Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Yeni Bir Şarkı Söylemek Lazım, Video, 2016, Işıl Eğrikavuk

Asena Günal is the program coordinator of Depo which is a center for arts and culture at Tophane, Istanbul. She is one of the co-founders of Siyah Bant, a research platform that documents censorship in the arts in Turkey.

“Is it just me? I don’t think so, but these days I’m in a state where I don’t know what to hold on to, what to do. I push myself to continue my work. Should I continue with art, or should I channel myself to more urgent things; that’s how suffocated I feel,” Hale Tenger, a prominent contemporary artist from Turkey, said in a roundtable discussion published in the Istanbul Art News.1 This pessimism reflects the general mood of artists and many other intellectuals in Turkey, a country that has experienced incidents so numerous in the past year that they could fill decades.

Since July 2015, almost 300 people have been killed and thousands wounded in various attacks by IS and the Kurdistan Freedom Eagles (TAK). After the elections in June 2015, in which the Kurdish party passed the 10% threshold and AKP lost its single party position, president Erdoğan pushed for another election. In November 2015, the AKP won the election and ended the peace process with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The government put severe limitations on the Kurdish and pro-peace opposition. A total of 2,212 academics, who signed a petition to condemn the state violence in the southeast of Turkey, have been targeted by Erdoğan, received threats, have been faced with criminal and disciplinary investigations, and four of them were detained and jailed for about a month. A growing number of academics have been dismissed or suspended, some were forced to resign and had to leave the country. Almost two thousand lawsuits have been filed against people alleged to have insulted the president online or offline.2

In January 2016, two members of the art community were arrested and then sued for participating in the peaceful demonstration “I am Walking for Peace” in Diyarbakır. The march was organised to protest state violence in the Kurdish region and ask for the restarting of the peace process. Artists Pınar Öğrenci and Atalay Yeni were arrested and then released conditionally. Their court cases still continue.

The impact of the recommencement of the war has made itself felt in various fields and ways. The cancellation of the exhibition “Post-Peace” in February 2016 shows the difficulty of expressing critical views on state policies. The exhibition curated by an Amsterdam-based curator Katia Krupennikova was cancelled by the institution Aksanat just five days before the opening, with the director citing the rising tension and the mourning after another bombing in Turkey as the reason. Given that other events went on as scheduled, many thought one of the video works in the exhibition, critical of the dirty war policies of the Turkish state against the Kurdish guerilla was considered risky by Aksanat.3 This was one of the incidents in which the state itself did not act, and actors in the artistic community took on this role. It created a discussion in the art scene about how to struggle in times of repression.4

Ayhan ve ben (Ayhan and me) from belit on Vimeo.

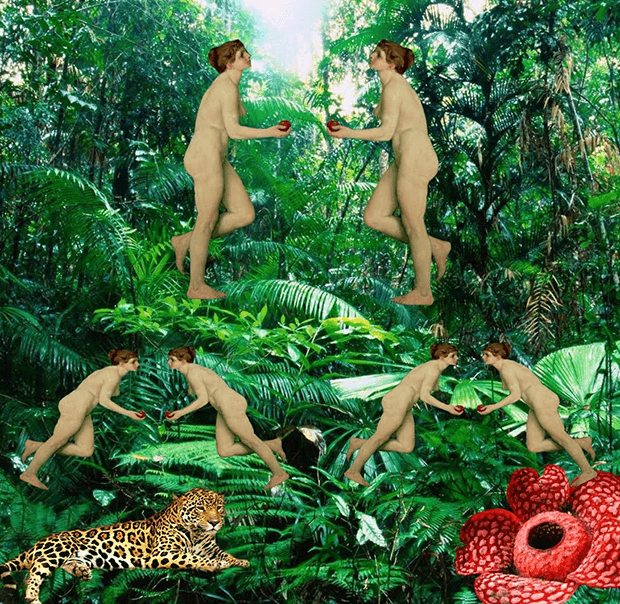

In April 2016, the screen of the public art project YAMA on a hotel roof was shut down by the Istanbul municipality on the basis of an anonymous complaint, claiming that the work of artist Işıl Eğrikavuk, a video animation, projecting the slogan “Finish up your apple, Eve!”, insulted religious sensibilities. When pressed, the municipality cited “visual pollution” as the reason for discontinuing the screening. This turn illustrates a strategy by the national and local government to legitimise their acts of censorship as purely procedural and administrative actions. After Eğrikavuk made a statement, YAMA’s curator Övül Durmuşoğlu declared the project’s support for the artist. Durmuşoğlu organised a meeting to discuss the case and invited Egrikavuk, legal consultants and people from the art scene. In the following days, Eğrikavuk did a performance based on this restraint. Both the meeting and the performance attracted a wide audience.

Even before the coup attempt of 15 July, there was such an atmosphere where people were worried about terrorist attacks, human rights violations, and limitations on freedom of expression. The coup attempt left 246 citizens and 24 coup planners dead and a nation deeply traumatised. The Gülen movement is accused of being behind the last coup attempt. The coup attempt was followed by a State of Emergency which allowed the cabinet under the chairmanship of the president to issue decrees that have the force of law.5 Unsurprisingly, Erdoğan has been using the attempt as an opportunity to eliminate critical voices.

In the five days between the coup attempt and the declaration of State of Emergency on 20 July, many festivals, biennials and concerts were postponed or cancelled by their organisers. The Sinop Biennial (Sinopale) was postponed “due to recent events in Turkey”, the One Love Festival was cancelled “due to availability problems on the schedules of artists and groups”, many concerts of the Istanbul Jazz festival including a performance by Joan Baez was cancelled6, Muse cancelled its concert“due to recent capricious events” and Skunk Anansie did the same “in light of the recent extraordinary events”. One issue of the satirical magazine Leman was banned as it suggested that both soldiers and civilians involved in the country’s recent unsuccessful coup were pawns in a larger game.

After the coup attempt, Erdoğan called the people to “Democracy Watch”-meetings. The biggest and final meeting, was the one at Yenikapı on 7 August 2016.7 Erdoğan invited popular figures, like singers, actors, and actresses to join the meeting. Pop singer Sıla announced on social media that although she was against the coup she would not be part of such a “show” and would not participate in the big meeting in Yenikapı. Sıla was the only figure brave enough to make such a declaration and not step back. But this resulted in the cancellation of her concerts in five different cities. Many people supported her by sharing her music videos and their own photos with an album of Sıla online.

Theatre actor Genco Erkal’s company “Dostlar Tiyatrosu” was banned from performing a play based on the writings of Turkish communist poet Nazim Hikmet and Bertolt Brecht. It was going to be performed in the garden of Kadıköy High School but the school cancelled the contract due to security reasons. It was obvious that security was not the issue and the school was under pressure from the Ministry of Education because of Genco Erkal’s critical stance. After protests of the theater company and members of the main opposition party (CHP), who brought the case to the Parliament, the Governorate lifted the ban.

Municipal and state theaters have been under a tight grip for some time and there have been ongoing discussions about privatisation of these institutions. The State of Emergency not only aimed at Gülenists who were accused of being part of the planning of the coup but also many artists with apparent oppositional stance were affected. On 1 August, the Istanbul Municipality fired 20 people, including director Ragıp Yavuz, actor Kemal Kocatürk, and actress Sevinç Erbulak from the Municipal Theatre based on the decree law number 667 which was announced after the declaration of the State of Emergency. They were not even granted an explanation for why they lost their jobs, but only received a vague reference to supposedly having failed “the evaluation criteria”8. Obviously, they did not have any connection with coup plotters. Eleven of them have been reinstated in their former positions.

Besides bans and purges, the State of Emergency has enabled the government to re-regulate the organisational structure of the state. A new law that would bring the privatisation of State Theatre, State Opera and Ballet, Atatürk Cultural Center, and Turkish Historical Society was discussed in Parliament. Many people from the field of theatre, opera and ballet expressed their concern that the State of Emergency might be utilised to bring privatisation after years of discussion on instating an independent arts council.

It is now common for the members of the ruling party to randomly target artists, writers, or academics in order to intimidate wider cultural milieu. A recent example is from the field of contemporary arts: In September 2016, an AKP MP Bülent Turan targeted the curator of the Çanakkale Biennial Beral Madra and called on the Çanakkale Municipality (run by CHP) not to work with her. The accusation was being critical of Erdoğan, and hence -so the argument went further- being “pro-coup”. Madra became a target because of her critical tweets and Facebook posts. Being critical of Erdoğan has long been risky but now it is associated with being “pro-coup”. Beral Madra withdrew from her position as to not put the Biennial at risk. Then the organising institution announced that the biennial would be cancelled altogether. They were saddened by the current political atmosphere, which did not place art as a primary point of concern. The CHP-run municipality and many people from the art scene expressed concern over the cancellation, highlighting instead the potential of art to counter the authoritarian discourse of AKP and expressing their wishes for the Biennial to go ahead as planned.

Despite this rising authoritarianism and the pessimistic atmosphere, Turkey’s culture and art scene will continue its struggle. Last week there were many openings in different galleries around Istanbul and almost all of them were crowded. People from the art scene are in need of each other more than ever, aware of the vital importance of solidarity in times of hardship. Film, music, dance and performance festivals started to take place, their posters filling the streets. So I would like to finish with another quote from the same issue of Istanbul Art News, by Deniz Artun,9 the director of Ankara Galeri Nev, as I tend to share its optimistic sentiment: “I guess that art history has shown us time and again just how deep the traces left by exhibitions, artworks, artists emerging with ‘pertinacity’ will be; not those amidst freedoms and prosperity, but those coming forth among fears and uncertainties that are burdensome for all of us.”

More about the arts in Turkey:

Belit Sağ: Refusing to accept Turkey’s silencing of artistic expression

Life is getting harder for objective journalists in Turkey, says cartoonist sued by Erdogan

Turkey: Artistic freedom and censorship

Turkey: Artists engaged in Kurdish rights struggle face limits on free expression