19 Dec 2017 | Journalism Toolbox Russian

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Иностранные корреспонденты часто полагаются на “посредников“, которые помогают собирать информацию о пострадавших от войны странах. Но, как свидетельствует Кэролайн Лиз, эти «посредники» могут оказаться под прицелом как шпионы, если их имена станут известными.”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Украинские журналисты на пресс-конференции в посольстве США, US Embassy Kiev Ukraine/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Раванд постоянно рискует своей жизнью ради незнакомцев. 25-летний студент факультета компьютерных технологий работает в качестве «посредника», оказывая поддержку иностранным корреспондентам в Эрбиле, Ирак. Город всего лишь в часе езды от оккупированного Мосула. В июне исламское государство угрожало расправиться с журналистами “воюющими против ислама”.

“Давайте представим, что ИГ захватило Эрбиль. Первые люди, которых они будут искать — это «посредники», — говорит Раванд, который работал с новостями «Вайс» и журналом «Таймз». “После докладов “посредник” остается в стране, а у репортера есть иностранный паспорт и может уехать”, — добавляет он.

Посредники занимаются логистикой для иностранных корреспондентов, включая устный перевод и услуги гида; они исследуют, наращивают контакты, проводят собеседования и выезжают на передовые. Большинство из них — внештатные сотрудники, которые подвергаются угрозам и репрессиям, особенно после отъезда иностранных коллег. Согласно Рори Пек Трасту, организации, которая поддерживает внештатных работников во всем мире, количество подверженных угрозам местных внештатных журналистов, которые сотрудничают с международными средствами массовой информации, увеличивается.

“Большинство просьб о нашей поддержке поступает от местных внештатных сотрудников, которые подверглись опасности, задержанию, тюремному заключению, нападению или к изгнанию из-за своей работы”, — говорит Молли Кларк, руководитель отдела коммуникации в Рори Пек. “Мы регулярно поддерживаем тех, кто подвергается опасности обусловленной сотрудничеством с международными средствами массовой информации. И в этих случаях последствия могут быть разрушительными и долгосрочными – не только для них, но и для их семей” — добавляет Кларк.

Комитет по защите журналистов сообщает, что 94 работника средств массовой информации” были убиты с 2003 года: с того времени, когда КПЖ начал осознанно относится к «посредникам», убеждаясь во все возрастающей значимости их репортажей для иностранных сводок новостей. В июне этого года Забихуллах Таманна, афганский внештатный журналист, работавший переводчиком для американского общественного радио, был зарегистрирован в списке КПЖ как погибший. Конвой, в котором он передвигался, был взорван в Афганистане.

В странах, пострадавших от конфликтов, многие «посредники» начинают работать как неопытные любители, отчаянно нуждающиеся в работе. Они редко получают профессиональную подготовку или долгосрочную поддержку со стороны международных организаций, на которые они работают, и зачастую сами несут ответственность за свою безопасность. Раванд научился не высовывать свой нос в Эрбиле. Он редко помещает своё имя, подписывается под докладом или статьёй, над которыми он работал. “Если моё имя окажется под репортажами, его все узнают. Меня начнут подозревать и будут считать шпионом”, — говорит он.

Самый большой профессиональный риск для многих «посредников», работающих с иностранными журналистами – обвинение в шпионаже. Для тех, кто работает на передовых линиях военного конфликта между Украиной и российскими сепаратистами – это повседневная угроза. В 2014 Антон Скиба, местный донецкий продюсер, был похищен сепаратистами. Его обвинили в том, что он украинский шпион. Он отработал день с CNN на месте аварии самолёта МХ17 авиакомпании «Малазийские Авиалинии». Авиалайнер был сбит в восточной части Украины, на контролируемой сепаратистами территории. Вследствие освободительной акции коллег-журналистов, Скиба, который также работал на BBC, в конечном итоге был освобожден. “Действительно важно оставаться объективным, когда у вас есть доступ к обеим сторонам конфликта; в противном случае существует высокая вероятность того, что одна из сторон будет на вас притеснять”, — говорит он.

Скиба пытается защитить себя, осторожничая и с людьми, с которыми работает, и с исследуемым материалом. “Это моя страна, и я останусь жить здесь после того, как журналисты переключат своё внимание на другой конфликт.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Я не хочу рисковать своей жизнью ради репортажа, который забудут на следующий день. Вот почему я стараюсь избегать непрофессиональных журналистов и тех, которые используют «посредников» для получения “горячих новостей»», — говорит он.

Другой донецкий «посредник», Катерина, получила аккредитацию от украинских властей и от оппозиционной сепаратистской Донецкой Народной Республики, с тем, чтобы её не обвинили в предвзятом отношении к одной из сторон.

Это не остановило ни угроз, ни домогательства. Она не обнародует свое сотрудничество с международными журналистами. Однако недавно, украинский веб-сайт «Миротворец» опубликовал имена, электронные адреса и номера телефонов около 5000 иностранных и местных журналистов, работавших в ДНР и Луганске – отколовшихся районах, неподконтрольных правительству Украины. Имя Катерины, 28, несколько раз было представлено в списке, опубликованном в мае 2016, потому что она работала с BBC, Аль-Джазирой и другими СМИ. Служба безопасности Украины постоянно подвергает Катерину задержаниям и допросам, связанным с ее работой. “После двух лет работы с иностранными СМИ, вы в центре внимания служб безопасности”, — говорит она. “И лучше не недооценивать их силу. Они достаточно умны, чтобы играть твоей жизнью”. В Донецке Катерина чувствует себя в опасности, и она хотела бы найти другую работу. “Как только телевизионная команда уедет, я не буду больше этим заниматься”— говорит она. “Только однажды я ощутила заботу со стороны международных СМИ. Только однажды я ощутила заботу со стороны международных СМИ. В мае этого года после публикации моего имени в «Миротворце», коллега с BBC спросил меня, нуждаюсь ли я в поддержке. Я отказалась от помощи, потому что это было не самое ужасное, что могло случиться со мной”.

Немногие «посредники» имеют право на компенсацию, если они будут ранены или убиты во время работы. Они также не имеют фактической международной защиты, которая обычно распространяется на иностранных журналистов, работающих за рубежом. Только в Афганистане десятки письменных переводчиков, водителей и местных режиссеров погибли в период между 2003и 2011 годами, некоторые из них попали в боевые действия, другие, такие как Ажмал Накшбанди, журналист и Сайед Ага, водитель, подверглись казни талибами за работу с иностранцами.

Саира, «посредница» в Кабуле, Афганистан, на протяжении последних девяти лет, может работать только в том случае, если она скрывает и свою личность, и скрывается свою внешность. Ей постоянно угрожают и оскорбляют. Она так боится мести, что не разрешила использовать своё настоящее имя в этой статье. 26-летняя девушка, которая начала свое сотрудничество с иностранными журналистами, чтобы иметь возможность оплатить свою учебу в Кабульском университете, говорит, что чувствует себя в безопасности только тогда, когда ее лицо закрыто паранджой. “Я путешествовала по некоторым опасным местам с иностранными журналистами. Я должна была полностью закрыть свое лицо паранджой, чтобы чувствовать себя в безопасности”, — говорит она.

“Для женщины всегда опасно работать, даже в Кабуле. Они осуждаются обществом и их не уважают. Многие люди обвиняют тебя и даже называет неверной, поскольку ты работаешь с не-мусульманами”, — говорит Саира. В зонах конфликтов, слишком опасных для зарубежных журналистов, «посредников» нанимают для написания и сдачи новостей непосредственно в офисы международных СМИ. “Всё больше и больше используются местные внештатники для репортажей, новостей и фотографий в странах и районах, где трудно или слишком опасно [для международных журналистов] получить доступ”, — говорит Кларк. “У нас нет каких-либо конкретных фактов или цифр, наши доказательства в основном являются неофициальными: то, что мы слышали и наблюдали в нашей работе”.

Алмигдад Можалли был «посредником», который впоследствии, когда война в Йемене вынудила многих иностранцев покинуть страну, стал репортёром. Можалли, 34, хорошо говорил на английском, знал нужных людей, был уважаем и востребован. Можалли предпочитал работать анонимно. “Ему нравилось быть «посредником», это предоставляло ему возможность озвучивать истории, которых он не мог бы безопасно рассказать в Йемене”, — говорит Лора Баттаглиа, итальянская журналистка, которая работала с ним и стала его другом. “С его согласия мы не указывали его имени в неоднозначных статьях, для его же безопасности”.

Но когда Можалли начал представлять отчеты самостоятельно, у него начались проблемы с Хауси ополченцами — повстанческой группировкой, которая контролирует столицу Йемена, Сана. Самый первый его репортаж, поданный в Бюро новостей в Европе и США под его же собственным именем, разозлила эту группировку. Его немедленно арестовали и ему угрожали правительственные агенты. В январе этого года, выполняя задания «Голоса Америки», он был убит при обстреле с воздуха. Он путешествовал в опасном районе, в автомобиле без маркировки, без каких-либо указаний на то, что он был журналистом.

Смерть Можалли заострила вопрос ответственности. Он был внештатным сотрудником, но работал в местах для международных информационных организаций. Майк Гаррод, являющийся соучредителем ‘’Мирового Посредника’’, онлайновой сети, которая связывает местных журналистов и внештатных работников с международными журналистами, считает, что некоторые группы средств массовой информации начинают более осознанно относиться к обеспечению безопасности внештатных сотрудников, которым они предлагают работу.

Гаррод надеется создать учебную программу в режиме онлайн для местных журналистов и «посредников». Этот курс будет включать оценку риска, и безопасности, а также журналистские стандарты и этику. «Посредники» в основном не обучены и уязвимы в враждебных условиях. Поскольку их все более используют не только в качестве письменных переводчиков и материально-технического обеспечения, то существует реальная необходимость того, чтобы они понимали и смогли доказать понимание некоторых концепций”, — говорит Гаррод. Авторы этой статьи задали вопросы BBC, CNN и агентству по поводу их политики касательно «посредников». Никто из них не пожелал прокомментировать эту ситуацию.

Согласно Гарроду, поведение некоторых журналистов, которые используют «посредников» на местах, сложнее регулировать. Он рассказал историю молодого студента, которому было 17 лет. Его нанял иностранный репортер, чтобы он отправился на передовую в Ираке. “Эта отрасль может сделать много, для того, чтобы поощрить ответственный подход журналистов. Но я беспокоюсь о том, что никто не будет разбираться, кто и как раздобыл материал для статьи”, — говорит он.

Зия Ур Рехман, 35, работал с иностранными корреспондентами в Карачи, Пакистан, с 2011 по 2015 год. Он рассказывает, что, хотя местные журналисты в городе понимают опасности, которые их поджидают, некоторые иностранные корреспонденты игнорируют их советы. “Бывает операторы и фотографы обращаются с «посредником» невоспитанно и грубо, как со своей прислугой. Поскольку они не знают о сложности и деликатности ситуации, они снимают фильмы или делают снимки без консультаций с «посредником». И это создает большие проблемы для группы, и особенно для «посредника»”, — говорит Рехман. Случалось, что пакистанские службы безопасности похищали, избивали и даже пытали «посредников» в связи с их работой с иностранными журналистами. Рехман говорит, что теперь он редко работает в качестве «посредника», и только, если он знает репортёра.

Более профессиональная подготовка и поддержка со стороны международных организаций, на которые работают посредники, имеют решающее значение для их безопасности, однако маловероятно, что они будут влиять на зоны, всё ещё контролируемые Исламским Государством. Эти группировки полны решимости заставить замолчать журналистов, особенно тех, кто работает с иностранными заказчиками. В июне этого года КЗЖ (ред. – Комитет по Защите Журналистов) сообщил, что в Сирии казнили пять внештатных репортёров. Одного привязали к ноутбуку, другого к камере, обеих напичкали взрывчаткой, и подорвали. Их обвинили в работе с зарубежными СМИ и организациями по правам человека. ИГ слил видеосюжеты их убийств как предостережение для других.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Кэролайн Лиз – бывший корреспондент британской газеты «Санди Таймз» в Южной Азии. В настоящее время она работает в научно-исследовательском институте агентства Рейтер по изучению журналистики в Оксфордском университете.

* некоторые имена в этой статье были изменены из соображений безопасности

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Dec 2017 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”A menudo los corresponsales en el extranjero tienen que ayudarse de guías (fixers en inglés), para informar desde países asolados por la guerra. Sin embargo, como revela Caroline Lees, estos pueden terminar en el punto de mira por espionaje si sus nombres se hacen conocidos en la zona”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Periodistas ucranianos toman asiento en una conferencia de prensa de la embajada de EE.UU, US Embassy Kiev Ukraine/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rauand arriesga la vida por desconocidos habitualmente. Este estudiante de informática de 25 años trabaja de guía: un tipo de periodista local que colabora con corresponsales extranjeros en Erbil, Irak. La ciudad está a solo una hora en coche de Mosul, ciudad bajo ocupación del Estado Islámico. En junio, el EI amenazó con matar a los periodistas «que hacen la guerra contra el Islam».

«Imagina que el EI llega a Erbil. Pues los guías serían los primeros a por los que irían», asegura Rauand, que ha trabajado para Vice News y la revista Time. «Al terminar los reportajes, el guía se queda en el país, mientras que el corresponsal, con su pasaporte extranjero, se puede marchar», añade.

Los guías llevan la logística para corresponsales extranjeros guiándolos y traduciendo para ellos, pero también investigan para artículos, adquieren contactos, organizan entrevistas y viajan al frente. La mayoría trabajan de forma independiente y son extremadamente vulnerables a amenazas y represalias, especialmente una vez se marchan sus colegas extranjeros. Según la organización Rory Peck Trust, que se dedica a apoyar a periodistas freelance alrededor del mundo, la cifra de reporteros independientes amenazados por colaborar con medios internacionales va en aumento.

«La mayoría de las peticiones de ayuda que recibimos nos llegan de reporteros locales que han sufrido amenazas, detenciones, prisión, asaltos e incluso el exilio por su trabajo», explica Molly Clarke, jefe de comunicaciones de Rory Peck. «Habitualmente ayudamos a gente a la que han atacado específicamente por su trabajo de colaboración con medios internacionales. En estos casos, las consecuencias pueden ser devastadoras y duraderas, y no solo para ellos: para sus familias también», denuncia Clarke.

Un informe del Comité para la Protección de los Periodistas —CPJ, por sus siglas en inglés— muestra que son 94 los «trabajadores de medios de comunicación» asesinados desde 2003: esta es la fecha en la que el CPJ comenzó a poner a los guías en una categoría aparte, como reconocimiento a la importancia creciente de estos en la transmisión de reportajes desde el extranjero. En junio de este año añadieron a Zabihulah Tamana, un periodista independiente afgano que trabajaba como traductor para la radio pública nacional de EE.UU., a la lista de asesinados cuando bombardearon el convoy en el que viajaba en Afganistán.

Muchos guías empiezan como aficionados sin experiencia, desesperados por conseguir trabajo remunerado en economías perjudicadas por los conflictos. Apenas reciben formación o apoyo continuado por parte de las organizaciones internacionales para las que trabajan, y a menudo deben encargarse de su propia protección. Rauand ha aprendido a no destacar en Erbil. Rara vez opta por firmar con su nombre los reportajes y artículos en los que contribuye. «Si mi nombre sale asociado a los artículos, ya no soy anónimo. Podrían sospechar de mí y tratarme como si fuera un espía», dijo.

Ser acusado de espionaje es un riesgo laboral para muchos de los guías que trabajan con periodistas extranjeros. Para aquellos trabajando en primera línea en la guerra entre Ucrania y los separatistas prorrusos, se trata de una amenaza diaria. En 2014, Anton Skiba, un productor local radicado en Donetsk, fue secuestrado por los separatistas y acusado de ser un espía ucraniano. Había pasado el día trabajando para la CNN en el lugar donde se estrelló el vuelo MH17 de Malaysian Airlines, en el este Ucrania, controlado por los separatistas. Skiba, que también ha trabajado para la BBC, fue finalmente liberado tras una campaña que organizaron sus compañeros del gremio. «Es muy importante mantener un equilibrio mientras tengas acceso a ambos lados del conflicto. De otro modo, lo más seguro es que uno de ellos acabe oprimiéndote», afirma.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Skiba trata de protegerse eligiendo con cuidado a la gente con la que trabaja y las noticias que cubre. «Este es mi país y yo tengo que seguir viviendo aquí cuando los periodistas pasen al siguiente conflicto. No quiero arriesgar mi vida por una historia que al día siguiente ya no va a recordar nadie. Por eso intento evitar a periodistas poco profesionales y a los que usan a guías para que les consigan noticias ‘jugosas», dice.

Kateryna, otra guía de Donetsk, obtuvo acreditación de prensa tanto de las autoridades ucranianas como de la facción separatista enemiga, la República Popular de Donetsk, para evitar acusaciones de favorecer uno de los lados de la guerra más que al otro.

Pero esto no ha puesto fin a las amenazas y ni al acoso que sufre. Aunque nunca le dice a nadie que trabaja con periodistas internacionales, una página web ucraniana, Myrotvorets, reveló recientemente los nombres, direcciones de correo electrónico y números de teléfono de alrededor de 5000 periodistas extranjeros y autóctonos que han trabajado en la República Popular de Donetsk y en Luhansk, áreas disidentes fuera del control del gobierno ucraniano. Kateryna, de 28 años, aparecía varias veces en la lista, publicada en mayo de 2016, debido a su trabajo con la BBC, Al Jazeera y otros medios.

Los servicios de seguridad ucranianos han retenido e interrogado a Kateryna muchas veces por su trabajo. «A los dos años de trabajar con los medios extranjeros, pasas a primer plano en los intereses de los servicios de seguridad», asegura. «Y es mejor no subestimar su poder. Son lo bastante astutos para jugar con tu vida».

Últimamente se siente expuesta en Donetsk y quiere encontrar un trabajo distinto. «En cuanto se marcha un equipo de televisión, ya está», añade. «Solo una vez he sentido que les importaba a los medios internacionales. El pasado mayo, un colega de la BBC me preguntó si necesitaba ayuda, ahora que habían publicado mi nombre en Myrotvorets. Rechacé cualquier tipo de apoyo; era lo mínimo que pudo haberme pasado».

Pocos guías llegan a recibir compensación si se lesionan o mueren realizando su trabajo. Tampoco reciben la protección internacional de facto que se proporciona a los corresponsales que trabajan en el exterior. Solo en Afganistán, docenas de traductores, conductores y productores locales perdieron la vida entre 2003 y 2011; algunos, muertos en enfrentamientos, otros —como Aymal Naqshbandi, periodista, y Sayed Aga, conductor— fueron ejecutados por los talibanes por haber trabajado con extranjeros

Saira, una guía de Kabul (Afganistán) que lleva nueve años en esto, solo puede trabajar si oculta no solo su identidad, sino también su propio cuerpo. Como mujer sufre amenazas y abusos constantes. Teme tanto ser castigada que no quiso darnos su nombre verdadero para este artículo. La joven de 26 años, que comenzó a trabajar con periodistas extranjeros para poder pagarse los estudios en la universidad de Kabul, dice que solo se siente a salvo con el rostro cubierto. «He viajado a algunos sitios peligrosos con periodistas extranjeros. Tuve que taparme la cara completamente con un burka para sentirme segura», explica.

«Para una mujer siempre es peligroso trabajar, incluso en Kabul. Eres blanco de comentarios hirientes y faltas de respeto. Mucha gente te culpa y llegan a llamarte infiel porque trabajas con gente no musulmana», añade Saira.

Cada vez se contrata a más guías que viven en zonas de conflicto consideradas demasiado peligrosas para los corresponsales extranjeros, y desde las cuales aquellos escriben y envían directamente las noticias a las redacciones internacionales. «Cada vez se depende más de periodistas independientes locales para conseguir noticias, artículos e imágenes en países y zonas a los que es muy difícil —o demasiado peligroso— que accedan [los reporteros internacionales]», explica Clarke. «No tenemos datos ni cifras exactas; nuestras pruebas son mayoritariamente anecdóticas y las obtenemos de lo que hemos visto y oído al realizar nuestra labor».

Almigdad Moyali era un guía que se convirtió en reportero cuando la guerra de Yemen forzó a muchos extranjeros a marcharse del país. Moyali, de 34 años, tenía buen nivel de inglés, conocía a la gente adecuada, tenía el respeto de la gente y estaba muy solicitado.

Prefería trabajar de forma anónima. «Le gustaba ser guía porque le permitía contar historias que en Yemen habría sido demasiado peligroso contar», relata Laura Battaglia, una periodista italiana que trabajaba con Moyali y entabló amistad con él. «Con su permiso omitimos su nombre en artículos difíciles, para protegerlo».

Pero cuando Moyali comenzó a cubrir noticias por su cuenta, esto lo metió en problemas con la milicia hutí, un grupo rebelde en control de Saná, la capital yemení. Prácticamente la primera de sus historias, que envió a redacciones europeas y estadounidenses firmadas con su nombre, le ganó la ira de la clase dirigente. Fue arrestado de inmediato y amenazado por agentes del gobierno. Perdió la vida en enero de este año, en un ataque aéreo en plena misión para Voice of America. Se encontraba viajando por una zona peligrosa en un coche sin marcar y sin nada que lo identificase como periodista.

La muerte de Moyali provoca preguntas acerca de la responsabilidad. Era autónomo, pero trabajaba para agencias de noticias internacionales. Mike Garrod, cofundador de World Fixer, una red digital que conecta a periodistas y trabajadores en sus países con reporteros internacionales, cree que algunos grupos de comunicación están comenzando a tomarse más en serio el papel que desempeñan en la protección de los trabajadores que contratan.

Garrod espera fundar un programa de formación en línea para periodistas y guías locales. El curso incluirá seguridad, evaluación de riesgos y estándares y ética periodística. «Los guías, en gran medida, carecen de formación y son vulnerables en entornos hostiles. A medida que se afianza la tendencia a utilizarlos para cosas que van mucho más allá de la traducción y la logística, existe una necesidad real de que entiendan ciertos conceptos y que demuestren que los entienden», expone Garrod. Para este artículo preguntamos a la BBC, la CNN y Reuters por sus guías. Todas se abstuvieron de comentar.

No obstante, el comportamiento de algunos periodistas individuales que emplean a guías en el campo es más complicado de regular, según Garrod. Nos contó la historia de un joven estudiante al que contrató un reportero extranjero para viajar al frente de la guerra de Irak cuando tenía 17 años. «La industria puede hacer muchísimo más para instar a los periodistas a que actúen de forma más responsable en lo concerniente a este asunto, pero me preocupa que no exista una voluntad de inspeccionar el modo en el que se consigue una noticia», lamenta.

Zia Ur Rehman, de 35 años, trabajó con corresponsales extranjeros en Karachi, Pakistán, entre 2011 y 2015. Cuenta que, mientras los periodistas de la ciudad entienden los peligros a los que se exponen allí, algunos reporteros extranjeros ignoran sus consejos. «Algunos cámaras y fotógrafos son groseros y maleducados, y tratan a sus guías como si fueran sus sirvientes. Como no conocen la complejidad y lo delicado de la situación, graban o sacan fotos sin consultar a su guía, cosa que ha acarreado problemas muy serios al equipo, sobre todo al guía», declara Rehman.

Ha habido casos en los que los servicios de seguridad pakistaníes han secuestrado a guías, que han sufrido palizas e incluso torturas por trabajar con periodistas extranjeros. Rehman dice que ya rara vez trabaja como guía; si lo hace, solo es para reporteros que ya conoce.

Más formación y el apoyo de las organizaciones internacionales que emplean a guías son dos elementos cruciales para su seguridad, pero es poco probable que suponga un gran cambio en áreas aún en control del Estado Islámico, decidido a silenciar a los periodistas, especialmente a los que trabajan con compañías extranjeras. En junio de este año, el CPJ denunció que el EI había ejecutado en Siria a cinco periodistas independientes. A uno lo ataron a su ordenador; a otro, a su cámara. Después los forraron de explosivos y los hicieron detonar. Habían sido acusados de trabajar con agencias extranjeras de noticias y de derechos humanos. El Estado Islámico publicó vídeos de la matanza a modo de advertencia para el resto.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Caroline Lees ha sido corresponsal en el sur de Asia para el periódico británico The Sunday Times. Actualmente es jefa de investigación en el Instituto Reuters para el Estudio del Periodismo en la Universidad de Oxford

*Algunos nombres de este artículo han sido modificados por motivos de seguridad

Este artículo fue publicado en la revista Index on Censorship en otoño de 2017

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

19 Dec 2017 | Journalism Toolbox Arabic

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”يعتمد الكثير من المراسلين الأجانب على “أدلّاء“ صحفيين (Fixers) لمساعدتهم على تغطية مناطق الصراع. ولكن، كما تكشف كارولين ليس، يتعرّض هؤلاء الأشخاص في أحيان كثيرة للاستهداف كـ“جواسيس“ عندما تكشف أسمائهم الحقيقية محليا”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

صحفيون أوكرانيون في مؤتمر صحفي عقد بالسفارة الأمريكية, US Embassy Kiev Ukraine/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

يخاطر رواند بحياته بشكل متكرّر من أجل أشخاص لا يعرفهم. فطالب علوم الكمبيوتر البالغ من العمر 25 عاما يعمل بشكل مواز كـ”دليل” صحفي محلّي يساعد المراسلين الأجانب، في أربيل بالعراق. تبعد المدينة مسافة ساعة واحدة فقط عن الموصل، التي يحتلّها تنظيم الدولة الإسلامية (داعش). كان التنظيم قد هدّد في شهر يونيو/حزيران بقتل الصحفيين الذين “يحاربون ضد الإسلام”.

يقول رواند الذي عمل سابقا مع مجلة “فيس نيوز” و “تايم”: “دعونا نتخيّل أن داعش أتت إلى أربيل، فأول الناس الذين سوف يبحثون عنهم هم الأدلّاء الصحفيون”. ويضيف “بعد كل تقرير فإن الدليل يبقى في البلاد، في حين أن لدى المراسل جواز سفر أجنبي ويمكنه أن يغادر” البلاد عندما يشاء.

ويقوم الأدلّاء بتوّلي الخدمات اللوجستية للمراسلين الأجانب، بما فيها الترجمة والتوجيه، ولكنهم يقومون أيضا بالبحث وجمع المصادر، وترتيب المقابلات، والذهاب إلى الخطوط الأمامية. معظمهم هم من العاملين لحسابهم الخاص، وهم معرّضون بشدّة للتهديدات والأعمال الانتقامية، خاصة عندما يغادر زملاؤهم الأجانب. فطبقا لمنظمة روري بيك تروست، وهي منظمة تدعم العاملين لحسابهم الخاص في جميع أنحاء العالم، فإن عدد الصحفيين المحليين المستقلين الذين يتم استهدافهم بسبب عملهم في مساعدة الإعلام الدولي قد ازداد بشكل كبير في الآونة الأخيرة.

تقول مولي كلارك، مديرة الاتصالات في روري بيك: “إن غالبية طلبات المساعدة تأتينا من الصحفيين المحليين المستقلين الذين يتعرضون للتهديد أو الاحتجاز أو السجن أو الاعتداء أوالإبعاد القسري بسبب عملهم”. وتضيف “نحن نقوم بشكل منتظم بدعم أولئك الذين يتم استهدافهم بسبب عملهم مع وسائل الإعلام الدولية. ففي هذه الحالات يمكن أن تكون العواقب مدمرة وطويلة الأجل – ليس فقط بالنسبة لهم ولكن لعائلاتهم أيضا “.

وتفيد لجنة حماية الصحفيين أن 94 “من العاملين في الإعلام” كانوا قد قتلوا منذ 2003، العام الذي بدأت فيه لجنة حماية الصحفيين بتصنيف الأدلّاء في خانة منفصلة تقديرا منها لأهميتهم المتزايدة في التقارير الإخبارية الأجنبية. وفي حزيران / يونيو من هذا العام، أضافة لجنة حماية الصحفيين زبي الله تامانا، وهو صحفي أفغاني مستقلّ يعمل كمترجم لإذاعة إن.بي.أر في الولايات المتحدة، إلى قائمة أولئك الذين قتلوا في تفجير استهدف قافلة كان يتنقّل معها في أفغانستان

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

یبدأ العدید من الأدلّاء مسيرتهم كهواة قليلي الخبرة ویائسين للحصول على عمل مدفوع الأجر، عادة في دول ذات اقتصادات متضرّرة بسبب الحرب. وهم نادرا ما يحصلون على تدريب أو دعم طويل الأجل من قبل المنظمات الدولية التي يعملون من أجلها، وغالبا ما يكونون مسؤولين بأنفسهم عن سلامتهم الشخصية. تعلّم رواند أن يخفي هويته في أربيل ونادرا ما يضع اسمه في تقرير أو مادة يساهم فيها. “إن إرفاق اسمي بالتقارير يعني أنني لست مجهول الهوية. قد يؤدّي ذلك الى شكوك حولي وقد أعامل كجاسوس “.

تلقّي الاتهامات بالتجسس يشكل خطرا مهنيا بالنسبة للعديد من الأدلّاء الذين يعملون مع الصحفيين الأجانب. بالنسبة لأولئك الذين يعملون على الجبهة بين أوكرانيا والانفصاليين المدعومين من روسيا، مثلا، يشكّل هذا الاتهام تهديدا يوميا. ففي عام 2014، اختطف انطون سكيبا، وهو منتج محلي من دونيتسك، من قبل الانفصاليين واتهم بأنه جاسوس أوكراني. وكان قد قضى اليوم فى العمل لصالح شبكة سي ان ان في الموقع الذى تحطمت فيه طائرة تابعة للخطوط الجوية الماليزية رحلة MH17 في شرق اوكرانيا التي يسيطر عليها الانفصاليون. وقد أطلق سراح سكيبا، الذي عمل أيضا مع هيئة الإذاعة البريطانية، في نهاية المطاف، بعد حملة قام بها زملاؤه. وقال “من المهم حقا ان نبقى متوازنين عندما يكون لدينا القدرة الى الوصول الى كلا الجانبين، والا فان هناك احتمال كبير ان يتم قمعنا من قبل احد الطرفين”.

يحاول سكيبا حماية نفسه من خلال الحرص على الناس الذين يعمل معهم والمواضيع التي يغطّيها. يقول “هذا بلدي حيث سوف أستمر بالعيش هنا بعد أن ينتقل الصحفيون إلى تغطية صراع آخر. لا أريد المخاطرة بحياتي من أجل موضوع قد يتم نسيانه في اليوم التالي. لهذا السبب، أحاول تجنّب الصحفيين غير المحترفين والذين يستغلّون الأدلّاء الوصول الى المواضيع “الساخنة”.”

أما كاترينا، وهي دليل آخر من منطقة دونيتسك، فقد حصلت على اعتماد صحفي من كل من السلطات الأوكرانية وجمهورية دونيتسك الشعبية الانفصالية لتجنب الاتهامات بتفضيل طرف واحد على الأخر. ولكن هذا لم يوقف التهديدات والمضايقات ضدها. ففيما لا تعلن كاترينا أنها تعمل مع صحفيين دوليين، قام موقع أوكرانيا على شبكة الإنترنت، وهو “ميروفيتورس”، قام مؤخرا بالكشف عن أسماء وعناوين بريد إلكتروني وأرقام هواتف حوالي 5000 صحفي أجنبي ومحلي عملوا في وجمهورية دونيتسك الشعبية وفي لوهانسك – وهي مناطق انفصالية لا تسيطر عليها الحكومة الأوكرانية. ظهر اسم كاترينا، 28 عاما، عدة مرات في هذه القائمة، التي نشرت في مايو 2016، لأنها عملت مع بي بي سي، وشبكة الجزيرة ووسائل إعلام أخرى.

وقد تم احتجاز كاترينا عدّة مرّات واستجوابها من قبل أجهزة الأمن الأوكرانية بسبب عملها. تقول “بعد عامين من العمل مع وسائل الاعلام الاجنبية أصبحت في دائرة الضوء الامنية”. وتضيف “من الأفضل عدم الاستهانة بقوتهم. فهم أذكياء بما فيه الكفاية للتلاعب بحياتك.”

تقول كاترينا انها تشعر الآن بأنها معرّضة للخطر في دونيتسك وترغب في الانتقال الى عمل آخر. تقول: “بمجرد مغادرة طاقم التلفزيون، ينتهي كل شيء…مرة واحدة فقط شعرت بالاهتمام من قبل وسائل الإعلام الدولية. ففي مايو / أيار، سألني أحد زملائي في هيئة الإذاعة البريطانية عما إذا كنت بحاجة إلى الدعم بعد نشر اسمي على ميرتفوريتس. رفضت أي مساعدة لأن نشر اسمي كان أقل ما يمكن أن يحدث لي”.

هناك عدد قليل جدا من الأدلّاء الصحفيين مؤهلين للحصول على تعويضات إذا ما أصيبوا أو قتلوا أثناء العمل. كما أنهم لا يتمتعون بالحماية الدولية التي تمنح عمليا إلى الصحفيين الأجانب العاملين في الخارج. في أفغانستان وحدها، قتل عشرات المترجمين والسائقين والمنتجين المحليين بين عامي 2003 و 2011، بعضهم في ساحات القتال، وآخرين، مثل الصحفي أجمل نقشبندي والسائق سيد آغا، أعدمتهم جماعة طالبان بتهمة العمل مع أجانب.

بدورها، فإن سايرة، وهي دليل صحفي عملت في كابول بأفغانستان خلال السنوات التسع الماضية، لا تستطيع أن تعمل إلا إذا أخفت ليس فقط هويتها، بل نفسها أيضا. كامرأة فهي تتعرض باستمرار للتهديد وإساءة المعاملة. وبدت خائفة جدا من الانتقام لو أعطت اسمها الحقيقي من أجل هذا التقرير. وقالت الامرأة البالغة من العمر 26 عاما، التي كانت قد بدأت بالعمل مع الصحفيين الاجانب للمساعدة في تمويل دراستها في جامعة كابول، قالت انها تشعر فقط بالأمان عندما يكون وجهها منقّب. “لقد سافرت إلى بعض الأماكن الخطرة مع الصحفيين الأجانب. كان علي أن أغطى وجهي بالبرقع لكي أشعر بالأمان”. وتضيف: “هناك دائما أخطارا على المرأة التي تعمل، حتى في كابول، فإنها قد تتلقى تعليقات مسيئة من المجتمع وتقفد الاحترام. كثير من الناس يلومونك وحتى يتهمّوك بالكفر اذا كنت تعمل مع شخص غير مسلم”.

لقد ازدادت ظاهرة توظيف الأدلاء الصحفيين في المناطق التي تعتبر خطرة جدا بالنسبة للمراسلين الأجانب، لكتابة وإرسال التقارير مباشرة الى وسائل الإعلام الدولية. وتقول كلارك: “هناك اعتماد متزايد على العاملين لحسابهم الخاص في مجال الأخبار والصور في البلدان والمناطق الخطرة أو تلك التي يكون من الصعب [للمراسلين الدوليين] الوصول إليها. وتضيف “ليس لدينا أي حقائق أو أرقام محددة، فإن أدلتنا في الغالب تأتي من ما نسمعه ونلاحظه من خلال عملنا”.

كان المقداد مجلي يعمل دليلا صحفيا ثم أصبح مراسلا عندما أجبرت الحرب في اليمن العديد من الأجانب على مغادرة البلاد. كان مجلي، 34 عاما، يتحدث الإنجليزية جيّدا، ولديه علاقات واسعة، وتمتّع بالاحترام وكان هناك طلب كبير على خدماته. فضل مجلي العمل دون الكشف عن هويته. تقول لورا باتاغليا، الصحفية الإيطالية التي عملت معه وأصبحت صديقة له فيما بعد: “كان يحب العمل كدليل صحفي لأن ذلك سمح له بإخبار القصص التي لا يستطيع أن يرويها بأمان في اليمن”. وتضيف: “بالاتفاق معه، كنا نخفي اسمه من المقالات الصعبة لحمايته”.

ولكن عندما بدأ مجلي في تغطية الأخبار بمفرده، واجه مشاكل مع ميليشيا الحوثيين، وهي جماعة متمرّدة تسيطر على صنعاء، عاصمة اليمن. أغضبت مقالته الأولى التي أرسلها الى الصحف الإخبارية في أوروبا والولايات المتحدة تحت اسمه الجهات الحاكمة فورا، فألقي القبض عليه وتم تهديده من قبل عملاء الحكومة. وفي كانون الثاني / يناير من هذا العام، قتل في غارة جوية أثناء تغطيته الأحداث لإذاعة فويس أوف أمريكا. كان يتنقّل في منطقة خطرة في سيارة لا تحمل ايّ علامات تشير إلى أنه صحفي.

أثار مصرع مجلي أسئلة تتعلق بتوزيع المسؤولية. فعلى الرغم من أنه كان يعمل على حسابه الخاص، كان عمله في النهاية يصبّ في مجال المنظمات الإعلامية الدولية. يعتقد مايك غارود، المؤسس المشارك لـ”وورد فيكسر”، وهي شبكة على الانترنت تربط الصحفيين المحليين والمستقلّين مع المراسلين الدوليين، أن بعض الجماعات الإعلامية بدأت تلعب دورها بجديّة أكبر لضمان سلامة العاملين لحسابهم الخاص الذين تتعامل معهم.

يخطّط غارود لإعداد برنامج تدريبي عبر الإنترنت للصحفيين والأدلّاء المحليين. وستشمل الدورة تقييم المخاطر، والأمن، والمعايير الصحفية والأخلاقيات. يقول “الأدلّاء هم إلى حد كبير غير مدرّبون وهم معرّضون للخطر في البيئات المعادية. وبما أن خدمات الأدلّاء قد توّسعت خارج نطاق الترجمة والخدمات “فهناك حاجة حقيقية لأن يفهموا ويدركوا مفاهيم معينة”، يضيف غارود. وقد سئلنا شبكات بي بي سي و سي إن إن ورويترز عن سياساتهم الخاصة حول استخدام الأدلّاء ولكنهم رفضوا الادلاء بأي تعليق.

بحسب غارود، فإن تنظيم سلوك الصحفيين الذين يستخدمون الأدلّاء في الحقل يبقى صعبا. ويذكر هنا قصة طالب شاب، استأجره مراسل أجنبي للذهاب إلى خط الجبهة في العراق عندما كان عمره 17 عاما. “هناك الكثير مما يمكن أن يفعله القطاع لتشجيع الصحفيين على التصرف بشكل أكثر مسؤولية فيما يتعلق بهذه المسألة، ولكن ما يقلقني هو غياب الإرادة للتدقيق في الكيفية التي يتم بها جمع المعلومات من أجل التقارير”.

من جهته، عمل ضياء الرحمن ، 35 عاما، مع مراسلين أجانب في كراتشي، باكستان، بين عامي 2011 و 2015. ويقول أنه بخلاف الصحفيين المحليين في المدينة الذين يفهمون المخاطر التي تواجه الصحفيين هناك، فهناك بعض الصحفيين الأجانب الذين يتجاهلون نصيحتهم. يقول “بعض المصورين لديهم طباع سيئة وهم وقحون ويعاملون الأدلّاء كأنهم خدم. بما انهم لا يعرفون تعقيدات وحساسية الوضع، فهم يقومون بتصوير افلام أو التقاط الصور دون استشارة الأدلّاء، مما تسبب بمشاكل كبيرة للفريق، لا سيما للأدلاء”.

في بعض الحالات، اختطف أدلّاء وضربوا وتعرّضوا للتعذيب على أيدي أجهزة الأمن الباكستانية بسبب عملهم مع صحفيين أجانب. وقال رحمن انه نادرا ما يعمل كدليل صحفي الآن، ولا يتعامل الا مع مراسلين يعرفهم عن كثب.

انه من الضروري أن يتم تقديم المزيد من التدريب والدعم من قبل المنظمات الدولية التي تستخدم الأدلّاء من أجل سلامتهم، ولكنه يظل من غير المرجح أن يحدث هذا فرقا في المناطق التي ما زال يسيطر عليها تنظيم داعش، الذي يصمم على إسكات الصحفيين، خاصة أولئك الذين يعملون مع المؤسسات الأجنبية. في يونيو/حزيران من هذا العام، ذكرت لجنة حماية الصحفيين أن تنظيم الدولة الإسلامية أعدم خمسا من الصحفيين المستقلين في سوريا. تم ربط احدهم بجهاز الكمبيوتر المحمول الخاص به، وآخر إلى كاميرته، بعد أن تم تفخيخهما ثم فجرّت بهم. وقد اتهموا بالعمل مع مؤسسات الأخبار ومنظمات حقوق الإنسان الأجنبية. نشرت داعش تسجيلا للإعدام لكي يكوم أمثولة وتحذيرا للآخرين.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

)تم تغيير بعض الأسماء في هذه المقالة لأسباب أمنية (

كارولين ليز مراسلة سابقة لصحيفة صنداي تايمز البريطانية في جنوب آسيا. وتعمل حاليا كباحثة مع معهد رويترز لدراسة الصحافة في جامعة أكسفورد

*ظهر هذا المقال أولا في مجلّة “اندكس أون سنسورشيب” بتاريخ ٢٠ سبتمبر/أيلول ٢٠١٦

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Jun 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The truth is in danger. Working with reporters and writers around the world, Index continually hears first-hand stories of the pressures of reporting, and of how journalists are too afraid to write or broadcast because of what might happen next.

In 2016 journalists are high-profile targets. They are no longer the gatekeepers to media coverage and the consequences have been terrible. Their security has been stripped away. Factions such as the Taliban and IS have found their own ways to push out their news, creating and publishing their own “stories” on blogs, YouTube and other social media. They no longer have to speak to journalists to tell their stories to a wider public. This has weakened journalists’ “value”, and the need to protect them. In this our 250th issue, we remember the threats writers faced when our magazine was set up in 1972 and hear from our reporters around the world who have some incredible and frightened stories to tell about pressures on them today.

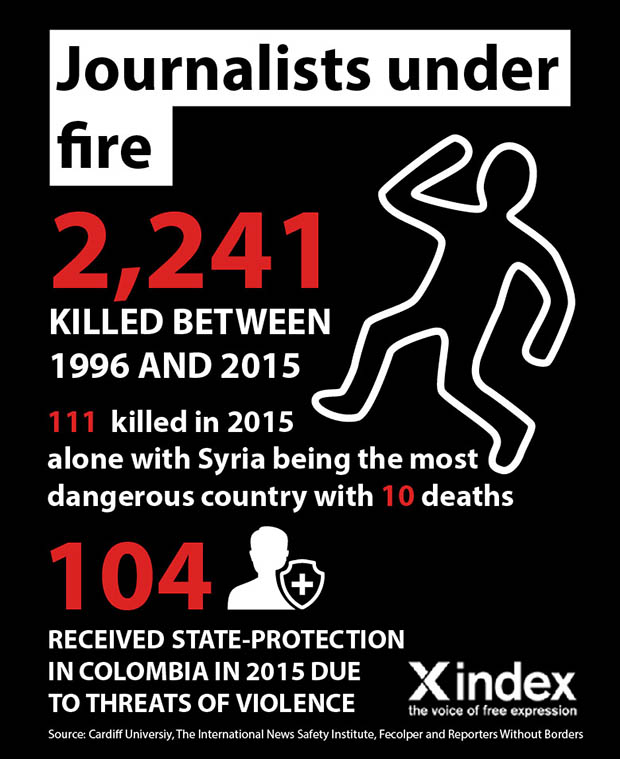

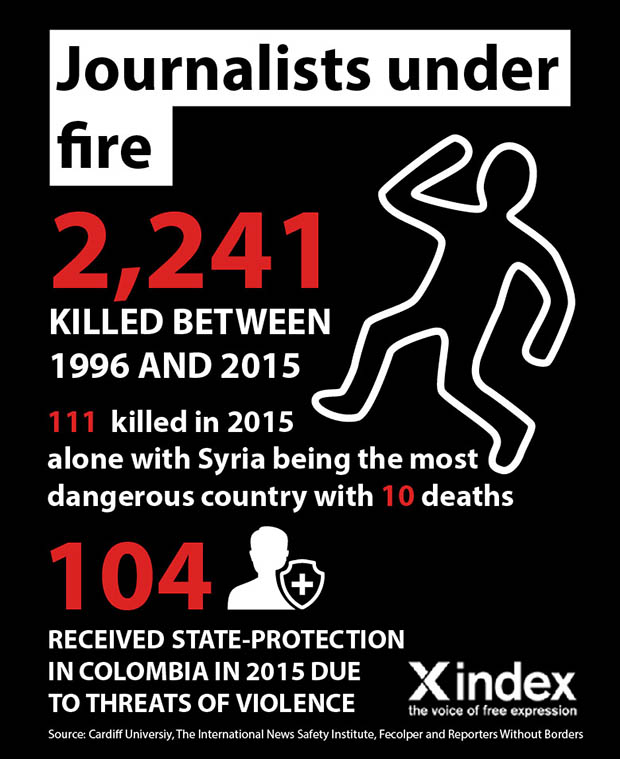

Around 2,241 journalists were killed between 1996 and 2015, according to statistics compiled by Cardiff University and the International News Safety Institute. And in Colombia during 2015 104 journalists were receiving state protection, after being threatened.

In Yemen, considered by the Committee to Protect Journalists to be one of the deadliest countries to report from, only the extremely brave dare to report. And that number is dwindling fast. Our contacts tell us that the pressure on local journalists not to do their job is incredible. Journalists are kidnapped and released at will. Reporters for independent media are monitored. Printed publications have closed down. And most recently 10 journalists were arrested by Houthi militias. In that environment what price the news? The price that many journalists pay is their lives or their freedom. And not just in Yemen.

Syria, Mexico, Colombia, Afghanistan and Iraq, all appear in the top 10 of league tables for danger to journalists. In just the last few weeks National Public Radio’s photojournalist David Gilkey and colleague Zabihullah Tamanna were killed in Afghanistan as they went about their work in collecting information, and researching stories to tell the public what is happening in that war-blasted nation. One of our writers for this issue was a foreign correspondent in Afghanistan in 1990s and remembers how different it was then. Reporters could walk down the street and meet with the Taliban without fearing for their lives. Those days have gone. Christina Lamb, from London’s Sunday Times, tells Index, that it can even be difficult to be seen in a public place now. She was recently asked to move on from a coffee shop because the owners were worried she was drawing attention to the premises just by being there.

Physical violence is not the only way the news is being suppressed. In Eritrea, journalists are being silenced by pressure from one of the most secretive governments in the world. Those that work for state media do so with the knowledge that if they take a step wrong, and write a story that the government doesn’t like, they could be arrested or tortured.

In many countries around the world, journalists have lost their status as observers and now come under direct attack. In the not-too-distant past journalists would be on frontlines, able to report on what was happening, without being directly targeted.

So despite what others have described as “the blizzard of news media” in the world, it is becoming frighteningly difficult to find out what is happening in places where those in power would rather you didn’t know. Governments and armed groups are becoming more sophisticated at manipulating public attitudes, using all the modern conveniences of a connected world. Governments not only try to control journalists, but sometimes do everything to discredit them.

As George Orwell said: “In times of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” Telling the truth is now being viewed by the powerful as a form of protest and rebellion against their strength.

We are living in a historical moment where leaders and their followers see the freedom to report as something that should be smothered, and asphyxiated, held down until it dies.

What we have seen in Syria is a deliberate stifling of news, making conditions impossibly dangerous for international media to cover, making local news media fear for their lives if they cover stories that make some powerful people uncomfortable. The bravest of the brave carry on against all the odds. But the forces against them are ruthless.

As Simon Cottle, Richard Sambrook and Nick Mosdell write in their upcoming book, Reporting Dangerously: Journalist Killings, Intimidation and Security: “The killing of journalists is clearly not only to shock but also to intimidate. As such it has become an effective way for groups and even governments to reduce scrutiny and accountability, and establish the space to pursue non-democratic means.”

In Turkey we are seeing the systematic crushing of the press by a government which appears to hate anyone who says anything it disagrees with, or reports on issues that it would rather were ignored. Journalists are under pressure, and so is the truth.

As our Turkey contributing editor Kaya Genç reports on page 64, many of Turkey’s most respected news outlets are closing down or being forced out of business. Secrets are no longer being aired and criticism is out of fashion. But mobs attacking newspaper buildings is not. Genç also believes that society is shifting and the public is being persuaded that they must pick sides, and that somehow media that publish stories they disagree with should not have a future.

That is not a future we would wish upon the world.

Order your full-colour print copy of our journalism in danger magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London, Home in Manchester, Carlton Books in Glasgow and News from Nowhere in Liverpool as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94291″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533353″][vc_custom_heading text=”Afghanistan in 1978-81″ font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533353|||”][vc_column_text]April 1982

Anthony Hyman looks at the changing fortunes of Afghan intellectuals over the past four or five years.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94251″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533410″][vc_custom_heading text=”Colombia: a new beginning?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533410|||”][vc_column_text]August 1982

Gabriel García Márquez and others who faced brutal government repression following the 1982 election.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93979″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533703″][vc_custom_heading text=”Repression in Iraq and Syria” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533703|||”][vc_column_text]April 1983

An anonymous report from Amnesty point to torture, special courts and hundreds of executions in Iraq and Syria. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Danger in truth: truth in danger” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F05%2Fdanger-in-truth-truth-in-danger%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at why journalists around the world face increasing threats.

In the issue: articles by journalists Lindsey Hilsum and Jean-Paul Marthoz plus Stephen Grey. Special report on dangerous journalism, China’s most famous political cartoonist and the late Henning Mankell on colonialism in Africa.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”76282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/05/danger-in-truth-truth-in-danger/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]