25 Sep 2020 | Opinion, Ruth's blog

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

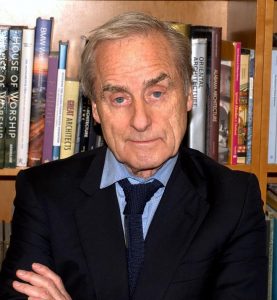

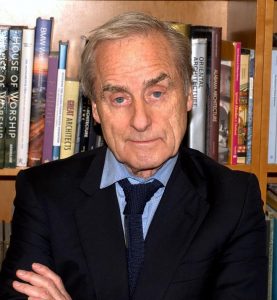

Index patron and friend Sir Harold Evans, photo; David Shankbone, CC BY 3.0

On Wednesday evening a legend passed away. Sir Harold Evans.

Harry wasn’t just a proper newspaper man, he was the staunchest of advocates for free speech both in the UK and across the world. But, most importantly, at least for us, he was part of the Index family, as a long-standing patron, friend and supporter.

Many people have written their personal stories of Harry in the last 48 hours, their experiences of a great man who embodied the best of journalism. A journalist who was fearless in challenging the establishment and shining a light on some of the most appalling scandals of his age, re-inventing investigative journalism, ensuring that his work changed minds and the law. A publisher who changed the political landscape.

Very few of us will leave such an awe-inspiring legacy.

Most importantly Harry was brave and was prepared to use his position to not only help others by exposing injustice but by ensuring that the voice of the victims was heard – most notably in his work with survivors of the thalidomide scandal.

From an Index perspective, Harry didn’t just seek to protect free speech, he relished using it. He was the first editor in British history to ignore a government D-notice, when he believed that the government were seeking not to protect national security but rather their own reputation. It’s because of him that we know the name of Kim Philby, the traitor who acted as a double agent. He stood up to the government and exposed a national scandal. In this, and on so many other issues, he published without fear or favour.

You can read Harry on the pages of Index writing about the censorship of photographs, anti-Semitism in the Middle East and forgotten free speech heroes. We were honoured to have his support and we are so saddened by his loss.

Our thoughts and prayers are with Harry’s family, friends and colleagues – may his memory be a blessing for all of them.[/vc_column_text][three_column_post title=”You might also like to read” category_id=”13527″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Jul 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, United Kingdom

(Image: Shutterstock)

I’ve occasionally thought it might be fun, even therapeutic, to have an enemies list. I would carry it in my pocket, a single, increasingly ragged B5 ruled sheet, on which I would scribble, with my specially purchased green Bic biro, the names of those who had taken against me, or to whom I had taken against; starting with the Ayatollah Khamenei (long story) and ending, well, never ending.

I could scrawl and scrawl, adding people and organisations: the wine waiter who mysteriously sneered “For you sir, perhaps a glass of Merlot” (I know that’s an insult, I just don’t know why that’s an insult), everyone who stands on the bottom deck of a bus when there are seats upstairs, the Communist Party of Vietnam, and so on, endlessly, ‘til my little scrap of paper was a grand mess of green ink, letters over letters over letters, upside down, vertical, horizontal, furious underlines, multiple exclamation marks, sometimes, just discernible, the word “NO” in capital letters.

It would be good to have the list at hand, to have it under control, I imagine. As long as I’ve got them all written down, and the list is on my person, I won’t be caught off guard. This would not be odd, you agree. It would be an entirely reasonable thing to do in a world where foes stalk us, waiting to mug us, or make us look like mugs.

For politicians, this sense of the entire world waiting for the moment you mess up is amplified, partly because it is a reflection of the truth. Opposition activists will pick up on every word you say, and the slightest slip will be turned into a hilarious/earth-shatteringly dull meme in mere minutes, with earnest young women imploring people to retweet whatever the hell it was that proves you hate nurses/the nuclear family/your party leader, and proves you’re not fit to do XYZ.

And then there’s the “feral beasts” of the press, as Tony Blair famously referred to journalists in 2007 (this was literally worn as a badge of pride by many: the New Statesman’s then political editor had “Feral Beast” badges made, which he handed out to every journalist he met), who you spend your life trying to please while deep down knowing they are willing you to cock up. You really, really can’t win.

Faced with all this, it’s not surprising that politicians and politicos are a little wary of the world. But there is a difference between wariness and paranoia, a difference demonstrated by the reaction to the Sunday Times’s report of a speech delivered recently by Labour’s Jon Cruddas to the left-wing group Compass. An attendee of the publicly advertised meeting passed a recording of Cruddas’s comments to the Sunday Times. The journalist then had the temerity to report on the speech! According to the Telegraph’s Stephen Bush, Cruddas’s next appearance, at the Fabian Society Summer Conference, was “bad tempered” and full of attacks on the “‘herberts’ and ‘muppets’ of Fleet Street who might be listening to his every word or statement in search of a headline”.

Meanwhile Neal Lawson, Compass chairman and Cruddas’s host, wrote a strange article for the Guardian, suggesting, somehow, that Cruddas’s comments were not in the public interest, and somewhat hyperbolically claiming: “The Sunday Times got its cheap splash, but in the process our political culture is diminished, maybe fatally.”

Lawson then really went for it, claiming: “What happens next? We either accept that the Murdoch empire — and maybe others — make toxic yet another level of public life and succeed in shrivelling our body politic still further. Or we make whatever stand we can.

Their goal is not just to destroy Labour or even any alternative to the individualistic, me-first politics of the past 30 years. They want to destroy the possibility of such an alternative. Invading the spaces in which such an alternative is discussed, such as the Compass event, is just a means to an end.”

All this at first reads as merely silly, but there are a few strands in it that are quite worrying. The first is the idea that a journalist reporting on a public meeting (Lawson’s justification for claiming it was “semi-private” was that attendees had to register and there was no press list) is fatally undermining democracy. There is an authoritarian undertone to this: journalists should report on what we allow them to report, not what is of interest. This is also reflected in Lawson’s comment about journalistic practices — “For the papers who do this it’s an easy, cheap hit: no research, no digging, just someone with a smartphone who is willing to sit through boring meetings on a Saturday afternoon” — somehow the story is not a good one because it was gained through day-to-day processes rather than via the Woodward-And-Bernstein routines that are seen as “proper” “investigative” journalism.

Secondly, there is the Murdochophobia which escalates an agenda to a conspiracy: The Sunday Times and Murdoch’s other papers are broadly conservative, it is true, but that’s a long way from having a goal of “destroying Labour” (a party Murdoch’s papers supported for a long time).

The problem with this paranoid mindset is that nobody takes responsibility for their own actions or even their own opinions. The question of whether there is a problem with Labour policy or not, becomes simply evil newspaper versus innocent, naive, poor little politician. It is self-pitying and self-defeating. Either have the debate, or don’t. But don’t complain when reporters report.

This article was posted on July 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

30 Jan 2013 | Uncategorized

Sunday Times editor Martin Ivens yesterday issued an apology for publishing a cartoon by Gerald Scarfe depicting Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu.

The cartoon, which appeared in the paper as Britain marked Holocaust Memorial Day, showed the Israeli leader building a wall, and crushing Palestinians in the process. With its blood splashes and thuggish, brawny depiction of Netanyahu, the cartoon was, in the words of a Sunday Times spokesperson (before the apology), a “typically robust” piece of work by Scarfe.

The editor’s apology came after public criticism from his proprietor, Rupert Murdoch, who tweeted “Gerald Scarfe has never reflected the opinions of the Sunday Times. Nevertheless, we owe major apology for grotesque, offensive cartoon.”

It does seem slightly odd to apologise for a “grotesque, offensive” cartoon. As Martin Rowson (who draws strips for Index on Censorship magazine) points out in this article, and this Free Speech Bites podcast, cartoons are usually, by their very nature grotesque, and often offensive (to borrow a phrase from Woody Allen, at least if they’re done right).

Did this cartoon, however, cross a line? Lord Sacks, the chief rabbi, put out a statement, saying:

“The deplorable cartoon published in The Sunday Times on Holocaust Memorial Day, whether antisemitic or not, has caused immense pain to the Jewish community in the UK and around the world. Whatever the intention, the danger of such images is that they reinforce a great slander of our time: that Jews, victims of the Holocaust, are now perpetrators of a similar crime against the Palestinians. Not only is this manifestly untrue, it is also inflammatory and deeply dangerous.”

But Israeli journalist Anshel Pfeffer at Ha’aretz says that, while it may have been unpleasant, it did not contain any of the anti-Semitic blood libel and Nazi imagery that characterises genuinely Jew-hating cartoons.

Moreover, Scarfe has not notably singled out the Israeli leader for special treatment — a glance through the cartoonists archives shows portrayals of many equally blood-spattered world leaders (take, for example, this horrendous but riveting image of Bashar Al Assad, drenched in the blood of children)

Scarfe has apologised for the timing of the cartoon, though some, including Pfeffer, will say that Israeli leaders should not be immune from criticism on Holocaust Memorial Day.

Context is crucial in any debate over free speech and offence.

In 1981, far-right cartoonist Robert Edwards was given a 12-month sentence for “”aiding and abetting, counselling and procuring the publication of material likely to incite racial hatred”.

Robert Edwards’s work was unsubtle to say the least. The conviction came after the one off publication of a comic aimed at children called “The Stormer” (I did say he was unsubtle). The comic contained such delights as “”Billy the Yid”, and “Dresden and Auschwitz — The Facts!”, as well as strips targeting black and Asian people.

More recently, in 2009, Simon Shepherd and Stephen Whittle were convicted for several offences including pushing a leaflet entitled Tales of the Holohoax through the door of a Blackpool synagogue.

It is clear that Scarfe’s blood-spattered commentary on Netanyahu was quite different to the output of Edwards, Whittle and Shepherd (and there is another discussion to be had about free speech in those cases).

As such the intervention by 20 MPs writing a letter demanding an apology from the Sunday Times is a dismayingly knee-jerk reaction. As was Murdoch’s tweet.

At Index on Censorship’s Taking the Offensive conference yesterday, hundreds of artists discussed their fears of expressing themselves, lest they fall foul of local politicians, commercial sponsors, community leaders or even a Twitter mob. The censorious will always tend towards the literal, a mindset rather unsuited to the reading of the exaggerated, ironic world of art, including political cartooning.

25 Jan 2012 | Leveson Inquiry

Investigative reporter Mazher Mahmood was recalled to the Leveson Inquiry today and quizzed over the reasons for his 1989 departure from the Sunday Times.

Mahmood, also known as the Fake Sheikh for the disguise he wears while investigating, told the Inquiry in December that he and then managing editor (news) Roy Greenslade had “had a disagreement”.

In a blog post written after Mahmood’s first appearance at the Inquiry, Greenslade wrote that Mahmood had “falsely blamed the news agency and then tried to back up his version of events by entering the room containing the main frame computer in order to alter the original copy.”

Having been found out, Greenslade wrote, Mahmood “rightly understood that he would have been dismissed” and so wrote a letter of resignation.

Mahmood, who returned to the Sunday Times last autumn after the News of the World closed in July 2011, regretfully admitted today that he “foolishly” tried to blame the news agency for his mistake.

He added later that a recent claim made by former Sunday Times news editor Michael Williams that Mahmood had offered a financial bribe to staff in the newspaper computer room to falsify his copy was “completely untrue”.

Mahmood told the Inquiry that Greenslade has since been “very critical” of his investigations: “Ever since he has displayed obsessive hostility towards me. There were run-ins over several stories.”

Tuning into the Inquiry, Greenslade tweeted:

Grilled by Lord Justice Leveson and counsel David Barr on the reliability of his sources, Mahmood said: “I’ve had front-page splashes from crack addicts, prostitutes, all sorts of sources”, adding that “one crack addict stole my tape recorder.”

A prosecution arising from Mahmood’s 2002 News of the World splash claiming there was a plot to kidnap Victoria Beckham was dropped when prosecution lawyers decided that Florim Gashi, the key witness (one of Mahmood’s sources), was unreliable.

Also appearing this morning was RMT union leader Bob Crow, who claimed his union had been a victim of “victimisation”. He described being doorstepped by reporters and photographers from the Sun, who said to him: “What’s it like not to get to go to work? You stopped people going to work this week so get a taste of your own medicine.”

He was also asked about a Mail on Sunday story from 2003 showing that he had got a scooter to work owing to tube failures. The Inquiry was told that the registration identity of the scooter was blagged from the DVLA and then passed on to private investigator Steve Whittamore, who passed it on to the paper.

Follow Index on Censorship’s coverage of the Leveson Inquiry on Twitter – @IndexLeveson