7 Jan 2014 | Egypt, News and features

Head of the April 6 Youth Movement Ahmed Maher and two other activists were in December sentenced to three years in prison, among other things for “staging a protest rally without prior permission from the authorities” (Image: Roger Anis/Demotix)

After officially classifying the Muslim Brotherhood as a “terrorist organisation”, Egypt’s military-backed regime has in recent days, widened its crackdown on supporters of the Islamist group.

But the Egyptian authorities’ heavy clampdown on dissent has also increasingly targeted non-Islamists — including secular revolutionary activists who took part in the June 30 military-backed protests that toppled Islamist President Mohamed Morsi.

On Friday, seventeen Islamist “anti-coup” protesters were killed and scores of others were injured in clashes with security forces nationwide, Egypt’s Health Ministry said. Meanwhile, three journalists working for the Al Jazeera English channel remain in custody pending investigations on charges of “being linked to a terrorist organisation and spreading false news that harms national security.” Egyptian officials have accused the Qatari-based Al Jazeera network of backing the Muslim Brotherhood.

Three prominent revolutionary activists also languish behind bars after being handed down three-year jail sentences in December. Ahmed Maher, Founder/Head of the April 6 Youth Movement (one of the two main groups that planned and organised the 2011 mass uprising), Mohamed Adel, a member of the April 6 group and activist Ahmed Douma have been accused of “thuggery, assaulting police officers and staging a protest rally without prior permission from the authorities.” In November, the Egyptian government passed a controversial law criminalising protests without permission from the Interior Ministry.

The activists are on hunger strike to protest their imprisonment on what they — and various rights organisations — have described as “politically-motivated” charges. They are also protesting the harsh prison conditions and their “maltreatment” at the hands of prison guards and inmates.

On Saturday, the Free Alaa Facebook group slammed the “rights abuses” the detainees face at Torah high security prison where they are being held. According to a statement posted on the group’s Facebook page, the detainees are being held in solitary confinement for 22 hours a day and are being denied access to all forms of communication including with family members. “It has become clear to the detainees and their families that the Interior Ministry is not solely responsible for the rights violations. The Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Prison Administration are also implicated,” the statement said.

Other activists too are paying a high price for their criticism of the regime. Political activist Alaa Abdel Fattah, a symbol of the January 2011 Revolution, his sister Mona Seif (Founder of the No To Military Trials movement) and ten other defendants on Sunday received a one year suspended jail sentence for allegedly “attacking the campaign headquarters of former presidential candidate Ahmed Shafik in May 2012”. Both Alaa and Mona have denied the allegation. Before appearing in court on Sunday, Seif told the independent Al Shorouk newspaper that there was no evidence to incriminate her — or her brother — in the case. Alaa will remain in jail on other charges including for allegedly “organising and taking part in an unauthorised November anti-military protest rally”. Alaa has denied organising the protest. His imprisonment, meanwhile, has provoked an outcry from rights campaigners who believe the activist has been jailed “for his oft-scathing criticism of the abuses committed by the security forces.”

Meanwhile, other revolutionary activists have decried what they describe as “efforts by the current regime to defame them”. Asmaa Mahfouz, an internet activist who played a key role in the mass mobilisation of Egyptians that led to the January 2011 Revolution and former MP and activist Mustafa El Naggar have filed lawsuits against TV talk show host Abdel Rahim Ali (widely believed to have close links with the country’s various security agencies) after he aired what he claimed were taped telephone conversations by the activists. The leaked conversations, broadcast last week on TV show “The Black Box” on the privately-owned satellite channel Al Qahira al Nas, provoked an outcry from Egyptian rights organisations. A joint statement released by several rights groups denounced the leakages as “a breach of privacy and a serious violation of basic individual and civil liberties.” The statement also called on the authorities to bring those responsible for eavesdropping, taping and broadcasting the telephone conversations to justice. Ali has remained defiant however, subsequently vowing to air many more taped telephone calls which he claimed would “expose those implicated in a foreign plot to destroy the country.”

The leaked telephone conversations focused on secret documents seized by the activists in question on March 4, 2011. That was the day hundreds of protesters stormed the offices of the much-detested State Security Service, the SSS, to acquire documents they hoped “would expose the crimes of the security agency against Egyptians during the Mubarak era”. The SSS was dismantled shortly after the raids and was renamed “National Security.” The military rulers who replaced Hosni Mubarak immediately after the January 2011 mass uprising, had vowed at the time that the new security authority would be solely concerned with dealing with “national security issues” and would not repeat the practices of the old SSS (including mass surveillance and spying on citizens). As a result of the recently televised leaks, several “private citizens” have filed lawsuits against Mahfouz and Israa Abdel Fattah (another prominent internet activist and former member of the April Six group) accusing them of “inciting the raids on the SSS Headquarters”.

In comments posted on his Facebook page, former lawmaker El Naggar said the leaked conversations were a form of revenge by the state against revolutionary activists. He also described them as a means of “character assassination to defame him and other political opponents of the military-backed regime.”

Meanwhile, an online statement released on January 3 by Amnesty International urged the authorities in Egypt to “halt their crackdown on vocal critics of the regime — including the use of politically-motivated trials to punish dissidents.”

One activist who chose to remain anonymous has best described the heavy-handed, repressive measures used by the state to intimidate and silence critics as “counter-revolutionary practices” which he said were designed “to crush dissent and wipe out all traces of the January 2011 Revolution.”

“But the critics will neither be intimidated nor silenced,” he said. He added that “the current regime tends to forget that the fear is gone… There is no going back to pre-January 2011.”

This article was published on 7 Jan 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

12 Dec 2013 | Egypt, Middle East and North Africa, News and features

An Egyptian appeals court on Saturday revoked harsh 11-year jail sentences handed down in November to 14 girls and women for staging a protest in Alexandria demanding the reinstatement of toppled President Mohamed Morsi. The 14 defendants were given suspended sentences of one year in prison each after the earlier verdicts provoked a public outcry and drew fierce criticism from local and international rights groups.

An Egyptian appeals court on Saturday revoked harsh 11-year jail sentences handed down in November to 14 girls and women for staging a protest in Alexandria demanding the reinstatement of toppled President Mohamed Morsi. The 14 defendants were given suspended sentences of one year in prison each after the earlier verdicts provoked a public outcry and drew fierce criticism from local and international rights groups.

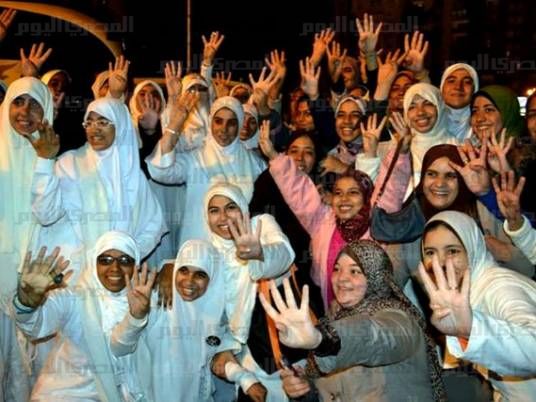

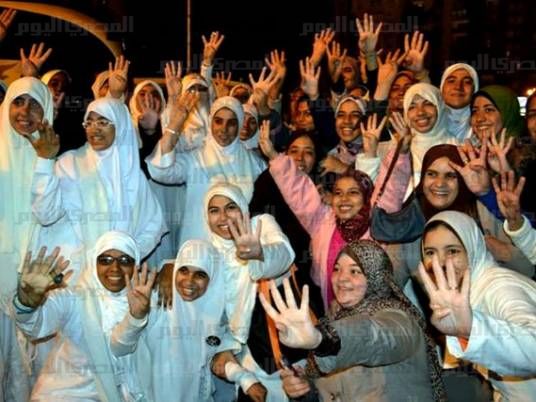

Seven minors — aged 15 and 16 — who had also taken part in the Alexandria 31 October protest were acquitted by the court but are to remain on probation for the next three months.The young defendants who were released on Saturday after a month in custody, had previously been ordered detained in a juvenile centre until they turned 18 . The girls are members of the so-called “7am movement” that had recurrently held early morning “anti coup” protests outside a school in the Mediterranean port city.

All 21 defendants had been charged with ” thuggery, vandalism , illegal assembly and use of weapons” — charges that rights groups insist were “politically motivated”. In a statement condemning the November verdicts, Amnesty International described the girls as “prisoners of conscience” and said their detention reflects the Egyptian authorities determination to punish dissent. Human Rights Watch , HRW, meanwhile said “the court had violated the right to free trial as witnesses were barred from testifying in the girls’ defence.” Little evidence was provided for the charges the girls faced”, HRW added.

Egyptian rights groups also expressed concern over the jail terms and agreed that the defendants faced “trumped up charges”

“Such verdicts raise doubts about the independence of the judiciary in Egypt and signal a return to the Mubarak era when the courts were often used as a political tool against the opposition,”the Cairo-based Arab Network for Human Rights Information, ANHRI, said in a statement released after the verdicts were announced by a Misdemeanour Court. In a statement issued on the Muslim Brotherhood’s official website Ikhwanweb , the Freedom and Justice Party, the political arm of the Islamist group also denounced “the unjust “verdicts sentencing the girls to long jail terms for what the FJP said were “peaceful protests”.

Images of the young defendants clad in white prison garments and headscarves were widely circulated on social media networks, fuelling the anger of Egyptian activists–including many who participated in the June 30 uprising demanding that President Morsi step down. In a message posted on Twitter on 27 November (the day the verdicts were announced), blogger Zeinobia stated “Today Egypt jailed 14 girls for holding balloons at a protest!”.

Other activists expressed their dismay saying they believe the convictions are “part of a nationwide crackdown on Muslim Brotherhood supporters and efforts by the interim government to silence dissent.” They drew comparisons between police officers accused of killing protesters escaping justice while the girls were convicted for exercising their right to protest peacefully. In a Twitter post, rights lawyer and Head of the AHRNI Gamal Eid wrote ” the same judiciary that released Wael El-Komi, an Alexandria police officer accused of killing no fewer than 37 protesters, has sentenced 14 girls to 11 years in prison.”

“The state where there is respect for rule of law welcomes you!” he sarcastically added .

Egyptian authorities insists they are “waging a war against terrorists seeking to destabilize the country”. Thousands of Islamists have been detained since Morsi’s overthrow by military supported protests on 3 July and hundreds of pro-Morsi protesters were killed when security forces dispersed two Cairo sit-ins in mid-August, in what rights advocates have described as “the worst massacre in modern Egyptian history.”

In recent weeks the military-backed government has widened its crackdown, detaining dozens of secular pro-democracy activists who have helped the military consolidate its power by participating in the June 30 uprising against the previous Islamist government. Prominent political activists Alaa Abdel Fattah, Ahmed Maher and Ahmed Douma were among protesters detained two weeks ago for violating a new law regulating protests. They face investigations and have been referred to military courts on charges of allegedly “inciting protests, thuggery and resisting security forces”.

The excessive use of force by security forces in dispersing the recent protests and the harsh verdicts for the Alexandria girls signal a return of rights violations reminiscent of the Mubarak era, serving as a warning message that the authorities will stop at nothing to silence dissent.

This article was posted on 12 Dec 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

18 Nov 2013 | Egypt, News and features, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture

Supporters of Egypt’s ousted President Mohammed Morsi in Helwan District raise his poster and their hands with four raised fingers, which has become a symbol of the Rabaah al-Adawiya mosque. (Nameer Galal / Demotix)

Public service messages on Egyptian radio stations candidly tell listeners that a new constitution currently being drafted by a fifty-member panel “won’t be the best that the country has had”. Listeners are assured however, that the new charter will not be Egypt’s last.

“Regardless of whether you approve or disapprove of the new charter, you must vote in the popular referendum on the document,”exhorts the radio ad. “This will send a message to the world that Egyptians are united.”

The radio spots serve as a warning to the public against raising their expectations too high for the new constitution which –if endorsed in a national referendum slated for January 2014–will replace the country’s first post-revolution constitution drafted under Muslim Brotherhood rule. The 2012 constitution’ crafted by an Islamist-dominated panel was suspended on July 3 — the day Islamist President Mohamed Morsi was toppled by military-backed mass protests. Critics blame the “divisive, Islamist-tinged constitution” for Morsi’s political isolation while he was still in office and say that it ultimately led to his downfall. The 2012 charter– and a decree issued by the now-deposed president giving himself extra-judicial powers –sparked violent protests outside the presidential palace last December in which around a dozen people were killed. The toppled president is now facing trial for allegedly inciting the killing of protesters during what has since come to be known as the “Ittihadeya violence”.

A fifty-member constituent assembly made up mostly of leftists and liberal politicians, who were hand picked by the interim government, is currently working on amending the 2012 disputed charter. The assembly has been given a sixty day mandate, which expires on December 3, to complete the seemingly Herculean task. Democracy advocates had hoped the revised document would be a vast improvement to the one liberals had complained “strengthened the role of Islamic law, gave the military extensive powers and undermined the rights of minorities and women.” But as the deadline draws near for submitting the draft document to interim president Adly Mansour, rights campaigners say their hopes for a more liberal constitution that meets the aspirations of Egypt’s revolutionaries have been all but dashed . They complain that “the draft charter grants the military even greater powers and preserves the Islamic law provisions while also falling short of protecting the rights of women and workers .”

Revolutionary activists are particularly enraged by a provision that would grant the military the power to try civilians in secret military courts. Senior army officials have defended the clause saying it is “necessary in light of the surge in Islamist militant attacks against security and military forces in the Sinai and elsewhere in the country since Morsi’s ouster.” Rights advocates meanwhile argue that such trials are “hasty and are known to deliver disproportionately harsh sentences.” Hassiba Sahraoui , Amnesty International’s Deputy Director for the Middle East and North Africa has denounced Egyptian military tribunals as being “notoriously unfair.” Egyptian journalist Ahmed Abu Draa , the Sinai correspondent for the independent Al Masry El Yom Newspaper was detained by the military last September and faced a military tribunal on charges of “spreading false news about the military”. In a statement calling for his release, Sahraoui reminded Egyptian authorities that “trying civilians in military courts flouts international standards.” She also denounced the decision to try Abu Draa in a military court as “a serious blow to press freedom and human rights in Egypt.” While Abu Draa was handed a six month suspended jail sentence in October,anyone who challenges or “insults the military” risks suffering a similar fate.

While the previous constitution had given the military the discretion to indict civilians for “crimes that harm the armed forces,” the revised document allows the army to indict anyone “for crimes in which officers are involved.” The “No To Military Trials For Civilians group”–a grassroots movement working to end the practice, has in recent days threatened to reject the draft charter if the provision remains unchanged.

“It is clear that the military wants to maintain its privileges including the broad discretion to punish and try people as they choose,” Heba Morayef, Human Rights Watch Egypt Director, told the Washington Post earlier this month.

A brutal security crackdown on members and supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood — including the detention of more than 2000 members of the Islamist group, ill-treatment of political detainees and the killing of around 1000 people since Morsi’s ouster– signals continued impunity for the military and the police in Egypt, Morayef lamented.

Role of Islam

Religion has always played an important role in Egypt’s conservative, patriarchal society. Prior to the January 2011 uprising, Egypt could neither be described as a “religious” state nor as a “secular” state (in the Western sense of the word). While the country was not ruled by “religious authority, practically every aspect of Egyptian life was governed by religion. Under Muslim Brotherhood rule, Egypt’s liberals and Christians had feared the country was headed on the path of even greater Islamisation. Morsi’s ouster, however, revived the hopes of some of the revolutionary and liberal groups for the creation of the “secular, civil state” that revolutionary activists had called for during the 2011 mass uprising that toppled former President Hosni Mubarak. It is now almost certain that those groups are headed for disappointment.

Right from the start of the constitution amendment process, it became clear that Article 2 would remain unchallenged. The article –adopted from the two previous constitutions– states that “the principles of Islamic Law (Sharia) are the principle source of legislation in the country” and that “Islam is the religion of the state.” Another provision meanwhile, stipulates that Egyptian Christians and Jews should refer to their own religious laws on personal status issues. Unlike those two provisions which are supported by a majority of the assembly members, Article 219 –which defines Islamic Law based on Sunni Muslim jurisprudence — has been a bone of contention, sparking heated debate among the members. The three Christian members on the panel this week threatened to walk out if the controversial article was not removed. They fear the provision which allows for stricter interpretations of Islam could undermine the rights of Egypt’s minority non-Muslim population (including Christians who make up an estimated 10 to 12 percent of the population). Bassam al-Zarqa, the sole Salafi member on the panel insists however that the provision should remain in the new charter.

Since the military takeover of the country a little over four months ago, Egypt has witnessed a surge in church attacks while hundreds of Christians have been forced to flee their homes in search of less hostile environments.

While the panel has voted separately on each of the amended articles, it has postponed discussions on the contentious issues until the end of the month to allow tensions to ease. It remains to be seen however, whether the wide gap in the members’ perceptions of the role of Islam in the “new Egypt” can be bridged .

Women’s Rights

Rights advocates have also expressed concern that the draft charter may not match expectations for greater rights for women. Calls by women’s rights groups for restoration of a quota system that would ensure fair representation of women and Christians in parliament have so far fallen on deaf ears. Last Wednesday, dozens of activists staged a protest rally outside the Shura Council headquarters in Cairo demanding the re-introduction of the women’s quota without which they fear women will be grossly under-represented in the next parliament.

“The panel has announced it would retain the obligatory 50 percent parliamentary representation of workers and peasants from earlier constitutions, why then doesn’t it re-introduce the quota system so that women too can guarantee a fairer representation in the People’s Assembly?” asked Mona Qorashy, a feminist who participated in Wednesday’s rally.

Low female representation in parliament and a surge in sexual violence against women have pushed Egypt to the bottom of the Arab region for women’s rights. A recent poll by the Thomson Reuters Foundation on the treatment of women in 22 Arab countries has labelled Egypt “the worst Arab country for women” below Saudi Arabia and Iraq — two countries known to have an exceptionally poor human rights record.

Workers’ Rights

Workers too are unhappy about their rights in the draft constitution. In comments to the semi-official Al Ahram newspaper, Kamal Abbas, a rights activist and Coordinator of the Centre for Trade Union and Workers Services described the draft document as “labour-unfriendly.” He cites Article 14 as one of the reasons for his conviction. “The article states that ‘peaceful industrial actions like strikes and sit-ins are inherent labour rights’ but then goes on to empower legislators to regulate such action,” he complained.

Representatives of the newly formed trade unions are absent from the constituent committee, he lamented, adding that “the sole labour representative on the panel is a member of the government-controlled Egyptian Trade Union Federation–an ardent opponent of the ongoing labour strikes.”

As panel members race against time to meet the December 3 deadline for submitting the draft document to the President , public debates on the document are taking place in parallel outside the confines of the Shura Council premises. Egyptians who have become increasingly politicized since the 2011 uprising, are adamant to take part in the discussions that will shape their future for years to come. “We cannot afford to wait for the referendum to express our views on the constitution. Now is the time to pile pressure on the politicians. After all, it is our destiny –and that of our children– which is at stake,” said Somaya Saeed, a veiled housewife who was at the women’s protest last Wednesday. She pointed to a placard raised by another protester and read the words out loud: “Women are capable of effecting change. Where are the women in the new constitution?” With only five women on the constituent panel, it is not surprising that the rights of women are being overlooked.

This article was originally published on 18 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Oct 2013 | Egypt, News and features, Religion and Culture

After months away from the small screen, TV satirist Bassem Youssef is back on the air but it is uncertain how long he’ll stay. After a four month absence (Youssef’s disappearance coincided with the overthrow of Egypt’s first democratically-elected President by a military coup) he returned to the airwaves last Friday with a new episode of his weekly TV show Al Bernameg (The Programme). The episode sparked a new wave of controversy, reflecting the deepening divisions in Egyptian society.

Just 48 hours after the show was broadcast, the Public Prosecutor ordered an investigation into a legal complaint against Youssef, one of several filed by citizens angered by his mockery of the military chief. Others were upset by jibes he made at the former ruling Islamists. Youssef has been accused of “inciting chaos, insulting the military and being a threat to national security.”

Youssef is no stranger to controversy. He caused a stir when he mocked the now deposed Islamist President Mohamed Morsi on his show, broadcast on the independent channel CBC. At the time, several lawsuits were filed against him by conservative Islamist lawyers who accused him of “insulting Islam and the President” and Youssef consequently faced a probe by the Public Prosecutor. The charges against him were dropped several months later however. President Morsi was careful to distance himself from the legal complaints filed against Youssef, insisting that he “recognised the right to freedom of speech.” While the lawsuits did little to harm Youssef (in fact, they actually contributed to boosting his popularity and improving the ratings of the show), they did damage the image of the ousted President, who was harshly criticised for “intimidating and muzzling the press.” A couple of months before his removal from office, Morsi was accused by critics of “following in the footsteps of authoritarian Hosni Mubarak and of using repressive tactics to silence dissent.”

Now, under the new military-backed interim government, Youssef finds himself in hot water again. This time the TV comedian, known as Egypt’s Jon Stewart, is in trouble for poking fun at leaked comments by the Defence Minister, General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, suggesting that the General would “find partners in the local media willing to collaborate to polish the image of the military.” In recent months, Youssef has maintained an objective and neutral position vis a vis the events unfolding in Egypt. In his articles published in the privately-owned Al Shorouk daily, he has expressed concern over the brutal security crackdown to disperse two pro-Morsi sit ins in Cairo on August 14, in which hundreds of Muslim Brotherhood supporters died. But he has also been careful to criticise the attacks on churches (often blamed on Islamists) following the coup.

Friday’s episode, which marked the start of a new season for the show, focused in part on the blind idolisation of al-Sisi by many Egyptians since the coup. The word coup was never once mentioned on the programme. In one scene, Youssef is seen putting his hand over the mouth of one of his assistants in an attempt to silence him as he utters the now-taboo word. In recent weeks, calls have grown louder for the General to run in the country’s next presidential election and a group of adoring fans has even begun collecting signatures for his candidacy.

The fact that Youssef is being prosecuted again after what many Egyptians consider was a “second revolution” signals that the June 30 revolt that ousted the Islamist President has failed to usher in a new era of greater press freedom .The lawsuits serve as a chilling reminder of the dangerous polarisation in the country, which some analysts warn may push it into civil war and chaos. While Youssef did take part in the June 30 protests that toppled Morsi, he has clearly decided not to take sides in this hostile environment. In an article published days before the show, he noted that many Egyptians advocate for free speech and democracy “as long as it is in their favor” but turn against you the minute your opinions differ from theirs. Aware that his episode had ruffled feathers, he sought to ease tensions with a message on Twitter that reminded his viewers, fans and critics alike, that at the end of the day, this is just “another episode in a TV show.”

This article was originally posted on 30 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

An Egyptian appeals court on Saturday revoked harsh 11-year jail sentences handed down in November to 14 girls and women for staging a protest in Alexandria demanding the reinstatement of toppled President Mohamed Morsi. The 14 defendants were given suspended sentences of one year in prison each after the earlier verdicts provoked a public outcry and drew fierce criticism from local and international rights groups.

An Egyptian appeals court on Saturday revoked harsh 11-year jail sentences handed down in November to 14 girls and women for staging a protest in Alexandria demanding the reinstatement of toppled President Mohamed Morsi. The 14 defendants were given suspended sentences of one year in prison each after the earlier verdicts provoked a public outcry and drew fierce criticism from local and international rights groups.