Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

It is still hot in the shade of the palm trees and stuccoed buildings on the American University in Cairo’s (AUC) downtown campus. Groups of refugees sit around on wicker chairs.

It is still hot in the shade of the palm trees and stuccoed buildings on the American University in Cairo’s (AUC) downtown campus. Groups of refugees sit around on wicker chairs.

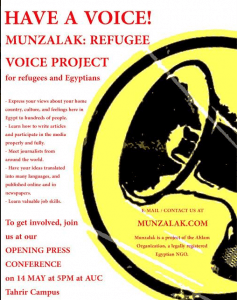

Everyone is here to learn about journalism. Munzalak is a new organization that aims to get refugees living in Egypt involved in the media and in command of their own voice. The name translates to “your comfortable place,” like a home from home – the one you were forced to leave.

Every weekend Munzalak hires out a room at AUC. Refugees are invited to come along and learn the basics of journalism for free. Aurora Ellis, a news editor for an international news agency, runs the workshops with aim of producing “articles that deal with refugee issues and with the refugee experience.”

The ultimate aim is to give refugees a space to voice their experiences. A blog on Munzalak’s website publishes pieces written by refugees (with the option of writing under a pseudonym) while training goes on and – organizers hope – more people join.

Similar initiatives have existed. The Refugee Voice was a newspaper based in Tel Aviv run by African asylum seekers and Israelis inside Israel and founded in April 2011, but is no longer published. Radar, a London-based NGO, also trains local populations in areas around the world (including Sierra Leone, Kenya and India) with the aim of connecting isolated communities.

“We’re being given the opportunity to write about our experiences…I can write about my experiences, and interview other refugees about theirs,” says Edward, a Sudanese refugee who arrived in Cairo earlier this year.

“We have several basic problems – in housing, security, education and health.” He quietly tells stories of life in Egypt; harassment and assault in the streets and pervasive racism (even, he says, from some people who are there to help). “We live a separated life. We are here by force only.”

Ultimately, Edward wants to write a history of the Nuba Mountains, the war-torn area straddling the border between Sudan and South Sudan, where he was born in over 25 years ago. Edward carries a notebook with ideas for this book – scribbled notes of a people and culture disappearing; histories of war and exodus. Edward sees his journalism as self-preservation, telling stories that other people don’t want to be told. He most admires Nuba Reports, a non-profit news source staffed by Sudanese reporters, which aims to break reporting black-spots while humanitarian crises and fighting continues on the ground.

Some activists working alongside refugees see initiatives like this as an important way to break the silence.

“Before June 30, refugees were always neglected in the national media. They were only included [the media] if they were being used as scapegoats,” says Saleh Mohamed from the Refugee Solidarity Movement (RSM) in Cairo. Famous examples include right-wing TV host Tawfik Okasha calling for Egyptians to arrest and attack Syrian and Palestinian refugees on sight. Syrians and Palestinians arrested by security forces have been routinely referred to as “terrorists” by the authorities, a narrative often repeated verbatim by pro-regime newspapers. “Now I think the media wants to keep refugees in the shadows and not talk with them,” Mohamed adds. “You never hear about refugees.”

But Munzalak is not without its risks and challenges. Staying independent but still being able to attract funding and support is one thing. Another is security.

Last Sunday 13 Syrians were sentenced to five years in prison after protesting in March 2012 against Bashar al-Assad. They were charged with illegal assembly and “threatening…security [forces] with danger,” something the defendants all denied, according to state-run newspaper Al-Ahram. A UNHCR official last year had told Syrian refugees to stay away from domestic politics – a warning that could feasibly include journalism as well.

Although historically repressive towards journalists during the rule of Hosni Mubarak, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) and the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s media landscape has taken a significant nosedive since the July coup. Several journalists have been killed in the violence; Mayada Ashraf, a young reporter for Al-Dostour became the latest casualty after she was shot in the head during a protest, allegedly by a police sniper; while reporters remain behind bars and on trial for doing their job.

So is it a good idea to get refugees involved?

Mohamed says that street reporting and visibly working as journalists could put refugees – like Edward – “in danger.” Their legal ability to work also depends on what refugee status they have.

“But otherwise they can talk about themselves rather than waiting for journalists to approach them instead…They definitely need a voice.” But for some refugees, other priorities come first.

Jomana is a 20-year-old Syrian refugee and media studies undergraduate, originally from Aleppo. She visited Munzalak once and liked the idea, but is more concerned about getting a job and paying her way than talking about her experiences – which, like so many Syrian refugees in Egypt nowadays, are harsh. Of almost 184,000 refugees living in Egypt, according to mid-2013 figures from the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), around 130,000 of that number are Syrians.

“I don’t have enough money to continue my studies so I will have to leave,” she explains plainly. Jomana’s home was bombed out during the war and they fled the country with just their passports, arriving in Cairo over two years ago. Eventually her father went back to Aleppo to try and restart his old factory, but returned to find rubble. He came back to Cairo to economic uncertainty, incitement and political instability. “Other people are going back to Syria and dying there. Those that stay [here] aren’t dying from bombing or from fighting…but from hunger.”

Munzalak might help, but for some refugees, not in the most crucial of ways.

“It means I can express my opinion freely,” Jomana says, “but will I get paid for my opinion?”

This article was published on June 20, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

Mayada Ashraf

While Egypt’s hugely controversial Al-Jazeera trial has been grabbing international attention, the recent death of 22-year-old reporter Mayada Ashraf – allegedly at the hands of the police – appears to have left more of a lasting impact on Egyptian journalists working amid the ongoing violence.

On Tuesday, Al-Jazeera “Marriot Cell” defendants again appeared in court to face charges of complicity in terrorism and “spreading false news.” Journalists at the hearing were temporarily booted out, while the judge in the chaotic session admitted he could not understand several pieces of audio evidence aired during the trial. The case has cemented in many people’s minds around the world the idea that Egypt is now a place of kangaroo courts; a dire environment for press freedoms, home to repressive anachronisms that everyone who remembers Tahrir Square in 2011 may be forgiven for thinking were a thing of the past. They’re not.

On March 28 Ashraf, a reporter with Al-Dostour, was gunned down while covering clashes between Muslim Brotherhood supporters and police in Ain Shams, eastern Cairo. Videos showed her corpse being rushed to safety as blood poured over her face. She died soon after.

Ashraf became the fifth reporter to die while reporting on clashes in Egypt since June 30, according to Committee to Protect Journalists figures. And while it may have been a month ago, the death of a young female journalist (who purportedly wrote last August that “Morsi is not worth dying for but Sisi is also not worth renouncing our humanity for”) has had a lasting impact in Egypt.

Press freedom campaigners have been collecting testimonies and eyewitness accounts from the day Ashraf died, an attempt to establish what really happened beyond the claims of the security apparatus.

Forensics officials suggested the shooter was from the Brotherhood, offering a series of exacting distances, heights and perspectives on where the gunman was when Ashraf was hit. The gunman was a few metres away from Ashraf, and probably standing on a car or pavement when she died, claimed senior forensics physician Hisham Abdel Hamid. Interior Minister Mohamed Ibrahim defended the role of security forces that day.

However Journalists Against Torture, a group aiming to build solidarity and offer help among journalists, has spoken to two eyewitnesses who contradict the official account of that day.

“As a journalist, you usually rely on the first eyewitnesses,” explains Journalists Against Torture’s Ashraf Abbas, tucked away in a corner of a café in Cairo’s Boursa district. “And two eyewitnesses said [the shot] came from the security forces.” One of those eyewitnesses, another journalist, was close to Ashraf when the bullet hit her head.

Abbas believes these testimonies carry more weight. “For us, this is more credible than what the Interior Ministry says…They rush into lies before they’ve had time for a proper investigation.” Mohamed Ibrahim’s denial came just two days after Ashraf was shot.

The state’s response, often in the face of contrary evidence, has been used before to absolve itself of any possible blame from a string of controversial deaths.

In November, Cairo University engineering student Mohamed Reda was fatally shot with cartouche (birdshot) as police moved in on a campus protest. The Interior Ministry denied firing anything other than tear gas, before video evidence explicitly disproved that claim. The government then blamed “Brotherhood students” for Reda’s death.

Forensics and ministry officials subsequently claimed the police did not use–or even possess–the rounds which killed Reda. The shooter must have been a Brotherhood student, they argued.

Mohsen Bahnasy is a lawyer who contributed to the investigation into killings during the November 2011 Mohamed Mahmoud Street clashes, events now seen as a case study in disproportionate, lethal force by the Egyptian police. Bahnasy told Index in November that four-millimeter and 8.5-millimeter birdshot found at Mohamed Mahmoud has since appeared in the corpses of students (like Reda) killed in the post-July crackdown – deaths that have been blamed on the Brotherhood.

“Now they have something to hang all their problems on,” Abbas claims, referring to the Brotherhood bogeyman theory used by the authorities to write off deaths, terrorism and even a recent outbreak of tribal violence which left almost 30 dead in Aswan in southern Egypt.

“The killing of Mayada Ashraf was a real wake-up call for the journalistic community. And it has certainly raised serious concerns about how the journalistic community is taking action to protect its own people,” says Aidan White, director of the London-based Ethical Journalism Network.

Al-Dostour editor Essam Nawabi resigned in protest against the death of his colleague. Photojournalists have also launched a series of brief strikes and demonstrations to demand better conditions and protections. This growing anger amongst Egypt’s media community has often reached the doors of the Journalists’ Syndicate, long accused of not doing enough to protect journalists.

Journalists have claimed the police are deliberately targeting them. During clashes between students and police at Cairo University two weeks ago which left one student dead, two journalists were also seriously injured: Khaled Hussein was shot in the chest with live ammunition, while Amr Abdel-Fattah received birdshot wounds. Another photojournalist, Amru Salahuddien, claimed police “intentionally” targeted journalists inside the university: “I was hiding behind a palm which they kept firing at for at least one minute,” he tweeted shortly afterwards.

“A lot of the anger that we’ve seen among rank-and-file journalists in Egypt, particularly younger rank-and-file journalists, is being aimed not just at the authorities (for their failure to provide protection), but also the Journalists’ Syndicate,” White says.

The syndicate has since agreed to donate 100 bulletproof vests and helmets, and promises field reporters will be safe in the future. But are small acts of solidarity by journalists going to change things? “The momentum comes and goes,” Abbas admits, drawing parallels with the fierce debate over press freedoms after “Black Wednesday” in 2005, when mobs sexually assaulted female protesters and journalists during protests. “Now there is momentum again, but we can’t depend on this…we have to make solid gains, pass laws and build something solid.”

Until then, journalists in Egypt are still at risk. For some, Mayada Ashraf’s death is a case study in how the state responds to violence it is accused of carrying out with disregard and impunity. White argues the response could easily be different.

“Was this a killing by groups supportive of the Muslim Brotherhood, or were these thugs working for the police?” he asks. “The only way to find that out is to have a proper investigation. That is what is required.”

Additional reporting by Abdalla Kamal

This article was originally posted on 24 April 2014 at indexoncensorhip.org