20 Oct 2021 | Opinion, Ruth's blog, United Kingdom

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Sir David Amess, MP for Southend West in Essex. Photo: John Stillwell/PA Archive/PA Images

On Monday afternoon British politicians united in memory of a fallen colleague. In shock, those that knew him best spoke one after another of the good man that they knew – Sir David Amess. After a weekend of tears and horror, as once again we tried to come to terms with another brutal attack on our democracy, it was the stories of the man who embodied British democracy – who dedicated his life to his constituents and who as one of the longest-standing parliamentarians in the UK had offered a smile and a word of support and friendship to every new member as they joined him in Westminster – which provided comfort to his friends and colleagues.

I was one of those who benefitted from that smile and support and it’s his smile that I will strive to remember in the months and years ahead, but it’s also a smile I have struggled to emulate in the hours since I learned of his brutal murder on Friday.

Sir David’s murder was an act of terrorism. It was an attack on every democratic value that we hold dear. It was devastating. It also wasn’t the unique – to either the UK or democracies around the world. Ideologues and extremists have throughout history targeted our elected representatives as the ultimate attack on our democracy. Assassination is the ultimate attempt to silence opposition, to incite fear and to undermine the very values that we live by. By its very nature it is also an attack on our collective free speech. And this was an attack that personally shook me to my core – again.

Friday brought back every horrendous memory of Friday 16 June 2016, the day that my colleague and friend, Jo Cox, was assassinated by a far-right extremist. On that Friday I was in a meeting when a member of my team asked me to follow them into the hall to tell me Jo had been attacked. My mum arrived at my office is tears and in the days that followed I and my former colleagues, in the middle of our grief, had to decide how, and if, we could still do the jobs as elected representatives.

We collectively decided to keep going, to take precautions but fundamentally to make sure that our democracy held strong. That isn’t to say that that decision came without cost. Our families worried every day about our security. Our political discourse got increasingly toxic and abuse and threats became even more prevalent. Within weeks of Jo’s murder I received thousands of pieces of abuse and death threats which meant I had to move home.

This level of abuse and intimidation of our elected representatives is unacceptable. Things have to change. Our democracy is precious and we need to cherish it, to defend it and most importantly to defend it. So for Jo, for Sir David and for everyone that bullies and extremists have tried to silence – we must say enough is enough. Things have to change. This is too important to leave to chance.

And to my former colleague, the man with the generous smile – Sir David, may you Rest in Peace. And may your memory be a blessing for everyone who knew you.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Sep 2020 | News, Opinion

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”114664″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”right”][vc_column_text]Frédéric Boisseau

Franck Brinsolaro

Jean Cabut

Elsa Cayat

Stéphane Charbonnier

Philippe Honoré

Bernard Maris

Ahmed Merabet

Mustapha Ourrad

Michel Renaud

Bernard Verlhac

Georges Wolinski

These people were brutally murdered on 7th January 2015. Their “crime” was to work for the French satirical publication Charlie Hebdo.

Whatever your views on the content of the magazine, on their cartoons, their editorial line and their publication of an image of the Prophet Mohammed, the reality is that these people were massacred because of a cartoon. They didn’t threaten anyone. They just went to work on a normal day and were never to return to their families.

This week a terror trial has commenced in France. Fourteen people are charged with being accomplices to the terrorists who murdered 12 people at the offices of Charlie Hebdo, injured a further 11 people and then two days later murdered four people at a Jewish supermarket.

These were acts of terror. Designed to silence and scare. They were attacks on free expression and on freedom of religious belief. They were a hate crime. And even worse they led to more hate, more fear and more abuse towards the French Muslim community.

Index won’t publish the names of the perpetrators. These people sought to divide their country. They sought to sow the seeds of hate and distrust. They are not worthy of our time or consideration.

Today we remember the victims, the survivors and their friends and families. There is nothing more to say.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Dec 2018 | Campaigns -- Featured, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, Statements

On 12 September, the European Commission published a proposal for a Regulation on preventing the dissemination of terrorist content online. The proposal is very problematic from a fundamental rights and free expression perspective. Index on Censorship joins others in highlighting these concerns.

Dear Ministers,

The undersigned organisations are dedicated to protecting fundamental human rights, including the right to freedom of expression and information, both online and offline. We urge you to significantly amend the ‘Regulation on preventing the dissemination of terrorist content online‘, proposed by the European Commission on 12 September 2018, to bring it in line with the Charter of Fundamental Rights, and to propose evidence-based measures that can better achieve the Regulation’s stated goals.

Preventing and countering terrorism, regardless of the ideological, political or religious motivations of the perpetrators, is a legitimate and important goal for European governments that seek to protect liberty and security for individuals and societies. EU Member States and institutions are taking numerous initiatives that aim to counter the threat of violence, including addressing content online that is perceived as promoting terrorism.

One such initiative is the Directive on Combating Terrorism, adopted in March 2017. This Directive has provisions which cover similar content to the Regulation currently being debated – notably in requiring Member States to ensure the “prompt removal of online content constituting a public provocation to commit a terrorist offence” – but its effectiveness has not yet been analysed due to a lack of implementation in all Member States. Without evidence to demonstrate that the existing laws and measures, and in particular the aforementioned Directive, are insufficient to address the harm of terrorist content online, the proposed Regulation cannot be deemed justified and necessary. EU institutions must always ensure that all legislation is evidence-based, appropriately balanced, and consistent with human rights requirements. The undersigned do not believe the proposed Regulation meets these criteria.

Several aspects of the proposed Regulation would significantly endanger freedom of expression and information in Europe:

- Vague and broad definitions: The Regulation uses vague and broad definitions to describe ‘terrorist content’ which are not in line with the Directive on Combating Terrorism. This increases the risk of arbitrary removal of online content shared or published by human rights defenders, civil society organisations, journalists or individuals based on, among others, their perceived political affiliation, activism, religious practice or national origin. In addition, judges and prosecutors in Member States will be left to define the substance and boundaries of the scope of the Regulation. This would lead to uncertainty for users, hosting service providers, and law enforcement, and the Regulation would fail to meet its objectives.

- ‘Proactive measures’: The Regulation imposes ‘duties of care’ and a requirement to take ‘proactive measures’ on hosting service providers to prevent the re-upload of content. These requirements for ‘proactive measures’ can only be met using automated means, which have the potential to threaten the right to free expression as they would lack safeguards to prevent abuse or provide redress where content is removed in error. The Regulation lacks the proper transparency, accountability and redress mechanisms to mitigate this threat. The obligation applies to all hosting services providers, regardless of their size, reach, purpose, or revenue models, and does not allow flexibility for collaborative platforms.

- Instant removals: The Regulation empowers undefined ‘competent authorities’ to order the removal of particular pieces of content within one hour, with no authorisation or oversight by courts. Removal requests must be honoured within this short time period regardless of any legitimate objections platforms or their users may have to removal of the content specified, and the damage to free expression and access to information may already be irreversible by the time any future appeal process is complete.

- Terms of service over rule of law: The Regulation allows these same competent authorities to notify hosting service providers of potential terrorist content that companies must check against their terms of service and hence not against the law. This will likely lead to the removal of legal content as company terms of service often restrict expression that may be distasteful or unpopular, but not unlawful. It will also undermine law enforcement agencies for whom terrorist posts can be useful sources in investigations.

The European Commission has not presented sufficient evidence to support the necessity of the proposed measures. The Impact Assessment accompanying the European Commission’s proposal states that only 6% of respondents to a recent public consultation have encountered terrorist content online. In Austria, which publishes data on unlawful content reports to its national hotline, approximately 75% of content reported as unlawful were in fact legal. It is thus likely that the actual number of respondents who have encountered terrorist content is much lower than the reported 6%. In fact, 75% percent of the respondents to the public consultation considered the internet to be safe.

The Regulation, as proposed, would introduce serious risks of arbitrariness and have grave consequences for freedom of expression and information, as well as for civil society organisations, investigative journalism and academic research, among other fields.

We urge Members of the European Parliament and Member State representatives to significantly amend the Regulation. In this regard, they should prioritize providing evidence for why this instrument is justified and necessary considering the recent adoption of the Directive on Combatting Terrorism. If evidence proves the Regulation justified and necessary, it is imperative for the EU institutions to bring it in line with the Charter of Fundamental Rights, namely the right to privacy in Art.7, to data protection in Art.8 and to freedom of expression and information in Art.11.

Signatories

Access Now

Apti

Bits of Freedom

Center for Democracy and Technology (CDT)

Chaos Computer Club

CILD

Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

Dataskydd.net

Digitalcourage

Digital Rights Ireland

European Digital Rights (EDRi)

Electronic Frontier Finland

Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF)

epicenter.works

Fitug

Free Knowledge Advocacy Group

Frënn vun der Ënn

Homo Digitalis

Human Rights Watch (HRW)

Index on Censorship

Initiative für Netzfreiheit

IT-Political Association of Denmark

Panoptykon

Reporters Without Borders

The Civil Liberties Union for Europe (Liberties)

Web Foundation

Wikimedia Foundation

XNet

Signing in an individual capacity. Affiliation is for identification purposes only.

Daphne Keller

Director of Intermediary Liability

Center for Internet and Society

Stanford Law School

Joan Barata, PhD

Intermediary Liability Fellow

Center for Internet and Society

Stanford Law School

26 Oct 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Wall Street Journal reporter Ayla Albayrak

Last week, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal was convicted of producing “terrorist propaganda” in Turkey and sentenced to more than two years in prison.

Ayla Albayrak was charged over an August 2015 article in the newspaper, which detailed government efforts to quell unrest among the nation’s Kurdish separatists, “firing tear gas and live rounds in a bid to reassert control of several neighborhoods”.

Albayrak was in New York at the time the ruling was announced and was sentenced in absentia but her conviction forms part of a growing pattern of arrests, detentions, trials and convictions for journalists under national security laws – not just in Turkey, the world’s top jailer of journalists, but globally.

As security – rather than the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms – becomes the number one priority of governments worldwide, broadly-written security laws have been twisted to silence journalists.

It’s seen starkly in the data Index on Censorship records for a project monitoring media freedom in Europe: type the word “terror” into the search box of Mapping Media Freedom and more than 200 cases appear related to journalists targeted for their work under terror laws.

This includes everything from alleged public order offences in Catalonia to the “harming of national interests in Ukraine” to the hundreds of journalists jailed in Turkey following the failed coup.

This abusive phenomenon started small, as in the case of Turkey, with dismissive official rhetoric that was aimed at small segments — like Kurdish journalists — among the country’s press corps, but over time it expanded to extinguish whole newspapers or television networks that espouse critical viewpoints on government policy.

While Turkey has been an especially egregious example of the cynical and political exploitation of terror offenses, the trend toward criminalisation of journalism that makes governments uncomfortable is spreading.

Mónica Terribas, journalist for Catalunya Rádio

In Spain, the Spanish police association filed a lawsuit against Mónica Terribas, a journalist for Catalunya Rádio, accusing her of “favouring actions against public order for calling on citizens in the Catalonia region to report on police movements during the referendum on independence.

The association said information on police movements could help terrorists, drug dealers and other criminals.

Undermining state security is a growing refrain among countries seeking to clamp down on a disobedient media, particularly in countries like Russia. In December 2016, State Duma Deputy Vitaly Milonov urged Russia’s Prosecutor General to investigate independent Latvia-based media outlet Meduza’s on charges of “promoting extremism and terrorism” for an article published the day before.

The piece written by Ilya Azar entitled, When You Return, We Will Kill You, documents Chechens who are leaving continental Europe through Belarussian-Polish border and living in a rail station in Brest, a border city in Belarus. Deputy Milonov said he considers the article a provocation aimed at undermining unity of Russia and praising terrorists.

German journalist Deniz Yucel

In Turkey, reporting deemed critical of the government, the president or their associates is being equated with terrorism as seen in the case of German journalist Deniz Yucel who was detained in February this year.

Yucel, a dual Turkish-German national was working as a correspondent for the German newspaper Die Welt. He was arrested on charges of propaganda in support of a terrorist organization as well as inciting violence to the public and is currently awaiting trial, something that could take up to five years.

Ahmed Abba

Outside of the European region, journalists regularly fall foul of national security laws. In April, journalist Ahmed Abba was sentenced to 10 years behind bars by a military tribunal in Cameroon after being convicted of non-denunciation of terrorism and laundering of the proceeds of terrorist acts. Accompanying the decade-long sentence was a fine of over $90,000 dollars. Abba, a journalist for Radio France International, was detained in July of 2015. He was tortured and held in solitary confinement for three months.

The military court allegedly possessed evidence against Abba, who was barred from speaking with the media during his trial, which they found on his computer. Among the alleged evidence was contact information between Abba and the Islamist terrorist group Boko Haram. Abba, who was in the area to report on the Boko Haram conflict, claimed he obtained the information that was discovered on his phone from various social media outlets with the intent of using them for his report.

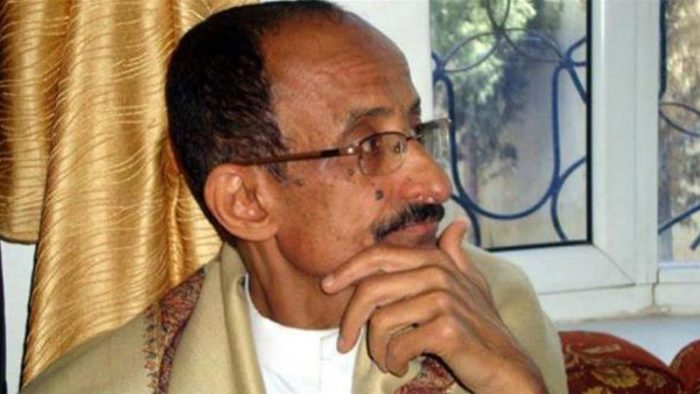

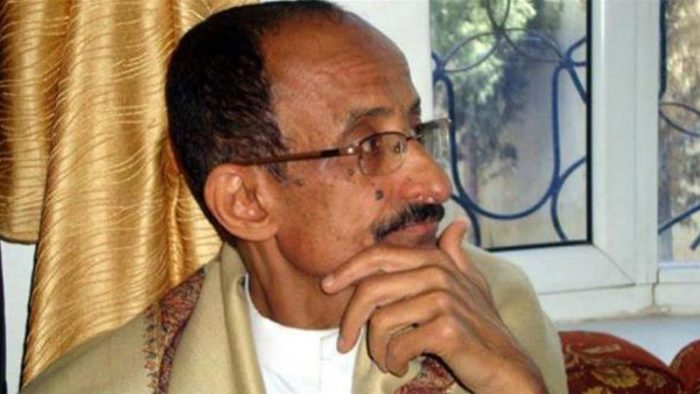

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb al-Jubaihi

Yemeni journalist Yahya Abduraqeeb Al-Jubaihi was sentenced to death earlier this month for allegedly serving as an undercover spy for Saudi Arabian coalition forces. Al-Jubaihi, who has worked as a journalist for various Yemeni and Saudi Arabian newspapers, has been held in a political prison camp ever since he was abducted from his home in September 2016.

Al-Jubaihi is the first journalist to be sentenced to death in Yemen following a trial that many activists believe was politically motivated because of Al-Jubaihi’s columns criticising Houthis.

Journalist Narzullo Akhunjonov

Increasingly, governments are turning to Interpol to target journalists under terror laws. Turkey has filed an application to seek an Interpol arrest warrant for Can Dündar, demanding the journalist’s extradition. In September, Uzbek journalist Narzullo Okhunjonov was detained by authorities in Ukraine following an Interpol red notice.

Uzbek authorities have issued an international arrest warrant on fraud charges against Okhunjonov, who had been living in exile in Turkey since 2013 in order to avoid politically motivated persecution for his reporting.

And governments are also using terror laws to spy on journalists. In 2014, the UK police admitted it used powers under terror legislation to obtain the phone records of Tom Newton Dunn, editor of The Sun newspaper, to investigate the source of a leak in a political scandal. Police powers under the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act, which circumvents another law that requires police to have approval from a judge to get disclosure of journalistic material.

No laughing matter

The Sun editor Tom Newton Dunn

Even jokes can land journalists in trouble under terror laws. Last year, French police searched the office of community Radio Canut in Lyon and seized the recording of a radio programme, after two presenters were accused of “incitement to terrorism”.

Presenters had been talking about the protests by police officers that had recently been taking place in France. One presenter said: “This is a call to people who people who killed themselves or are feeling suicidal and to all kamikazes” and to “blow themselves up in the middle of the crowd”.

One of the presenters was put under judicial supervision and was forbidden to host the radio programme until he appeared in court.

Radio Canut journalist Olivier Combi explained that the comment was ironic: “Obviously, Radio Canut is not calling for the murder of police officers, as it was sometimes said in the press”, he said. “Things have to be put back in context: the words in question are a 30 seconds joke-like exchange between two voluntary radio hosts…Nothing serious, but no media outlet took the trouble to call us, they all used the version of the police.”

Fighting back to protect sources

Two Russian journalists — Oleg Kashin and Alexander Plushev — are pushing back, Meduza reported. Kashin and Plushev filed the lawsuit challenging Russia’s Federal Security Service’s demands that instant messaging apps turn over encryption keys for users’ private communications, which is being driven by Russia’s anti-terror legislation. The court rejected the suit with the judge reportedly found that the government’s demands do not infringe on Plushev’s civil rights.

The journalists had contended that the FSB’s demand violated their right to confidential conversations with sources. Kashin said that in his work as a journalist he had come to rely on apps such as Telegram to conduct interviews with politicians.

Human rights organisation Agora is representing Telegram in a separate case against the FSB, which has fined the app company for failing to comply with its demands.[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96229″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/turkish-injustice-scores-journalists-rights-defenders-go-trial/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

About 90 journalists, writers and human rights defenders will appear before courts in the coming days[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”96183″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/10/interpol-the-abuse-red-notices-is-bad-news-for-critical-journalists/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Since August, at least six journalists have been targeted across Europe by international arrest warrants issued by Turkey, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Mapping Media Freedom” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times-circle” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Since 24 May 2014, Mapping Media Freedom’s team of correspondents and partners have recorded and verified 3,597 violations against journalists and media outlets.

Index campaigns to protect journalists and media freedom. You can help us by submitting reports to Mapping Media Freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Don’t lose your voice. Stay informed.” use_theme_fonts=”yes”][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship is a nonprofit that campaigns for and defends free expression worldwide. We publish work by censored writers and artists, promote debate, and monitor threats to free speech. We believe that everyone should be free to express themselves without fear of harm or persecution – no matter what their views.

Join our mailing list (or follow us on Twitter or Facebook) and we’ll send you our weekly newsletter about our activities defending free speech. We won’t share your personal information with anyone outside Index.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][gravityform id=”20″ title=”false” description=”false” ajax=”false”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row]