Mouth Shut, Loud Shouts: Index at Marabouparken

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

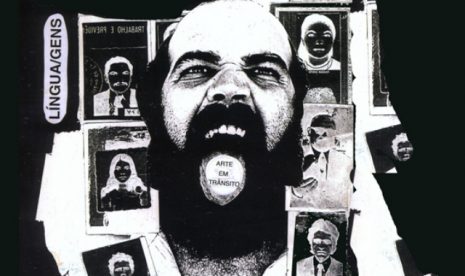

Foto: Paulo Bruscky

Lingua/gens: Tongue Performance 1996

© Konstnären och Galeria Nara Roesler

Mouth Shut, Loud Shouts is a new group exhibition at Stockholm’s Marabouparken that deals with questions of censorship and silencing deeply rooted in colonial regimes. The show will feature a reading room, which includes a selection of material from the Index on Censorship.

Mouth Shut, Loud Shouts have built a reading room to hold publications and material related to the exhibition, where attendees can spend time and read. A large part of the library is dedicated to Index on Censorship magazine, a global quarterly magazine, with reporters and contributing editors around the world. It was founded in 1972 by British poet and novelist Stephen Spender whose work focused on social injustice and class struggle. Alongside translator Michael Scammell they set up a magazine to publish the untold stories of dissidents behind the ‘Iron Curtain’ – the very first issue included a never-before-published poem, written while serving a sentence in a labour camp, by the Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and just this year it published a story by Haroldo Conti, which had never before been published in English. From the beginning, Index declared its mission to stand up for free expression as a fundamental human right for people everywhere. It was particularly vocal in its coverage of the oppressive military regimes of southern Europe and Latin America, but was also clear that freedom of expression was not only a problem in faraway dictatorships, and focused its reporting on the different ways censorship and freedom of expression operates across the whole globe.

The collection of magazines are part of an archive loaned by the Bishopsgate Institute in London, an important space for the preservation of material on the labour, cooperative, free thought, protest and LGBTQ movements since 1895.

A series of posters, free to be taken away can be found here. These new works are connected to a project called The Klinik whose aim is to bring together artists and cultural workers to discuss cases in the censoring of artistic expression. Johanna Gustavsson and Felice Hapetzeder have produced two new posters that respond to Klinik workshops held in Stockholm in Autumn 2106. On the 16 September Belit Sağ, Secil Yayali and Felice Hapetzeder will hold public workshops exploring different forms censorship activating questions of how censorship operates in the arts in Stockholm.

In addition, there are a number of publications which relate to questions the exhibition touches upon and the exhibiting artists and their work.

The suppression of speech, information, language and image is expansive and operates in different ways across the globe. Works within the exhibition present how censoring can operate as a mode of marginalisation and delegitimisaiton. Whilst some work directly opposes forms of state censorship, other works deal with pervasive embodied codes of self-censorship. Importantly the work looks to practices that transgress these modes of silencing and suppression, finding spaces, avenues and aesthetic forms that leak out voices to the world and ourselves.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

When: Opens 15 September 2017

Where: Marabouparken, Löfströmsvägen 8, Sundbyberg. [email protected]

Tickets: Free

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]