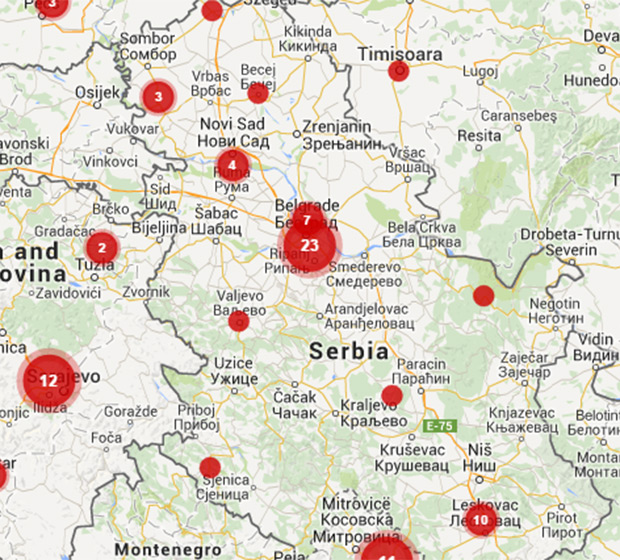

From 2008 to 2014, Serbian has seen a total of 365 physical and verbal assaults, intimidations and attacks on property of media professionals, according to a report by the Independent Journalists’ Association of Serbia (NUNS). The numbers should be taken as provisional, it added, since many media workers do not report attacks. The real figure is likely higher than the official one. Since May 2014 alone, Index’s European Union-funded Mapping Media Freedom has received 48 reports of violations against Serbian media including attacks to property and intimidation and physical violence, one of which was the attack on Pasalic.

“In the period between 2008 and 2011 less than 10 per cent of all attacks were processed,” NUNS said. “We also have problems with the judicial process, even in cases where the identity of the aggressor is very obvious. In Serbian courts it is common for attackers to receive minimum sentences, which obviously encourages attacks,” said NUNS’ President Vukasin Obradovic in a statement. He believes this situation leads to self-censorship within the country’s press.

Media freedom violations are also covered in the annual reports on human rights in Serbia by the Belgrade Center for Human Rights (BCHR). In 2013 they reported, among other things, that hand grenades had been thrown at the home of the owner of the website Telegraf and that four journalists were under 24 hour police protection. In 2012 they pointed out, pointed out that despite a high number of attacks on the media, trials of press workers progressed faster than trials of perpetrators of attacks on journalists: “Minister Velimir Ilic was at long last found guilty and fined almost 1.4 million RSD for physically assaulting a journalist of the Novi Sad TV Apolo back in 2003. The assailant on TV B92 cameraman in 2008 was sentenced to one year in jail in 2012. The men who threatened to kill the author of the B92 show Insider Brankica Stankovic in 2009 were sentenced to 16 months’ imprisonment and six-month and one-year conditional sentences respectively.”

BCHR noted in its 2011 report that some court judgments confirmed the suspicion that perpetrators who attack journalists can count on lenient sentences. In 2010, they found that journalists were mostly being attacked by politicians, policemen and local businessmen dissatisfied with their reporting, and that — like in the previous years — most of the perpetrators went unpunished.

There are also cases where law enforcement authorities appear to simply not be doing their jobs, according to lawyer Kruna Savovic, who is part of the NUNS legal team. Speaking to Radio Free Europe, she shared the story of a journalist who reported death threats against him and his mother to the police. He stated the identity of the suspect, named witnesses and filed a report, but instead of processing the case, officers told him he would be charged if he continued to bother them.

The attacks on Pasalic were not captured by surveillance cameras in the area, and according to Stefanovic’s statement, the lack of video is complicating the investigation. The minister also asserted that a report was not filed on the night of the incident. Pasalic refutes that, saying he had sought medical treatment at the military medical academy after the assaults and told the on-duty officers what had occurred.

Serbian journalists’ associations have been unified in condemning the incident. “Serbian society is burdened with numerous attacks on journalists which remain unsolved and their perpetrators unpunished, sometimes for decades. This encourages the attackers and contributes to spreading fear and insecurity both among journalists and the society as a whole,” the Association of Independent Electronic Media (ANEM) pointed out.

The international community has also taken note. “Journalists’ safety is a key issue in the OSCE region. There must be no impunity for crimes committed against media workers”, said OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatovic, and in its 2014 progress report on Serbia, the European Commission stressed that threats and violence against journalists “still remain a concern”. The Commission and other international non-governmental organisations urged Serbian authorities to keep their promised to investigate the killings of journalists Radislava Dada Vulasinovic in 1994, Slavko Curuvija in 1999 and Milan Pantic in 2001, as well as other attacks.

So far a Serbian special commission, which was created in 2013 and tasked with reopening the unresolved murders of journalists has achieved progress in the case of Curuvija. The commission found information that connects four former state security officials with the killing. They were all charged. Three of them were imprisoned while “one of the indicted men is believed to be on the run and living in an African country”. In 2014, NUNS reported, there was only one journalist under 24 hour police protection.

After six months of investigation and zero progress Pasalic ironically says that his case is “no big deal.” But, he said that the assault has had no impact on his work.

Veteran B92 journalist Veran Matic has worked against impunity and to bring murders of Vulasinovic, Curuvija and Pantic to justice. “The culture of producing fear is the most efficient form of censorship,” he told Index last November. But he added: “In the same way as impunity restricts freedom of speech, solving of these cases, at least 20 years later, will surely contribute to journalists being encouraged to do their job in the best possible way.”

Recent reports from mediafreedom.ushahidi.com

Serbia: Prime minister calls BIRN’s journalists “liars”

Serbia: Journalist fired after demotion

Serbia: “Doctors” send death threats after report

Serbia: Mayor criticised for implying journalists not welcome

Serbia: Journalist demoted after publishing report

This article was posted on 12 January 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

29 Oct 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Serbia

Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic speaking at LSE (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

It wasn’t quite a remote controlled drone carrying a provocative political message, but Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic’s Monday night lecture at the London School of Economics (LSE) came with its own controversial incident.

“What can you say about the total censorship of all opposition media”, Vucic was asked by a young woman in the audience just as the premier sat down for the question and answer portion of the event. She explained that she was representing Nikola Sandulovic, an opposition politician from the Serbian Republican Party, who was sitting beside her. Sandulovic said later he had travelled to London to confront Vucic.

Chaos ensued. Sandulovic claimed, among other things, that a police officer connected to Vucic had threatened to kill him and that he had evidence contained on a CD he held aloft. Vucic hit back that the Republican Party had only 0.01% of public support, and disputed Sandulovic’s assertion that he had been an adviser to former Serbian Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic, who was assassinated in 2003. Accusations flew across the room until LSE’s moderator James Ker-Lindsay finally managed regain control of the situation.

After the event, Sandulovic told Index he came to London because the media in Serbia ignore him and his party, apart from when government-friendly outlets attack him.

That press freedom was a popular topic on the night did not comes as a surprise. Serbia has seen a string of censorship incidents during Vucic’s time in power, as Index and many others have reported.

The prime minister himself brought up the press in his introductory lecture. He explained how his government has passed several new laws aimed at improving the media landscape, and complained that despite this, they are “scapegoated”. He directly addressed the recent controversial cancellation of a political talk show, Utisak Nedelje (Impressions of the Week), saying authorities have been subjected to a blame campaign for what was a commercial decision. Supporters of the show, including host Olja Beckovic, say it was down to political pressure.

In a joking reference to his infamous role under Slobodan Milosevic, he said he had been the “worst minister of information”. Curiously, he also used this former job as a counterargument to critics, arguing that his past had made it easy to blame him for any instance of censorship.

But this didn’t seem to stop the press-related questions, though none of the journalists present were chosen to ask one. Apart from the memorable Sandulovic intervention, an audience-member pointed out that Utisak Nedelje wasn’t the only show to have been taken off air in recent times.

If there was an overarching theme to the night, it was that it seemed to showcase different — some would say conflicting — sides of Vucic and his administration. He reminded the audience that Belgrade had recently organised a successful Pride parade, before adding that he didn’t want to attend. To have that choice, he argued, was a real mark of freedom.

There were, of course, questions about the football drone. While Vucic said he didn’t want to share his own views, he said UEFA (European football’s governing body) saw Serbia’s side of the story by awarding them the win, before pointing out that Serbia carries its share of the responsibility. The planned state visit from Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama — the first in 68 years — will go ahead, he also confirmed, despite the post-drone postponement.

In response to questions about relations with Russia — just weeks after the Belgrade military parade where Vladimir Putin was the guest of honour — he said the two countries would continue to build their relationship, but that this would have no impact on Serbia’s ultimate goal of European Union accession.

Much has been made of Vucic’s apparent journey from Milosevic man to EU enthusiast. He seemed to reference this as he said he is “not perfect” and that he works “every single day” to change and better himself. But on Monday, he left more questions than answers about the direction he is taking Serbia in.

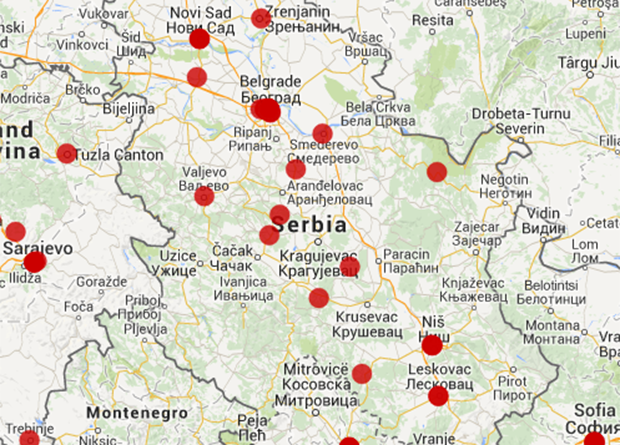

Mapping Media Violations in Europe: Serbia

Five media outlets targeted with DDoS attacks

Protesters criticise cancellation of political talk shows

Deputy mayor fined for insulting journalist

Macedonian journalist released from extradition detention

Photographer injured by anti-pride parade protesters

This article was originally posted on 29 October at indexoncensorship.org

29 Sep 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features, Serbia

Serbian journalists last night gathered outside the studios of national broadcaster B92, in protest at the decision to cancel politics talk show Utisak Nedelje (Impressions of the Week).

B92 claims the popular show — on air since 1991 — has not been cancelled but postponed due to a breakdown in negotiations with its author and presenter Olja Beckovic, according to news site Balkan Insight. The channel says they had offered to continue broadcasting the show on its national frequency channel — its home since 2002 — until November, when it would be bumped to the cable channel B92 Info. But Beckovic says the show has been banned following political pressure.

“I absolutely never experienced such blackmail and pressure before,” she told website Vesti in an interview published on Friday. “And there’s something very interesting about that. People say this is a return to the 1990s. No it’s not, it’s worse than the 1990s.”

In March, the Progressive Party (SNS) convincingly won Serbia’s general election and its leader Aleksandar Vucic became the prime minister. With a chequered track record on press freedom, both as deputy prime minister in the previous government and as Slobodan Milosevic’s information minister, Index wondered at the time what impact his new role may have on Serbia’s media. Six months on, what is happening with Utisak Nedelje is just the latest addition to a worrying pattern.

It did not take long for claims of censorship to be levelled at the Vucic government. In May, Serbia and surrounding countries were hit by devastating floods. Authorities imposed a temporary state of emergency, which gave them the power to detain people for “inciting panic”. Meanwhile, online criticism of the government’s handling of the crisis was targeted. Critical articles and blogs were removed, and whole websites, including the independent news outlet Pescanik, were blocked and subjected to DDoS attacks. While it is unconfirmed who exactly was behind these incidents, they already then constituted a “worrying trend”, according to the Organisation for Cooperation and Security in Europe (OSCE).

Index has tracked the media freedom situation in Serbia since the early days of the current government. There have been reports of a journalist being interrogated by police for sharing a Facebook post, as well as physical and verbal attacks — often with impunity. But indirect control of media, smear campaigns and other methods of covert “soft censorship” also pose a serious challenge to Serbian press freedom. “Milošević never muzzled the media this perfidiously. His methods were far less sophisticated and everything was out in the open,” said Beckovic. And it seems her colleagues agree that censorship is prevalent. Ninety per cent of journalists responding to a recent survey said censorship and self-censorship does exist in Serbian media, while 73% and 95%, respectively, said the media does not report objectively and critically.

The public dispute between authorities and the Balkan Investigative Journalism Network (Birn) is one example. The group reported that the government paid significantly more than partner Etihad Airways for a nearly equal stake in new company Air Serbia. Vucic denied the story, saying it was based on an unused draft version of the contract. Days later, pro-government newspaper Informer published an article accusing journalists from Birn and Serbia’s Centre for Investigative Journalism (Cins) of stalking and spying on Vucic. Birn has called this a “campaign to discredit” their work.

“I have the impression that the situation is getting worse,” Mehmet Koksal from the European Federation of Journalists (EFJ) told Index. He cites recent reports of Serbian politicians allegedly faking academic qualifications. “In those articles you can easily measure the level of tolerance from the government to independent media owners,” he explains. He says some newspaper that pushed the story were accused in pro-government outlets of carrying out propaganda for foreign countries. “This is the kind of conspiracy theory that we used to see from different countries.” Pescanik was again brought down by DDoS attacks for reporting the story.

Recent amendments to the country’s media laws will see the state withdraw from nearly all media funding by July 2015. The move has been welcomed by many, but as think tank Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso points out, this alone will have limited impact: “Private tabloids have been for some time the main supporters of the government, and influence is exerted indirectly, mostly through the advertising market.”

Serbia has also adopted a new labour law which was heavily opposed by trade unions. Koksal claims that union leaders have faced media attacks and smear campaigns. If certain media groups or owners have an interest developing good relationships with the Serbian government, he explains, you can “easily understand why they are doing the dirty job” of attacking opposition. But finding out who exactly funds which outlet is not always easy, as bids to increase transparency of ownership has been met with resistance from private media.

After the elections, Index spoke to Lily Lynch, the founder and editor of the English-language online magazine The Balkanist, which used to be based in Belgrade. She recently decided to leave Serbia due to the pressure she has faced as an independent journalists.

“I was pessimistic about the potential for the media situation in Serbia to worsen when the new government, led by Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic, came to power in March. But I think the mask has slipped much faster than any of us expected,” she tells Index.

Lynch also believes international actors have a role to play in the worsening levels of press freedom in Serbia, explaining how the US embassy in Belgrade earlier this year told her to leave the country until after the election. “It seems the US embassy thought it was probably a better idea if I was gone because we were critical of the Vucic regime, which they supported pretty unambiguously.”

She also argues that international media bears some responsibility. “In the pre-election period, the English-language media was pretty uniform in its portrayal of Vucic as some kind of redemptive success story. There were headlines like ‘From Authoritarian Censor to EU Partner’, or ‘From Nationalist Hawk to Devout Europeanist’,” she says.

“Was it responsible for major, supposedly ‘objective’, well-respected publications to project such an image? I would say no, and it’s something I think we need to look at ourselves.”

Vucic has been widely lauded as a reformer, who has set Serbia firmly on the path to EU accession — the country’s main driver of reforms. In 2015, Serbia will also take over the chairmanship of the OSCE. During that organisation’s ongoing high-level human rights conference, the Serbian delegate said the OSCE region’s freedom of expression and media in will be high on their agenda as chairs. Many would argue they could start the work at home.

Correction 09:34, September 30: An earlier version of the article stated that Mehmet Koksal works for the International Federation of Journalists.

This article was published on Monday September 29 at indexoncensorship.org

Serbia: Protesters opposing Belgrade Pride Parade attack B92 offices

Serbia: Photographer injured by anti-pride parade protesters

Serbia: B92 TV station scrapped well-known political talk show

Serbia: Security officer interfered with journalist during political party rally

Serbia: Journalists from “Juzne vesti” labelled foreign mercenaries

21 Mar 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News and features

(Image: Theo Schneider/Demotix)

Serbia is in the process of forming a new government. Following the Progressive Party ‘s (SNS) landslide victory in Sunday’s elections — securing 48% of the votes and 156 of 250 parliamentary seats — one man in particular holds the keys to the country’s future. Leader Aleksandar Vucic, Deputy Prime Minister in the previous coalition, is dropping the prefix and taking the top spot this time around.

While at 44, he would be a relatively young leader, he has had plenty of experience in high politics. Indeed, back in the 90s, he served as Minister of Information under Slobodan Milosevic. Many people spend their twenties trying figure out what to do with their lives. Vucic, meanwhile, was busy introducing a notoriously hardhanded media law, among other things, introducing fines to punish journalists and banning foreign media. As he now prepares to take office, should Serbia’s press be worried?

On the one hand, Vucic has worked hard to shift his image from hardline nationalist, to pro-EU reformer, his focus firmly fixed on Serbia’s struggling economy. He has gone after some of the country’s biggest financial criminals in a high-profile anti-corruption campaign. He has pushed for normalisation in the strained relationship with Kosovo, to put EU accession on track. On election night, the Foreign Minister of the United Arab Emirates, Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed al Nahyan, could be found celebrating with Vucic at the SNS headquarters. The man who once said that 100 Muslims should be killed for every Serb, is securing loans in the billions from the UAE to help fund ambitious regeneration projects in Belgrade.

Yet, despite this apparent commitment to transparency, and despite claiming freedom of the media as one of his “five priorities” — his own personal regeneration, if you will — big words have not really translated into action when it comes to Serbian press freedom.

The country’s journalists have long been working under less than ideal conditions. From the direct, physical threats suffered under the Milosevic regime, to repressive legislation, free expression has been well and truly chilled. But the biggest challenge today is soft censorship, according to the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN).

“Press freedom in Serbia is mostly endangered by soft censorship meaning that it is mostly endangered by discriminatory and un-transparent allocation of state funding towards media outlets. This money is usually used to reward those who are in favor of the government and to punish those who oppose it. As opposed to direct threats, soft censorship is much harder to detect,” BIRN’s Tanja Maksic told Index.

“In [the] last year and a half of the Vucic and [former Prime Minister] Dacic government, we haven’t witnessed much of the determination to stop this undemocratic practice,” she adds.

Indeed, evidence points to the Prime Minister to-be doing the exact opposite. A recent report analysing election content on TV showed that the Progressive Party, and Vucic specifically, were favoured in the, overall strikingly positive, coverage. And back in February, a video adding satirical subtitles to genuine footage showing Vucic rescuing a boy from a snowstorm, was taken down. The video, originally from public broadcaster RTS, was removed over copyright infringement claims, despite campaigners arguing it did not break copyright laws. Authorities are widely believed to have played a part in the removal. A number of websites that had published it were blocked or attacked from within the country, while individuals behind the sites saw their social media profiles hacked. The claims made in the subtitles — that the whole report was staged to paint Vucic in a favourable light ahead of the elections — might have cut too close to the bone.

Vucic’s alleged control over sections of the Serbian media is perhaps most evident in the case of former Economy Minister Sasa Radulovic. Following his resignation, not long before the eventual collapse of the previous government, he was, without explanation, dumped from a popular TV talk show. The last-minute replacement? Aleksandar Vucic. Radulovic soon tweeted that he couldn’t wait to tune in to the evening’s show “to figure out why I resigned”. He followed this up by publishing an explosive resignation letter, accusing the government, including the anti-corruption crusading deputy prime minister himself, of corruption. He added that he’d been subjected to a “media lynching” by tabloids friendly to the government, that self-censorship is rife in Serbian media and that “news is being smothered”. The letter was covered by state-funded news agency Tanjug, but the report was removed within minutes and only republished following complaints.

Lily Lynch is the co-founder and editor of Balkanist, an independent online magazine covering, as the name suggests, the Balkan region. They have first-hand experience of Serbia’s restrictive media environment, once having their power cut for three days after publishing government leaks. She says Vucic has been “disastrous” for Serbian media, and believes that with his newfound, unchecked power they will see “more censorship”.

“I think that self-censorship will likely get even worse than it already is, as compliance with the status quo is often the only way to keep a job in Serbia,” she explains to Index. “Independent media outlets like Pescanik will be allowed to work because their audience is small and marginal, and their existence actually benefits Vucic because he can cite them as evidence that there is media freedom in Serbia. Meanwhile, the media that the majority of the country reads or watches will continue to depict Vucic as the savior of the nation.”

This depiction seems to have made an impact beyond Serbia’s borders too. Vucic’s pro-EU stance, and especially his perceived pragmatism regarding Kosovo, has boosted his international profile. He’s been labelled “the man bringing Belgrade in from the cold”, and American ambassador Michael Kirby has even praised Serbia’s media freedom.

It is, however, also worth noting certain cracks in this image within Serbia. The turnout figures of 53.2% — following the downward trend of previous elections — would suggest the adulation among the population is not as widespread as on first glance. The Facebook group “I did not vote for Vucic”, set up on election day, with its some 2,400 likes and counting, might point to the same.

Tanja Maksic says the real test for the Vucic government will come with adoption of much needed laws prescribing stricter control of media funding from public budget. If these are passed and implemented it “will be a clear demonstration of a new political will to pass the reforms in media sector,” she adds.

Lynch is not optimistic. She says there is a real danger Serbia could go the way of Hungary, a country that under the leadership of Victor Orban has witnessed the state of media freedom nosedive. She is not the only one to make the link. A recent Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty asks if Serbia “is headed for Orbanization”?

“Vucic has used the media as mouthpieces to denounce opponents, smearing them and accusing them of crimes without evidence. I definitely think this will continue. Others say “everything is up to Vucic now, he has no one to excuses anymore” but he has attained this level of power and will not let it go so easily. Anything that goes wrong will be the fault of some minister or other, who will be sacked and humiliated in the press so that Vucic is not viewed as responsible in the eyes of the public,” Lynch says.

“Vucic’s arrests and “anti-crime crusade” has made many public persons, including journalists, very afraid.”

This article was posted on 21 March 2014 at indexoncensorship.org