Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Yeni Bir Şarkı Söylemek Lazım, Video, 2016, Işıl Eğrikavuk

Asena Günal is the program coordinator of Depo which is a center for arts and culture at Tophane, Istanbul. She is one of the co-founders of Siyah Bant, a research platform that documents censorship in the arts in Turkey.

“Is it just me? I don’t think so, but these days I’m in a state where I don’t know what to hold on to, what to do. I push myself to continue my work. Should I continue with art, or should I channel myself to more urgent things; that’s how suffocated I feel,” Hale Tenger, a prominent contemporary artist from Turkey, said in a roundtable discussion published in the Istanbul Art News.1 This pessimism reflects the general mood of artists and many other intellectuals in Turkey, a country that has experienced incidents so numerous in the past year that they could fill decades.

Since July 2015, almost 300 people have been killed and thousands wounded in various attacks by IS and the Kurdistan Freedom Eagles (TAK). After the elections in June 2015, in which the Kurdish party passed the 10% threshold and AKP lost its single party position, president Erdoğan pushed for another election. In November 2015, the AKP won the election and ended the peace process with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The government put severe limitations on the Kurdish and pro-peace opposition. A total of 2,212 academics, who signed a petition to condemn the state violence in the southeast of Turkey, have been targeted by Erdoğan, received threats, have been faced with criminal and disciplinary investigations, and four of them were detained and jailed for about a month. A growing number of academics have been dismissed or suspended, some were forced to resign and had to leave the country. Almost two thousand lawsuits have been filed against people alleged to have insulted the president online or offline.2

In January 2016, two members of the art community were arrested and then sued for participating in the peaceful demonstration “I am Walking for Peace” in Diyarbakır. The march was organised to protest state violence in the Kurdish region and ask for the restarting of the peace process. Artists Pınar Öğrenci and Atalay Yeni were arrested and then released conditionally. Their court cases still continue.

The impact of the recommencement of the war has made itself felt in various fields and ways. The cancellation of the exhibition “Post-Peace” in February 2016 shows the difficulty of expressing critical views on state policies. The exhibition curated by an Amsterdam-based curator Katia Krupennikova was cancelled by the institution Aksanat just five days before the opening, with the director citing the rising tension and the mourning after another bombing in Turkey as the reason. Given that other events went on as scheduled, many thought one of the video works in the exhibition, critical of the dirty war policies of the Turkish state against the Kurdish guerilla was considered risky by Aksanat.3 This was one of the incidents in which the state itself did not act, and actors in the artistic community took on this role. It created a discussion in the art scene about how to struggle in times of repression.4

Ayhan ve ben (Ayhan and me) from belit on Vimeo.

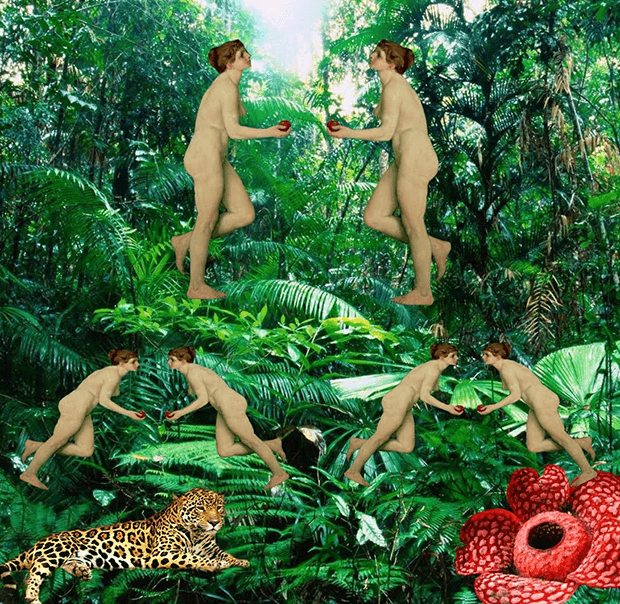

In April 2016, the screen of the public art project YAMA on a hotel roof was shut down by the Istanbul municipality on the basis of an anonymous complaint, claiming that the work of artist Işıl Eğrikavuk, a video animation, projecting the slogan “Finish up your apple, Eve!”, insulted religious sensibilities. When pressed, the municipality cited “visual pollution” as the reason for discontinuing the screening. This turn illustrates a strategy by the national and local government to legitimise their acts of censorship as purely procedural and administrative actions. After Eğrikavuk made a statement, YAMA’s curator Övül Durmuşoğlu declared the project’s support for the artist. Durmuşoğlu organised a meeting to discuss the case and invited Egrikavuk, legal consultants and people from the art scene. In the following days, Eğrikavuk did a performance based on this restraint. Both the meeting and the performance attracted a wide audience.

Even before the coup attempt of 15 July, there was such an atmosphere where people were worried about terrorist attacks, human rights violations, and limitations on freedom of expression. The coup attempt left 246 citizens and 24 coup planners dead and a nation deeply traumatised. The Gülen movement is accused of being behind the last coup attempt. The coup attempt was followed by a State of Emergency which allowed the cabinet under the chairmanship of the president to issue decrees that have the force of law.5 Unsurprisingly, Erdoğan has been using the attempt as an opportunity to eliminate critical voices.

In the five days between the coup attempt and the declaration of State of Emergency on 20 July, many festivals, biennials and concerts were postponed or cancelled by their organisers. The Sinop Biennial (Sinopale) was postponed “due to recent events in Turkey”, the One Love Festival was cancelled “due to availability problems on the schedules of artists and groups”, many concerts of the Istanbul Jazz festival including a performance by Joan Baez was cancelled6, Muse cancelled its concert“due to recent capricious events” and Skunk Anansie did the same “in light of the recent extraordinary events”. One issue of the satirical magazine Leman was banned as it suggested that both soldiers and civilians involved in the country’s recent unsuccessful coup were pawns in a larger game.

After the coup attempt, Erdoğan called the people to “Democracy Watch”-meetings. The biggest and final meeting, was the one at Yenikapı on 7 August 2016.7 Erdoğan invited popular figures, like singers, actors, and actresses to join the meeting. Pop singer Sıla announced on social media that although she was against the coup she would not be part of such a “show” and would not participate in the big meeting in Yenikapı. Sıla was the only figure brave enough to make such a declaration and not step back. But this resulted in the cancellation of her concerts in five different cities. Many people supported her by sharing her music videos and their own photos with an album of Sıla online.

Theatre actor Genco Erkal’s company “Dostlar Tiyatrosu” was banned from performing a play based on the writings of Turkish communist poet Nazim Hikmet and Bertolt Brecht. It was going to be performed in the garden of Kadıköy High School but the school cancelled the contract due to security reasons. It was obvious that security was not the issue and the school was under pressure from the Ministry of Education because of Genco Erkal’s critical stance. After protests of the theater company and members of the main opposition party (CHP), who brought the case to the Parliament, the Governorate lifted the ban.

Municipal and state theaters have been under a tight grip for some time and there have been ongoing discussions about privatisation of these institutions. The State of Emergency not only aimed at Gülenists who were accused of being part of the planning of the coup but also many artists with apparent oppositional stance were affected. On 1 August, the Istanbul Municipality fired 20 people, including director Ragıp Yavuz, actor Kemal Kocatürk, and actress Sevinç Erbulak from the Municipal Theatre based on the decree law number 667 which was announced after the declaration of the State of Emergency. They were not even granted an explanation for why they lost their jobs, but only received a vague reference to supposedly having failed “the evaluation criteria”8. Obviously, they did not have any connection with coup plotters. Eleven of them have been reinstated in their former positions.

Besides bans and purges, the State of Emergency has enabled the government to re-regulate the organisational structure of the state. A new law that would bring the privatisation of State Theatre, State Opera and Ballet, Atatürk Cultural Center, and Turkish Historical Society was discussed in Parliament. Many people from the field of theatre, opera and ballet expressed their concern that the State of Emergency might be utilised to bring privatisation after years of discussion on instating an independent arts council.

It is now common for the members of the ruling party to randomly target artists, writers, or academics in order to intimidate wider cultural milieu. A recent example is from the field of contemporary arts: In September 2016, an AKP MP Bülent Turan targeted the curator of the Çanakkale Biennial Beral Madra and called on the Çanakkale Municipality (run by CHP) not to work with her. The accusation was being critical of Erdoğan, and hence -so the argument went further- being “pro-coup”. Madra became a target because of her critical tweets and Facebook posts. Being critical of Erdoğan has long been risky but now it is associated with being “pro-coup”. Beral Madra withdrew from her position as to not put the Biennial at risk. Then the organising institution announced that the biennial would be cancelled altogether. They were saddened by the current political atmosphere, which did not place art as a primary point of concern. The CHP-run municipality and many people from the art scene expressed concern over the cancellation, highlighting instead the potential of art to counter the authoritarian discourse of AKP and expressing their wishes for the Biennial to go ahead as planned.

Despite this rising authoritarianism and the pessimistic atmosphere, Turkey’s culture and art scene will continue its struggle. Last week there were many openings in different galleries around Istanbul and almost all of them were crowded. People from the art scene are in need of each other more than ever, aware of the vital importance of solidarity in times of hardship. Film, music, dance and performance festivals started to take place, their posters filling the streets. So I would like to finish with another quote from the same issue of Istanbul Art News, by Deniz Artun,9 the director of Ankara Galeri Nev, as I tend to share its optimistic sentiment: “I guess that art history has shown us time and again just how deep the traces left by exhibitions, artworks, artists emerging with ‘pertinacity’ will be; not those amidst freedoms and prosperity, but those coming forth among fears and uncertainties that are burdensome for all of us.”

More about the arts in Turkey:

Belit Sağ: Refusing to accept Turkey’s silencing of artistic expression

Life is getting harder for objective journalists in Turkey, says cartoonist sued by Erdogan

Turkey: Artistic freedom and censorship

Turkey: Artists engaged in Kurdish rights struggle face limits on free expression

Veli Başyiğit for Siyah Bant

Siyah Bant (Black Bar) is a platform established in 2011 to research and document cases of censorship in the arts in Turkey and to defend artistic freedom of expression.

The Siyah Bant initiative, which carries out research on censorship of the arts in Turkey, has given much coverage to obstacles to freedom of expression in the cinematic field in research published in recent years. Cases of censorship at film festivals in Turkey have become increasingly common, more visible and have brought about devastating changes, creating a need for research focusing particularly on restrictions of freedom of expression at festivals. In this report, we aim to lay out the strategies followed by film festivals in response to pressures to censor cinematic works and to develop the groundwork for increasing the possibility of resistance to censorship.

Recent censorship cases

Film festivals in Turkey have been the stage for two widely-publicised cases of censorship in 2014 and 2015.

Firstly, Reyan Tuvi’s documentary about the Gezi Park demonstrations entitled Yeryüzü Aşkın Yüzü Oluncaya Dek (Until the Face of the Earth Becomes a Face of Love) (2014) was removed from the programme of the 51st International Antalya Film Festival in 2014 by festival organisers after a warning that showing the film may commit the crime of insulting Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan under the 125th (insulting) and 299th clauses (insulting the president) of Turkish Criminal Law. However, the film had been found by the festival’s National Documentary Film Competition preliminary jury as being worthy of inclusion in the competition. The preliminary jury — Ayşe Çetinbaş, Berke Baş and Seray Genç — revealed the situation to the public in a statement in which they announced their resignations, saying they “would not be any part of such censorship”. In reaction to the film’s censorship, first National Documentary Film Competition Main Jury President Can Candan, and later ten other jury members due to judge various competitions, also announced their withdrawal from the festival. Directors of 13 of the 15 films in the National Documentary Film Competition category also withdrew their films in protest. As a result, the festival organisers announced the cancellation of competition in that category. This case of censorship in Antalya, as Siyah Bant’s Banu Karaca has highlighted, can be seen as “an example of a situation in which the state itself did not act, and actors in the artistic community took on this role”. In Siyah Bant’s statement on the Antalya censorship case, it emphasised that the legal clauses that make insult a crime and which were given as the reason for the removal of Yeryüzü Aşkın Yüzü Oluncaya Dek from the festival programme constituted a serious obstacle to freedom of expression, and for this reason should be completely revoked.

The second case of censorship was the last-minute cancellation of the showing of the documentary Bakur (North) (2015) at the 34th Istanbul Film Festival on 12 April 2015. The film, directed by Çayan Demirel and Ertuğrul Mavioğlu, took the everyday lives of PKK guerrillas as its subject. The festival organisers stated that the showing of Bakur had been cancelled after a notice received from the Culture and Tourism Ministry “reminding them that all films created in Turkey to be shown at the festival must have obtained a registration document”. But it was clear that the prevention of the film showing was not merely about the lack of a registration document.

Mavioğlu, one of the film’s directors, had been targeted in Vahdet newspaper with a subheading “Here is the director of that traitorous PKK film” on 10 April 2015. Even though the reminder sent by the Ministry did not specifically state that Bakur was not to be shown, it did highlight that the film had been banned once before. Moreover, it emerged that the General Manager of Cinema of the time, Cem Erkul, had called the Istanbul Culture and Art Foundation (IKSV) in relation to the showing of Bakur. Police officers came to check whether the film was being shown on 11 and 12 April and warned festival staff not to put it on as it would be difficult to assure the safety of viewers if they did. The reaction to the case of censorship in Antalya the previous year had been mostly limited to documentary filmmakers. In contrast, following the censorship of Bakur, all the films in the national feature-length film categories were temporarily withdrawn. Filmmakers came together after the film’s banning to announce they had withdrawn 22 films from the festival. Next, the jury members at the festival let it be known that they were withdrawing. The festival organisers announced that they had cancelled the National and International Golden Tulip Competitions and the National Documentary Competition. In addition, filmmakers and cinematic organisations made a joint statement calling for “the laws and regulations that make censorship possible to be urgently changed”. Bakur, which could not be shown at the Istanbul Film Festival, was shown simultaneously on 3 May, World Press Freedom Day, in Istanbul and Diyarbakır, on 5 May as part of the Itinerant Film Days in Mardin, on 12 May for the Kurdish Culture and Art Days in Istanbul, on 15 June as part of the Censored Documentaries selection as part of the Documentarist 8th Istanbul Film Days, and also on various occasions in Izmir, Van, Mersin, Siirt and Batman.

The prevention of the screening of Bakur at the Istanbul Film Festival can be said to have marked the beginning of a new era for film festivals in Turkey. While before the censorship of Bakur, very few festivals asked for films’ registration documents, we have now come to the point where a significant number require these documents before they will add films to their programmes. In addition to the Istanbul Film Festival, at which last year’s case occurred, the Ankara International Film Festival, the !f Istanbul Independent Film Festival and the Ankara Accessible Film Festival are now among those that have begun to require films’ registration documents before putting them on their programmes.

The Ankara International Film Festival, which did not require registration documents for films before 2015, in 2016 requested this document from all the producers of films that passed the pre-screening to be added to the programme. Two directors who said that registration documents were being used as a form of censorship and, for this reason, they would not get them, had their films removed from the programme announced for the 27th Ankara International Film Festival.

These two films were Selim Yıldız’s documentary Bîra Mi’têtin (I Remember) (2016) about the Roboski massacre and smuggling activities, and Gökalp Gönen’s Altın Vuruş (Golden Shot) (2015), a short animation about machines living in small houses and searching for the sun. Necati Sönmez, one of Documentarist’s directors, announced his withdrawal from the documentary competition jury on Hatırlıyorum being taken off the programme for “acquiescing to censorship”. After the issue came to public attention, the festival organisers made a statement calling the condition that films to be shown have registration documents a “technical and legal necessity”. Sönmez responded to this announcement, saying “When a document licensing a work becomes a requirement for it to enter a festival, it doesn’t stop being a censorship document; on the contrary, it (censorship) is institutionalised.”

The Legal Dimension of Registration Documentation

The basic function of a registration document is to allow the owners of a cinematic or musical work “to not have their rights violated, to easily prove their ownership rights and to keep track of their authority to benefit in relation to their financial rights”. The ambiguities in regulations concerning for which screenings these registration documents are required have laid the groundwork for them to be used for purposes other than their function, which is to prove that those screening a film for commercial purposes have the right to do so. Another problem is the requirement for those applying for registration to first have a “document showing the outcomes of the evaluation and classification processes”. Ulaş Karan emphasises that this evaluation and classification “sometimes forms a pre-inspection and opens the way for a cinema film to be censored”.

Another problem regarding the registration documents is that some films17 shown at film festivals are not given them due to decisions that they “cannot enter commercial circulation and screening”. The subjection of films by these rules to a pre-inspection according to unclear criteria such as conforming to the Constitution and the protection of general morality and public order makes it possible for some films to be banned regardless of whether they are for commercial purposes or not. In order to solve this problem, we recommend that the registration procedure is separated from the evaluation and classification procedures. Every completed film must be given a registration document without condition, and in addition, the age limits for commercial films should be assigned according to universal criteria. If a film showing is believed to represent a crime, this can be subjected to a trial afterwards. At this point, we can add that the debate on registration documents is wider than simply providing an exemption for showings at festivals. The real issue is that registration documents should only prove rights ownership, and should not have the features that presently allow it to be used for the pre-inspection and banning of films.

In short, the registration documents are not a problem for as long as they are used in the way directed by the Ideas and Artistic Works Law, that is, for the functions of proving rights ownership for commercial distribution and ensuring that people enjoy their property rights. As Ulaş Karan has explained, this document has an essential function for the commercial distribution and showing of films.18 However, when no distinctions are made between commercial and non-commercial showings and the evaluation and classification of films is made a prerequisite for registration, the way is opened up for registration documents to be used as a vehicle for censorship. Hence, steps need to be taken to remove the requirement for a registration document at non-commercial showings at which there is no need to prove property rights. In addition, we must emphasise that the evaluation and classification carried out for commercial screenings should be kept separate from the registration process and be reorganised in line with international standards in a way that does not infringe on freedom of expression.

The Registration Document as a Tool of Censorship

Up until the 2015 Istanbul Film Festival intervention, most films shown at film festivals were in practice exempted from the requirement of a registration document by the ministry “turning a blind eye”. However, we do know of other films prevented from being shown at festivals due to not having registration documents or having had their applications for the documents rejected. The main cases over this time period can be listed as follows: in 2007, police requested to pre-vet the film Dersim 38, planned to be screened at the 1st Munzur Peace and Culture Days as it had no registration document. When the organisers rejected this request, the screening did not take place. Moreover, the film was banned in 2007, and the legal appeals still continue to the present day. The application for a registration document for Aydın Orak’s documentary Bêrîvan: Bir Başkaldırı Destanı (Berivan: The Saga of an Uprising) about the 1992 Newroz festival in Cizre was rejected in 2011 with the allegations that it “made PKK propaganda” and “twisted history”. The film was blocked from being shown at the 2nd Yılmaz Güney Film Festival in December 2011 by the Governor of Batman. Caner Alper and Mehmet Binay, who directed the film Zenne (2011), which focuses on hate crimes against LGBTI individuals, have stated that there were attempts in 2011 to prevent their film being shown at a national competition it had qualified for in prescreening two weeks before the festival began on the basis of it not having a registration document. In the end, Zenne’s producers could not get all the documents it required to get a registration document in that short of a timeframe, and along with Unutma Beni İstanbul (Don’t Forget Me, Istanbul) (2011), which also had no registration document, it was not shown at Malatya. The films Hayatboyu (Lifelong) (2013), Köksüz (Rootless) (2013) and Daire (Circle) (2013) were taken off the programme at the 4th Malatya International Film Festival in 2013 for the same reason.

In January 2014, the Culture and Tourism Ministry General Directorate of Cinema sent a circular to many different festivals reminding them of the condition that they require registration documents from domestic films. In fact, from 2011 onwards, the ministry had sent this circular to film festivals it had financially supported, but as mentioned above, this condition had not been imposed by the majority of festivals. Moreover, neither did the ministry follow-up on this. An open letter to the Culture and Tourism Ministry on 7 March 2014, prepared by Siyah Bant together with filmmakers, film institutions and film festivals, explained how requiring registration documents for artistic events other than commercial screenings represented an obstacle to artistic freedom of expression and requested that regulations be changed to remove this requirement. Mustafa Ünlü, the director of the 1001 Documentary Film Festival, said that they had received similar circulars in the past, but after meeting with the ministry this regulation was not put into practice. Ünlü related that after the 2014 circular, they had met with the ministry to request that the responsibility to require registration documents be lifted, while ministry representatives had highlighted a new cinema law as the solution to the problem. This draft law would be regularly used as an excuse by ministry officials in their responses to the requests of filmmakers and festivals. This planned law, named the Turkey Cinema Law, came onto the agenda in 2012. As explained by lawyer Burhan Gün, this draft law removed the criminal penalties for non-commercial screenings. But despite all the efforts of cinematic professional associations in this period, they were unable to establish healthy communications with the Cinema General Directorate. From the beginning of the period, the associations made proposals in relation to the development of the sector to those working on the draft law, but none were included in the law drafting process. It is unknown what the latest situation is with the draft law, which has now been off the agenda for a while.

As can be seen from the examples of Bakur, Bêrîvan, Dersim 38 and Zenne, registration documents appear to be a useful means of preventing the screening of films, mostly those relating to the struggle for Kurdish rights, that the state does not want to be screened. In other words, it forms an inspection mechanism allowing committees connected to the Culture and Tourism Ministry to intervene on the basis of the content of films. The festivals where films have been removed due to not having registration documents have generally not mentioned the content of these films in their statements on the matter. A good example of this is the situation at this year’s Ankara International Film Festival. The festival organisers gave the reason for Hatırlıyorum being taken off the program not as related to the film’s content, but due to “technical and legal necessities”. Therefore, the festival organisers, in referring to “technical and legal necessities”, left any film that had its registration document application rejected out of their program for reasons unrelated to its content; Hatırlıyorum and Altın Vuruş being removed are examples of these.

Short Films and Documentaries

As was seen at the 27th Ankara International Film Festival, the registration document requirement has disproportionately affected short films and documentaries. These films, which rarely have commercial showings, are generally seen by viewers during the course of film festivals. Before the censorship at Istanbul Film Festival, almost no festival required registration documents from short films and documentaries. However, with the changes that occured at many festivals following Bakur, short films and documentaries were also required to provide registration documents. These films now need to get registration documents — and, consequently, go through evaluation and classification procedures — in order to be shown at certain festivals. For documentaries, which generally do not see commercial release and tend to have much lower budgets in comparison with fictional films, to comply with these administrative regulations, which involve establishing a production company and paying the fees for these procedures, will be very difficult.

The Main Problems Film Festivals Experience

It needs to be made clear that the censorship at the Istanbul Film Festival has serious consequences for film festivals in Turkey that go beyond debates surrounding registration documents. The Istanbul Film Festival’s inability to stand against the ministry’s intervention with the intention of censoring one particular film and the cancellation of film showings at later festivals where the films did not have registration documents have weakened the hand of film festivals in Turkey and made it easier for various further interventions to take place more openly.

Film festivals have also had their share of the stifling atmosphere created in the wake of war restarting between the PKK and state forces in July 2015 and consequent massacres. The 18th 1001 Documentary Film Festival, which was to take place in October 2015, was postponed until further notice. The decision to postpone it, as announced on 19 September 2015, was taken in “an environment of bloody clashes, loss of life, curfews, mob and organised violence” and “uncertainties that have multiplied in the tensions created by the electoral atmosphere”.

Following the censorship of Reyan Tuvi’s documentary in 2014, a question mark hung over whether or not the International Antalya Altın Portakal Film Festival would go ahead in 2015 or not. Later, it was announced that due to the 1 November 2015 elections and the G-20 summit in Antalya, the festival would be postponed to December 2015 and renamed the “International Antalya Film Festival”. Even more importantly, the National Short Film Contest, which had been held in previous years, and the National Documentary Film Contest, which was hit by the censorship crisis in 2014, were permanently removed from the festival.

As the programme director of the Adana Altın Koza Film Festival, Kadir Beycioğlu, has expressed, the opening and closing ceremonies, as well as all events other than the screenings and the participation of guest filmmakers, were cancelled due to the losses of life at Dağlıca and Iğdır. Beycioğlu stated that the Adana Metropolitan Municipal Assembly had debated cancelling the entire festival and allocating its budget to the families of fallen security forces. He added that, after talks with municipal officials and sector representatives, they had decided to only go ahead with the competitions, and to allow both Adana cinema-lovers and the people’s jury to watch the competition films. Beycioğlu said that from 1992, when he had taken on the management of the festival, to the present day, the municipality had never interfered with the programme, but said that for almost every municipality-organised film festival, many matters outside the programme were decided in conjunction with the mayor or went ahead with his or her approval, and that some decisions might be made by the mayor alone. Beycioğlu said that these situations often revealed how mayors and their teams felt about festivals and what they expected from them.

Bureaucratic Difficulties

The approval document provided by the Artistic Events Commission (SEK), which is responsible for giving approval for films created overseas to be shown at festivals and similar events held in Turkey, also makes customs procedures for films sent from overseas easier. International logistics firms such as DHL and FedEx request the approval document from SEK for customs procedures for the Digital Cinema Package (DCP) copies of films brought from overseas for festivals. Bilge Taş, Gizem Bayıksel and Esra Özban of the Pink Life QueerFest team explain that their application for an approval document for the films at their festival in 2015 did not receive a response in time, so some of the DCP copies did not go through customs and some showings had to be carried out from BluRay copies. For the fifth festival, held this year, this was not the only problem relating to customs procedures. They say that at the start of this year the Atatürk Airport Customs Directorate asked them to provide anew their customs documents for the 35 mm copies of the five films that they had had to show on BluRay at the first QueerFest held in 2012. The festival administration explained that there had been no missing documents for the customs procedures in 2012, but the directorate did not respond in any way. We can say that these prohibitive practices that QueerFest have met with in terms of customs procedures are carried out as a form of censorship.

But customs procedures are not the only problems that QueerFest, who have not had any form of communication with the Culture and Tourism Ministry for five years. The festival team, who describe their goal as “creating areas of expression for the LGBTI rights struggle through art” believe that the ministry is following a policy of ignoring them and that this policy represents a “form of censorship that cannot be fought”. They say that there has been no response to their applications for ministry support in 2012 when the festival was set up. Moreover, they complain that for five years, they have not been able to access any film they have requested from the ministry archives. The festival, which shows an extremely limited number of local films, does not request registration documents for those they show.

Repression Directed at Festival Venues

In our discussions with festivals, we came to understand that the increasing repression was directed as much against festival venues as against festivals themselves. The QueerFest team state that the Beyoğlu Pera Cinema and Moda Stage had asked for registration documents for films they were showing in Istanbul in 2015, showing that the ministry had directly required the documents from them. Therefore, at QueerFest 2015, no domestic films were shown, and as mentioned above, there is an exemption for these documents for foreign films at festival showings. We must also add that the Istanbul Modern rejected QueerFest’s request to be a venue for 2016, albeit saying they had decided only to host the events of another group, İKSV.

The chancellorship of Ege University refused permission for the 8th Aegean Documentary Film Days, which were to be held in Izmir between 14-17 May 2015, to be held on the university’s main campus, giving the declaration of a state of emergency at the university as a reason. The festival, which had taken place for the past seven years at Ege University, was held at the Izmir French Cultural Center in 2015. Necati Sönmez, one of Documentarist’s directors, remarked that this year they had found it difficult to find a venue for the Documentarist 9th Istanbul Documentary Days, to be hosted between 28 May and 2 June, and, for this reason, they had mostly applied to venues in foreign consulates.

Another example of how the spaces where festival screenings are held are under pressure was seen at the March 2015 13th International Travelling Filmmor Women’s Films Festival. Municipal police raided the Rampa Theatre in Beyoğlu during a screening of Piçler (Bastards) (2014) with the participation of director Nassima Guessoum, on the basis that there was no licence for the film showing. Municipal police officers’ attempt to prevent the screening met resistance from the festival team and the audience. The festival coordinators met with the Beyoğlu Municipality and members of parliament and stopped the municipal police action. Most recently, a screening of Sara: Hep Kavgaydı Yaşamım (Sara: My Life Was Always A Struggle) (2015), a documentary about the life of Sakine Cansız, one of the founders of the PKK who was murdered in Paris in 2013, at the Beyoğlu Atlas Cinema on 19 January 2016 was cancelled by police. Artists from the Mesopotamian Cultural Center (MKM), which organised the event, were called to the Beyoğlu Police Station before the screening and told “we cannot guarantee your lives, you cannot show the film”. On 21 January 2016 a second screening at the Aksaray Su Performance Center was prevented for the same reason. International Worker’s Film Festival co-ordinator Önder Özdemir says that since the censorship of Bakur, the repression of festivals had increased and that the raiding of festival venues during film screenings was no longer an unlikely prospect.

One of the situations faced by festivals we talked to was people arriving in plain clothes to “visit” film showings and asking organisers specific questions about the content and technical specifications of the films. Documentarist director Necati Sönmez and coordinator Öykü Aytulum told us about plain-clothes individuals directing questions about the film’s content to them during showings of Kadınlar Cizre ve Silopi’yi Anlatıyor (Women Explain Cizre and Silopi) (2015) and Dengbej (Minstrel) (2014) at SALT Beyoğlu at the 7th What Human Rights? Film Festival in December 2015. Similarly, Flying Broom International Women’s Film Festival co-ordinator Onur Çimen said that plain-clothed individuals they assumed were police or ministry employees asked whether they had registration documents for the films they were showing during the screenings of films at the 18th Flying Broom festival in 2015.

In Place of a Conclusion

The developments and cases of censorship we have touched upon in this report are symptomatic of an increasing narrowing of the spaces for expression provided by film festivals over recent years. Today, the primary goal of the fight against censorship at film festivals in Turkey must be the removal of the inspection and censorship mechanism carried out by the state using registration documents. However, as we have mentioned above, uncertainties relating to the implementation of the registration document make this struggle extremely difficult. These arbitrary measures may be taken to court by filmmakers and directors. In addition, during the court cases, institutions and individuals may come together to organise in powerful solidarity. The common demands they develop may be shared with the public through these “strategic legal cases”.

The use of registration documents as a mode of censorship is not only limited to film festivals. The existing regulations on documentaries function as a pre-vetting mechanism for screenings, meaning that it is almost impossible for Bakur and similar films to get registration documents. Thus, it would be best for actors in the field of cinema not to limit the debate to a specific exemption for registration documents for documentaries at festivals, but to begin an integrated struggle against all regulations that censor films.

Another point that should not be forgotten is that the registration documents we have recently seen intensively used as a method of censorship is only one such method. As discussed in this report, freedom of expression is also limited at film festivals by methods such as difficulties created at customs, repressive measures directed at festival venues, and direct targeting and threats. Besides these, there are many indirect ways in which festivals are put under new types of inspection, such as the agreements prepared for those receiving support from the Culture and Tourism Ministry and statements made by the Artistic Events Commission. The alternative methods that these film festivals have developed to resist these censorious measures form an important example. However, these alternative methods are sometimes temporary solutions aimed merely at “saving the day”. This situation may form an obstacle to a joint struggle between festivals and film manufacturers. As we find ourselves in a period in which “the grip is tightening” in a way that will affect every actor in the cinematic field in the long term, a solidarity platform must be formed of a wide array of actors in response to repressive measures that affect freedom of expression. However, we generally see a sudden increase in solidarity in the cinema world after censorship cases, but this solidarity not being continued over the following period. The truth is that film festivals and other actors in the cinematic field need to bring their demands that the necessary regulations be made and its implementation become a standard and transparent to the fore at every opportunity. Moreover, just as in other areas of freedom of expression governed by the Culture and Tourism Ministry, film festivals should be protected on a constitutional basis and the ministry should be responsible for giving its support.

E. Belit Sağ is a Turkish activist and artist

It was my intention for a long time to publish a statement about the censorship of my video Ayhan and me (2016), part of the group exhibition Post-Peace that was censored by Akbank Sanat. When the exhibition was censored, I wanted to prioritise the group statement of the collaborators and artists of the exhibition. The group statement is out, and it’s now my turn. I would like this statement to be seen as a contribution to the statements made by Katia Krupennikova, the curator of the show; the jury of the Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015; Anonymous Stateless Immigrants Movement; and the artist and contributors of the exhibition Post-Peace. With this statement, I aim to share my own experience.

I am the only artist from Turkey that was supposed to take part in the group exhibition Post-Peace. My initial proposal was specifically about Turkey. This proposal went through a censorship process starting months before the originally planned opening date. I’d like to share my experience with the hope that it will shed a little bit of light on the censorship that of the exhibition itself and the problem of censorship in the art field more generally.

The group exhibition Post-Peace was initially planned to take place in Amsterdam. I was invited by the curator at this early stage. Later on, with this exhibition concept, Katia Krupennikova applied for and won the Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015. The exhibition moved from Amsterdam to Istanbul. In one of the talks Katia had with Akbank Sanat managers in November 2015, she mentioned to them my proposal. They told Katia that the political situation in Turkey is tense and that they can not commission the proposed work. Katia asked for an official statement from the director of Akbank Sanat, Derya Bigalı. She didn’t receive a reply. I met Katia when she came back to Amsterdam. We wrote together to Zeynep Arınç from Akbank Sanat, with whom Katia has been in contact throughout the process. We asked for a formal rejection letter from the director, explaining the reasons for their decision. Zeynep Arınç replied to our email informally telling Katia that Akbank Sanat can not commission this work.

My initial work proposal, censored by Akbank Sanat, was about Ayhan Çarkın. Ayhan Çarkın was part of JITEM, an unofficial paramilitary wing of the Turkish Security Forces active in mass executions of the Kurdish population in the 1990s. As a part of the deep state and JITEM, Ayhan Çarkın confessed in 2011 that he led operations that killed over 1000 Kurdish people during the 1990s. These confessions were made on television, and videos from those confessions are accessible on Youtube. The work I was planning to make was about Ayhan Çarkın’s personal transformation, how historical reality is constructed, and how to think about the term ‘evil’. This work, which was only a written proposal at that point, was censored by Akbank Sanat, even though it was part of the curator’s exhibition concept from the very beginning, and was chosen by an international jury as part of the exhibition for Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015.

This was the first time something like this had happened to me. Instead of leaving the exhibition, Katia and I came up with a proposal for a new work. The new work was going to talk about the censorship of my previous proposal, as well as the politics of images of war in Turkey. Akbank Sanat requested to see the script of this new work. Katia didn’t respond to this request, and I told her that I’m not in favour of showing the script, due to Akbank Sanat’s attitude up till that point. Consequently, we asked the founder of the Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition, curator Başak Şenova, for her opinion on this issue. At first she supported us, but after she consulted with Akbank Sanat she told us that the refusal by Akbank Sanat is understandable. To be honest these reactions made me feel alone. Turkey is really going through a tough period, and I started questioning why, as an artist, I was putting the whole institution at risk.

In December before I started producing my second proposal I realised that I did not feel comfortable with accepting the situation as it was. I decided to make the censorship public, by writing a letter and sending it to the press. I met with Katia and we started writing an email explaining the situation to the jury. In mid-January, before we finalised the letter, Katia told me that she talked to Akbank Sanat and they agreed to the new proposal and no longer demanded to see the script in advance. I started making the video. I got in contact with Siyah Bant, a group that deals with censorship in the field of art in Turkey. I got a lot of support from them, which helped against the feeling of isolation such censorship cases cause. Also, we started thinking about ways to deal with this specific case. The final video took shape as a result of this process. I believe watching the video complements this statement.

Ayhan ve ben (Ayhan and me) from belit on Vimeo.

The video was finalised on 23 February, and Katia Krupennikova presented all the works to Akbank Sanat for a technical check on the same day. The exhibition was supposed to open on 1 March, and it was cancelled/censored on 25 February. There was no exhibition announcement on Akbank Sanat’s website or social media accounts, or there was any exhibition poster at Akbank Sanat’s space at any point. This makes me think that Akbank Sanat has been considering this decision for a long time, but didn’t communicate it to the curator or any other contributor of the show.

I don’t know and will never get definite confirmation whether the cancellation of Post-Peace was related to the content of my work or not. However, this does not change what happened. Together with Siyah Bant, we prepared a press release explaining the censorship prior to the cancellation of the exhibition. Even if the exhibition had not been cancelled, I was planning to publicise my experience of Akbank Sanat’s censorship.

In the 90s, Akbank Sanat hosted a painting exhibition by Kenan Evren. Kenan Evren is the leader of the 1980 coup d’etat in Turkey. Akbank Sanat has had several censorship cases in its history. Akbank Sanat gave Kenan Evren the possibility to exhibit his work as an “artist”, without questioning his leading role in the 1980 coup, from which the country still suffers. Akbank Sanat has never taken responsibility for this exhibition nor the role they took in it and what it means for Turkey. I do not believe that Akbank Sanat has or aims to acquire the ethical and conceptual capacity to host any exhibitions. The Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition that they have sponsored for the past four years is an important award in the international art world, which gives them a prestige they do not deserve.

At this point I have a number of questions to ask:

– Why does Akbank Sanat have the right to bypass the jury of Akbank Sanat International Curator Competition 2015 and the originally accepted plan of the exhibition? As mentioned in Başak Şenova’s statement following the cancellation: “Afterwards, Akbank Sanat unquestioningly implements all aspects of the exhibition”

– How does Akbank Sanat position itself in relation to the jury of the competition, the founding curator, the curator, and the artists of the exhibition?

– Why didn’t Akbank Sanat discuss the possibility of cancelling the exhibition together with the curator, the artists and the jury prior to the cancellation? Why does Akbank Sanat take decisions from the top, thereby marginalising the contributors and blocking their participation in decision-making mechanisms concerning the very exhibition they have been commissioned to make?

Institutions like Akbank Sanat will not admit that they censored the content of any exhibition, and will not take responsibility for the situation. These institutions interfere with cultural content due to their connections to corporations and banks, allied with oppressive government policies. This paves the way for normalising censorship and abusing the political situation of the country as an excuse, as in the text explaining the cancellation by the director of Akbank Sanat (“Turkey is still reeling from their emotional aftershocks and remains in a period of mourning.”).

I believe we need to expose these government-allied mentalities and structures over and over again. Institutions like Akbank Sanat can continue their activities because every time they censor the cultural arena they get away with it; their acts are not revealed, they are not held accountable, and they continue to receive support. Letting this happen deserts the fields of culture and art, and distances them from the struggles going on in the country. At the same time, this acceptance and silence obstructs those people and institutions that bravely resist, and further restricts already shrinking zones of freedom. We, as cultural and art workers, can counter this by refusing to accept the silencing of artistic expression.

Any cultural and art worker who is ignorant of the ongoing oppression in Turkey, who does not call censorship by its name, who does not see or fails to recognise the ongoing massacres in Kurdish lands becomes part of this oppressive structure. I have channels to speak out, I do not want to intimidate people who don’t have access to such channels, or who have to stay silent in order to avoid risking their lives. It is exactly for this reason, that we have to speak out en masse. I also think that ‘speaking out’ can happen in a variety of ways, just as acts of resistance do.

Although I have a hard time believing it myself, almost everyone I met in Cizre (a Kurdish town inside Turkey bordering Syria) in 2015, has either been killed or else left Cizre in order to stay alive. I owe this statement to the people I met in Cizre. Many other Kurdish towns and cities have suffered from or are currently undergoing similar attacks by Turkish State security forces. Every struggle in this region is connected, even though some might want to separate them. The one sharp difference is that some people get censored and others get killed in this country. Exactly because of this, we, the ones who get censored, need to keep ourselves connected to other resistances and realise of our privilege.

With this letter I wish to show solidarity with those working in the fields of culture and art who have already experienced or might experience similar censorships. My statement aims to express that we do not have to bear those abuses alone, with the hope that more of us will be able to speak up, and the hope that we can act collectively.

Last year, the exhibition Here Together Now was held at Matadero Madrid, Spain. Curated by Manuela Villa, it was realised with the support of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, Turkish Airlines and ARCOmadrid. But in the exhibition booklet, the explanatory notes to artist İz Öztat’s work “A Selection from the Utopie Folder (Zişan, 1917-1919)” was censored upon the request of the Turkish Embassy in Madrid, and the expressions “Armenian genocide” and the date “1915” were taken out.The case shows how the Turkish state delimits artistic expression in the projects it supports, and how it silences the institutions it cooperates with.

After Turkey was chosen as the country of focus for the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid International Contemporary Art Fair, the designated curator Vasıf Kortun and assistant curator Lara Fresko started to work with the galleries that would join the fair. They helped in fostering connections between the Madrid arts institutions and artists in Turkey; as well as with the embassy officers in charge of the financial support of events such as Here Together Now, which would run as a parallel event to the main fair. The embassy indicated that it would support this exhibition with the generous sum of €250,000. However, it did not provide any written documentation guaranteeing this support, and outlining the mutual duties and responsibilities of the parties involved. Likewise, during the realisation of the project, there was no written communication between the embassy and Matadero Madrid, and all negotiations took place verbally, over the phone. It was in this manner that, from the very beginning, the state kept the exact conditions of its support ambiguous and created a tense situation for the organisers. Ultimately, this working practice gave the Embassy the possibility of denying the promised support, in the event that their request was not carried out.

This is not the first case of the Turkish state censoring an arts event it sponsors abroad. We frequently hear about such cases off the record, and at times through the media. One of the best-known cases of state intervention took place in Switzerland, during the 2007 Culturespaces Festival. Director Hüseyin Karabey’s film Gitmek – My Marlon and Brando, which had received support from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism, was taken out of the festival program at the very last minute, at the request of an officer from the General Directorate of Promotion Fund, on the pretext that “a Turkish girl cannot fall in love with a Kurdish boy” as was the case in the film. The officer threatened the festival organisers with withdrawal of sponsorship totaling €400,000 — much like the case of the Madrid exhibition. The festival director decided that they could not go ahead with the event without this support, ceded to the censorship request, and accepted to take the film out of the program. However, independent movie theaters in Switzerland criticised this decision and ended up screening the film independently of the festival.

Both examples show that the state controls the content of the projects it sponsors abroad, interferes with the organisations on arbitrary grounds, and violates artists’ rights by threatening the very institutions it collaborates with.

The administrative channel for the state’s support to events outside of Turkey is the Ministry of Culture and Tourism’s Promotion Fund Committee, established under law 3230 (10 June, 1985) with the aim of supporting activities that “promote Turkey’s history, language, culture and arts, touristic values and natural riches”. The Committee reports directly to the Prime Minister’s office, and is presided over either by the Prime Minister himself, the Vice Prime Minister or a minister designated by the PM. It has five more members: Deputy Undersecretaries from the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, as well as the general managers of the Directorate General of Press and Information, and the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT). The objective of the fund is “to provide financial support to agencies set up to promote various aspects of Turkey domestically and overseas, to disseminate Turkish cultural heritage, to influence the international public opinion in the direction of our national interests, to support efforts of public diplomacy, and to render the state archive service more effective”.

The Committee convenes at least four times a year upon the invitation of its president to evaluate project applications. The only criterion in accepting a project is whether it complies with the objectives mentioned above. After the Committee carries out its evaluation, the projects are put into practice upon the approval of the PM. Representative offices of the Promotion Fund Committee monitor whether the projects are implemented in compliance with the principles of the fund. In the case of the Madrid exhibition, the Turkish Embassy assumed the role of representative office. In this respect, as per the relevant regulation, the embassy was in charge of controlling the project, signing protocols with project managers to outline mutual duties and responsibilities, making the necessary payments, and delivering the project report to the Committee. As such, the embassy’s avoidance of all written documentation is in breach of the principles and modus operandi established by its own regulations.

Overall, it can be said that the Promotion Fund Committee does not meet the criteria of transparency and accountability generally expected from a public agency. The dates when the committee convenes to evaluate the projects are not announced, and the committee members, annual budget, sponsorship priorities and selection criteria are not made public. The sums paid to projects sponsored and the content of the projects are not disclosed officially. In other words, there is no transparency about the distribution of the funds, or about the auditing procedures. Such structural problems make it even harder to reveal and question the state’s violation of the right to artistic expression.

Another important aspect of this case is that the state constantly tries to reproduce its dominant discourse based on the denial of past and ongoing human rights violations such as forced displacement, genocide, political murders, burning of villages, enforced disappearances, rape, and torture through security forces; and does its utmost to silence any expression which contests this discourse. The centenary of the Armenian genocide, 2015, is drawing near. As such, it becomes even more important to demand that the Turkish state be held accountable for this human rights violation.

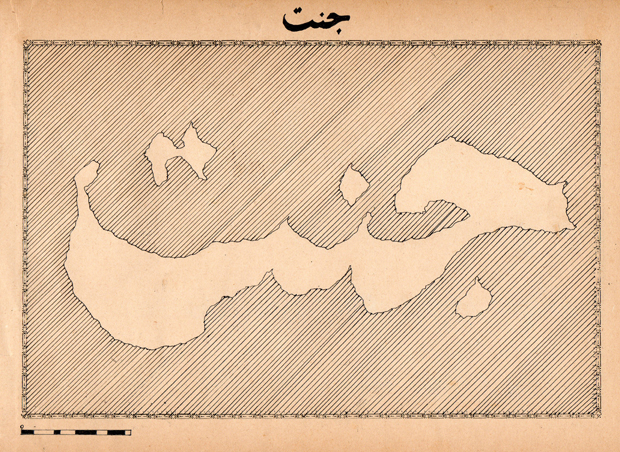

Map of Cennet/Cinnet (Paradise/Possessed Island). Zişan, 1915-1917. Ink on paper, 20×27 cm. Dedicated to the Public Domain

Siyah Bant is a research platform that documents and reports on cases of censorship in arts across Turkey, and shares these with the local and international public. In the context of this work, we wanted to investigate the censorship that occurred at Here Together Now. In accordance with the Right to Information Act, we asked the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, to explain the legal basis of the censorship they imposed on the booklet. In response, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism indicated that Matadero Madrid and curator Manuela Villa were the only authorities in charge of selecting the artists who would participate in the workshops of ARCOmadrid, designating the content of the works to be produced during the workshops, and preparing all printed matter in connection to the event. We were unable to obtain an official statement from curator Manuela Villa, despite several inquiries. Finally, we conducted an interview the artist İz Öztat to understand how the censorship took place, and how she experienced the process.

How did you come to be involved in the exhibition?

I was invited by Manuela Villa, curator of Matadero Madrid, after meeting her in Istanbul. Matadero planned for a residency program and an exhibition project titled Here Together Now to take place concurrently with the 2013 edition of the ARCOmadrid Art Fair that had a section consisting of invited galleries from Turkey. By the time I signed the contract with Matadero Madrid, I knew that the project was partially supported by the Turkish Embassy in Madrid and Turkish Airlines.

Here Together Now was a process that allocated the resources with an emphasis on living and working together. Cristina Anglada (writer), Theo Firmo, Sibel Horada, HUSOS (a collective of architects), Pedagogias Invisibles (art mediation collective), Diego del Pozo Barrius, Dilek Winchester and I had six weeks together, during which we figured out common concerns, negotiated our relationship to the institution’s public, designed the working and exhibition space, collaborated and produced our works.

Can you tell us about the nature of contract with the institution and if there were any limitations indicated as to the nature of your work?

We signed a very detailed contract with Matadero Madrid that laid out the responsibilities of the institution and the artist in relation to the production and authorship of new work but there were no limitations outlined in the contract. I took it for granted that the artist has freedom of expression and institutions do not interfere in the produced content.

The institution was extremely supportive of the project. They were engaged in our discussions and ready to help once we started producing the work.

Could you talk a bit about the work that you prepared for Matadero Madrid?

The work shown in the Here Together Now exhibition was part of an ongoing process, in which I imagine ways to conjure a suppressed past. Since 2010, I have been engaged in an untimely collaboration with Zişan (1894-1970), who is a recently discovered historical figure, a channeled spirit and an alter ego. By inventing an anarchic lineage with a marginalized Ottoman woman, I try to recognize a haunting past and rework it to be able to imagine otherwise. For the exhibition at Matadero Madrid, I produced and exhibited “A Selection from Zişan’s Utopie Folder (1917-1919)” accompanied by works from the “Posthumous Production Series”, in which I depart from Zişan’s work to open a path towards the future in our collaboration. The exhibited work was complemented by a publication with three interviews, which situates the work and builds a discourse around it.

Which aspect of the work was censored? How did the process of censorship occur, and what kind of dilemmas did you face in this process?

Manuela Villa, the curator, met with me in the exhibition space one evening a few days prior to the opening. Officials from the Turkish Embassy had threatened to withdraw their financial support, if the demanded changes were not made. I had to make a decision on the spot and accepted the censorship in the booklet, but not in the publication complementing the work. The exhibition booklet was reprinted and the sentence was changed to “Zişan, born in Istanbul in 1894, is a marginal woman of Armenian descent, who embarks on a European quest.”

As I said before, there was an emphasis on the community we built together during the residency at Matadero and I didn’t want to make a decision alone that would put the whole project at risk. Because of the time constraints, we were only able to meet with the other artists after the opening to discuss the precarious condition that we were all in. The institution didn’t have any signed documents from the Embassy committing to the sponsorship. Everything was communicated verbally and there was no written documentation. I was not able to reach out for a support network to resist the situation, not least due to the immediacy the decision required.

The exhibition booklet that was presented to the embassy was altered but the publication accompanying your work remained unchanged. How did the curator and other artists react to your refusal to change the publication?

I could not stand my ground with regard the exhibition booklet because it concerned everybody in the project. Yet, I was able to take full responsibility of my own work. We were informed that officials from the embassy will visit the show prior to the opening and I was ready to withdraw the work, if there was any interference. Everybody was supportive of my decision.

What happened on the day of the opening? Did you feel the need to prepare yourself?

In the end, none of the officials from the embassy came to the opening or the exhibition. There was no confrontation regarding the work. There might be a few reasons for this that I can think of. Maybe, they felt entitled to interfere with the content of the exhibition booklet because it had the logo of the embassy and could dismiss my publication since it only had the logo of Matadero Madrid. It was not of benefit for the embassy to confront me in a situation that would have made the case public.

As Siyah Bant we inquired both with the curator and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in order to understand how this censoring motion played out. Given that the ministry rejects any responsibility and instead assigns all responsibility to the curator, and that the curator was acting under the duress of loosing all funding last minute, where does this leave you as the artist? How do you make sense of what happened to your work?

Since I accepted the censorship, my only option was making the situation public after the fact. I have been working in cooperation with Siyah Bant since I got back from Madrid. It took a few months to receive an official response from the embassy, which denied all responsibility. We wanted to make the case public after receiving a statement from the curator or the institution. I was unable to receive such a statement, and Siyah Bant is working on that now.

I see it as an experience, in which I was able to test and see the boundaries of government support that is allocated to arts and culture for promoting the country. If you decide to accept this support and challenge official policies, a system of censorship starts to operate.

Next year marks the centenary of the Armenian genocide which will inevitably bring about numerous artistic and cultural reflections on the subject. Given the current climate in Turkey, how confident are you that artistic freedom of expression will be respected?

We are going through a period, in which it is impossible to make predictions about what can happen even the next day. I can only hope that genocide denial at state level comes to an end. I am sure that artists will articulate their own ways of recognising the Armenian Genocide and confronting its denial. You are probably more prepared than I am to predict and know what kinds of mechanisms are at work to limit the production and dissemination of such work.

What would be your recommendations to other artists taking part in cultural events that are supported by the Turkish government?

Based on my experience, I think that artists and art institutions need to act in solidarity in these situations. If there is funding from the Turkish state, the institutions and artists involved need to be aware that the state monitors the content. The various institutions that distribute state funding do not provide written documents about their commitments and communicate their demands mostly in person or by phone. Demanding written documentation at every step is necessary. Artists who are considering to take parts in projects that receive state funding, can demand from the art institutions to be more transparent about the budget and its workings so that they can be prepared to make alternative plans if the state funding does not come through as promised.

If I encountered the same case of censorship now, I would not feel obliged to make a decision immediately and in isolation. I would consult the rest of the group and demand the involvement of the institution.

This article was posted on May 28 2014 at indexoncensorship.org