Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Union Chapel, Islington (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Stand Up For Satire, hosted at the Union Chapel in Islington on Tuesday 4 July, was a night of top comedy in support of Index on Censorship, hosted by Australian stand-up Brendon Burns. The stellar line-up featured comedians Al Murray, Tim Key, Dane Baptiste, Kerry Godliman, Deborah Frances-White, Felicity Ward and Robin Ince, plus a special reading from George Orwell’s Animal Farm by actor and Index patron Simon Callow.

Among the topics poked fun at were North London conformists, the British, the middle class, Brexit, hipsters and your racist nan.

For this special podcast below, Index spoke with Burns, Baptiste, Ince and Murray backstage about the importance of satire and why their craft is uniquely powerful.

Union Chapel, Islington. (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Union Chapel, Islington. (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

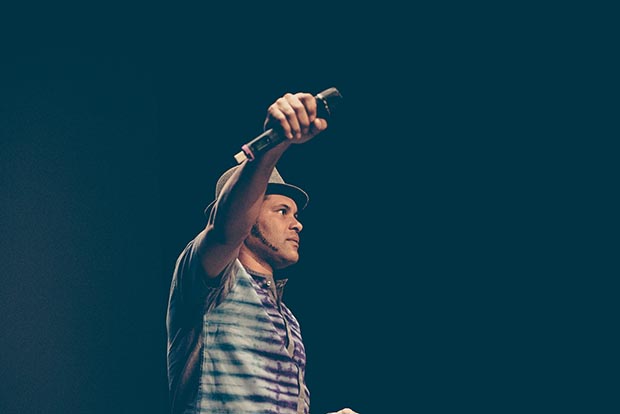

Comedian and host Brendon Burns (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian and host Brendon Burns (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Union Chapel, Islington (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Tim Key (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Tim Key (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Felicity Ward (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Felicity Ward (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Felicity Ward (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Actor Simon Callow (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Dane Baptiste (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Union Chapel, Islington (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Deborah Frances-White (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Deborah Frances-White (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Kerry Godliman (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Kerry Godliman (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Union Chapel, Islington (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Robin Ince (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Al Murray (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Al Murray (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian Al Murray (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

“Censorship is as much with us as it ever was,” said author, lawyer and early Index supporter Louis Blom-Cooper, in a speech to mark the 250th issue of Index on Censorship magazine, during its launch at London’s magCulture on Tuesday 12 July.

The event saw special performances by actor Simon Callow, who read Maya Angelou’s poem Caged Bird, Norwegian singer Moddi, and spoken-word artist Jemima Foxtrot, who had created a poem especially for the occasion.

When the first issue of Index on Censorship magazine was printed in 1972, the world was still in the grip of the Cold War, the internet was embryonic for high-end researchers and Britain had yet to join the European common market.

The next 249 issues chronicled the pressures faced by free speakers and free thinkers all over the world — from Argentina’s Dirty War to the rise of China’s Great Firewall. Against this backdrop of change, Index has remained committed to covering unreported stories and publishing silenced voices.

The event, The Power of Print, was held as a celebration of the magazine’s longevity and constant vigilance, as well as a tribute to all who have shared their stories and struggles.

Rachael Jolley, editor of Index on Censorship magazine, emphasised the importance of magazine culture in our lives today, despite the rise of modern technology. In a short speech she said, “Index is a global magazine read by people all over the world in 172 countries”. She said the global reach has made an impact in promoting the cause of freedom of expression, and reminded those attending of the dangers journalists face worldwide. The latest issue has a special report on the risks of reporting.

“The power of magazines remains as relevant as ever,” added Jeremy Leslie, owner of magCulture, a new specialist magazine shop and a new stockist of the magazine.

Order your full-colour print copy of our journalism in danger magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London, Home in Manchester, Calton Books in Glasgow and News from Nowhere in Liverpool as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.

Favourites from the @Index_Magazine archives –“ Letter to my father”, Ken Wiwa – free to read #Index250 https://t.co/hxAs13KvLS

— SAGE Media & Comm (@SAGEmedia_comm) July 13, 2016

Having a great time celebrating @Index_Magazine 250th issue #Index250 pic.twitter.com/GyaBt3TwZ5

— Alex Smith (@suyinsmith) July 12, 2016

Jeremy Leslie of @magculture, our host tonight, on why print is still so powerful today #index250 pic.twitter.com/k8Z6ylSwhB

— IndexCensorshipMag (@Index_Magazine) July 12, 2016

Wonderful reading of Maya Angelou’s Caged Bird by @Simoncallow, one of our great supporters. Thanks Simon #index250 pic.twitter.com/Pvn8UKibA5

— IndexCensorshipMag (@Index_Magazine) July 12, 2016

A shop dedicated to beautiful magazines! Today with a special display of @Index_Magazine. @magculture#index250pic.twitter.com/FiqSWd2LcF

— Vicky Baker (@vickybaker) July 12, 2016

More from the magazine:

Moddi: Unsongs playlist of the banned, censored and silenced

Marking the 250th issue: Contributors choose favourites from the Index on Censorship archives

Survey: Are ad-blockers killing the media?

War reporter Marie Colvin’s family sues Syria

Podcast: Kenyan journalist forced into hiding after reporting news

Journalists under fire and under pressure: summer magazine 2016

Risky business: Journalists around the world under direct attack

Freedom of Expression Awards 2016 from Index on Censorship on Vimeo.

A female journalist training reporters from within war-torn Syria, and a group busting online censorship in China are among this year’s Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards winners.

The winners, announced on Wednesday evening at a gala ceremony in London, also included a Yemen-based street artist and campaigners from Pakistan battling internet clampdowns.

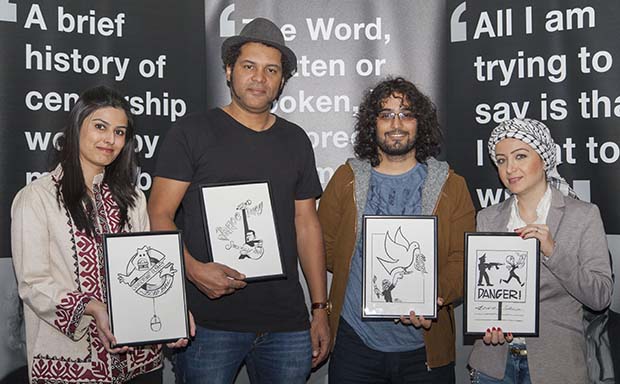

Awards are presented in four categories: arts, journalism, digital activism and campaigning. The winners were: Yemeni street artist Murad Subay (arts), Syrian journalist Zaina Erhaim (journalism), transparency advocates and circumventors of China’s “Great Firewall” GreatFire (digital activism) and the women-led digital rights campaigning group Bolo Bhi (campaigning).

“These winners are free speech heroes who deserve global recognition,” said Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg. “They, like all of those nominated, face huge personal and political hurdles in their fight to ensure that others can express themselves freely.”

Drawn from a shortlist of 20, and more than 400 initial nominations, the winners were presented with their awards at a ceremony at The Unicorn Theatre, London, hosted by comedian Shazia Mirza. Music was provided by Serge Bambara – aka “Smockey” – a musician from Burkina Faso who won the inaugural Music in Exile Fellowship, presented in conjunction with the makers of award-winning documentary They Will Have to Kill Us First: Malian Music in Exile. The award was presented by Martyn Ware, founder member of the Human League and Heaven 17.

#IndexAwards2016: Shazia Mirza, Farieha Aziz, Murad Subay, Jake Hanrahan, Zaina Erhaim, Nadia Latif, Jodie Ginsberg, Bindi Karia, Anthony House, James Rhodes, Martyn Ware, Kirsty Brimelow, Ziyad Marar (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Actors, writers and musicians were among those celebrating with the winners. The guest list included actor Simon Callow, academic Kunle Olulode, and journalists Lindsey Hilsum, Matthew Parris and David Aaronovitch.

Winners were presented with a framed caricature of themselves created by Malaysian cartoonist Zulkiflee Anwar Haque (“Zunar”), who faces 43 years in jail on sedition charges for his cartoons lampooning the country’s prime minister and his wife.

Each of the award winners becomes part of the second cohort of Freedom of Expression Awards fellows. They join last year’s winners – Safa Al Ahmad (Journalism), Rafael Marques de Morais (Journalism), Amran Abdundi (Campaigning), Tamás Bodoky (Digital activism), Mouad “El Haqed” Belghouat (Arts) – as part of a world-class network of campaigners, activists and artists sharing best practices on tackling censorship threats internationally.

Through the fellowship, Index works with the winners – both during an intensive week in London and the rest of the awarding year – to provide longer term, structured support. The goal is to help winners maximise their impact, broaden their support and ensure they can continue to excel at fighting free expression threats on the ground.

Judges included human rights barrister Kirsty Brimelow QC; Bahraini campaigner Nabeel Rajab, a former Index award winner; pianist James Rhodes, whose own memoir was nearly banned last year; Nobel prize-winning author Wole Soyinka; tech entrepreneur Bindi Karia; and journalist Maria Teresa Ronderos, director of the Open Society Foundation’s independent journalism programme.

Ziyad Marar, global publishing director of Sage Publications, said: “Through working with Index for many years both as publisher of the magazine and sponsors of the awards ceremony, we at Sage are proud to support a truly outstanding organisation as they defend free expression around the world. Our warmest congratulations to everyone recognised tonight for their achievements and the inspiring example they set for us all.”

This is the 16th year of the Freedom of Expression Awards. Former winners include activist Malala Yousafzai, cartoonist Ali Ferzat, journalists Anna Politkovskaya and Fergal Keane, and human rights organisation Bahrain Center for Human Rights.

Winners of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: from left, Farieha Aziz of Bolo Bhi (campaigning), Serge Bambara — aka “Smockey” (Music in Exile), Murad Subay (arts), Zaina Erhaim (journalism). GreatFire (digital activism), not pictured, is an anonymous collective. (Photo: Sean Gallagher for Index on Censorship)

2016 Freedom of Expression Awards: The acceptance speeches

Bolo Bhi: “What’s important is the process, and that we keep at it”

Zaina Erhaim: “I want to give this award to the Syrians who are being terrorised”

GreatFire: “Technology has been used to censor online speech — and to circumvent this censorship”

Murad Subay: “I dedicate this award today to the unknown people who struggle to survive”

Smockey: “The people in Europe don’t know what the governments in Africa do.”

2016 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award winner Zaina Erhaim (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Zulkiflee Anwar Haque, aka “Zunar”, upper right, is saluted by the audience. (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Google’s Anthony House and tech entrepreneur Bindi Karia presented the 2016 Freedom of Expression Digital Activism Award to anonymous tech collective GreatFire (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

2016 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award winner Zaina Erhaim and Jake Hanrahan of Vice News (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Sage’s Ziyad Marar, Fareiah Aziz, director of the 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award Bolo Bhi and human rights barrister at Doughty Street Chambers London Kirsty Brimelow (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Theatre director Nadia Latif, 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award Murad Subay and pianist James Rhodes (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Music in Exile Fellowship Winner Serge Bambara, aka Smockey (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Music in Exile Fellowship Winner Serge Bambara, aka Smockey (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Music in Exile Fellowship Winner Serge Bambara, aka Smockey (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Musician Martyn Ware, founder of The Human League and Heaven 17 (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Pianist James Rhodes and 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award winner Murad Subay (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Farieha Aziz, director of 2016 Freedom of Expression Campaigning Award winner Bolo Bhi (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

2016 Freedom of Expression Journalism Award winner Zaina Erhaim (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Comedian and 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards host Shazia Mirza (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

The 2016 Freedom of Expression Awards gala (Photo: Elina Kansikas for Index on Censorship)

Spring 2016 cover

When I was at drama school in the early 1970s, there was a middle-aged Iranian on the directors’ course called Rokneddin. He’d been ejected from the Shah’s Iran for staging subversive productions. Rokneddin was no political firebrand: he had simply tried to put on Shakespeare’s history plays, which, like all plays in which a king died, were banned in Iran under the Pahlavi dynasty. The plays reminded people all too vividly that the divine right of kings had severe limits.

After the revolution Rokneddin went back, and tried to ply his trade again: this time he disappeared into prison never to be seen again. At the time the Shah’s proscription was seen as the act of an exotic tyrant. Not a bit of it. We can do just as well at home. During the period of George III’s madness in 18th century Britain, King Lear was banished from the stage because the parallels were too obvious.

Shakespeare has had this unique symbolic significance for a long time. From the end of the 17th century, initially in England, and then increasingly in translation across Europe, his stock began its inexorable rise, until he was acclaimed across the whole of the Western world, to a degree never before or since equalled by any other writer. His work was a mirror in which people of widely diverse cultures could see themselves – in Scandinavia, in the Near East, in Spain and the Americas.

He was fervently admired in France, despite his barbaric non-conformism to the laws of classical drama. In Germany and Russia, he was clasped to those nations’ bosoms, claimed by them as, respectively, German and Russian. Shakespeare’s perceived universality – which expanded in the 19th and 20th centuries to include Africa, India, China and Japan – inevitably meant that his work would be recruited to embody the positions of various political and philosophical groupings. And with this came, equally inevitably, censorship and suppression.

Not that Shakespeare was a stranger to censorship in his own time, living and working as he did in, first, the Elizabethan, then the Jacobean, police state where people’s actions and their very thoughts were under constant surveillance. The theatre in which he worked was heavily patrolled by the Master of the Revels, who was charged not only with providing entertainment for the monarch, but with averting controversy, particularly in the sphere of foreign relations. Sometimes this meant deleting matters offensive to allies, sometimes it meant suppressing criticism – or perceived criticism – of the crown, sometimes, more rarely, it meant eliminating morally or sexually offensive material. The theatre was a minefield of significance for dramatists and their companies. Even a simple dig at German and Spanish dress had to be cut from Much Ado About Nothing because of contemporary diplomatic sensitivities. But the reach of the censor went well beyond the explicit …

This is an abridged version of Simon Callow’s in-depth feature for Index on Censorship magazine’s special Shakespeare issue. To read the full piece, which also looks at the role of the Master of the Revels (who Callow portrayed in the Oscar-winning film Shakespeare in Love), buy a print copy or download a digital version via Exact Editions. Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.