12 May 2016 | mobile, News

Facebook made headlines this week over allegations by former staff that the site tampers with its “what’s trending” algorithm to remove and suppress conservative viewpoints while giving priority to liberal causes.

The news isn’t likely to shock many people. Attempts to control social media activity have been rife since Facebook and Twitter launched in 2006. We are outraged when political leaders ban access to social media, or when users face arrest or the threat of violence for their posts. But it is less clear cut when social media companies remove content they deem in breach of their terms and conditions, or move to suspend or ban users they deem undesirable.

“Legally we have no right to be heard on these platforms, and that’s the problem,” Jillian C. York, director for international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, tells Index on Censorship. “As social media companies become bigger and have an increasingly outsized influence in our lives, societies, businesses and even on journalism, we have to think outside of the law box.”

Transparency rather than regulation may be the answer.

Back in November 2015, York co-founded Online Censorship, a user-generated platform to document content takedowns on six social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Flickr, Google+ and YouTube), to address how these sites moderate user-generated content and how free expression is affected online.

Back in November 2015, York co-founded Online Censorship, a user-generated platform to document content takedowns on six social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Flickr, Google+ and YouTube), to address how these sites moderate user-generated content and how free expression is affected online.

Online Censorship’s first report, released in March 2016, stated: “In the United States (where all of the companies covered in this report are headquartered), social media companies generally reserve the right to determine what content they will host, and they do not consider their policies to constitute censorship. We challenge this assertion, and examine how their policies (and the enforcement thereof) may have a chilling effect on freedom of expression.”

The report found that Facebook is by far the most censorious platform. Of 119 incidents, 25 were related to nudity and 16 were due to the user having a false name. Further down the list were content removed on grounds of hate speech (6 reports) and harassment (2).

“I’ve been talking with these companies for a long time, and Facebook is open to the conversation, even if they haven’t really budged on policies,” says York. If policies are to change and freedom of expression online strengthened, “we have to keep the pressure on companies and have a public conversation about what we want from social media”.

Critics of York’s point of view could say if we aren’t happy with the platform, we can always delete our accounts. But it may not be so easy.

Recently, York found herself banned from Facebook for sharing a breast cancer campaign. “Facebook has very discriminatory policies toward the female body and, as a result, we see a lot of takedowns around that kind of content,” she explains.

Even though York’s Facebook ban only lasted one day, it proved to be a major inconvenience. “I couldn’t use my Facebook page, but I also couldn’t use Spotify or comment on Huffington Post articles,” says York. “Facebook isn’t just a social media platform anymore, it’s essentially an authorisation key for half the web.”

For businesses or organisations that rely on social media on a daily basis, the consequences of a ban could be even greater.

Facebook can even influence elections and shape society. “Lebanon is a great example of this, because just about every political party harbours war criminals but only Hezbollah is banned from Facebook,” says York. “I’m not in favour of Hezbollah, but I’m also not in favour of its competitors, and what we have here is Facebook censors meddling in local politics.”

York’s colleague Matthew Stender, project strategist at Online Censorship, takes the point further. “When we’re seeing Facebook host presidential debates, and Mark Zuckerberg running around Beijing or sitting down with Angela Merkel, we know it isn’t just looking to fulfil a responsibility to its shareholders,” he tells Index on Censorship. “It’s taking a much stronger and more nuanced role in public life.”

It is for this reason that we should be concerned by content moderators. Worryingly, they often find themselves dealing with issues they have no expertise in. A lot of content takedown reported to Online Censorship is anti-terrorist content mistaken for terrorist content. “It potentially discourages those very people who are going to be speaking out against terrorism,” says York.

Facebook has 1.5 billion users, so small teams of poorly paid content moderators simply cannot give appropriate consideration to all flagged content against the secretive terms and conditions laid out by social media companies. The result is arbitrary and knee-jerk censorship.

“I have sympathy for the content moderators because they’re looking at this content in a split second and making a judgement very, very quickly as to whether it should remain up or not,” says York. “It’s a recipe for disaster as its completely not scalable and these people don’t have expertise on things like terrorism, and when they’re taking down.”

Content moderators — mainly based in Dublin, but often outsourced to places like the Philippines and Morocco — aren’t usually full-time staff, and so don’t have the same investment in the company. “What is to stop them from instituting their own biases in the content moderation practices?” asks York.

One development Online Censorship would like to see is Facebook making public its content moderation guidelines. In the meantime,the project will continue to strike at transparency by providing crowdsourced transparency to allow people to better understand what these platforms want from us.

These efforts are about getting users to rethink the relationship they have with social media platforms, say York. “Many treat these spaces as public, even though they are not and so it’s a very, very harsh awakening when they do experience a takedown for the first time.”

27 Apr 2016 | Magazine, mobile, Volume 45.01 Spring 2016

Reporters shouldn’t forget old techniques for checking information. Image: Alex Steffler/ Flickr /Creative Commons

Can you stand it up? Those five words were the ones I probably uttered more than any other when editing a daily newspaper. Excited reporters would be fed a diet of rumours: a member of parliament has left his wife, the chief constable has been suspended. These snippets would then be thrown into the daily news conference. And, with some exaggerated world-weariness, I would ask the key question. Can you stand it up? I never heard about half of the stories again.

Our advantage was that when a lead emerged at midday, we had nine hours to stand it up. If we couldn’t make it watertight we could give ourselves another 24 hours. In today’s digital world the pressure is on to push the button as soon any unsubstantiated tale flashes across our Twitter feeds. And the rush to publish means half-baked stories, outdated pictures and factual errors appear on websites that should know better. The irony is that verification has never been easier. My staff used to tread a regular path to our library to consult Dod’s Parliamentary Companion, Bartholomew’s Gazetteer and our own cuttings. Now you can check almost everything online. So why don’t we? As Spotlight, the Oscar-winning Hollywood film on investigative journalism shows, sourcing, checking and re-checking is how you nail whether a story stands up. In the world of 24-hour news and digital everything, those traditional techniques should not be forgotten. They include:

- Be suspicious of everything. Take nothing at face-value. Check for vested interests. Trust no-one – even good contacts.

- Your job is to confirm things. If you can’t, try harder. If you really can’t, don’t publish.

- Always go to primary sources. Ask the chief constable if he is being suspended. Ask the authority chairman. If they won’t talk, find the committee members – all of them. When my neighbour was killed the local paper splashed it and got three facts wrong. Nobody from the paper had called the family (or me for that matter). Nobody bothered to make the effort. Shocking.

- Follow the two-sources rule. Get everything verified by at least two trustworthy sources. Ideally on the record.

- Use experts. There are universities, academics, specialists who will flag up credibility issues. Experts also know other experts.

- Every story has a paper trail. There are still archives (try LexisNexis), court papers, Company House, Tracesmart. Has the same mistake been made before?

- Ask yourself the key questions. What else can I look at? Who else can I talk to? Is it balanced? Did I write the headline first and make the story fit?

- Make sure the readers understand what is opinion and what is fact. And that includes the headline.

- Sweat the small stuff. Dates, spelling, names, figures, statistics. Don’t forget the who, what, why, where, when and how.

- Evaluate the risk. There are times when with all the rigorous checking, a story might still only be 99%. If instinct and public interest tell you to publish – pass it to the editor. That is what he or she is paid for. And, with the other nine rules followed thoroughly, hopefully the editor won’t need to ask the key question.

Peter Sands is the former editor of UK daily newspaper the Northern Echo and runs media consultancy Sands Media Services. This story is an extract from a longer report by First Draft’s Alastair Reed about the importance of verification to stop the spread of hoaxes and propaganda online.

You can read the full feature in the current issue of Index on Censorship magazine (see subscription details here)

17 Jun 2015 | Azerbaijan News, mobile, News

Governments don’t really like coming across as authoritarian. They may do very authoritarian things, like lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro democracy campaigners, but they’d rather these people didn’t talk about it. They like to present themselves as nice and human rights-respecting; like free speech and rule of law is something their countries have plenty of. That’s why they’re so keen to stress that when they do lock up journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners, it’s not because they’re journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. No, no: they’re criminals you see, who, by some strange coincidence, all just happen to be journalists and activists and human rights lawyers and pro-democracy campaigners. Just look at the definitely-not-free-speech-related charges they face.

1) Azerbaijan: “incitement to suicide”

Khadija Ismayilova is one of the government critics jailed ahead of the European Games.

Azerbaijani investigative journalist Khadija Ismayilova was arrested in December for inciting suicide in a former colleague — who has since told media he was pressured by authorities into making the accusation. She is now awaiting trial for “tax evasion” and “abuse of power” among other things. These new charges have, incidentally, also been slapped on a number of other Azerbaijani human rights activists in recent months.

2) Belarus: participation in “mass disturbance”

Belorussian journalist Irina Khalip was in 2011 given a two-year suspended sentence for participating in “mass disturbance” in the aftermath of disputed presidential elections that saw Alexander Lukashenko win a fourth term in office.

3) China: “inciting subversion of state power”

Chinese dissident Zhu Yufu in 2012 faced charges of “inciting subversion of state power” over his poem “It’s time” which urged people to defend their freedoms.

4) Angola: “malicious prosecution”

Journalist and human rights activist Rafael Marques de Morais (Photo: Sean Gallagher/Index on Censorship)

Rafael Marques de Morais, an Angolan investigative journalist and campaigner, has for months been locked in a legal battle with a group of generals who he holds the generals morally responsible for human rights abuses he uncovered within the country’s diamond trade. For this they filed a series of libel suits against him. In May, it looked like the parties had come to an agreement whereby the charges would be dismissed, only for the case against Marques to unexpectedly continue — with charges including “malicious prosecution”.

5) Kuwait: “insulting the prince and his powers”

Kuwaiti blogger Lawrence al-Rashidi was in 2012 sentenced to ten years in prison and fined for “insulting the prince and his powers” in poems posted to YouTube. The year before he had been accused of “spreading false news and rumours about the situation in the country” and “calling on tribes to confront the ruling regime, and bring down its transgressions”.

6) Bahrain: “misusing social media

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

In January nine people in Bahrain were arrested for “misusing social media”, a charge punishable by a fine or up to two years in prison. This comes in addition to the imprisonment of Nabeel Rajab, one of country’s leading human rights defenders, in connection to a tweet.

7) Saudi Arabia: “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”

In late 2014, Saudi women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets, on charges including “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”.

8) Guatemala: causing “financial panic”

Jean Anleau was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing their money from banks.

9) Swaziland: “scandalising the judiciary”

Swazi Human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko and journalist and editor Bheki Makhubu in 2014 faced charges of “scandalising the judiciary”. This was based on two articles by Maseko and Makhubu criticising corruption and the lack of impartiality in the country’s judicial system.

10) Uzbekistan: “damaging the country’s image”

Umida Akhmedova (Image: Uznewsnet/YouTube)

Uzbek photographer Umida Akhmedova, whose work has been published in The New York Times and Wall Street Journal, was in 2009 charged with “damaging the country’s image” over photographs depicting life in rural Uzbekistan.

11) Sudan: “waging war against the state”

Al-Haj Ali Warrag, a leading Sudanese journalist and opposition party member, was in 2010 charged with “waging war against the state”. This came after an opinion piece where he advocated an election boycott.

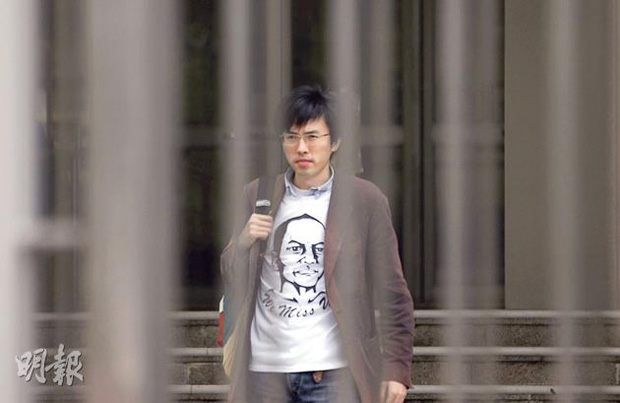

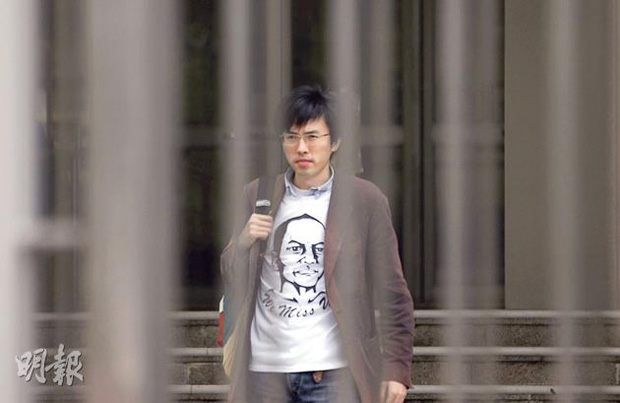

12) Hong Kong: “nuisance crimes committed in a public place”

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

Avery Ng, an activist from Hong Kong, was in 2012 charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place” after throwing a t-shirt featuring a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit.

13) Morocco: compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”

Rachid Nini, a Moroccan newspaper editor, was in 2011 sentenced to a year in prison and a fine for compromising “the security and integrity of the nation and citizens”. A number of his editorials had attempted to expose corruption in the Moroccan government.

This article was originally posted on 17 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

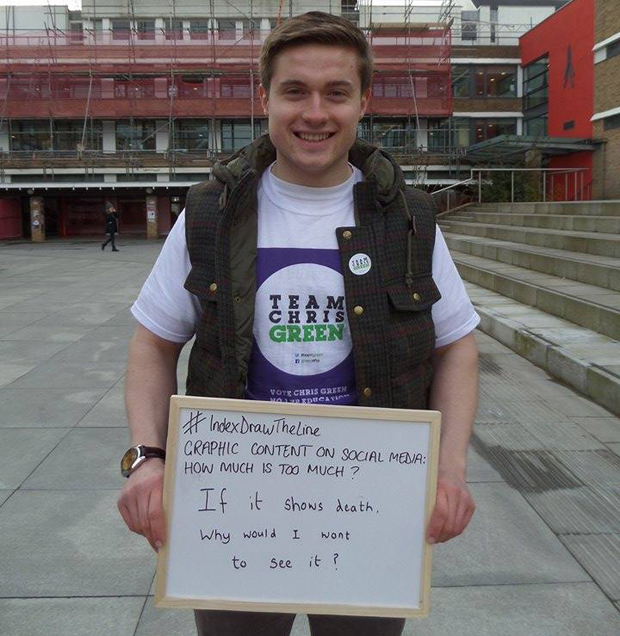

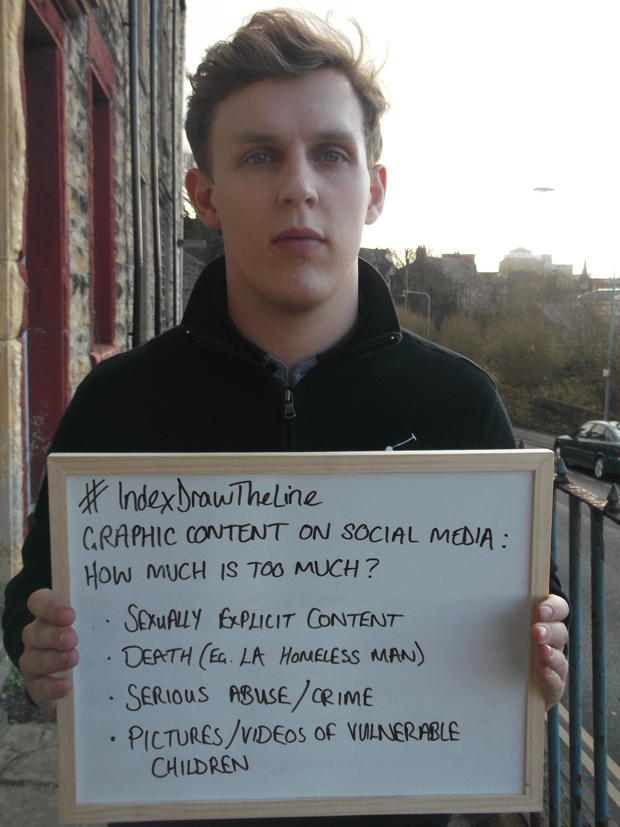

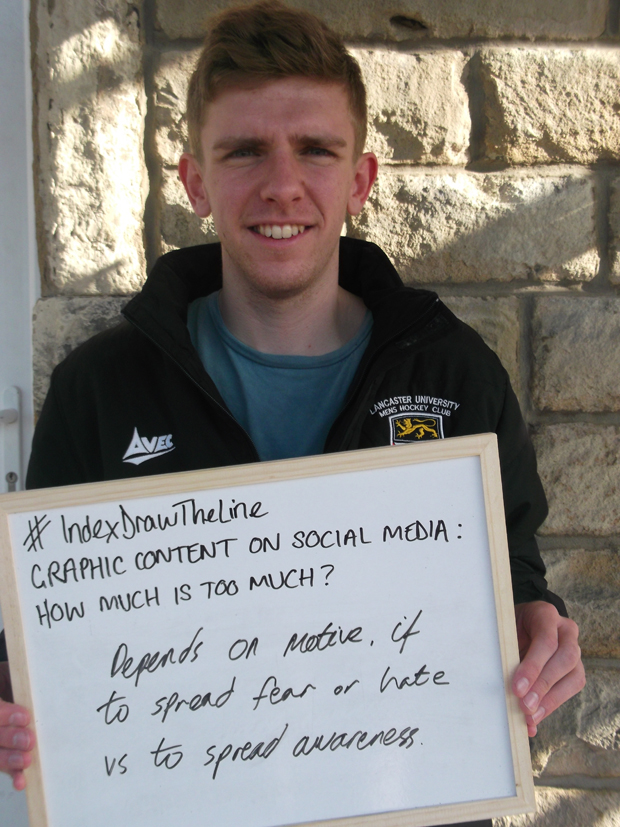

24 Mar 2015 | Draw the Line, mobile

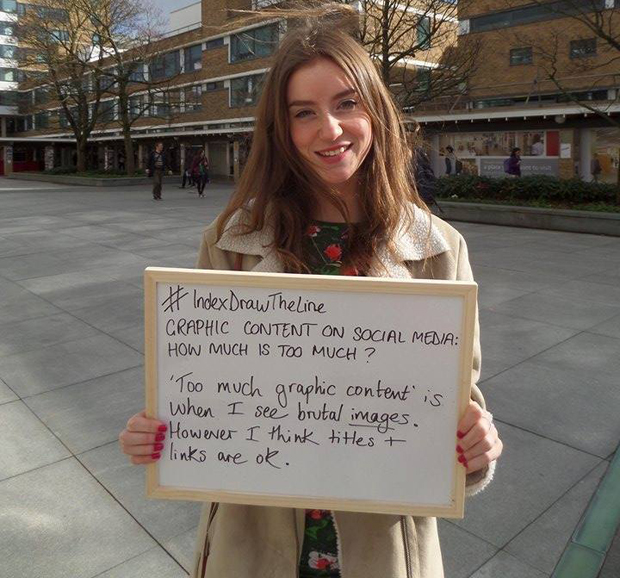

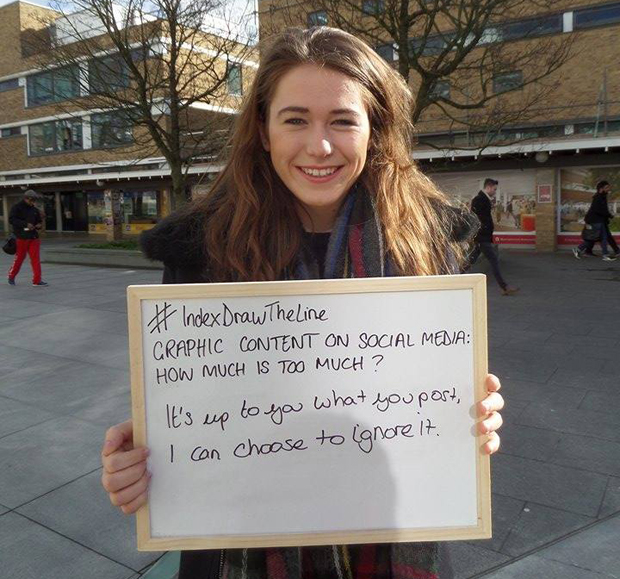

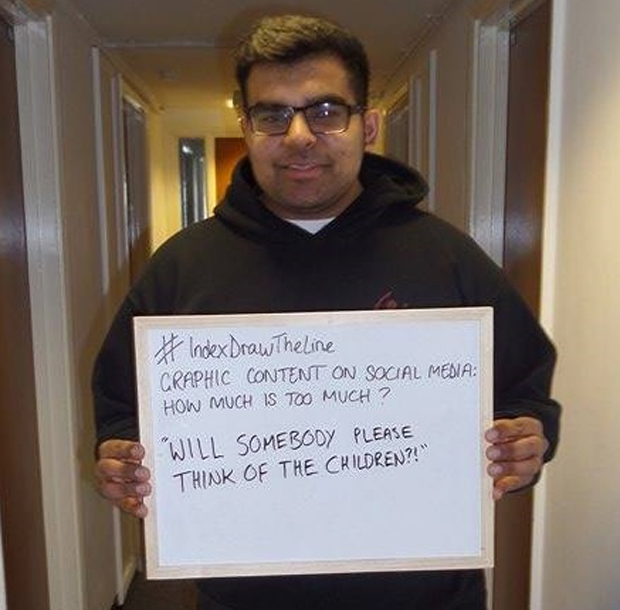

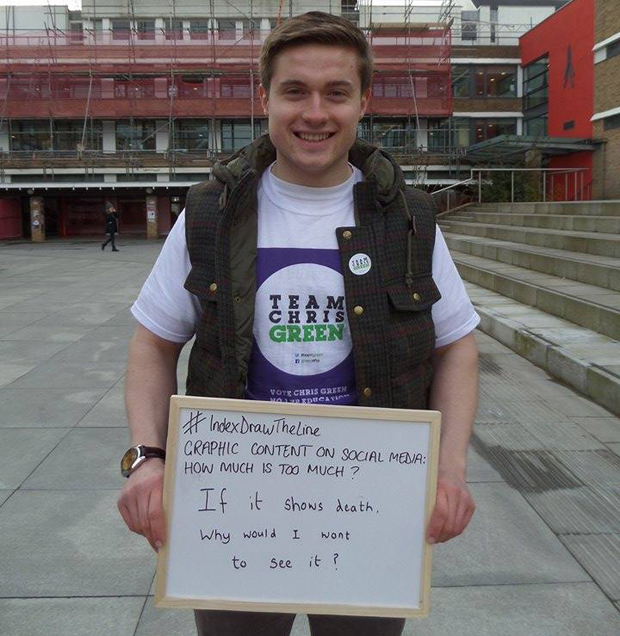

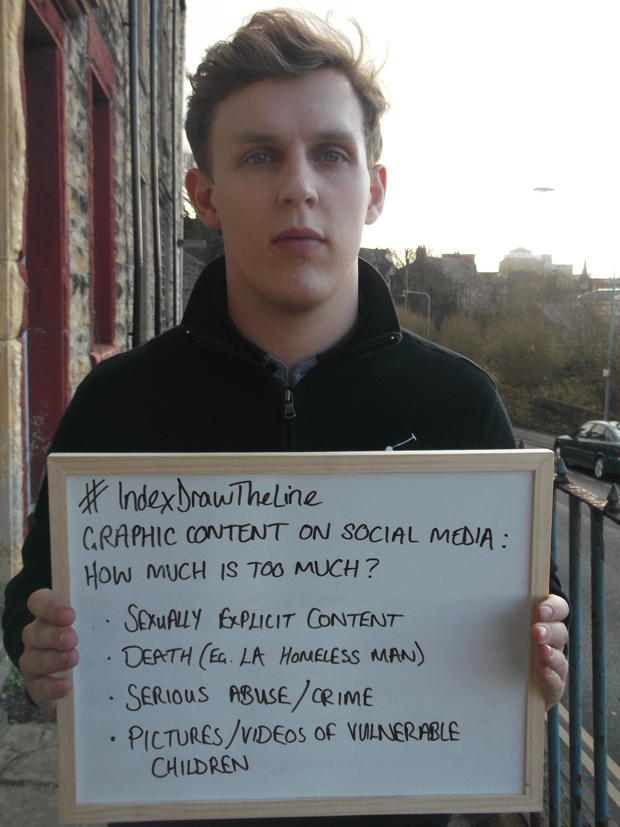

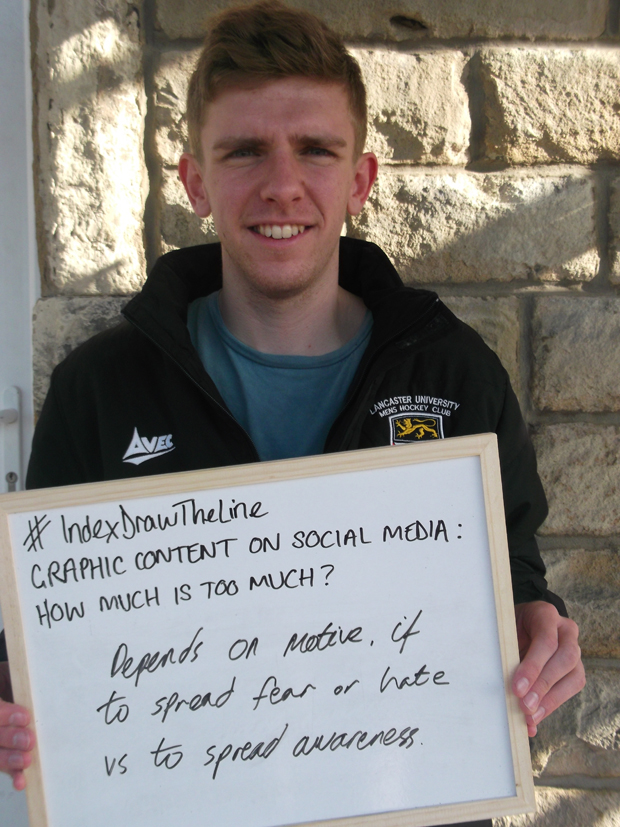

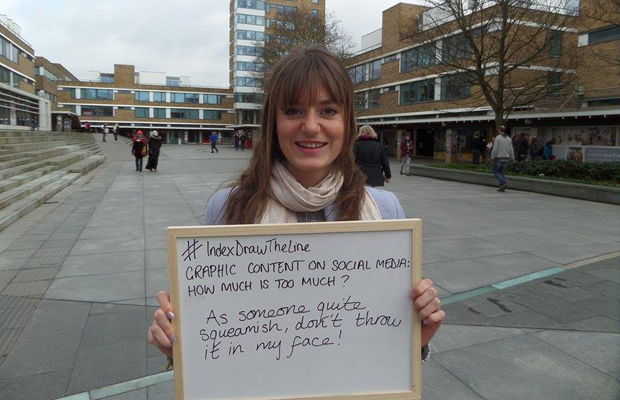

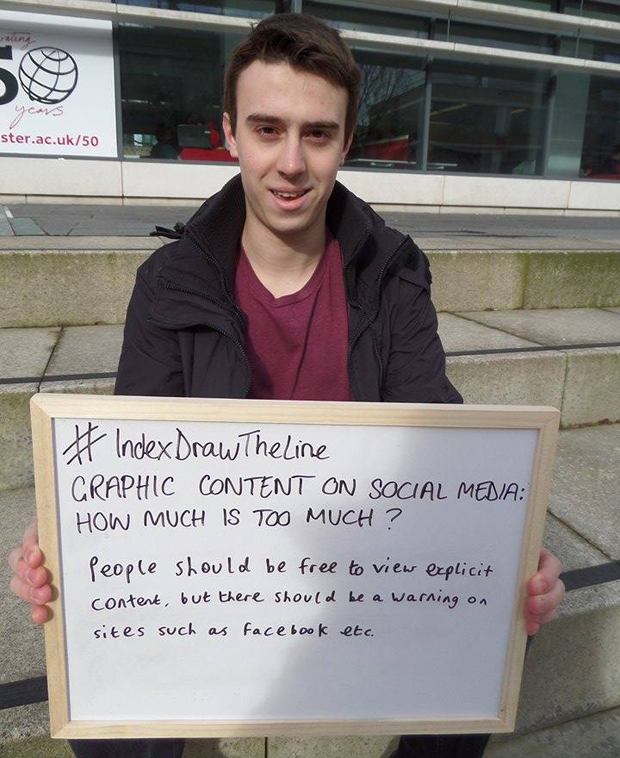

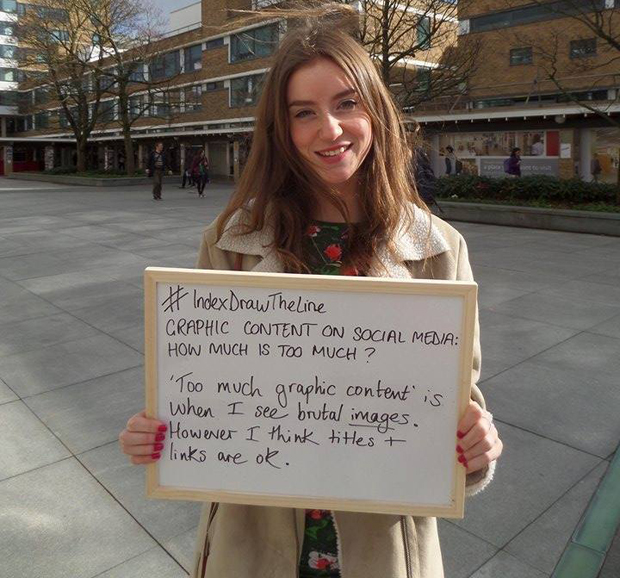

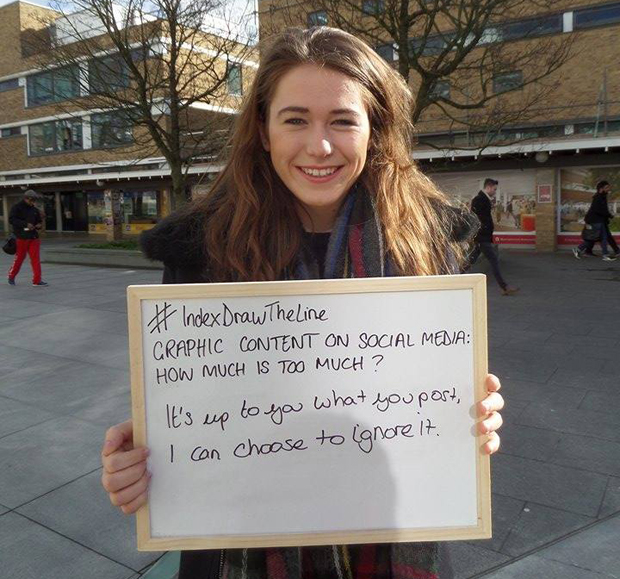

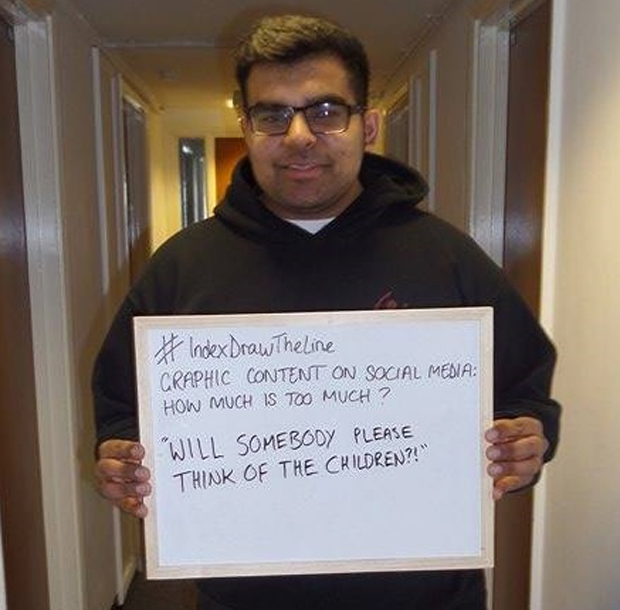

This month, we’ve been asking the question “Graphic content on social media: How much is too much?”

While graphic content shown in mainstream media usually comes with a content warning, as well as being subject to the editing processes of news outlets, social media largely operates according to rules of its own. Whether or not we choose to post graphic content is often left to our discretion – so where should we draw the line?

As well as the response on our social media feed, we also got the views of some students at Lancaster University in England, in the form of photographs which you can see below.

In reaction to this month’s question, concern was expressed about the age of social media users who might have access to graphic content, which is a growing issue given the number of children who now have social media accounts.

The issue of the intention behind the content posted was also raised – what are these users trying to achieve? Is content shared to raise social consciousness and spread awareness? Or is the intention to promote discrimination and fear? One example from our Twitter feed, which is along these lines, referred to the photographs of the brutal murder of blogger Avijit Roy, along with the question of whether these images were posted to provoke Islamophobia.

Others gave responses centering on the issue of personal choice; both what they choose to post and what they choose to see. In other words, they were most comfortable with the sharing of graphic content when it still allowed viewers an element of choice, and favoured posting links and titles rather than images and videos themselves which viewers could then choose to investigate further, or disregard.

Perhaps then the balance can be found where people have both the freedom to share graphic content, and also the freedom to not have it forced upon them.

This article was posted on March 24 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

Back in November 2015, York co-founded Online Censorship, a user-generated platform to document content takedowns on six social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Flickr, Google+ and YouTube), to address how these sites moderate user-generated content and how free expression is affected online.

Back in November 2015, York co-founded Online Censorship, a user-generated platform to document content takedowns on six social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Flickr, Google+ and YouTube), to address how these sites moderate user-generated content and how free expression is affected online.