5 Aug 2022 | Afghanistan, Belarus, Brazil, Indonesia, Kenya, News, Poland, Russia, South Africa, United Kingdom

Belarus Free Theatre’s Dogs of Europe in rehearsal. Photo: Mikalai Kuprych

Index on Censorship has always supported the theatre of resistance, and our Winter 2021 magazine even had this issue as its main theme.

In Belarus, for example, organisations such as Belarus Free Theatre are crucial to fighting Lukashenka’s ruthless regime. Playwrights in Turkey have also faced government censorship throughout history and have to find their way around it.

In the UK, theatre censorship was officially abolished in 1968, putting an end to over 200 years of control by the Lord Chamberlain. Countries like Brazil are also making things harder for the arts and theatre sector through a kind of financial censorship linked to ideological values.

Now, we explore the universe of theatre and censorship, looking back at pieces published in our magazine.

Staging dissent: When a British prime minister was not amused by satire, theatre censorship followed. We revisit plays that riled him, 50 years after the abolition of the state censor

In this piece published in 2018, actor and director Simon Callow revisited the struggle to officially abolish censorship in theatre in the UK, which happened in 1968, after lasting for almost 200 years.

He explains why vigilance is still needed nowadays and writes about other forms of censorship, such as self-censorship.

Theatre Censorship

In August 1980, Anna Tamarchenko wrote a piece about the strict and recurrent censorship in Russian theatre.

She exemplifies her point of view citing Russian plays that only hit the stage years after being written, such as Boris Godunov, first staged in 1870, 45 years after it was published. Alexander Pushkin, its author, had already passed away 30 years earlier.

“Under the Soviet regime censorship has gained new opportunities to exert pressure on theatrical life,” Tamarchenko wrote.

Alternative theatre

In this piece published in 1985, theatre critic Agnieszka Wójcik (pseudonym) dives deeply into the censorship and repression against student theatre in Poland, especially following the introduction of Martial Law in December 1981, when student theatre began to be considered a threat to public order.

“The repressions following December 13 therefore somehow ‘objectively’ defined the status of student theatre as suspect, if not downright illegal. After the banning of NZS (the independent student union) which had taken most student groups under its wing during the Solidarity period, they lost the foundations of their material existence,” Wójcik wrote for Index.

Why the Taliban wanted my brave mother dead…

For the 2021 Winter issue of Index magazine, Associate Editor Mark Frary reported on the play The Boy with Two Hearts, written by Afghan author Hamed Amiri and inspired by his memories of his mother’s campaigns for women’s rights and why they had to leave Afghanistan behind.

“When Hamed Amiri was 10 years old he watched his mother Fariba give a speech in his hometown of Herat, Afghanistan, speaking out for women’s rights and education and against the ruling Taliban. A day later, a mullah gave the order for Fariba’s execution and the family began a gruelling 18-month journey through Europe,” Frary writes.

Testament to the power of theatre as rebellion

In December 2021, critic, columnist and cultural historian Kate Maltby wrote about Belarus Free Theatre’s journey towards performing at the Barbican in London in 2022.

She talked to Nikolai Khalezin, playwright and journalist, and Natalia Koliada, theatre producer. Both founded Belarus Free Theatre in March 2005 and told Index about the rollercoaster they’ve been through after going into exile in order to escape from Lukashenka’s dictatorship.

“Since 2011, Khalezin and Koliada have held political asylum in the UK, a necessity for survival in the face of repeated harassment and imprisonment at the hands of Lukashenka’s regime”, writes Maltby.

Where silence is the greatest fear

Published in December 2021, this piece written by Issa Sikiti da Silva, Index contributing editor based in West Africa, looks at the censorship suffered by Kenyan theatre and how it has dragged under a series of corrupt leaders.

He also investigates the legacy left by colonial Britain in Kenya and how it still impacts theatre in the country.

“There was hope that Jomo Kenyatta’s ascension to the presidency in 1964 would help heal the wounds inflicted by the British and pave the way to tolerance, social justice, freedom and prosperity,” Da Silva writes.

God waits in the wings…ominously

Brazil is also home to its share of theatre censorship and free speech issues. In December 2021, Index’s editorial assistant Guilherme Osinski and former associate editor Mark Seacombe reported on a presidential decree that art must be sacred. They explored how it has affected Brazilian theatres across the country.

Osinski and Seacombe interviewed two Brazilian theatre companies, which shared their thoughts on president Jair Bolsonaro’s approach to art in Brazil, comparing the current situation to when the country faced a bloody dictatorship from 1964 to 1985.

“While the overt and ruthless censorship of the military dictatorship that ended in 1985 is now history, theatre today has to comply with a nebulous concept known as “sacred art” or be starved of public funds”, writes Osinski.

Desegregating the theatre

In August 1985, Professor Stephen Gray wrote for Index and explained how theatre in South Africa was shaped and controlled by the law, before this censorship was eventually relaxed and became less strict.

“Theatre itself is debate, and in South Africa, where sensitive issues ignite like flash-paper, to each show its own controversy,” Gray writes.

Play politics: policing theatre in Indonesia

At the beginning of the 1990s, Indonesia’s government had promised more openness and freedom for theatre companies in the country. However, president Suharto closed the doors on Jakarta’s popular theatre and other plays began to be banned across Indonesia.

Andrea Webster reported on that issue for Index in July 1991, emphasising the ironies between Suharto’s speech for democracy and the bans and curbs on theatres.

“The ban occurred just over a month after President Suharto himself made an Independence Day speech on 17 August where he spoke of ‘openness’ and democracy, where ‘differences of opinion had their place in Indonesian society,’” Webster wrote on the occasion.

Sending out a message in a bottle: Actor Neil Pearson, who shot to international fame as the sexist boss in the Bridget Jones films, talks about book banning and how the fight against theatre censorship still goes on

In June 2019, then editor in chief of Index on Censorship, Rachael Jolley, interviewed actor Neil Pearson about why governments fear books being published and how the fight against theatre censorship still goes on.

Among many things, they discussed self-censorship and the boundaries between a play which is acceptably controversial and unacceptably controversial.

“If you are genuinely against censorship, you have to be evenhanded against censorship. If your idea of freedom of speech is only allowing people to say what you already agree with, then Goebbels would have no problem with that definition of speech,” Pearson told Index.

‘Humpty Dumpty has maybe had the last word…’

One of the biggest names in British theatre recently wrote for Index on Censorship. Sir Tom Stoppard, playwright and screenwriter and whose work covers themes such as human rights, censorship and political freedom, wrote in December 2021 on how the battleship over freedom still lies between the individual and the state.

30 Dec 2021 | Artistic Freedom, Magazine, News, Turkey, Volume 50.04 Winter 2021, Volume 50.04 Winter 2021 Extras, Wales

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”118071″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]I am a woman kicked out of Heaven.

I am a writer tried for treason, facing life in prison.

I am an exile defined as others.

I am autistic, pushing myself to be normal.

Only to become invisible.

I’m 52 years old. Since childhood, I have always felt alienated from my environment. The more petulant I became, the more walls I built between myself and the world, the greater the desire to flee grew. Not knowing from whom and from what I’m running away, only having the desire to shelter somewhere else, anywhere else. It is hard to be weird and different to others but not know why.

It has done irreparable damage to my self-esteem. I felt trapped inside a cocoon woven of my unhappiness. I was a thing apart. Other people were strictly separate from me. I felt this separation keenly.

This distinction was so clear in my childhood, as a young girl and even now it is the same…

For years, I established completeness in my inner world with all my broken fragments. Without expectation, motionless, distant, introverted. I drowned in words, definitions, tasks… I forgot my essence. I learned to mask myself because I have always been judged.

I have a lot of voices in my mind, ghosts of decades-old voices. Telling me how I should be…

In 2011 I wrote an absurd play called Mi Minör set in a fictional country called Pinima. During the performance, the audience could choose to play the President’s deMOCKracy game or support the Pianist’s rebellion against the system. The Pianist starts reporting all the things that are happening in Pinima through Twitter, which starts a role-playing game (RPG) with the audience. Mi Minör was staged as a play where an actual social media-oriented RPG was integrated with the physical performance. It was the first play of its kind in the world.

Blamed for the Gezi Park protests

A month after our play finished, the Gezi Park demonstrations in Istanbul started. On 10 June 2013, the pro-government newspaper Yeni Şafak came out bearing the headline ‘What A Coincidence’, accusing Mi Minör of being the rehearsal for the protests, six months in advance. The article continued, “New information has come to light to show that the Gezi Park protests were an attempted civil coup” and claimed that “the protests were rehearsed months before in the play called Mi Minör staged in Istanbul”.

After Yeni Şafak’s article came out, the mayor of Ankara started to make programmes on TV specifically about Mi Minör, mentioning my name.

In one he showed an edited version of one of the speeches that I made six years ago about secularism, misrepresenting what I said in such a way that it looked like I was implying that secularism was somehow antagonistic to religion.

What I found so brutal was that the mayor did this in the knowledge that religion has always been one of the most sensitive subjects in Turkey. What upset me most was the fear I witnessed in my son’s eyes and the anxiety that my partner was living through.

Arikan interviewed over Mi Minor

The play was being discussed regularly on TV, websites and online forums and both Mi Minör and my name were being linked to a secret international conspiracy against Turkey and its ruling party, the AKP. Many of the comments referenced the 2004 banning of my book Stop Hurting my Flesh. I received hundreds of emails and tweets threatening rape and death as a result of this campaign.

For three nightmarish months, we were trapped in our own house and did not set foot outside. One day, I saw that one of my prominent accusers was tweeting about me for four hours. The sentences he chose to tweet were all excerpts from my research publication The Body Knows, taken out of context and manipulating what I had written. Those tweets were the last straw.

Wales is protecting me

I left our house, our loved ones, our pasts. We left in a night with a single suitcase and came to Wales, which had always been my dream country. I never imagined my arrival in Cardiff would be like this; feeling bitter, broken and incomplete.

Two years later my partner, who had remained in Turkey, and I got married. In the first month, I learned my husband had brain cancer. Operations, chemotherapy, radiotherapy followed… Within a year, I lost him. I visited him, but sadly I wasn’t able to go to his funeral because of new accusations levelled against me. This was a turning point in my life. I lost my husband. I lost my trust in people. I lost my savings to pay for his care. I lost everything.

In all of this emotional turmoil, I started walking every day for five or six hours. Geese became my best friend and my remedy. I walked for months. I walked and walked everywhere, in the mountains, in the valleys, at the seaside.

These walks had a transformative effect on me. I had discovered a way to live as a woman who had learned to accept herself, rather than a shattered and a lost woman.

Maybe there is an umbilical cord, beyond my consciousness, between me and the wild nature of Wales. I feel this land always wrapped itself around me, talked to me like a mother during the difficult time in my life. For this reason, I wrote my latest play; Y Brain/Kargalar (Crows), written in Welsh and Turkish and produced by Be Aware Productions. It describes my story, the special place this land has in my life and how it transformed me. The title refers to my constant companions during this time – the crows. One reviewer called it “unashamedly lyrical…even as it touches on dark themes”.

On 20 February 2019, as the play was being staged, a new indictment was issued against 16 people, including me, over Mi Minör; I now face a life sentence. Because of this absurd accusation, I feel ever more strongly that Wales is protecting me.

My diagnosis

It was at this time that I was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome/autistic spectrum disorder and I’ve received many answers about myself as a result. From this moment, a new discovery and understanding started. I set out to discover myself with this new knowledge. As soon as I could know who I’m not, I could find out who I am.

I realise that my wiring system simply makes it harder for me to do many things that come naturally to other people. On the flip side, it is important to be aware that autism can also give me many magical perceptions that many neurotypicals simply are not capable of. I believe I was able to write Mi Minör because of my different perceptions.

I have therapy twice a week and I have started to understand what I have been through all my life. My therapists told me that I was manipulated and I was emotionally and sexually abused by whom I love and trust the most; it was a big shock for me. I spent half of my life trying to help abused victims, and I never thought I was a victim. They said this is very common because autistic women are not aware of when they were used. How could I have been so blind?

I couldn’t work out that I was being played by others, like a fish on a line. As an autistic, communication is about interpreting with a basic belief in what people tell me because I don’t tell lies myself. But I have learned how much capacity for lies exists. Autistic people can be gullible, manipulated and taken advantage of. But I learned that regret is the poison of life, the prison of the soul.

The most significant benefit of this process is that I am learning again like a child to re-evaluate everything with curiosity and enthusiasm. It also gives me the chance to reconstruct the rest of my life without hiding myself, being subjugated to anyone, and living without fear.

Autism diagnosis and discovery were liberating for me. There is still not enough autism spectrum awareness even today. That is why I decided to come out about my autism. I strongly believe that if those of us who are on the autistic spectrum share our experiences openly, then it wouldn’t only help other autistic people, it would help neurotypical people to better understand both us and our behaviour.

Looking back at the last few years, I have been thrown into navigating most of the challenging aspects and life experiences and there has been a complete cracking of all masks.

This process is not easy at all, sometimes my soul, sometimes my heart, sometimes all my cells hurt, but it also causes me to recognise a liberation I have never known before.

Fortunately, during this process, I have been learning a lot about myself and how I have masked myself as an Aspie-woman… For me, masking myself is more harmful even than not knowing I’m autistic. Masking means that I create a different Meltem to handle every situation. I have never felt a strong connection with my core. When I am confronted with emotional upset, my brain immediately goes into “fix it” mode, searching for a way to make the other person feel better so I can also relieve my own distress.

For most of my life, I’ve allowed myself to fit in with how I thought others wanted me to feel and act, especially those I loved. My dark night gave me so much pain I broke free and started to care for myself and heal. Taking me back to my primordial self, not the heroic one that burns out, to step back from the battle line of existence, to remember the gods and spiritual parts of nature, my own nature and the person I was at the beginning.

The last two years have been exciting for me. It is as if I died and was reincarnated again. In the end, I understand that my true nature is not to be some ideal that I have to live up to. It’s ok to be who I am right now, and that’s what I can make friends with and celebrate. I learned it’s about finding my own true nature and speaking and acting from that. Whatever our quality is, that’s our wealth and our beauty. That’s what other people respond to. I’m not perfect, but I’m real…[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Dec 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 50.04 Winter 2021

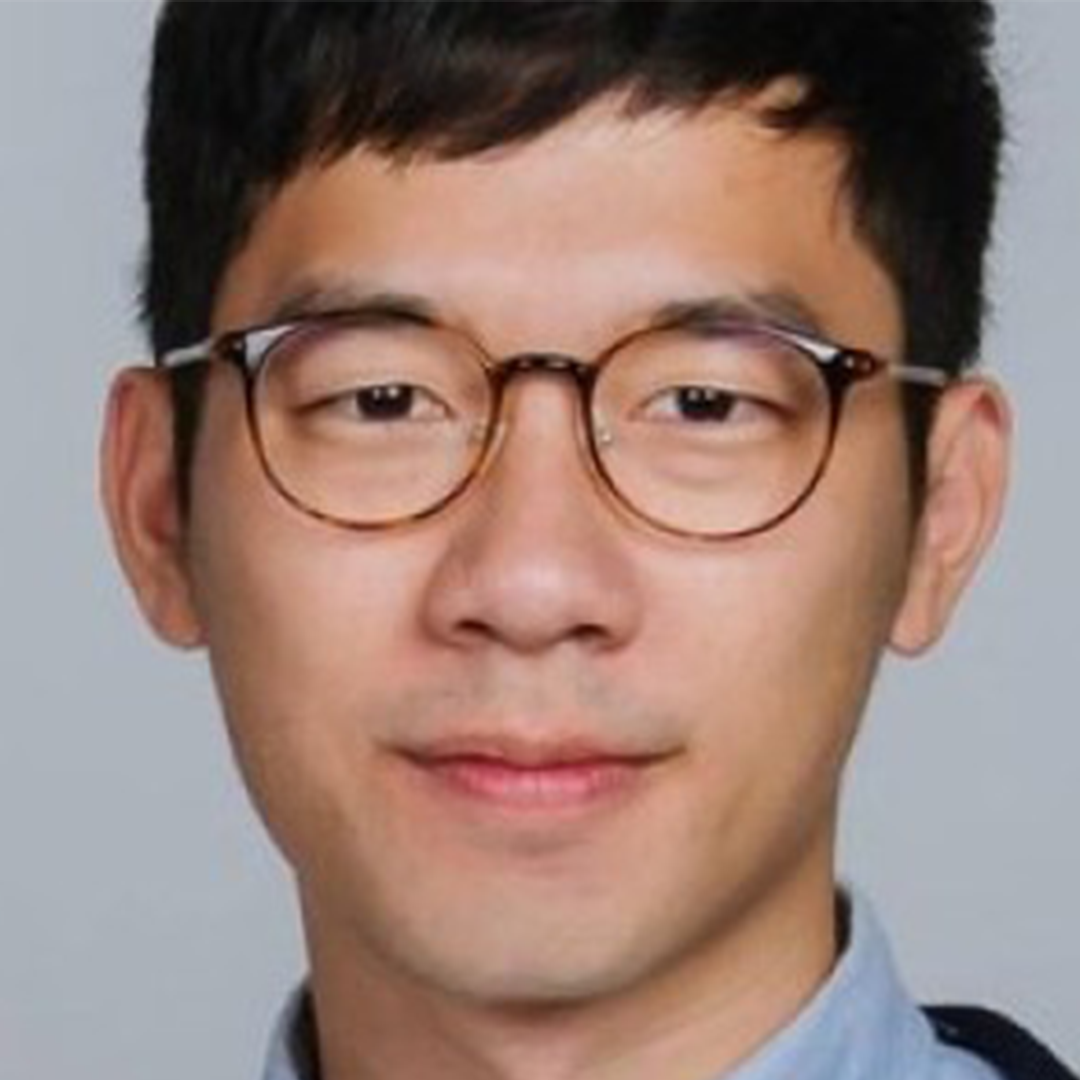

Playwright

Meltem Arikan is a Turkish and Welsh author who was short-listed for the Freedom of Expression Award in 2014 by Index on Censorship for her play Mi Minor.

Journalist

Caitlin May McNamara is a journalist and a campaigner who lives in London.

Activist

Nathan Law is an activist and politician from Hong Kong. In 2016, at 23, he was elected to work as a legislator for Hong Kong, being the youngest lawmaker to ever occupy a chair in the Legislative Council of Hong Kong.

15 Dec 2021 | Artistic Freedom, Events, Magazine, News, Turkey, Wales

Death threats targeting a playwright who has become the target of the Turkish government; self-censorship that messes with your thoughts and changes how a play is written – these were just two things that were discussed as part of the launch this week of the winter issue of Index on Censorship magazine, Playing With Fire: How theatre is resisting the oppressor. In this new issue, writers, playwrights and actors discuss how the world of theatre is facing and confronting censorship around the globe. As reflected in the magazine and at the event, which was held on Monday, the theatre world still has the strength to bring people together, despite censorship.

The launch event specifically focused on Turkey and featured a conversation between the playwright Meltem Arikan and the writer Kaya Genç. The conversation was led by Kate Maltby, critic, columnist, scholar and deputy chair of Index on Censorship’s Board of Trustees.

Arikan told the audience that her first experience of censorship dates back to 2004, when her novel Yeter Tenimi Acıtmayın (Stop Hurting my Flesh) was banned by the Committee to Protect Minors from Obscene Publications.

“I protested a lot and nobody joined me. Before my book was banned, people loved watching me on television. I was openly talking about women. Now I can see that censorship is a similar problem all around the world, not only in Turkey,” said the Turkish and Welsh author who was short-listed for the Freedom of Expression Award in 2014 by Index. Arikan’s play Mi Minor was accused by the Turkish authorities as provoking the Gezi Park protests in 2013. She says that after Mi Minor was performed, she received death and rape threats constantly: “If you are a woman they focus more on your gender.”

The production of Meltem Arikan’s Mi Minör play.

Censorship also restrains people’s ideas, almost like putting an ideological filter inside someone’s brain.

“Self-censorship affects the tone of your writing, including the adjectives you use. I started writing in English for Index, which gave me a great amount of liberty,” said Genç, a journalist who lives in Istanbul and is a contributing editor for the magazine.

Genç told everyone watching the event that Turkish theatre was flourishing when Mi Minör’s play came out, although most of the plays were about torture and Turkish prisons in the 1980s, instead of contemporary Turkey.

“It’s very important that people like Meltem speak out. I see forced exile in Turkey as a tragedy,” he continued.

In Arikan’s words, she had to give up on Turkey. Today, she feels at peace with that decision.

“In Wales I feel I found my home. I’m so happy here. When I came here, at first I tried to give up on writing, but I couldn’t. There is a difference of attitude in the United Kingdom.”

She said: “We need more courageous writers in theatre.”

Maltby, who has written a piece for this edition on Belarus Free Theatre, said that one thing that clearly comes to mind when she thinks about theatre and dissent is theatre’s power to bring people together

“It’s a unique moment where there are a bunch of people who have never met before, but are suddenly physically inhabiting the same space, even in the social media landscape,” she said.

Playing With Fire: How theatre is resisting the oppressor, is out next week. Click here for information on how to read it.