Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Index on Censorship is extremely concerned about the reported extent of mass surveillance of both meta data and content, resulting from the alleged tapping into underwater cables that carry national and international communications traffic.

Index calls on the UK government to clarify the extent and legality of the alleged surveillance by GCHQ. Index believes that GCHQ is circumventing laws such as the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) to allow surveillance that undermines the human rights of British and other citizens.

Index CEO Kirsty Hughes said:

“The mass surveillance of citizens’ private communications is unacceptable – it both invades privacy and threatens freedom of expression. The government cannot continue to cite national security as a justification without revealing the extent of its intrusion and the legal basis for collecting data on this scale. Undermining freedom of expression through mass surveillance is more likely to endanger than defend our security.”

Index is calling on the British government to:

• Confirm whether GCHQ is undertaking the mass surveillance of meta data and content by tapping into communications cables

• Clarify which laws are being used to authorise the collection of data by this method and on this scale

• Commit to protecting the right to privacy and to freedom of expression of people living in the UK and beyond

By Seth Masket / Pacific Standard

David Simon, the creator of HBO’s epic series The Wire, has weighed in on the recent disclosure that the National Security Agency has been combing through our cell phone records as part of its anti-terrorism efforts. It’s an interesting read, particularly coming from the guy who wrote such interesting stories (presumably based on what he saw as a crime reporter for the Baltimore Sun) about police surveillance. Basically, his take is that using broad swathes of cell phone data (numbers dialed, minutes used, locations, etc.) is not particularly invasive, is perfectly legal, and has been a regular tool of law enforcement since well before 9/11.

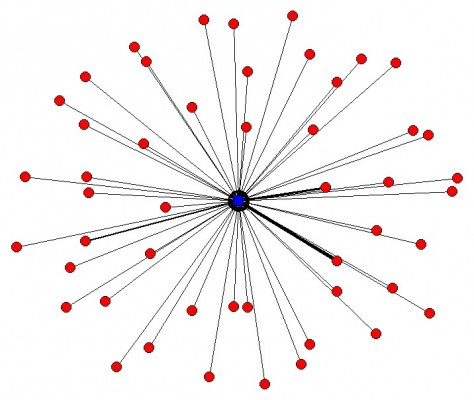

How might this be a useful law enforcement tool? To illustrate, I took the liberty of downloading my own cell usage data from the past month from Verizon. Below is a type of network graph called an “egonet” showing my cell phone conversations during the month of May. I’m at the center (the “ego”), and all the red dots (the “alters”) are people to whom I’ve spoken. (No, the points aren’t labeled.) Thicker lines indicate more frequent phone contacts.

You can see that most of the contacts are people I speak to only once or twice. The highlighted (more frequent) connections are my wife, my parents, my brother, a colleague, my kids’ elementary school, and a guy who was doing some contract work at my house. Let’s just assume that’s a typical phone data pattern for a guy in my demographic profile who’s not a terrorist. (You’ll have to take my word for this.)

Now, if you were able to download the phone usage data for all the nodes depicted above and graph them, you’d have a pretty complex network diagram. It would show some small, dense networks (families, groups of friends) and some loosely-affiliated people who have their own connections. Now download the phone usage data for all of those nodes, and imagine the patterns it would show. Now imagine if you could do that for basically every cell phone subscriber in the country.

That’s a huge amount of data, and depicting it graphically would pretty much be a waste of ink. Profiles like mine would quickly disappear into background noise. But computers can look for people who rise above the noise. Perhaps someone seems to belong to no local networks but just pops up to make a few phone calls that last less than a minute. Perhaps those calls occur within 24 hours of a bombing attack, or right after an al Qaeda speech is broadcast. Well, that’s hardly proof of criminal activity, but it might be enough for investigators to seek a warrant for a wiretap or some other form of surveillance to learn more about the person making the calls.

This is related to another point Simon makes in his post: There’s no reason to believe that the government is listening in on all of our phone calls, simply because the task is absurdly vast. What percentage of us are engaged in criminal conspiracies at any given moment? For investigators to somehow monitor all our phone calls to see if we’re doing anything wrong is ridiculous: the signal-to-noise ratio is functionally zero. It would be more efficient to just walk door to door asking if we’re doing anything illegal.

What the big data approach described above does is avoid the task of monitoring everything at once. It uses networking patterns to filter out the noise and find the few individuals who are behaving atypically, and focus on them.

Now, I’m not saying this is how the NSA actually operates; I really don’t know. Nor am I saying that this is how it should operate. Just consider this an educated guess as to how a law enforcement organization would use this kind of data if it were available.

This article originally appeared at Pacific Standard. Pacific Standard is an arm of the nonprofit Miller-McCune Center for Research, Media and Public Policy. Seth Masket is a political scientist at the University of Denver, specializing in political parties, state legislatures, campaigns and elections, and social networks. He is the author of No Middle Ground: How Informal Party Organizations Control Nominations and Polarize Legislatures (University of Michigan Press, 2009). He tweets at @smotus.

(Photo: Andrei Aliaksandru/Index on Censorship)

Against a backdrop of ongoing revelations around the US Prism programme, mass surveillance dominated the discussion at the Index on Censorship event Caught in the web: How free are we online? Brian Pellot reports

Index on Censorship brought together a panel of experts at King’s Place in London last night. Investigative journalist Heather Brooke, author and digital rights activist Cory Doctorow, media lawyer Paul Tweed, Index CEO Kirsty Hughes and chair David Aaronovitch discussed the threats to freedom of expression online.

Brooke, warned that as we increase our online expression, we “create a handy one-stop shop for snooping officials”. She also cautioned that concentrated power in secretive states is a far greater danger to humanity than unbridled free speech.

(Brooke, author of The Revolution will be Digitised, kindly joined the panel at the last minute, replacing Guardian data editor James Ball, who is currently in the US covering the developing Prism scandal)

Doctorow, co-founder of the hugely influential Boing Boing blog, said while he was pessimistic about the “Orwellian control” that digital technologies provide governments, he remains optimistic that such technologies can enable us to cooperate, coordinate and collaborate in unprecedented ways to seek positive social change.

Doctorow questioned the efficacy of overcollection of data, characterised by PRISM, saying that as an intelligence technique is “like pointing at a pixel with a hotdog”.

Belfast-based libel lawyer Tweed said that anonymity online enables speech that constitutes dangerous harassment. He argued that freedom of expression must be protected, but that controls are needed to prevent the undermining of reputation and privacy. He recounted examples from his practice of clients that are harassed and attacked on the web with very little recourse against “internet goliaths”.

“There has to be a button to protect the man on the street”, Tweed said.

Hughes discussed the emerging geopolitics of digital freedom, noting that while EU countries and the US are lobbying for the preservation of a multistakeholder model of internet governance, Russia, China and others are pushing for top-down government control. Some of the greatest threats to online freedom of expression she discussed are censorship in the form of firewalls and filters, laws criminalising offence, the privatisation of censorship and, of course, surveillance.

Aaronovitch fielded questions from audience members who were focused on government surveillance and censorship.

Doctorow claimed that web filters are a blunt and inefficient instrument, giving the example of Denmark’s secret child abuse filters, which leaks showed had blocked a huge amount of material that was not related to sexual imagery of children.

“Everyone knows web filters don’t work, but once used, removing them would be political suicide,” he said.

Brooke acknowledged that current laws are not keeping pace with technology but does not think new laws are the solution. More important is that “our fundamental values be translated into the digital age”, she said.

“Nothing to hide, nothing to fear is an arrogant statement”, Brooke commented on UK foreign secretary William Hague’s response to questions on PRISM on Sunday.

Hughes elaborated on a statement she made earlier in the day essentially saying that mass surveillance is an invasion of our right to privacy and a direct chill on free speech.

Index on Censorship has released a joint statement with English PEN, Privacy International and Open Rights Group condemning the use of national security to justify mass surveillance.

Let us know your thoughts on the Prism scandal by commenting below

Related:

• Pod Academy coverage of this event

It’s been a rocky week for government surveillance and freedom of expression, Brian Pellot writes

On Tuesday, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression Frank La Rue delivered a report to the Human Rights Council outlining how state and corporate surveillance undermine freedom of expression and privacy. The report traces how state monitoring has kept pace with new technological developments and describes how states are “lowering the threshold and increasing the justifications” for surveillance, both domestically and beyond their own borders.

The true depths of this lowered threshold were exposed on Thursday, when The Guardian revealed that the US National Security Agency has been collecting call records of Verizon’s millions of subscribers. Things got worse on Friday when reports alleged the same agency can access the servers of Google, Facebook, Apple, Yahoo, Microsoft and others to monitor users’ video calls, search histories, live chats, and emails. It was long one of Washington’s worst kept secrets that data about our communications (call logs, times, locations, etc.) were being monitored, but the revelation that the government has granted itself, without democratic consent, the ability to monitor the actual contents of our communications is appalling.

Related: ‘Mass surveillance is never justified’ — Kirsty Hughes, Index on Censorship CEO

Today on Index

The EU must take action on Turkey | Iran tightens the screw on free expression ahead of presidential election

Index Events

Caught in the Web: How free are we online?

The internet: free open space, wild wild west, or totalitarian state? However you view the web, in today’s world it is bringing both opportunities and threats for free expression — and ample opportunity for government surveillance

Mass surveillance programmes have awful implications for freedom of expression. Index on Censorship made this clear in regards to the UK’s proposed Communications Data Bill last year. States should only limit freedom of expression when absolutely necessary to preserve national security or public order. In such exceptional cases, limits on expression should be transparent, limited and proportionate. La Rue’s latest report adds that states should not retain information purely for surveillance purposes. The US programmes revealed this week grossly violate all of these principles.

Surveillance is, by its very definition, a violation of privacy. La Rue’s report rightly states that “Privacy and freedom of expression are interlinked and mutually dependent; an infringement upon one can be both the cause and consequence of an infringement upon the other.” Without some guarantee or at least a (false) assumption of privacy online, we cannot and will not express ourselves freely. Mass surveillance programmes directly chill free speech and give rise to self-censorship.

If the top secret documents outlining these programmes were leaked, what’s to stop our top secret personal information, that which is being monitored by government agencies, from being exposed? These programmes and even more extreme efforts to limit freedom of expression online in other states are unjustified, disproportionate, secretive and often without adequate limits. La Rue’s report calls for national laws around state surveillance to be revised in accordance with human rights standards.

Brian Pellot is Digital Policy Advisor at Index on Censorship.