24 Mar 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 49.01 Spring 2020

Director

Émerson Maranhão is a Brazilian director and filmmaker, who has directed the short film Aqueles Dois, about two transgender men, amongst others

Writer

An award-winning Libyan academic and writer, Najwa Bin Shatwan has written three novels, a collection of short stories, plays and contributions to anthologies

Historian

Tom Holland is a writer and historian, who has published a range of bestselling books. He specialises in classical and medieval history

10 Dec 2019 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 48.04 Winter 2019

Poet

Tammy Lai-ming Ho is an award-winning poet, translator and academic who is documenting the Hong Kong protests through poetry

Writer

Author of the bestselling hit humour titles The Beautiful Poetry of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, Life Coach, Rob Sears is a writer based in London

Opera singer

Jamie Barton is an American opera singer, who performs globally. She headllined Last Night of the Proms at Royal Albert Hall this summer

13 Sep 2019 | Events

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text] What can EU and national governments do to stop disinformation originating from foreign actors and domestic extremists? Could new rules pose a future risk for traditional media at the hands of populist leaders? What role does the media play in maintaining unity and liberalism in Europe? What limits – if any – can be extended to social media?

What can EU and national governments do to stop disinformation originating from foreign actors and domestic extremists? Could new rules pose a future risk for traditional media at the hands of populist leaders? What role does the media play in maintaining unity and liberalism in Europe? What limits – if any – can be extended to social media?

Join Index chief executive Jodie Ginsberg for a panel discussion.

Part of FT Future of News Europe conference

Book tickets here[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]When: Tuesday November 26, 4.10pm

Where: Amsterdam[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

12 Sep 2019 | Magazine, News, Volume 48.03 Autumn 2019

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Editor-in-chief Rachael Jolley argues in the autumn 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine that travel restrictions and snooping into your social media at the frontier are new ways of suppressing ideas” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

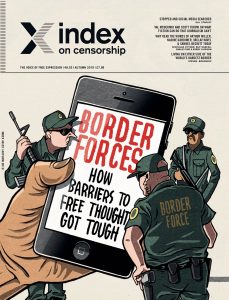

Border Forces – how barriers to free thought got tough

Travelling to the USA this summer, journalist James Dyer, who writes for Empire magazine, says he was not allowed in until he had been questioned by an immigration official about whether he wrote for those “fake news” outlets.

Also this year, David Mack, deputy director of breaking news at Buzzfeed News, was challenged about the way his organisation covered a story at the US border by an official.

He later received an official apology from the Customs and Border Protection service for being questioned on this subject, which is not on the official list of queries that officers are expected to use.

As we go to press, the UK Foreign Office updated its advice for travellers going between Hong Kong and China warning that their electronic devices could be searched.

This happened a day after a Sky journalist had his belongings, including photos, searched at Beijing airport. US citizen Hugo Castro told Index how he was held for five hours at the USA-Mexico border while his mobile phone, photos and social media were searched.

This kind of behaviour is becoming more widespread globally as nations look to surveil what thoughts we have and what we might be writing or saying before allowing us to pass.

This ends with many people being so worried about the consequences of putting pen to paper that they don’t. They fret so much about being prevented from travelling to see a loved one or a friend, or going on a work trip, that they stop themselves from writing or expressing dissent.

If the world spins further in this direction we will end up with a global climate of fear where we second-guess our desire to write, tweet, speak or protest, by worrying ourselves down a timeline of what might happen next.

So what is the situation today? Border officials in some countries already seek to find out about your sexual orientation via an excursion into your social media presence as part of their decision on whether to allow you in.

Travel advisors who offer LGBT travel advice suggest not giving up your passcodes or passwords to social media accounts. One says that, before travelling, people can look at hiding their social media posts from people they might stay within the destination country. Digital security expert Ela Stapley suggests going further and having an entirely separate “clean” phone for travelling.

These actions at borders have not gone unnoticed by technology providers. The big dating apps are aware that information to be found in their spaces might also prove of interest to immigration officials in some countries.

This summer, Tinder rolled out a feature called Traveller Alert – as Mark Frary reports on – which hides people’s profiles if they are travelling to countries where homosexuality is illegal. Borders are getting bigger, harder and tougher.

It is not just about people travelling, it’s also about knowledge and ideas being stopped. As security services and governments get more tech-savvy, they see more and more ways to keep track of the words that we share. Surely there’s no one left out there who doesn’t realise the messages in their Gmail account are constantly being scanned and collected by Google as the quid pro quo for giving you a free account?

Google is collecting as much information as it can to help it compile a personal profile of everyone who uses it. There’s no doubt that if companies are doing this, governments are thinking about how they can do it too – if they are not already.

And the more they know, the more they can work out what they want to stop.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Border officials in some countries already seek to find out about your sexual orientation via an excursion into your social media presence as part of their decision on whether to allow you in” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

In democracies such as the UK, police are already experimenting with facial recognition software. Recently, anti-surveillance organisation Big Brother Watch discovered that private shopping centres had quietly started to use facial recognition software without the public being aware.

It feels as though everywhere we look, everyone is capturing more and more information about who we are, and we need to worry about how this is being used.

One way that this information can be used is by border officials, who would like to know everything about you as they consider your arrival. What we’ve learned in putting this special issue together is that we need to be smart, too. Keep an eye on the laws of the country you are travelling to, in case legislation relating to media, communication or even visas change.

Also, have a plan about what you might do if you are stopped at a border. One of the big themes of this magazine over the years is that what happens in one country doesn’t stay in one country. What has become increasingly obvious is that nation copies nations, and leader after leader spots what is going on across the way and thinks: “I could use that too.”

We saw troll factories start in Mexico with attempts to discredit journalists’ reputations five years ago, and now they are widespread. The idea of a national leader speaking directly to the public rather than giving a press conference, and skipping the “need” to answer questions, was popular in Latin America with President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, of Argentina, and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez.

A few years later, national leaders around the world have grabbed the idea and run with it. It’s so we don’t have to filter it through the media, say the politicians. While there’s nothing wrong, of course, with having town hall chats with the public, one has a sneaking suspicion that another motivation might be dodging any difficult questions, especially if press conferences then get put on hold. Again, Latin America saw it first.

Given this trend, we can expect that when one nation starts asking for access to your social media accounts before they give you a visa, others are sure to follow. The border issue is broader than this, of course. Migration and immigration are issues all over the world right now, topping most political agendas, along with security and the economy. Therefore, governments are seeking to reduce immigration and restrict who can enter their countries – using a variety of methods.

In the USA and the UK, artists, academics, writers and musicians are finding visas harder to come by. As our US contributing editor, Jan Fox, reports, this has led to an opera singer removing posts from Facebook because she worries about her visa application, and academics self-censoring their ideas in case it limits them from studying or working in the USA. Where does this leave free expression? Less free than it should be, certainly. This is not the only attack on freedom of expression. Making it more difficult for outsiders to travel to these countries means stories about life in Yemen, Syria and Iran, for instance, may not be heard.

We don’t hear firsthand what it is like, and our knowledge shrinks. This policy surely reached a limit when Kareem Abeed, the Syrian producer of an Oscar-nominated documentary about Aleppo, was initially refused a visa to at-tend the Oscar ceremony. Meanwhile, UK festival directors are calling for their government to change its attitude and warn that artists are already excluding the UK from their tours.

One person who knew the value of getting information out beyond the borders of the country he lived in was a former editor of this magazine, Andrew Graham-Yooll, and we honour his work in this issue. His recent death gave us a chance to review his writing for us and for others. A consummate journalist, Graham-Yooll continued to write and report until just weeks before his death, and I know he would have had his typing fingers at the ready for a critique of what is happening in the Argentinian election right now.

Graham-Yooll took the job of editor of Index on Censorship in 1989, after being forced to leave his native Argentina because of his reporting. He had been smuggling out reports of the horrifying things that were happening under the dictatorship, where people who were activists, journalists and critics of the government were “disappearing” – a soft word that means they were being murdered. Some pregnant women were taken prisoner until they gave birth. Their babies were taken from them and given to military or government-friendly families to adopt, while the mothers were drugged and then dropped to their death, from airplanes, at sea.

Many of the appalling details of what happened under the authoritarian dictatorship only became clear after it fell, but Graham-Yooll took measures to smuggle out as many details as he could, to this publication and others, until he and his family were in such danger he was forced to leave Argentina and move to the UK.

Throughout history the powerful have always attempted to suppress information they didn’t want to see the light. We are in yet another era where this is on the rise.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship magazine. She tweets @londoninsider. This article is part of the latest edition of Index on Censorship magazine, with its special report on border forces

Index on Censorship’s autumn 2019 issue is entitled Border forces: how barriers to free thought got tough

Look out for the new edition in bookshops, and don’t miss our Index on Censorship podcast, with special guests, on Soundcloud.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”How barriers to free thought got tough” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2019%2F09%2Fmagazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The autumn 2019 Index on Censorship magazine looks at borders round the world and how barriers to free thought got tough[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”108826″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/09/magazine-border-forces-how-barriers-to-free-thought-got-tough/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

What can EU and national governments do to stop disinformation originating from foreign actors and domestic extremists? Could new rules pose a future risk for traditional media at the hands of populist leaders? What role does the media play in maintaining unity and liberalism in Europe? What limits – if any – can be extended to social media?

What can EU and national governments do to stop disinformation originating from foreign actors and domestic extremists? Could new rules pose a future risk for traditional media at the hands of populist leaders? What role does the media play in maintaining unity and liberalism in Europe? What limits – if any – can be extended to social media?