16 Dec 2013 | Africa, News and features, Politics and Society, South Africa

(Photo illustration: Shutterstock)

Even as South Africans commemorate their global icon Nelson Mandela’s life-long struggle for human rights, shock waves have hit the media after the sudden dismissal of well-respected Cape Times editor Alide Dasnois. This follows a front-page lead article on 6 December on a report on corruption in which the new owners of the paper are implicated.

The Cape Times is part of the Independent Media stable which includes 18 daily and weekend titles. Sekunjalo Holdings, a company perceived to have close ties with the ruling African National Congress, bought it in the middle of 2013 from the Irish-based Independent News and Media (INM).

The corruption report, by the country’s statutory Office of the Public Protector, found that the fisheries department’s award of an R800 million (GBP £47 million) tender for the provision of marine patrol vehicles to a Sekunjalo subsidiary was biased, improper and amounted to maladministration.

Social media have been abuzz with criticism against the removal of Sorbonne-educated Dasnois. She is known as an ink-in-the-veins journalist who is dedicated to fair and accurate news coverage with integrity. In response to the outcry, Sekunjalo executive chairperson Dr Iqbal Survé claimed in a public statement on 9 December that Dasnois was “not fired” but offered other positions. He also suggested that the decision to “move” Dasnois was in response to the “wholly unsatisfactory sales performance of that title over the last few years”. In regard to this claim, it is worth noting that declining circulation besets the whole of South Africa’s newspaper industry and is not limited to the Cape Times.

Survé added that “a concerted public campaign of lies and distortions” is responsible for “some stat(ing)… as fact – without a shred of proof offered in evidence – that Alide Dasnois’s replacement was the result of the story published as the lead in the paper last Friday (6 December), regarding adverse findings by the Public Protector against a government minister in the award of a tender to one of the companies in the Sekunjalo Group… I and Independent deny this version of events categorically.”

However, contradicting this claim, Sekunjalo’s lawyers had sent a letter dated 7 Dec to the Cape Times demanding a prominently published apology from Dasnois and reporter Melanie Gosling who wrote the article on the Public Protector findings. Sekunjalo threatened to sue them for damages. His lawyers wrote:

“Our instructions are that you have reported extensively over the past two years on the allegations by the disappointed bidder SMIT Amandla [Marine] and Mr Pieter van Dalen of the Democratic Alliance regarding Sekunjalo’s role in the award of the tender for management of the research and patrol vessels of the department of agriculture, forestry and fisheries [DAFF].

Our client has instructed us to record the following:

1. It has been alleged that Sekunjalo Investments Ltd is guilty of corruption; that it had misled and/or defrauded DAFF; that it lacked the experience and expertise to undertake the management of the research and patrol vessels of DAFF; etc.

2. These allegations have been thoroughly debunked.

3. The report by the public protector clears Sekunjalo of all wrongdoing.

4. It would have been appropriate, after months and months of sustained attacks on the integrity of Sekunjalo, if the Cape Times had published on its front page the more accurate articles which were buried on page 18 of (Cape Times) Business Report of December 6 2013, that Sekunjalo had been vindicated, and that the company demanded an apology.”

The lead-up to this moment can be traced further back than the offensive front-page article. On 5 December, in anticipation of the release of the Public Protector’s findings, an article by Survé occupied the main space on the op-ed page in the Cape Times. He wrote about a “dirty tricks campaign” against himself and Sekunjalo – specifically an article published in the Sunday Times on 1 December containing leaked findings of the then still-to-be-launched Public Protector report on Sekunjalo and the fisheries deal. Survé accused the Sunday Times, owned by the Times Media Group, of collaborating with the opposition political party the Democratic Alliance.

It was not the first time that Sekunjalo’s newly acquired newspapers have been used as platform to defend the company against adverse reporting from competitors. The Mail and Guardian in August published Survé’s response to questions about the ownership structure of Independent Media after the acquisition. In an apparent retaliation, a front page article in the newspapers’ daily insert Business Report accused the Mail and Guardian of sour grapes after Survé rejected its offer to purchase some of the Independent Media titles. It mentioned that Survé had accused the Mail and Guardian of being funded by the CIA.

The Cape Times letters page on 6 December featured three letters from readers expressing concern about Survé’s abuse of his position to print an attack on the Sunday Times for exposing irregularities that his company is implicated in. On the same day the editorial acknowledged concerns by readers about whether the publication of Survé’s article heralds a change in the newspaper’s policy of editorial independence. It assured readers that the Cape Times will continue to publish all views, including from those criticised by Survé.

It ended with the assurance that “we believe readers have nothing to fear”, and quoted the concluding paragraph in Survé’s article: the Independent Newspapers should “remain what it has always been, a place where all worldviews, ideas and political schools are welcome”. Dasnois was fired on the same day.

Sekunjalo’s demanded apology in the 9 December edition did not transpire, suggesting that Dasnois had refused to apologise, leading to her removal. She has meanwhile indicated that she is investigating her legal options, while Cape Times staff and the SA National Editors Forum have demanded answers. A petition is circulating for her reinstatement. The Cape Times omitted any mention of Dasnois’s dismissal on 9 December – only that Sekunjalo would lay a complaint with the press ombud with regards the lead article. On 10 December the paper published Sekunjalo’s reason for removing Dasnois as “falling circulation”, with no response from her.

On 12 December presented the “real reason” why Dasnois was removed. In a public letter to staff he claimed she had refused to run with the death of Mandela as the lead in the paper on Dec 6, even though this was agreed at a meeting between editors and management (which, if it is the case, would be tantamount to interference in editorial decisions). However, his claim that Dasnois as experienced journalist would miss the news story of the year makes little sense. Indeed, the Cape Times featured a four-page wraparound with Mandela on the front cover on 6 December. The paper’s op-ed editor, Tony Weaver, devoted his weekly column on 13 December to the process of producing the Mandela edition of the paper on Dec 6, refuting Survé’s allegations.

The new owners have moved swiftly to replace Dasnois, with Gasant Abarder taking her place. He has yet again assured readers of the independence of the paper.

5 Dec 2013 | News and features, South Africa

Oliver Tambo (Image: Rob C. Croes / Anefo / Wikimedia Commons)

In May 1986 Oliver Tambo, then president of the African National Congress, was interviewed by former Index on Censorship magazine editor Andrew Graham-Yooll in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The following are extracts from the conversation.

—

Are you planning for a time after apartheid?

Oliver Tambo: That should not pose a problem. We do not find it necessary as yet to have people assigned to specific roles in the new South Africa. I don’t think we should have any problem deciding who should do what. For the moment the priority is to concentrate on ending the system. We say we want a government that derives its mandate from the people of South Africa as a whole, a majority government. If we had to pick a cabinet we would do that without any difficulty.

We have never ever doubted that apartheid will crumble some day. Now, we are able to say some day soon. We have never had any doubt about this. We know that we will be in Pretoria soon – if we choose Pretoria to be the seat of government. But it is so notorious as the seat of apartheid that the people who will be in power (not necessarily Oliver Tambo) might want to go elsewhere. But there will be a government of the people in South Africa and we will all get there some day soon. We have never doubted this. Some day soon, is how we look at it. ‘Soon’ can be stretched. We labour under no illusions that apartheid will not fall without heavy sacrifices possibly even after a protracted and vicious confrontation. We are prepared for that but at the end of the day we know apartheid must end.

Is there a real possibility of a peaceful transition to majority government?

One hopes it will not be too violent, but we must be prepared for the reality.

Pressures have got to be external and serious up to the point where we are able to say apartheid has been destroyed and a new South Africa is emerging. But if we should withhold pressure, even withdraw it, then apartheid continues. It is only since 1985 that international pressure has begun to measure up to the demands of the situation, encouraged significantly by the rising pressures from within the country. These two have resulted in a new thinking on the part of those who are administering the apartheid system.

You have compared 19th century colonialism and racism and 20th century imperialism and apartheid.

The point was that at the heart of apartheid was racism. Apartheid is the strongest concentration of racist concepts put into action. But that did not start with apartheid, it was there before. It found expression in colonial practice. In fact, one can say that in South Africa racism started with the first settlers. It was with the Dutch before 1805. Well. I should not say the first because it was a later development.

When Dutch settlers got there they found indigenous people. There was no racism at that point, they were just different people. Subsequently, laws were introduced which enforced separation. Then the British came. Their most racist act was the constitution, which incorporates racist clauses. From there racism developed roots. Racists were encouraged and in the end they had a racist government in power. But they were built on the constitution adopted by a British government and so you have this monster of apartheid.

But the point is that what we see today has been there before. Perhaps the true process of reversal can only start in South Africa where it has reached its worst. If you can succeed in uprooting this thing in South Africa, I think that the fate will be to eliminate racist practices everywhere. Especially if we do succeed, as we are hoping, in creating a new relationship between people, learning from the horrors of the apartheid system. Just as we hoped that people who worked against Nazism would not want to entertain anything like it again. Those who have experienced the worst excesses of racism should want to get away from that totally. They should have a completely non-racial system of a kind which should be attractive internationally.

If only people could live together, innocent of colour, skin colour, of racial difference… South Africa therefore may well be the starting point of this end to racism which has been with us in the world for centuries.

How do you see the predicament of South Africa’s neighbours?

It is a predicament. They have been put in that situation by history. They found themselves in that position before independence. There was nothing wrong with that. South Africa was the heart of their economies and they were linked to South Africa. If you did not have the apartheid system, or if the transition to democratic rule in southern Africa had taken place at the same time as it did in these other territories we would have had no problem at all. But they became politically independent first and are therefore quite naturally opposed to the colonial system in South Africa. They were themselves involved in colonial struggles. They have achieved their objective of winning political power at least, we have not. So they support us.

But there is more to it than that. The apartheid system is inhuman to its victims and makes fools of them. So the neighbouring states want to see it ended. They do what they can, they recognise the reality of the situation. They do care, they cannot fight. They can only defend themselves if they are attacked. But even then it would not take too long before they were overwhelmed. They cannot impose sanctions because of their tremendous dependence on South Africa. But they do the next best thing, that is to organise themselves into a collective, SADCC, which seeks to reduce that dependence. That is the next best thing. They are neighbours, so they are liable to be harassed and destabilised. The South Africans can impose sanctions against them, they impose sanctions against Mozambique, they have imposed sanctions against Lesotho and they can invade and raid Botswana.

When we call for sanctions we have to make an exception, it is understood. We make an exception with regard to the countries that border South Africa, because their economies are dependent on trade with South Africa. So they are not called upon to impose these sanctions. They know that if sanctions were imposed they would be the worst affected, and they say that is the sacrifice they have to make. Of course, we all hope that the opponents of apartheid who enforce sanctions would want to minimise the adverse effect on these countries. In other words, we want them to be given assistance to enable them to survive the effect of sanctions.

This article was originally published in Index on Censorship magazine in 1986.

Click here to subscribe to Index on Censorship magazine, or download the app here

5 Dec 2013 | News and features, South Africa

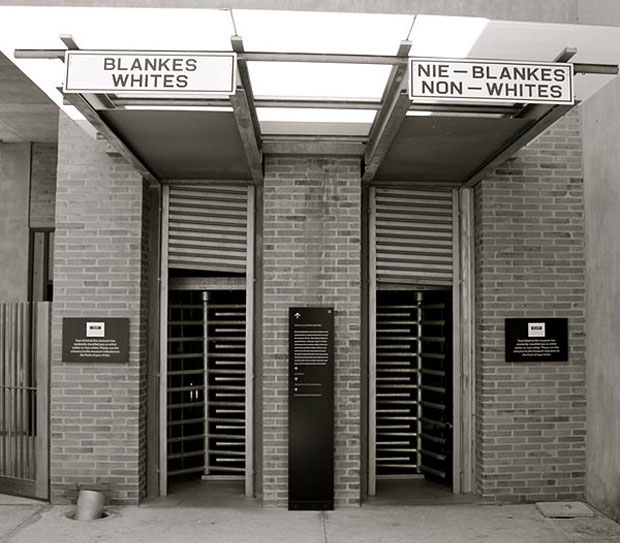

(Image: Annette Kurylo/Wikimedia Commons)

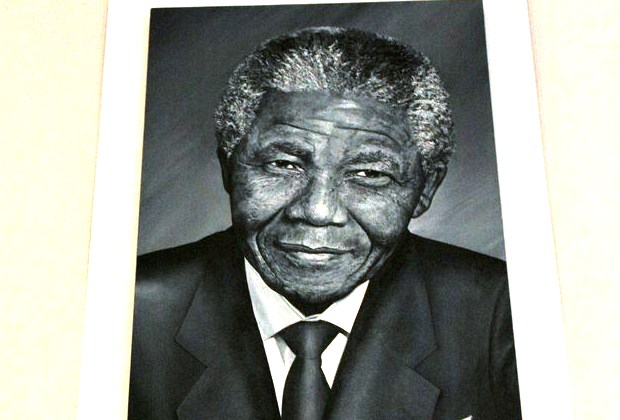

If Nelson Mandela’s legacy is summed up by one thing, it will be in symbolic moments, like the times when those “whites only” signs were torn down, no longer shouting that South Africa was a society where only its white people had opportunity, and aspiration, and when a reborn nation began its journey on a previously uncharted road to freedom.

At Index on Censorship we have collected significant articles from our archive that trace the history of the apartheid struggle, and some of the great writers who have commented, argued and analysed it for our magazine, including Nadine Gordimer and Albie Sachs.

Please browse them and remember the immense changes that Nelson Mandela helped make happen.

This is the moment to remember massive changes in South African life that are Nelson Mandela’s legacy says Rachael Jolley

This is the moment to remember massive changes in South African life that are Nelson Mandela’s legacy says Rachael Jolley