Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

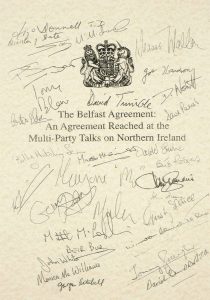

A copy of the Belfast Agreement signed by the main parties involved and organised by journalist Justine McCarthy of the Irish Independent newspaper. Photo: Whyte’s Auctions

Every day the professional staff at Index meet to discuss what’s going on in the world and the issues that we need to address. Where has been the latest crisis? What do we need to be aware of in a specific country? Where are elections imminent? Do we have a source or a journalist in country and, if not, who do we know? During these meetings we are confronted with some of the worst heartbreak happening in the world. Journalists being murdered, dissidents arrested, activists threatened and beaten, academics intimidated and while we know that we are helping them by providing a platform to tell their stories it can be soul destroying to be confronted by the actions of tyrants and dictators every day.

Which is why grabbing hold of good news stories helps keep us on track. The moments when we’ve helped dissidents get to safety, when a tyrant loses, when an artist or writer or academic manages to get their work to us. These are good days and should be cherished for what they are – because candidly they are far too rare.

It’s in this spirit that I’ve absorbed every news article, reflection and op-ed column discussing events in Northern Ireland 25 years ago. I was born in 1979, my family lived in London – the Troubles were a normal part of the news. As I grew up, the sectarian war in Northern Ireland seemed intractable, peace a dream that was impossible to achieve. But through the power of politics, of words, of negotiation, peace was delivered not just for the people of Northern Ireland but for everyone affected by the Troubles. That isn’t to say it was easy, or straightforward and that it doesn’t remain fragile, but it has proven to be miraculous and is something that we should both celebrate and cherish.

The Good Friday Agreement delivered the opportunity of hope for the people of Northern Ireland. It gave us a pathway to build trust between communities and allowed, for the first time in generations, people to think about a different kind of future. For someone who firmly believes in the power of language, who values the world of diplomacy and fights every day for the protection of our core human rights there is no single moment in British history which embodies those values more than what happened on 10 April 1998.

We can only but hope that other seemingly intractable disputes continue to see what happened in Belfast on that fateful day as inspiration to challenge their own status quo.

Index on Censorship considers Tony Blair’s proposals on hate speech to be dangerous and divisive. Blair, who is to be appointed chair of the European Council on Tolerance and Reconciliation (ECTR) has defended plans to lower the the barriers on what constitutes incitement to violence and make Holocaust denial illegal.

“These suggestions — far from protecting people — are likely to have the opposite effect, driving extremist views underground where they can fester and grow,” said Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship. “Instead, we should be protecting free expression, including speech that may be considered offensive or hateful, in order to expose and challenge those views.”

Individuals should always be protected from incitement to violence and that protection already exists in law, as do stringent laws on hate speech. Further legislation is not needed.

Tony Blair defended his infamous courting of the press at the Leveson Inquiry today, describing it as a “strategic decision” to avoid the wrath of British media groups.

Blair, prime minister from 1997 to 2007, said he was not afraid of taking on the media, but was aware that if he did so he would be mired in a “long protracted battle that will shove everything else to the side.”

During his day-long evidence, which was interrupted by a protester breaking into the courtroom and branding him a “war criminal”, Blair said as a political leader he decided he would “manage that relationship [with the press] and not confront it.”

He repeatedly cited the Daily Mail as attacking him and his family “very effectively”, and slammed the “full-frontal” attacks launched on senior politicians by some sections of the press as “an abuse of power”

“If you fail to manage major forces in the media, the consequences are harsh,” Blair said, adding later that his sole piece of advice to any political leader would be to have a “solid media operation”.

“With any of these media groups, you fall out with them and you watch out,” he said, “because it is literally relentless and unremitting once that happens.”

Blair outlined to the Inquiry, which is currently examining relations between politicians and the press, that ties between the two would inevitably involve “closeness”. These would become unhealthy, he said, “when you were so acutely aware of the power exercised that you got into a situation where it became essential and crucial to have that interaction.”

He said the “imbalance of power” in the relationship was more problematic than the closeness.

However, he defended himself and his party as having “responded” to a phenomenon of media-political closeness than having created it, conceding later that they were “sometimes guilty of ascribing to them [the press] a power that they do not really have.”

His close ties with media mogul Rupert Murdoch are well-documented, with the Murdoch-owned Sun famously backing the Labour party ahead of its landslide win in the 1997 general election. Blair famously flew out to Hayman Island, Australia in 1995 to address Murdoch and News Corp executives, and in 2010 became godfather of Murdoch’s daughter.

When Lord Justice Leveson put it to Blair that the 1995 trip was a “charm offensive”, Blair defended it as a “deliberate” attempt to elicit the support of the Murdoch titles.

“My minimum objective was to stop them tearing us to pieces. My maximum objective was to try and get their support,” he said.

Quizzed about whether the prospect of needing to meet Murdoch in January 1997 had “angered” him, as suggested in Alastair Campbell’s diaries, Blair agreed this was his view and was how he would define the “unhealthy” part of the press-politicians relationship. Such meetings mattered, Blair said, “because the consequence of not getting it right was so severe.”

Yet he stressed he did not “feel under pressure from commercial interests from the Murdoch press or from anybody else”, and denied there were any express or implied deals with him or any other media group.

Blair added that policy was never changed during his time in government as a result of Murdoch, and that his decision not to launch an inquiry into cross-media ownership was not a means of appeasing the News Corp boss. Their relationship until he left office in 2007 was a “working” one, Blair emphasised.

The Inquiry continues tomorrow, with evidence from education secretary Michael Gove and home secretary Theresa May.

Follow Index on Censorship’s coverage of the Leveson Inquiry on Twitter – @IndexLeveson

Next week is set to be one of the most gripping yet in the Leveson Inquiry into press standards.

Monday has been reserved for former prime minister Tony Blair, who will likely be questioned about his close relationship with media mogul Rupert Murdoch, whose tabloid the Sun famously switched its long-standing Conservative allegiance to back the Labour party ahead of the 1997 general election.

Business secretary Vince Cable is scheduled to appear on Wednesday. It is likely he will be quizzed about News Corp’s £8bn bid for the takeover of satellite broadcaster BSkyB, particularly his admission that he had “declared war” on the Murdoch-owned company, which led to his being stripped of responsibility for the bid.

But the highlight will surely come from Thursday’s sole witness, culture secretary Jeremy Hunt, who is fighting for his political life after the revelation of a November 2010 memo he sent to David Cameron in support of News Corp’s £8bn bid for control of the satellite broadcaster one month before he was handed the task of adjudicating the bid.

In the memo Hunt emphasised to Cameron that it would be “totally wrong to cave in” to the bid’s opponents, and that Cable’s decision to refer the bid to regulator Ofcom could leave the government “on the wrong side of media policy”.

The memo has further weakened Hunt’s grip on power, already in doubt after last month’s revelations that his department gave News Corp advance feedback of the government’s scrutiny of the BSkyB bid. Evidence shown to the Inquiry yesterday during News Corp lobbyist Frédéric Michel‘s appearance showed over than 1000 text messages had been sent between the corporation and Hunt’s department, along with 191 phone calls and 158 emails.

The Labour party has since upped the volume on its calls for Hunt to resign, arguing he was not the “impartial arbiter” he was required to be.

Hunt has maintained he acted properly and within the ministerial code, while David Cameron said today he does not regret handing the bid to Hunt, stressing he acted “impartially”.

Follow Index on Censorship’s coverage of the Leveson Inquiry on Twitter – @IndexLeveson