South Korea: Film raises questions about Cheonan sinking

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.

A recently released film in South Korea set out to spark a discussion on free speech in the country, and amid opposition and cancelled viewings, it has done just that.

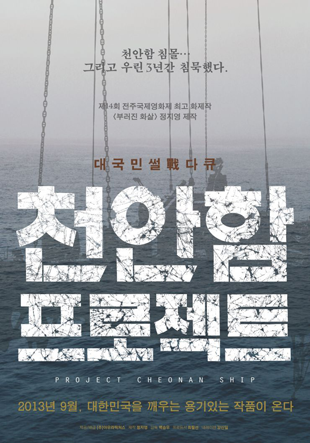

Project Cheonan Ship is a film on the aftermath of the 2010 sinking of the Cheonan warship, a South Korean navy submersible that went down in waters near North Korea. South Korea concluded that a North Korean torpedo was the cause of the sinking, though North Korea denied any involvement. The film features experts in a range of fields offering possible alternative causes of the ship’s sinking.

In August, members of the South Korean navy and relatives of a few of the 46 sailors who died in the sinking sought a court injunction to prevent the film’s release. “There is freedom of expression, but no freedom of distortion…If the movie is released, it could defame the reputations of the 46 fallen soldiers and their bereaved families”, the group’s lawyer said in a statement.

The injunction was denied in court and the film opened according to schedule on Sept. 5 at 30 theaters across South Korea, mostly in independent film houses but in a few major theaters as well. It did well on its opening weekend, ranked first among independent films and eleventh overall at the box office.

After two days, the film was pulled by Megabox, a major theater chain. This is believed to be the first time in Korean history that a film has been pulled in this way. Megabox said that they had received warning from conservative civic groups who planned to picket the theaters showing the film. The theater company said they didn’t want to put viewers’ safety at risk, and therefore stopped showing the film to avoid trouble.

A big part of the reason why the issue of the Cheonan sinking is still prickly is that there was a long debate over the cause of the sinking and though the evidence strongly points to North Korea, there still isn’t a uniform consensus on what happened. An international investigation commissioned by the South Korean government eventually concluded that indeed, a North Korean torpedo had sunk the Cheonan. Skeptics continued to argue that the ship could have come in contact with a mine leftover from the Korean War.

The debate over the sinking has been split along the lines of South Korea’s political divide: conservatives who support the South’s military alliance with the US and are bitterly opposed to North Korea, and those on the left who don’t approve of the large US military presence in South Korea and see it as the main obstacle to peaceful reunification with North Korea.

People in South Korea who voice either explicit or implied support or sympathy for North Korea are often shouted down. There is even a law banning expressions ofsupport for the North: Article 7 of the National Security Law (NSL) stipulates up to seven years in prison for anyone who “praises, incites or propagates the activities of an anti-government organization”. Under the law, North Korea counts as just such an anti-government organization.

While supporters say the NSL is necessary to protect a fragile peace against the North Korean threat, critics say it is a vaguely worded prohibition that is really meant to stifle dissent within the country.

The makers of Project Cheonan Ship intended not to take a position on the cause of the Cheonan sinking, but to start a conversation about the importance of unimpeded expression of differing views. “Our primary motivation was not telling a story about the Cheonan sinking case itself, but about the intolerant attitude seen in our society after the incident,” Director Baek Seung-woo said in an interview on Sept. 13.

Baek said he and the other filmmakers wanted to reiterate the importance of free speech in South Korea. “We made this movie because we believe most people in our society have an understanding of what free speech means, but don’t yet fully appreciate its value,” he said.

Even after making the film, they still don’t attempt to make definite claims on how and why the Cheonan went down. Baek explained, “While making the movie, I realized how extremely difficult the case was. I am not expert on marine science or military equipment or explosives. I’m not scientist either. I don’t know what the cause is, but I think the real experts in our society need a more open climate of free speech to really figure out what happened.”