Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]We, the undersigned 53 international and Russian human rights, media and Internet freedom organisations, strongly condemn the attempts by the Russian Federation to block the internet messaging service Telegram, which have resulted in extensive violations of freedom of expression and access to information, including mass collateral website blocking.

We call on Russia to stop blocking Telegram and cease its relentless attacks on internet freedom more broadly. We also call the United Nations (UN), the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the European Union (EU), the United States and other concerned governments to challenge Russia’s actions and uphold the fundamental rights to freedom of expression and privacy online as well as offline. Lastly, we call on internet companies to resist unfounded and extra-legal orders that violate their users’ rights.

Massive internet disruptions

On 13 April 2018, Moscow’s Tagansky District Court granted Roskomnadzor, Russia’s communications regulator, its request to block access to Telegram on the grounds that the company had not complied with a 2017 order to provide decryption keys to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). Since then, the actions taken by the Russian authorities to restrict access to Telegram have caused mass internet disruption, including:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-file-excel-o” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Background on restrictive internet laws

Over the past six years, Russia has adopted a huge raft of laws restricting freedom of expression and the right to privacy online. These include the creation in 2012 of a blacklist of internet websites, managed by Roskomnadzor, and the incremental extension of the grounds upon which websites can be blocked, including without a court order.

The 2016 so-called ‘Yarovaya Law’, justified on the grounds of “countering extremism”, requires all communications providers and internet operators to store metadata about their users’ communications activities, to disclose decryption keys at the security services’ request, and to use only encryption methods approved by the Russian government – in practical terms, to create a backdoor for Russia’s security agents to access internet users’ data, traffic, and communications.

In October 2017, a magistrate found Telegram guilty of an administrative offense for failing to provide decryption keys to the Russian authorities – which the company states it cannot do due to Telegram’s use of end-to-end encryption. The company was fined 800,000 rubles (approx. 11,000 EUR). Telegram lost an appeal against the administrative charge in March 2018, giving the Russian authorities formal grounds to block Telegram in Russia, under Article 15.4 of the Federal Law “On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection”.

The Russian authorities’ latest move against Telegram demonstrates the serious implications for people’s freedom of expression and right to privacy online in Russia and worldwide:

Such attempts by the Russian authorities to control online communications and invade privacy go far beyond what can be considered necessary and proportionate to countering terrorism and violate international law.

International Standards

We, the undersigned organisations, call on:

Signed by

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1526459542623-9472d6b1-41e3-0″ taxonomies=”15″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”100082″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]

Понедельник, 30 апреля 2018 г.

Мы, нижеподписавшиеся 26 международных правозащитных организации в сфере медиа и интернет-свобод, решительно осуждаем попытки Российской Федерации заблокировать интернет-мессенджер Telegram, результатом которых стали широкомасштабные нарушения свободы выражения мнения и доступа к информации, и в т.ч. массовая блокировка сторонних вебсайтов.

Мы призываем Россию остановить блокировку Telegram и прекратить беспрестанные нападки на свободу интернета в целом. Мы также призываем Организацию Объединенных Наций, Совет Европы, Организацию по безопасности и сотрудничеству в Европе, Европейский Союз, Соединенные Штаты Америки и другие заинтересованные правительства оспорить действия России и поддержать основополагающие права на свободу выражения мнения и неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете и вне его. Наконец, мы призываем интернет-компании противостоять необоснованным и неправовым требованиям, нарушающим права их пользователей.

Массовые перебои в работе интернета

13 апреля 2018 г. Таганский районный суд Москвы удовлетворил запрос Роскомнадзора о блокировке доступа к Telegram на основании того, что компания не исполнила датированное 2017 годом распоряжение передать ключи шифрования Федеральной службе безопасности (ФСБ). С того времени действия, предпринятые российскими органами власти с целью ограничить доступ к Telegram, привели к массовым перебоям в работе интернета, в т.ч.:

16-18 апреля 2018 года Роскомнадзор отдал указание о блокировке почти 20 миллионов IP-адресов в попытке ограничить доступ к Telegram. Значительная часть заблокированных адресов принадлежит международным интернет-компаниям, в т.ч. Google, Amazon и Microsoft. В настоящее время XX из них остаются заблокированными.

Массовая блокировка IP-адресов негативно влияет на большое число сетевых сервисов, которые не имеют никакого отношения к Telegram, в числе прочего интернет-банкинг и сайты бронирования гостиниц, электронная коммерция и покупка авиабилетов.

Международная правозащитная группа Агора, представляющая Telegram в России, сообщила, что были получены запросы о помощи в связи с массовыми блокировками от около 60 компаний, включая интернет-магазины, службы доставки и разработчиков программного обеспечения.

По меньшей мере шесть интернет-СМИ (Петербургский дневник, Coda Story, FlashNord, FlashSiberia, Тайга.инфо, и 7×7) пострадали от временного ограничения доступа к их вебсайтам.

17 апреля 2018 года Роскомнадзор потребовал от Google и Apple удалить приложение Telegram из магазинов приложений, несмотря на отсутствие в российском законодательстве оснований для такого требования. Приложение на данный момент остается доступным, однако Telegram не может предоставить обновление для улучшения доступа через прокси-серверы.

Провайдеры виртуальных частных сетей (VPN), такие как TgVPN, Le VPN и VeeSecurity, также были заблокированы из-за предоставления альтернативных средств доступа к Telegram. Федеральный закон 276-ФЗ запрещает использование VPN и интернет-анонимайзеров для предоставления доступа к вебсайтам, заблокированным в России, и дает полномочия Роскомнадзору по блокировке любого сайта, объясняющего, как пользоваться такими сервисами.

История ограничительного законодательного регулирования интернета

В течение последних шести лет Россия приняла большое число законов, ограничивающих свободу выражения мнения и право на неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете. В их число входит создание в 2012 г. черного списка интернет-сайтов, администрируемого Роскомнадзором, и поэтапное расширение оснований для блокировки вебсайтов, включая блокировку без решения суда.

Принятый в 2016 году т.н. «закон Яровой», нацеленный на «борьбу с экстремизмом», налагает обязательства на всех операторов связи и интернет-провайдеров хранить метаданные пользователей, предоставлять ключи шифрования по запросу органов безопасности и использовать исключительно методы шифрования, одобренные российским правительством, на практике это означает создание «бэкдора» для сотрудников российских органов безопасности для доступа к данным, трафику и коммуникациями интернет-пользователей.

В октябре 2017 года мировой судья признал Telegram виновным в совершении административного правонарушения в связи с непредоставлением ключей шифрования российским властям, что, по заявлению компании, невозможно сделать в силу использования Telegram сквозного шифрования. На компанию был наложен штраф в размере 800 000 рублей. Апелляция Telegram по административному делу была отклонена в марте 2018 года, что дало российским органам власти формальные основания для блокировки Telegram в России в соответствии со статьей 15.4 Федерального закона «Об информации, информационных технологиях и о защите информации».

Недавние меры, принятые российскими органами власти в отношении Telegram, имеют серьезные последствия для свободы выражения мнения и права на неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете в России и по всему миру:

Для российских пользователей такие приложения, как Telegram и другие подобные сервисы, стремящиеся предоставить защищенную связь, критически важны для обеспечения безопасности. Они представляют собой важный источник информации о важнейших проблемах политической, экономической и общественной жизни, свободный от неоправданного вмешательства правительства. Для СМИ и журналистов в России и за ее пределами Telegram служит не только платформой для обмена сообщениями с целью безопасного общения с источниками, но и площадкой для публикаций. Telegram-каналы представляют собой средство передачи и распространения контента для СМИ и отдельных журналистов и блогеров. С учетом прямого и косвенного контроля со стороны государства в отношении многих традиционных российских СМИ и самоцензуры, которую многие другие СМИ считают необходимым применять, каналы мгновенного обмена сообщениями, такие как Telegram, стали ключевым средством распространения идей и мнений.

Компании, которые исполняют требования «закона Яровой», предоставляя правительствам «бэкдор» к своим сервисам, ставят под угрозу безопасность сетевых коммуникаций как своих российских пользователей, так и людей, с которыми они общаются за пределами страны. Журналисты особенно опасаются, что предоставление ФСБ доступа к данной информации поставит под угрозу их источники – краеугольный камень свободы печати. Исполнение компаниями требований закона также означает, что поставщики услуг связи готовы понижать стандарты шифрования и подвергать риску личную информацию и безопасность всех своих пользователей в качестве одной из издержек ведения бизнеса.

В июле 2018 года вступят в силу статьи «закона Яровой», требующие, чтобы компании хранили все голосовые и текстовые сообщения в течение шести месяцев и открывали к ним доступ органам безопасности в отсутствие решения суда. Это повлияет на общение людей в России и за ее границами.

Такие попытки российских органов власти контролировать сетевые коммуникации и ограничивать неприкосновенность частной жизни выходят далеко за границы необходимости и соразмерности в рамках борьбы с терроризмом и нарушают международное законодательство.

Международные стандарты

Блокировка вебсайтов или приложений представляет собой крайнюю меру, аналогичную запрету газеты или отзыву лицензии у телевизионной станции. Как таковая она с большой вероятностью в подавляющем большинстве случаев представляет собой несоразмерное вмешательство в свободу выражения мнения и свободу СМИ и должна подлежать строгому контролю. Любые меры по блокировке по меньшей мере должны быть четко сформулированы в рамках закона и требовать рассмотрения судом того, является ли полная блокировка доступа к онлайн-сервису необходимой и соответствует ли критериям, установленным и применяемым Европейским судом по правам человека. Блокировка Telegram и связанные с ней действия очевидным образом не соответствуют данному стандарту.

Различные требования «закона Яровой» явно противоречат международным стандартам в отношении шифрования и анонимности в соответствии с Докладом Специального докладчика по вопросу о поощрении и защите права на свободу мнений и их свободное выражение 2015 года (A/HRC/29/32). Специальный докладчик ООН лично обратился к российскому правительству, выразив серьезное беспокойство, относительно чрезмерных ограничений, налагаемых «законом Яровой» на права на свободу выражения мнения и на неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете. Европейский суд постановил, что подобные обязательства по хранению данных являются несовместимыми с Хартией Европейского Союза по правам человека. Хотя Европейский суд по правам человека пока не принял решение относительно совместимости положений российского законодательства о раскрытии ключей шифрования с Конвенцией о защите прав человека и основных свобод, он постановил, что российский правовой режим, регулирующий перехват сообщений, не обеспечивает адекватные и эффективные гарантии против произвола и риска злоупотреблений, присущих системе секретной слежки.

Мы, нижеподписавшиеся организации призываем:

Российские органы власти гарантировать интернет-пользователям право публиковать и читать информацию в интернете анонимно и обеспечить, чтобы любые ограничения анонимности в интернете производились по распоряжению суда и полностью соответствовали требованиям Статей 17 и 19(3) Международного пакта о гражданских и политических правах и Статей 8 и 10 Конвенции о защите прав человека и основных свобод, путем:

Отказа от блокировки Telegram и воздержания от истребования у сервисов обмена сообщениями, таких как Telegram, ключей шифрования с целью получения доступа к частной информации пользователей;

Отмены положений «закона Яровой», налагающих на интернет-провайдеров обязательство хранить все телекоммуникационные данные сроком до шести месяцев и требующих обязательного обеспечения «бэкдоров» шифрования, а также закона 2014 года о локализации персональных данных, предоставляющего органам безопасности легкий доступ к данным пользователей без достаточных мер защиты.

Отмены Федерального закона 241-ФЗ, запрещающего анонимность пользователей интернет-мессенджеров, и Закона 276-ФЗ, запрещающего VPN-сервисам и интернет-анонимайзерам предоставлять доступ к вебсайтам, запрещенным в России;

Внесения изменений в Федеральный закон 149-ФЗ «Об информации, информационных технологиях и о защите информации» с тем, чтобы процесс блокировки вебсайтов соответствовал международным стандартом. Всякое решение о блокировке доступа к вебсайту или приложению должно быть принято независимым судом и ограничено требованием необходимости и соразмерности законной цели. При рассмотрении запроса на блокировку суд или другой независимый судебный орган, в чьи полномочия входит принятие такого решения, должен рассмотреть его влияние на законный контент и возможность использования технологических средств для предотвращения излишней блокировки.

Представителей Организации Объединенных Наций, Совета Европы, Организации по безопасности и сотрудничеству в Европе, Европейского Союза, Соединенных Штатов Америки и других заинтересованных правительств внимательно рассмотреть и открыто оспорить действия России с целью защиты основополагающих прав на свободу выражения мнения и неприкосновенность частной жизни в интернете и вне его, в соответствии с соглашениями, имеющими обязательную юридическую силу, стороной которых является Россия.

Интернет-компании противостоять требованиям, нарушающим международное право в области прав человека. Компании должны следовать Руководящим принципам предпринимательской деятельности в аспекте прав человека Организации Объединенных Наций, которые подчеркивают обязательство соблюдать права человека, применимое в рамках всей глобальной деятельности компании вне зависимости от места нахождения ее пользователей и исполнения государством своих обязательств в области защиты прав человека.

Подписи

ARTICLE 19

Международная Агора (Agora International)

Access Now

Amnesty International

Asociatia pentru Tehnologie si Internet – ApTI

Associação D3 – Defesa dos Direitos Digitais

Committee to Protect Journalists

Civil Rights Defenders

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Electronic Frontier Norway

Electronic Privacy Information Centre (EPIC)

Freedom House

Human Rights House Foundation

Human Rights Watch

Index on Censorship

International Media Support

Международное Партнерство за Права Человека (International Partnership for Human Rights)

ISOC Bulgaria

Open Media

Open Rights Group

ПЕН Америка (PEN America)

PEN International

Privacy International

Репортеры без границ (Reporters without Borders)

WWW Foundation

Xnet

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

We, the undersigned 26 international human rights, media and internet freedom organisations, strongly condemn the attempts by the Russian Federation to block the internet messaging service Telegram, which have resulted in extensive violations of freedom of expression and access to information, including mass collateral website blocking.

We call on Russia to stop blocking Telegram and cease its relentless attacks on internet freedom more broadly. We also call the United Nations (UN), the Council of Europe (CoE), the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the European Union (EU), the United States and other concerned governments to challenge Russia’s actions and uphold the fundamental rights to freedom of expression and privacy online as well as offline. Lastly, we call on internet companies to resist unfounded and extra-legal orders that violate their users’ rights.

On 13 April 2018, Moscow’s Tagansky District Court granted Roskomnadzor, Russia’s communications regulator, its request to block access to Telegram on the grounds that the company had not complied with a 2017 order to provide decryption keys to the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). Since then, the actions taken by the Russian authorities to restrict access to Telegram have caused mass internet disruption, including:

Over the past six years, Russia has adopted a huge raft of laws restricting freedom of expression and the right to privacy online. These include the creation in 2012 of a blacklist of internet websites, managed by Roskomnadzor, and the incremental extension of the grounds upon which websites can be blocked, including without a court order.

The 2016 so-called ‘Yarovaya Law’, justified on the grounds of “countering extremism”, requires all communications providers and internet operators to store metadata about their users’ communications activities, to disclose decryption keys at the security services’ request, and to use only encryption methods approved by the Russian government – in practical terms, to create a backdoor for Russia’s security agents to access internet users’ data, traffic, and communications.

In October 2017, a magistrate found Telegram guilty of an administrative offense for failing to provide decryption keys to the Russian authorities – which the company states it cannot do due to Telegram’s use of end-to-end encryption. The company was fined 800,000 rubles (approx. 11,000 EUR). Telegram lost an appeal against the administrative charge in March 2018, giving the Russian authorities formal grounds to block Telegram in Russia, under Article 15.4 of the Federal Law “On Information, Information Technologies and Information Protection”.

The Russian authorities’ latest move against Telegram demonstrates the serious implications for people’s freedom of expression and right to privacy online in Russia and worldwide:

Such attempts by the Russian authorities to control online communications and invade privacy go far beyond what can be considered necessary and proportionate to countering terrorism and violate international law.

Signed by

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1525093456273-1d231ece-6e3f-8″ taxonomies=”15″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

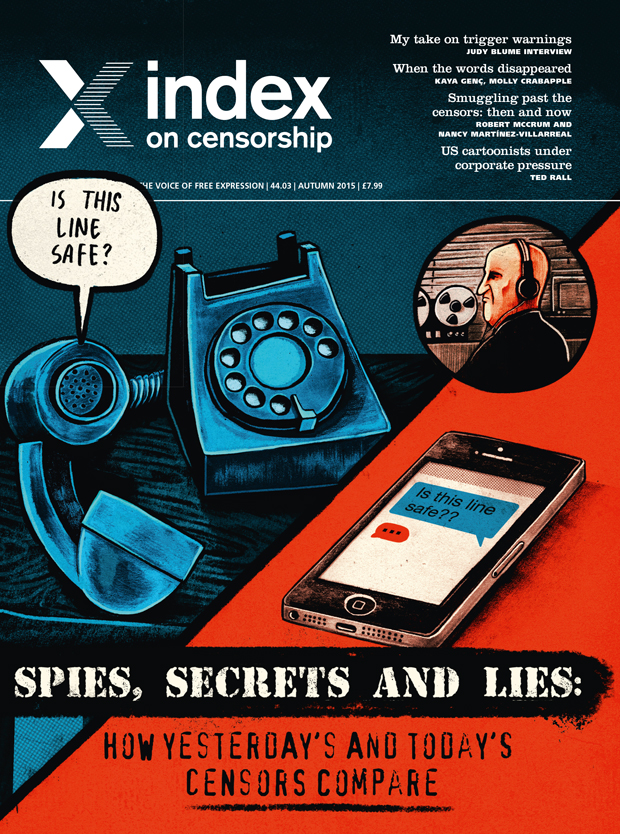

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

In the old days governments kept tabs on “intellectuals”, “subversives”, “enemies of the state” and others they didn’t like much by placing policemen in the shadows, across from their homes. These days writers and artists can find government spies inside their computers, reading their emails, and trying to track their movements via use of smart phones and credit cards.

Post-Soviet Union, after the fall of the Berlin wall, after the Bosnian war of the 1990s, and after South Africa’s apartheid, the world’s mood was positive. Censorship was out, and freedom was in.

But in the world of the new censors, governments continue to try to keep their critics in check, applying pressure in all its varied forms. Threatening, cajoling and propaganda are on one side of the corridor, while spying and censorship are on the other side at the Ministry of Silence. Old tactics, new techniques.

While advances in technology – the arrival and growth of email, the wider spread of the web, and access to computers – have aided individuals trying to avoid censorship, they have also offered more power to the authorities.

There are some clear examples to suggest that governments are making sure technology is on their side. The Chinese government has just introduced a new national security law to aid closer control of internet use. Virtual private networks have been used by citizens for years as tunnels through the Chinese government’s Great Firewall for years. So it is no wonder that China wanted to close them down, to keep information under control. In the last few months more people in China are finding their VPN is not working.

Meanwhile in South Korea, new legislation means telecommunication companies are forced to put software inside teenagers’ mobile phones to monitor and restrict their access to the internet.

Both these examples suggest that technological advances are giving all the winning censorship cards to the overlords.

But it is not as clear cut as that. People continually find new ways of tunnelling through firewalls, and getting messages out and in. As new apps are designed, other opportunities arise. For example, Telegram is an app, that allows the user to put a timer on each message, after which it detonates and disappears. New auto-encrypted email services, such as Mailpile, look set to take off. Now geeks among you may argue that they’ll be a record somewhere, but each advance is a way of making it more difficult to be intercepted. With more than six billion people now using mobile phones around the world, it should be easier than ever before to get the word out in some form, in some way.

When Writers and Scholars International, the parent group to Index, was formed in 1972, its founding committee wrote that it was paradoxical that “attempts to nullify the artist’s vision and to thwart the communication of ideas, appear to increase proportionally with the improvement in the media of communication”.

And so it continues.

When we cast our eyes back to the Soviet Union, when suppression of freedom was part of government normality, we see how it drove its vicious idealism through using subversion acts, sedition acts, and allegations of anti-patriotism, backed up with imprisonment, hard labour, internal deportation and enforced poverty. One of those thousands who suffered was the satirical writer Mikhail Zoshchenko, who was a Russian WWI hero who was later denounced in the Zhdanov decree of 1946. This condemned all artists whose work didn’t slavishly follow government lines. We publish a poetic tribute to Zoshchenko written by Lev Ozerov in this issue. The poem echoes some of the issues faced by writers in Russia today.

And so to Azerbaijan in 2015, a member of the Council of Europe (a body described by one of its founders as “the conscience of Europe”), where writers, artists, thinkers and campaigners are being imprisoned for having the temerity to advocate more freedom, or to articulate ideas that are different from those of their government. And where does Russia sit now? Journalists Helen Womack and Andrei Aliaksandrau write in this issue of new propaganda techniques and their fears that society no longer wants “true” journalism.

Plus ça change

When you compare one period with another, you find it is not as simple as it was bad then, or it is worse now. Methods are different, but the intention is the same. Both old censors and new censors operate in the hope that they can bring more silence. In Soviet times there was a bureau that gave newspapers a stamp of approval. Now in Russia journalists report that self-censorship is one of the greatest threats to the free flow of ideas and information. Others say the public’s appetite for investigative journalism that challenges the authorities has disappeared. Meanwhile Vladimir Putin’s government has introduced bills banning “propaganda” of homosexuality and promoting “extremism” or “harm to children”, which can be applied far and wide to censor articles or art that the government doesn’t like. So far, so familiar.

Censorship and threats to freedom of expression still come in many forms as they did in 1972. Murder and physical violence, as with the killings of bloggers in Bangladesh, tries to frighten other writers, scholars, artists and thinkers into silence, or exile. Imprisonment (for example, the six year and three month sentence of democracy campaigner Rasul Jafarov in Azerbaijan) attempts to enforces silence too. Instilling fear by breaking into individuals’ computers and tracking their movement (as one African writer reports to Index) leaves a frightening signal that the government knows what you do and who you speak with.

Also in this issue, veteran journalist Andrew Graham-Yool looks back at Argentina’s dictatorship of four decades ago, he argues that vicious attacks on journalists’ reputations are becoming more widespread and he identifies numerous threats on the horizon, from corporate control of journalistic stories to the power of the president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, to identify journalists as enemies of the state.

Old censors and new censors have more in common than might divide them. Their intentions are the same, they just choose different weapons. Comparisons should make it clear, it remains ever vital to be vigilant for attacks on free expression, because they come from all angles.

Despite this, there is hope. In this issue of the magazine Jamie Bartlett writes of his optimism that when governments push their powers too far, the public pushes back hard, and gains ground once more. Another of our writers Jason DaPonte identifies innovators whose aim is to improve freedom of expression, bringing open-access software and encryption tools to the global public.

Don’t miss our excellent new creative writing, published for the first time in English, including Russian poetry, an extract of a Brazilian play, and a short story from Turkey.

As always the magazine brings you brilliant new writers and writing from around the world. Read on.

© Rachael Jolley

This article is part of the autumn issue of Index on Censorship magazine looking at comparisons between old censors and new censors. Copies can be purchased from Amazon, in some bookshops and online, more information here.