29 Jan 2015 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, United Kingdom

Sometimes, when I’m bored, or a bit down and feel the need to believe there are people in the world who are worse to me (worse, not worse off), I turn to TripAdvisor.

I’m sure there are perfectly reasonable people on TripAdvisor. Perfectly normal people, who may have enjoyed a dinner somewhere, or made friends with the barman at their holiday hotel, and thought “I must tell the world! These hardworking service industry people deserve my support.” I’m sure there’s lots of that going on on TripAdvisor (other review sites are available).

These happy people do not concern me. No, these are not the reviews I want to read. I seek out the one and two stars which are often written by the worst people in the world.

Petty, greedy, stingy, paranoid and usually convinced of their own way with imagery. Imagine eating out with these people.

The waitress approaches, smiling (as they often do):

“Would you like to see the wine list?”

“Yes please.” (List is delivered. Exit waitress).

“What do you think she meant by that?”

“What?”

“Asking if we wanted the wine list like that.”

“Like what?”

“Didn’t you hear her?”

“Yes. She said ‘Would you like to see the wine list?’ They often do.”

“But it was the waaaayyyy she said it.”

“Uh.” (Scans room for exits, sees only cheery floor staff).

On goes the evening. Everything is noted. The wine is too cold, the food too hot. Side orders are too expensive, there’s a draft only your dining partner can perceive. The service is too slow/fast. Somehow, in spite of it being a busy night, the waitress has been giving your companion a Paddington hard stare all night.

No, you certainly will not be having dessert, not at these prices.

The bill arrives, and is divided down to the last pea (“You got more ice in your tap water than I did”).

You depart, he on his bus, you on yours. On his way home, he cancels his debit card because he’s sure the restaurant people will have cloned it. You reach home and climb into bed, despondent. His fun though, has just begun.

Pouring himself a decent measure of the large whisky he hides when visitors are around, he settles on the sofa and logs into TripAdvisor (other review sites etc).

“Our trouble started,” he types. “When my friend called to book the table.” (You are now implicated).

“Having read my neighbour Giles Coren’s fine review in the Times of London, I was expecting high things of Brasserie Sarkozy. Methinks Coren the Younger’s judgement may have been clouded by one too many stiffeners over lunch, perhaps with his delightful sister, Victoria (with whom I would be only too happy to ‘Only Connect’!)…”

Why are you friends with this person again? On he goes. The broccoli was insufficiently purple. The steak (always steak) was “inferior” to the Specially Selected 30 Day Matured Aberdeen Angus Sirloin you get in Aldi for just £5.99. The staff were too casual, the room too stuffy, the building in the wrong neighbourhood… And the prices? Is this Monte Carlo?

And he wouldn’t have minded that much if it wasn’t for the rat he almost certainly saw in the gents.

Your friend clicks “one star” closes down his computer, and heads for bed, to dream of the panic when the restaurant’s owners (shysters and rip-off merchants every last one of them) discover his latest mighty internet onslaught.

One wonders if your friend (let’s call him gourmand_Gareth, as that’s what he calls himself), drunk on power, has considered the consequences. Particularly the consequences of the claim about the rat in the toilets, which, while he didn’t quite intentionally make up, is a bit of a misreport. Specifically, he’s moved the rat’s location from “in his imagination” to “standing on the cistern, singing Blur’s classic Britpop ballad To The End”. It didn’t happen. It is wrong to publish a review saying it did. It’s quite probably libellous. In fact, the chef is on the phone to his lawyer right now.

I don’t like your friend (I suspect you don’t either, but you’ve known him since school when… Actually you didn’t like him then either, did you?), but I don’t want him to end up in trouble.

But this is what could happen. While there’s only ever been one successful libel case against a restaurant reviewer in the United Kingdom (Goodfellas v Irish News, 2007, overturned on appeal, fact fans), there has been a rise in libel cases involving social media and the web. According to the Independent, there was a 300 per cent increase between 2012-13 and 2013-14 alone.

In spite of the work done by Index on Censorship and others in improving England’s libel laws, being sued — even being threatened with libel action — is still a deeply unpleasant experience, and quite possibly an expensive one too. Meanwhile, continued threats to the concept of the “mere platform” (that is to say, a site such as TripAdvisor, which allows people to post content without pre-moderation, should not be held legally liable) face threats from the actions of Max Mosley and others who are determined that the web be a more tightly controlled space.

Pre-moderation (editing, in effect) is anathema to how we use the web every day. Try to imagine having to send every tweet to some poor bugger in an office in Dublin who then has to decide whether it gets past every single restriction on speech in the European Union before he publishes it to your page. Not going to happen, no matter how many European courts believe it should.

But on the other side of the coin, people like your friend Gareth should at the very least be aware of what the laws are, and what risks they run. The past few years have seen countless cases of people facing civil and criminal sanction for tweets where they clearly had no idea what the law was (*innocent face*). This is not a plea for more laws, or even more self-censorship. But one does wonder if basic education in what the potential pitfalls of online interaction are, is necessary. Index and its partners are bringing out guides for artists to free speech and the law, but what about the rest of us? It’s too late for poor, silly Gareth.

This article was posted on January 29 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

23 Jan 2015 | News

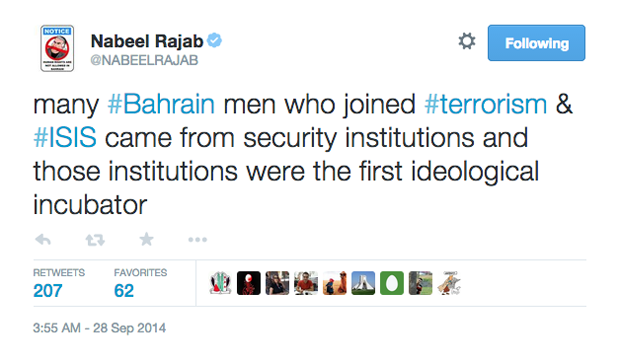

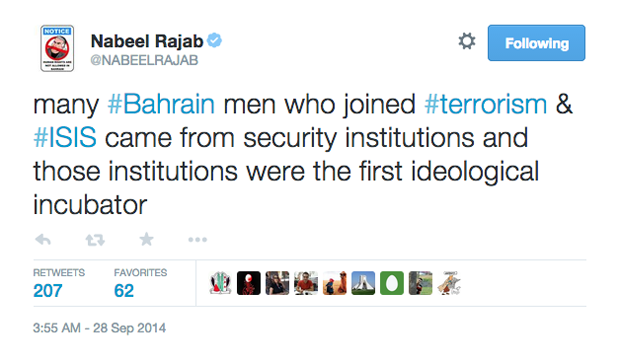

Bahrain

This week, prominent Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was handed down a six month suspended sentence over a tweet in which both the country’s ministry of interior and ministry of defence allege that he “denigrated government institutions”. Rajab was only released last May after two years in prison, over charges that included sending offensive tweets. His experience is not unique in Bahrain. In May 2013, five men were arrested for “insulting the king” via Twitter.

Turkey

A former Miss Turkey was recently arrested for sharing a satirical poem criticising the country’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on her Instagram account. She is set to go on trial later this year. Turkey has a chequered relationship with social media, temporarily banning both Twitter and YouTube in the wake of the Gezi Park protests, in large part organised and reported through social media. In 2013, authorities arrested 25 individuals for spreading “untrue information” on social media.

Saudi Arabia

(Photo: Gulf Centre for Human Rights)

In late 2014, women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets. The charges against her include “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”, according to the Gulf Centre for Human Rights.

France

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)

(Photo: Réseau Voltaire [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

Following the series of terrorist attacks in Paris in early January, at least 54 people have been detained by police for “defending or glorifying terrorism”. A number of the cases, including against comedian Dieudonne M’bala M’bala, are believe to be connected to social media comments.

Britain

A 22 year old man was arrested in for “malicious communication” following Facebook messages made in response to the murder of soldier Lee Rigby, and another user was arrested after taunting Olympic diver Tom Daly about his dead father. More recently, police arrested a 19-year-old man over an “offensive” tweet about a bin lorry crash in Glasgow that killed six people. TV personality Katie Hopkins, known for her controversial tweets, was also reported to Scottish police following some tasteless tweets about about Scots. The incident prompted Scottish police the to post their now infamous tweet declaring they would continue to “monitor comments on social media“.

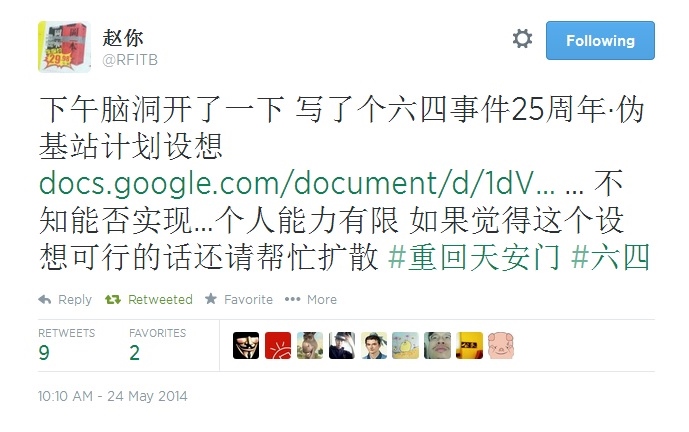

China

Online activist Cheng Jianping was arrested on her wedding day in 2010 for “disturbing social order” by retweeting a joke by her fiance. She was sentenced to one year of “re-education through labour”. Twitter is officially banned in China, and microblogging site Weibo is a popular alternative. In 2013, four Weibo users were arrested for spreading rumours about a deceased soldier labelled a hero and used in propaganda posters. The four were said to have “incited dissatisfaction with the government”, according to the BBC.

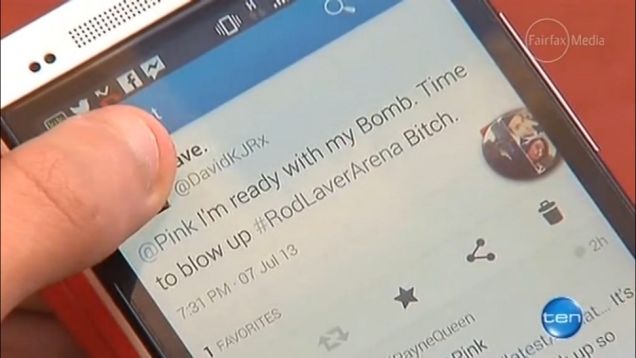

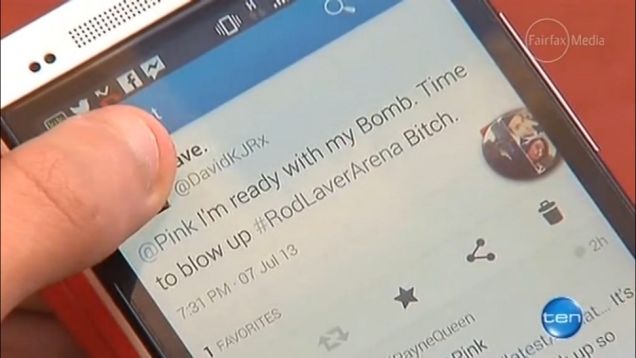

Australia

A teen was arrested prior to attending a Pink concert in Melbourne for tweeting: “I’m ready with my Bomb. Time to blow up #RodLaverArena. Bitch.” The tweet referenced lyrics from the American popstar’s song Timebomb.

India

An Indian medical student was arrested in 2012 over a Facebook post questioning why her city of Mumbai should come to a standstill to mark the death of a prominent politician. Her friend was arrested for liking the post. Both were charged with engaging in speech that was offensive and hateful.

United States

Back in 2009, a New York man was arrested, had his home searched and was placed under £19,000 bail for tweeting police movements to help G20 protesters in Pittsburgh avoid the officers. According to Global Voices, it is unclear whether his actions were actually illegal at the time.

Guatemala

A man was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing all their money from banks.

This article was posted on 23 January, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Nov 2014 | Americas, Digital Freedom, Europe and Central Asia, Ireland, News, United Kingdom, United States

How did people organise protests before the internet? How did riots happen? How did terrorists carry out attacks? All these things definitely happened. I remember them distinctly. In the days before the world wide web, all sorts of things occurred without anyone “taking to social media” or “using sophisticated communications technology” (phones).

But current discussions are premised on the idea that the web in itself has created civil disorder and even terrorism.

In Ireland, as protests have got to the point where government ministers can barely leave the house without being confronted by citizens unhappy with proposed household water metering, commentator Chris Johns suggested that “Social media has brought more illness to Ireland than Ebola has. Anarchists, extremists and all-round loonies can find a voice and organisational structure – if only for a decent riot – amidst a political fragmentation that rewards those who shout the loudest.”

Considering there have been no recorded incidents of Ebola in Ireland, the first part of this assertion could be technically true; or we could say that social media has brought the same amount of illness to Ireland — none. As for the anarchists and loonies, well, they have always been with us, and had some success in organising before Facebook came along.

Across the Atlantic, St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Robert McCulloch said that “nonstop rumours on social media” had significantly hampered the investigation into the killing of Michael Brown, and contributed to his decision not to prosecute. This in the land of the First Amendment, where the justice system long ago learned to deal with hearsay.

Back over the ocean again, the UK’s Intelligence and Security Committee report into the murder of Drummer Lee Rigby by Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale pointed to a Facebook message sent by Adebowale, in which he expressed a desire to kill a soldier. In spite of several failures by the intelligence services, who were long aware of Adebowale’s tendencies, Facebook faced criticism for not “flagging up” the message to the security forces. Social media to blame once again.

Why do we do this? Why must every single occurrence now have a social media angle?

Partly because everything many of us do now does have an internet angle. The web is simply part of human interaction for millions.

But for some it seems foreign. My generation is the last that will remember life before the internet.

For all that, it is still shockingly new. I’m not just saying that to make myself feel younger. Some people my age and older (“digital immigrants”, apparently, which makes me a double immigrant) have adapted reasonably well to our new environment. Some really haven’t. I have watched a QC attempt to explain the difference between a reply and a direct message on Twitter. It was as you’d expect, equal parts cute and infuriating, but it did also make one think how insanely fast we have adapted to certain technologies, and how some people are left behind.

When was the last time they changed Facebook? I honestly couldn’t say. But remember when complaining about changes to Facebook was a thing? We used to object; now we install our own mental updates and carry on, using new features and forgetting what went before. I have literally no idea what Facebook looked like when I joined it. Or Twitter for that matter.

And I, remember, am an immigrant, not a native. There are still a lot of people who don’t want to emigrate to the web, because they think it’s full of conspiracy theories and pornography. And there are some who occasionally “log on” to the internet, and then “log off” again, like an overnight work trip to Leicester.

So when something happens that involves an email, a tweet, a Facebook update or whatever, for some that is still of interest in itself.

Will this ever end? Hopefully. As time goes on, the distinction between the internet and THE INTERNET will become clearer. THE INTERNET is a culture; the place where the likes of Doge and Grumpycat come from, and all their predecessors (I still have a soft spot for Mahir “I Kiss You” Çağrı. Look it up, youngsters). The internet is simply a communications tool, like millions upon millions of tin cans joined with taut string. When we can get this a little clearer in our heads, then finding a web angle for every occasion will feel a bit silly, like blaming Bic for poison pen letters.

That is not to say that we should take the web for granted, or become blase about its use and abuse. But we must treat it as simply a part of the environment. Essentially, we have to stop thinking about things happening “on the internet”. There is no “internet freedom” — there is just freedom. There is no “internet privacy” — there is privacy. There are no “internet bullies” — there are bullies.

Put simply, we need to ban the word “internet”.

This article was published on 27 November 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Aug 2014 | Asia and Pacific, India, News

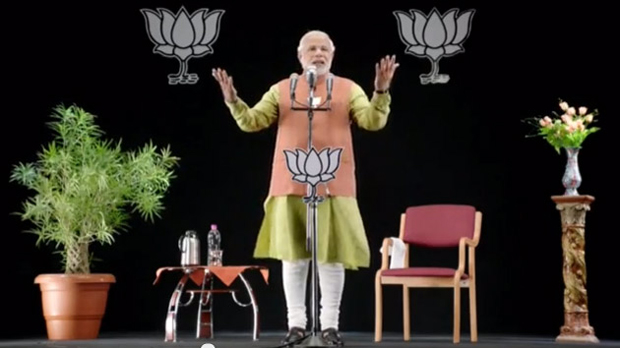

While campaigning to become prime minister, Narendra Modi addressed voters through 3D technology on several occasions (Photo: Narendramodiofficial/Flickr/Creative Commons)

Indians don’t usually take much notice of the prime minister’ speech on independence day in the middle of August. This year was different. This year there was so much discussion on social media that it became a trending topic.

In contrast to the way other prime ministers have handled this moment, new Prime Minister Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), wowed a large section of Indian society not just with what he said, but the way he said it. People are gushing over the fact that he spoke without notes, and did not use the usual bulletproof glass. Others are impressed with the content; he touched upon topics as diverse as rape, sanitation, manufacturing, and nation building, using easily accessible language. Modi is also using social media to get his views across direct to the public, and bypassing the mainstream media.

This straight-talking style only adds to Modi’s brand, but he is also attracting criticism from the mainstream media for not being willing to answer hard questions. His chosen methods of communicating with the public have one common thread: he prefers to address the public directly, plainly, without going through the mainstream media or any reliance on further explanation by them. His social media accounts on Facebook and Twitter have completely changed the way information comes out of the prime minister’s office (PMO). Modi’s tweets, both from his personal and his prime ministerial account, keep citizens updated on his various trips (“PM will travel to Jharkhand tomorrow. Here are the details of his visit”). He also updates on his musings (“I am deeply saddened to know about Yogacharya BKS Iyengar’s demise & offer my condolences to his followers all over the world”) and highlights from speeches made across the country (“when the road network increases the avenues of development increase too”), as well as photographs and videos. Citizens are getting a front row seat at his speeches and thoughts. But not everybody is happy about this — especially not the private mainstream media.

Unlike the previous government, Modi is yet to appoint a press advisor. That person, normally chosen from senior journalists in New Delhi, advises the prime minister on media policy. There isn’t a point person from the PMO for the mainstream media — or the MSM, as it is called — to discuss stories and scoops. He only takes journalists from the public broadcasting arms — radio and TV — on his foreign trips, in contrast to his predecessor, who brought along more than 30 journalists from the public and private channels. In fact, Modi has reportedly instructed his MPs to refrain from speaking to journalists. Indian mainstream media is filled with complaints that Modi is denying journalists the opportunity to engage with complex subjects like governance beyond official statements and limited briefings. Meanwhile, some other publications have scoffed that the mainstream media is only complaining because it will be forced to analyse the news and work towards coherent reporting instead of relying of well honed cosy relationships with people in power.

This apparent rift between the PMO and the private mainstream media has to be viewed through a variety of prisms for it to make any sense. The first is the very volatile relationship between Modi and the MSM which harks back to his time as chief minister of Gujarat, when a brutal communal riot took place. The second is the state of the mainstream media itself, continuously called out for unethical practices by the likes of the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India.

The relationship between Modi and the mainstream media is complex. No court has indicted Modi for any criminal culpability in the Gujarat riots of 2002, but many in the media have held him morally responsibly for the mass killings that carried on over three days, and let their feelings colour reports on him. But right before Modi’s historic sweep of the Indian general elections, this section of the press seemed to have begrudgingly warmed to the man they had long vilified.

One of India’s most respected journals, Economic and Political Weekly, published the article Mainstreaming Modi, deconstructing this new wave of coverage. It argued that the reasons for this change “range from how even the United Kingdom and the European Union have ‘normalised’ relations with him [Modi], that he has been elected thrice in a row to the chief ministership of Gujarat, which surely speaks of his abilities as an ‘efficient’ and ‘able’ administrator, that Gujarat has become corporate India’s favourite investment destination, and most importantly, that he is the guy who can take ‘decisions’ and not keep the nation waiting for action.”

During this year’s election campaign, Modi’s use of the media was innovative. Stump speeches were tailor made for the towns he was campaigning in. Modi’s 3D holograms, deployed in small towns while gave a speech elsewhere, were a spectacle not seen before in India. Though Modi had been speaking to Hindi and other Indian language media, he delayed giving interviews to the English language “elite” media, watched by a small but influential section of the population. He finally consented to doing a one-on-one interview with Arnab Goswami of Times Now, known as one of India’s loudest and most aggressive anchors. People readied themselves for the ultimate combative hour on television, but Modi’s no-nonsense answers, it seemed, won over both the anchor and the audience — especially as they were in sharp contrast to the vague statements put across by Modi’s challenger, Indian National Congress Party candidate Rahul Gandhi.

After the election win, India’s mainstream media has been forced to reassess what it wants from the prime minister. Is it information or is it access? The mainstream media undoubtedly has had a very complicated and close history with the political class. A Congress-led government has been ruling New Delhi for a decade, building up close relationships with senior editors and journalists. Some of these relationships were exposed through leaked conversations between members of the press and corporate lobbyists in a scandal now known as the Radia Tapes. They revealed, among other things, how journalists used their connections to politicians to pass on messages from lobbyists.

In fact, the indictment of improper behaviour by the media is a fairly regular occurrence in India. Just this month, the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India released their latest report, which recommends that corporate and political influence over the media can be limited by restricting their direct ownership in the sector. For this reason, the credibility and true affiliation of the media is always under the scanner.

But Modi and his team also need to respond to questions about why they will not deal with some parts of the media. How do they view the role of a combative media? Is only the public broadcaster, which reports the story as the government wants, to be allowed access? Are critical questions being avoided?

Perhaps, the last word can go to Scroll.in, one of India’s newest online magazines: “[T]he rat race for the ego scoop undermines the most important scoop, the thought scoop. We often don’t look at the big picture, don’t take the long view, don’t see the obvious, forget the past, don’t study the boring reports, substitute access journalism for ground reporting, believe the official word. Narendra Modi might just be doing us a favour by keeping us away.”

This article was posted on August 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)