Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

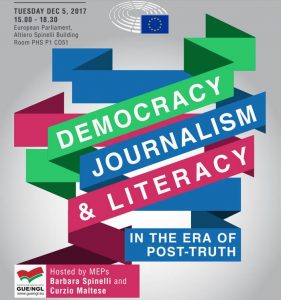

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Veteran Belgian journalist and author of Terrorism and the Media, Jean-Paul Marthoz delivered the following remarks on 5 December 2017 at a round-table debate in the European Parliament hosted by MEPs Barbara Spinelli and Curzio Maltes:

Democracy, journalism and literacy in the era of post-truth

Everything has been said on fake news. Since the word ‘post-truth’ was chosen as the word of the year in 2016 by the Oxford dictionary there is not one day without an evocation of the ‘new kingdom of lies’.

Fake news however, as it is currently understood, is not any kind of lie. It is a deliberately mendacious or misleading information, specifically designed to have a disrupting impact (on society, geopolitics, etc.) and to become viral in the media and on social networks.

The word has taken on an eminently political connotation with Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign. The unexpected candidate of the Republican Party turned it into a brand, not only by filling his speeches and tweets with approximative or even false facts but also by accusing quality media of being the ones producing fake news.

The word has taken on a strategic dimension with accusations of Russia’s intervention in the US electoral campaign. In the current remodeling of the world, fake news is part of strategies of influence and belongs to the arsenal of asymmetrical warfare.

Migration has been none of the privileged targets of these rogue concepts of information. During his campaign Donald Trump lambasted Mexican ‘bad hombres’. The Brexit campaign was polluted from end to end by made-up stories on Syrian refugees and Polish plumbers.

Migrations have always lead to fabrications and exaggerations. Before the word fake news even appeared, many media, UK tabloids in particular, exploited the vein, with extravagant headlines on migrants. It was a banal case of media sensationalism. Today however the theme of migrations is used strategically in order to sow confusion within European countries and to support populist movements who, nearly everywhere in Europe, question the foundations and values inscribed in EU treaties. It is one of the most efficient levers of populism and far right extremism.

Such strategy benefits from an exceptional soundboard in social networks. These are not only used by millions of citizens who intervene, sometimes wisely, sometimes through their hat, in information flows and public debates, but also by organized, and at times even robotised, groups who pursue a deliberate policy of occupation and agitation on the social networks.

Some have made disinformation a business, like these Macedonian kids who had their moment of fun when they informed about the Pope’s endorsement of Donald Trump, leading to millions of clicks and thousands of dollars of ad money. But this is an epiphenomenon, an anecdote, when compared with the political strategies that have been put in place.

Fake news is a direct attack against the democratic ethos. It aims at polluting the agora, leading, in Matthew D’Ancona’s words in his book Post Truth (Ebury Press, 2017, p. 2) to ‘the infectious spread of pernicious relativism disguised as legitimate skepticism’.

The labelling of prestigious media as ‘fake news’ outlets by those who are the major emitters of fake news is part of a determined attack against the system of checks and balances which define and protect liberal democracy. The purpose is to delegitimize the ‘elites’, the ‘Establishment’. It is to weaken counter-powers and in particular legacy media which in the US case constitute one of the brakes on the impulsive matamorism of Donald Trump. In Germany too, attacks against the « lying press », a reminiscence from the Nazi years, or in France, the denigration of ‘merdia’ and ‘presstitute’ have a strategic aim: to discredit those who decode and denounce the lies of surging populist leaders and movements.

Fake news is also a revealer of our societies and their drifts. It is part of a digital universe which is at the same time fascinating and destabilizing. Words like phishing, spoofing, hacking, filter bubbles, testify to the anxiety which corrodes a digitalized world that cannot just be candidly described as liberating and empowering.

Fake news also reveals the state of opinion. It measures its knowledge and critical sense, or the lack of it. Post truth, writes the Oxford Dictionary, means that ‘objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’. One of the problems lies in the fact that part of public opinion does not seem to care about lies from personalities that it supports. Fact-ckecking bumps into a wall of mistrust and dogmas which the unquestionable presentation of verified facts cannot shake.

Much more fundamentally, as EU Commissioner Mariya Gabriel in charge of digital economy and society, said in an interview with Le Soir, ‘disinformation is also a political and a societal problem. Our societies’ vulnerabilities open the doors to disinformation. I am referring to unequalities, social fractures, mistrust in society and the rejection of elites’.

How can we explain the resurgence, especially among the young, of conspirationism, of an attraction for suspicious explanation of events? This phenomenon is the barometer of a loss of trust in institutions and not only in the education system and the media. It should lead to reflecting on the profound reasons of such disorientation and disarray. ‘Is not fake news a symptom rather than a cause of our crumbling democracies?’, asked François-Bernard Huyghe, founder of the Observatoire géostratégique de l’information en ligne (Paris).

Fake news also exposes the vulnerabilities and failings of our media system. In fact it should seriously alert us about significant developments in a sector which is crucial to democracy. The malaise which has gripped legacy media, deprived of a business model, the migration of a great part of the audience, the youth in particular, towards platforms like Facebook, threaten a media system which remains a crucial element in the democratic accountability process.

The focus on fake news, to the extent that it is described as information disseminated by adversaires or enemies, entails another risk: intolerance towards sources of information or opinions which we don’t like or find inconvenient.

RT and Sputnik news, for instance, are undoubtedly state media, of an authoritarian state, Russia, which has suffocated freedom of expression internally. They are undoubtedly tools of Russia’s strategy of influence with regard to the West. But should they be targeted by special measures aimed at excluding them from the democratic agora? Let us remember that authoritarian states, like terrorist or far right organizations, endeavor systematically to demonstrate that liberal democracy is a sham, a thin veneer covering a system of domination and exploitation. Banning them would be entering into a trap. The risk of witch hunts is never far away.

The rigorous assessment of the reach of fake news is a precondition to any reasoned and efficient response. Studies disagree on the place and the real impact of fake news. Their mode of production, their strategies of dissemination and the way they are received should be thoroughly and serenely studied.

The appeal to the responsibilisation of digital platforms appears evident. Some governments have put pressure on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Google and others to push them to police what remains their private domain and to excise the most extreme forms of disinformation. But there is a limit and a danger: converting these platforms in private censors, beyond the norms and guarantees of the rule of law. In September 2017, for instance, the World Socialist Website, a trotskyist media, estimated to have lost 70% of its search engine-led traffic because of a change introduced in April by Google.

Such risks imply a need to seriously question the hegemony of these platforms, which is, as much as or even more than fake news, a threat for democracy.

Fact-checking has become a household word in journalism. It is surprising that it is sometimes presented a specialized form of journalism where it should be a banal, obvious, element of all forms of journalism. It is undoubtedly more necessary today because of the bulk and the speed of information but if the purpose is to convince the gullible, it might not be efficient since it is being practiced mostly by these ‘stenographers of power’ who are accused by populists of ‘hiding the truth’.

Media literacy is again without doubt a crucial element. Most of the public does not master the media codes. It does not acknowledge the silos of certainties in which it encloses itself. Such media education, however, must cover all the media, even the video games, and should start very soon, with young children. And it must be part of a more comprehensive approach to education as such, of a permanent learning system and process which in all its expressions develops critical thinking, judgment and openness to diverse opinions. To scotch media literacy programs on failing or dogmatic schools will be vain.

Support to public interest media seems likewise essential. Now, in many European countries, public service broadcasting is on the defensive, when it does adopt itself populist practices which contradict their proclaimed values. However when they are well-conceived and protective of freedom, independence and pluralism, such support to media (public or private) « in the public interest » can really promote experiences and initiatives which go against the trends of disinformation and trivialization. Such measures should not benefit only legacy media but also to the web where the most decisive battles for the formation for public opinion are being fought.

Finally the fear of fake news should not become obsessive. It should not sub-estimate the capacity of citizens to identify falseness nor the capacity of journalism to renew itself, as has been demonstrated by the ICIJ (International consortium of investigative journalism) with its groundbreaking forms of collaborative transnational journalism projects.

It should not ‘relativise’ either the imperative for democracies not to over-react and the urgency to stay faithful to their most essential principles.

It has become banal to quote Benjamin Franklin’s famous (and contested) phrase: ‘those who would give up essential liberty, to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety’. It has become banal to quote it because the temptation to give in to censorship or control is increasingly present.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1513269834820-b5b02dbd-a0e2-0″ taxonomies=”8996″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Rachel Ehernfeld’s case highlighted the problem of “libel tourism” in English courts. Emily Badger got her reaction to the government’s proposed reforms

(more…)