30 Apr 2021 | Football, News, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Premier League and a coalition of football governing bodies from across the United Kingdom are set to commence a social media blackout from 30 April to 3 May to raise awareness of online racist abuse, but the initiative has raised questions over its end goal.

The Premier League and a coalition of football governing bodies from across the United Kingdom are set to commence a social media blackout from 30 April to 3 May to raise awareness of online racist abuse, but the initiative has raised questions over its end goal.

Clubs, players and governing bodies have called for implementation of the contentious Online Harms Bill (also known as the Online Safety Bill), which will impose regulation on social media companies in order to ensure they remove hateful speech online. They hope the blackout will draw awareness and support of the issue.

The legislation has been criticised as the bill will introduce several key points that a number of free expression groups, including Index, believe to be regressive and will impact on people’s free speech online.

This includes the definition of terms such as “legal but harmful”, which will classify some speech as legal offline but illegal online, meaning there would be inconsistency within the UK system of law.

The Professional Footballers Association (PFA), however, are in strong support of the bill. In a statement they said they hoped social media companies would be held “more accountable”.

“While football takes a stand, we urge the UK Government to ensure its Online Safety Bill will bring in strong legislation to make social media companies more accountable for what happens on their platforms, as discussed at the DCMS Online Abuse roundtable earlier this week,” they said. “We will not stop talking about this issue and will continue to work with the government in ensuring that the Online Safety Bill gives sufficient regulatory and supervisory powers to Ofcom. Social media companies need to be held accountable if they continue to fall short of their moral and social responsibilities to address this endemic problem.”

Index’s CEO Ruth Smeeth has questioned using the bill as a solution to targeting racism, as well as the use of a blackout.

“No one who has spent any time on social media could deny the fact that there is a real problem, with abuse, racism and misogyny,” she said. “The nature of social media platforms seems to bring out the worst in too many people and empower hate from every corner. The question is, though, how to fix it.”

“This is more than about what platforms allow on their sites, it’s about the culture that has been allowed to thrive online. We are all responsible for it, so we all need to work together to fix it as we can’t legislate for cultural change. I understand why the PFA wants to boycott social media platforms – but we saw only last year when others did the same because of antisemitism, boycotts deliver only temporary respite, the haters are still hating. We all deserve better.”

The blackout will see a period of silence on social media to symbolise clubs and governing bodies coming together against the serious issue of racism in football, though some believe the action to be counter-productive and may discourage those affected from speaking out, or removing a place for discourse where people can debate such issues.

Editor of football website These Football Times, Omar Saleem, released a statement explaining why they won’t be joining the blackout over the weekend saying clubs need to take “genuine action”, “not the weekend off”, but also called for social media companies to be held accountable.

“Silence is not the answer. I truly believe that. As a minority in football, that’s my opinion,” he said. “Racism cannot be fought by white-led social media teams suggesting we go silent for the weekend during some of the quietest times on those platforms.”

“Instead of silence, we need action. We need voices to speak louder than ever, programmes that educate and organise. We needed that societally post-George Floyd and we need it in football, too. We need clubs to take genuine action – not the weekend off.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also like to read” category_id=”581″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

28 Apr 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 50.01 Spring 2021

Author

Ma Jian is an award-winning Chinese writer. His latest novel is China Dream. His work is banned in China

Singer

Gelareh Sheibani was born in Iran and took keyboard lessons as a youngter. She found a passion for singing in her teenage years but solo singing in the country was not permitted. After the release of the video for her song Nagoo Tanhaei and the follow-up she was arrested and prosecuted. She later left the country and now lives in Turkey

Journalist

Sarah Sands is Chair of the Gender Equality Advisory Council for G7 and a board member of Index on Censorship. Sands was the former editor of BBC’s Today programme

15 Jan 2021 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image="116027" img_size="full"][vc_column_text]Irony - a situation in which something which was intended to have a particular result has the opposite or a very different one

Censored - suppressed, altered or deleted as objectionable

Words are important and while language is ever evolving some words have had the same meaning for decades, even centuries, and there are simply no excuses for misrepresenting them to try and fit your political worldview. Words have status, they have legal bearing and they are also a thing of beauty enabling us to communicate with each other.

This week we saw the ultimate unintentionally ironic political statement during the debate in the House of Representatives concerning Donald Trump’s second impeachment. Rep Marjorie Taylor Greene, a freshman Republican congresswoman from Georgia, stood up to defend the rhetoric of the president, speaking from the US Capitol, from the chamber of Congress, the home of US democracy, on live television and while being live streamed around the world, with a face mask which read “CENSORED”.

Perhaps it was a veiled reference to Trump’s removal from Twitter? But at that very moment, the congresswoman herself, with her words and her world view being heard by literally millions of people and recorded for posterity in both the media and the Congressional Record, was not being censored. Her voice wasn’t being limited, she wasn’t being forced to restrict her language or caveat her political position. She is fortunate to live in a country where free speech is still both protected and valued. And to suggest otherwise undermines the global fight for the right to free speech in repressive regimes.

Senator Josh Hawley has had his book contract cancelled by Simon & Schuster. They said “[a]fter witnessing the disturbing, deadly insurrection that took place on Wednesday in Washington, D.C. We did not come to this decision lightly. As a publisher it will always be our mission to amplify a variety of voices and viewpoints; at the same time we take seriously our larger public responsibility as citizens, and cannot support Senator Hawley after his role in what became a dangerous threat to our democracy and freedom.”

Hawley is claiming that he is being cancelled, that his constitutional right to free speech is being attacked and that he is suing. We know that because Hawley was featured in nearly every news outlet which covers the USA, both foreign and domestic. Hawley remains a senator, he has the right to speak to his nation in every sitting outlining his priorities and world view. His words were published this week in an op-ed in his local media. He hasn’t been silenced or cancelled, his lucrative book deal has. And even if that sets a bad precedent – a debate we will explore further at Index over the coming months – it is not the same thing.

Our right to free speech is precious. It is something that we need to cherish. Not abuse. And we need to be honest about when it is and is not being threatened. It is being threatened in Belarus, where our own correspondent Andrei Aliaksandrau has just been arrested by the regime. It is under threat in Egypt where according to the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 60,000 political prisoners are incarcerated. It is nonexistent in Xinjiang province, China, where millions of Uighurs have been sent to re-education camps. It is not being threatened in the USA – it may be being challenged but these words mean different things.

I believe passionately about our right to free speech. I think everybody has the right to speak, to argue their position, to tell their stories. But there is a difference from having the right to speak and the right to be heard. Simply put you don’t have the latter, it is not a universal right, which can be unjust and for some incredibly damaging but it’s the reality we live in.

This brings me to the other controversy of the week, which warrants a great deal of debate and conversation. Something Index is going to launch in the coming weeks – the suspension of Trump from his social media accounts. Most online platforms are corporate entities, who balance responsibilities to defend free speech and to protect their users. They have a duty of care to their customers as well as to their corporate reputations. They also facilitate a great deal of our national and personal conversations. And they have made the remarkable decision to remove the President of the United States from their sites. They had the right to do this, but the question is should they have removed him and more importantly who decided he shouldn’t be there?

It was not a decision that was taken lightly. “I do not celebrate or feel pride in our having to ban @realDonaldTrump from Twitter, or how we got here. After a clear warning we’d take this action, we made a decision with the best information we had based on threats to physical safety both on and off Twitter. Was this correct?” wrote CEO of Twitter Jack Dorsey.

In his thoughtful thread on the action he wrote: “Having to take these actions fragment the public conversation. They divide us. They limit the potential for clarification, redemption, and learning. And sets a precedent I feel is dangerous: the power an individual or corporation has over a part of the global public conversation.”

As Dorsey himself acknowledges we need to explore what role these companies really play in our society. Are they merely platforms enabling us to engage within a framework they determine? Are they publishers responsible for every word on their sites? Do they govern the public space or merely facilitate it? And do we know what they are doing? Their actions can determine who speaks and who is heard. We need a really robust conversation about where the red lines should be on online content and what is or isn’t acceptable. These questions have been circulating for a while but have never felt more crucial to be addressed than this week. These are the questions that will define our online presence in the years ahead, so we need answers now.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

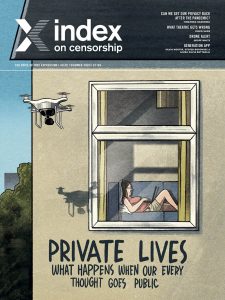

17 Jun 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Contents, Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text="With contributions from Katherine Parkinson, David Hare, Marina Lalovic, Geoff White and Timandra Harkness"][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It's a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question people in Turkey are really concerned about, as many feel the home was the last refuge for them for privacy, but now contact tracing apps might rid them of that. It's a similar case for those in China, and the journalist Tianyu M Fang speaks about his own, haphazard experience of using a contact tracing app there. We also have an article from Uganda on the government spies that are everywhere, plus tech experts talking about just how much power apps like Zoom and tech like drones have.

In our In Focus section, we interview journalists in Serbia, Hungary and Kashmir who are trying to report the truth in places where the truth can be as dangerous, if not more, than Covid-19. And we have an interview with and poet from the playwright David Hare.

We have a very special culture section in this issue. Three playwrights have written short plays for the magazine around the theme of pandemics. V (formerly Eve Ensler), the author of The Vagina Monologues, takes you to the aftermath of a nuclear disaster; Katherine Parkinson of The IT Crowd writes about online dating during quarantine; Lebanese playwright Lucien Bourjeily is inspired by recent events in his country in his chilling look at protest right now.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text="Special Report"][vc_column_text]

Back-up plan by Timandra Harkness: Don’t blindly give away more freedoms than you sign up for in the name of tackling the epidemic. They’re hard to reclaim

The eyes of the storm by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Spies are on the streets of Uganda making sure everyone abides by Covid-19 rules. They’re spying on political opposition too. A dispatch from Kampala

Zooming in on privacy concerns by Adam Aiken: Video app Zoom is surging in popularity. In our rush to stay connected, we need to make security checks and not reveal more than we think

Seeing what's around the corner by Richard Wingfield: Facial recognition technology may be used to create immunity “passports” and other ways of tracking our health status. Are we watching?

Don't just drone on by Geoff White: If drones are being used to spy on people breaking quarantine rules, what else could they be used for? We investigate

Sending a red signal by Tianyu M Fang: When a contact tracing app went wrong a journalist was forced to stay in their home in China

The not so secret garden by Tom Hodgkinson: Better think twice before bathing naked in the backyard. It’s not just your neighbours that might be watching you. Where next for privacy?

Hackers paradise by Stephen Woodman: Hackers across Latin America are taking advantage of the current crisis to access people’s personal data. If not protected it could spell disaster

Italy's bad internet connection by Alessio Perrone: Italians have one of the lowest levels of digital skills in Europe and are struggling to understand implications of the new pandemic world

Less than social media by Stefano Pozzebon: El Salvador’s new leader takes a leaf out of the Trump playbook to use Twitter to crush freedoms

Nowhere left to hide by Kaya Genç: Privacy has been eroded in Turkey for many years now. People fear that tackling Covid-19 might take away their last private free space

Open book? by Somak Ghoshal: In India, where people are forced to download a tracking app to get paid, journalists are worried about it also being used to access their contacts

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text="In Focus"][vc_column_text]

Knife-edge politics by Marina Lalovic: An interview with Serbian journalist Ana Lalic, who forced the Serbian government to do a U-Turn

Stage right (and wrong) by Jemimah Steinfeld: The playwright David Hare talks to Index about a very 21st century form of censorship on the stage. Plus a poem of Hare’s published for the first time

Inside story: Hungary's media silence by Viktória Serdült: What’s it like working as a journalist under the new rules introduced by Hungary’s Viktor Orbán? How hard is it to report?

Life under lockdown: A Kashmiri Journalist by Bilal Hussain: A Kashmiri journalist speaks about the difficulties - personal and professional - of living in the state with an internet shutdown during lockdown

The truth will out by John Lloyd: Journalists need to challenge themselves and fight for media freedoms that are being eroded by autocrats and tech companies

Extremists use virus to curb opposition by Laura Silvia Battaglia: Covid-19 is being used by religious militia as a recruitment tool in Yemen and Iraq. Speaking out as a secular voice is even more challenging

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text="Culture"][vc_column_text]

Masking the truth by V: The writer of The Vagina Monologues (formerly known as Eve Ensler) speaks to Index about attacks on the truth. Plus a new version of her play about living in a nuclear wasteland

Time out by Katherine Parkinson: The star of The IT Crowd discusses online dating and introduces her new play, written for Index, that looks at love and deception online

Life in action by Lucien Bourjeily: The Lebanese director talks to Index about how police brutality has increased in his country and how that informed the story of his new play, published here for the first time

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text="Index around the world"][vc_column_text]

Putting abuse on the map by Orna Herr: The coronavirus crisis has seen a huge rise in media attacks. Index has launched a map to track these

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text="Endnote"][vc_column_text]

Forced out of the closet by Jemimah Steinfeld: As people live out more of their lives online right now, our report highlights how LGBTQ dating apps can put people’s lives at risk

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width="1/3"][vc_custom_heading text="Subscribe"][vc_column_text]In print, online, in your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship's projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width="1/3"][vc_custom_heading text="Read"][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width="1/3"][vc_custom_heading text="Read"][vc_column_text]The playwright Arthur Miller wrote an essay for Index in 1978 entitled The Sin of Power. We reproduce it for the first time on our website and theatre director Nicholas Hytner responds to it in the magazine

READ HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width="1/3"][vc_custom_heading text="Listen"][vc_column_text]In the Index on Censorship autumn 2019 podcast, we focus on how travel restrictions at borders are limiting the flow of free thought and ideas. Lewis Jennings and Sally Gimson talk to trans woman and activist Peppermint; San Diego photojournalist Ariana Drehsler and Index's South Korean correspondent Steven Borowiec

LISTEN HERE[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

The Premier League and a coalition of football governing bodies from across the United Kingdom are set to commence a social media blackout from 30 April to 3 May to raise awareness of online racist abuse, but the initiative has raised questions over its end goal.

The Premier League and a coalition of football governing bodies from across the United Kingdom are set to commence a social media blackout from 30 April to 3 May to raise awareness of online racist abuse, but the initiative has raised questions over its end goal.

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question

The Summer 2020 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at just how much of our privacy we are giving away right now. Covid-19 has occurred at a time when tech giants and autocrats have already been chipping away at our freedoms. Just how much privacy is left and how much will we now lose? This is a question