28 May 2012 | Middle East and North Africa

On 24 May, artist and dramatist Rjab Magri was assaulted by four people in El Kef (North West of Tunisia). The assaults occurred few meters outside the prep school where Magri was teaching a drama class. The attackers are believed to be hardline Islamists.

“I felt as if a balcony fell over me or as if my head had blown up. I lost consciousness, and I fell to the ground. I could see four or five persons stamping on me. One of them told me “you are insulting people; we will get rid of all of you.” I asked him “what is your problem with me?” “shut up atheist”, he said as he was hitting my head into the ground, and the others continued stamping on me”, said Magri in a testimony broadcast by Tunisian National TV 1.

The dramatist is recovering at a private medical clinic in Tunis, where he is getting treatment for traumatic brain injury, and clavicle fracture. The attackers also broke his teeth and nose.

Moez M’rabet, the President of the Association for Dramatic Art Graduates, told JawharaFM radio station: “We harshly condemn the assault, the second of its kind against our colleague. We are confused, and shocked because police officers did not interfere, even though they were near the incident”.

“This reminds us of the physical attacks against dramatists which took place on 25 March at Habib Bourguiba Avenue. I hold the ruling authorities responsible for these assaults. Artists are witnessing attacks on a daily basis, and there is complicity on the part of the authorities. I would like to address the public opinion, and inform them that today the Tunisian artist’s physical sanctity is at risk, and so his ideas, and freedoms of expression and creation,” he added.

24 May 2012 | Middle East and North Africa, Uncategorized

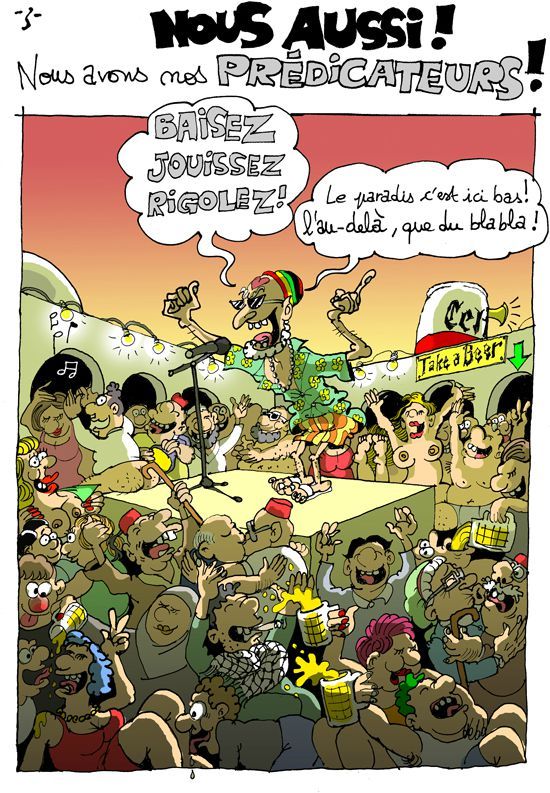

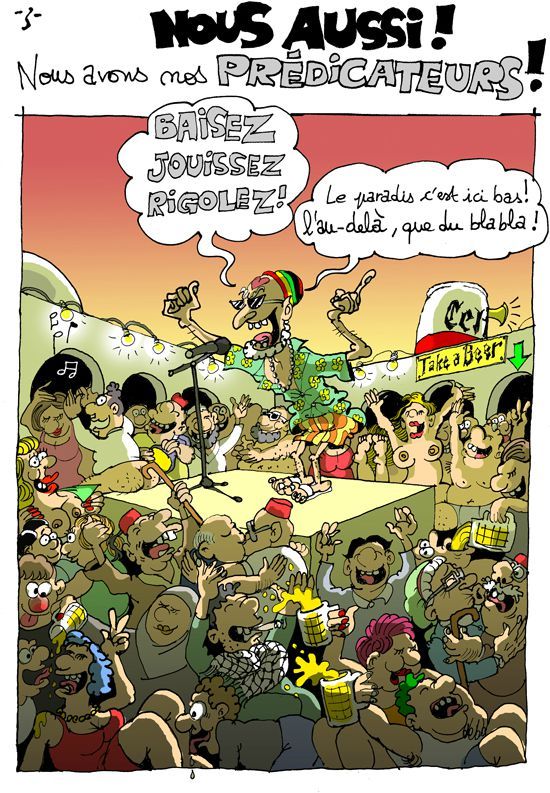

Anonymous renowned Tunisian caricaturist _Z_ is under fire. His bold caricaturist style, no stranger to his fans, has landed him in trouble.

For years, his caricatures mocked Ben Ali’s autocratic and corrupt regime. The regime censored his caricatures, but did not succeed in tracking him down and exposing his identity. In 2009, police arrested blogger Fatma Riahi, and accused her of being behind _Z_.

More than 18 months after the fall of the regime, _Z_ still desires to conceal his identity. His caricatures now target the Islamists of Tunisia. _Z_ knows no boundaries, no red lines. For him anything can be caricatured and ridiculed. Something, many in Tunisia will not like, especially when it comes to what they consider as “sacred”, and “immoral”.

On 18 May, Facebook removed two cartoons by _Z_ following complaints the social networking site received. The cartoonist wrote about the decision on his blog the same day:

“Two caricatures published on my Facebook page DEBA Tunisie have just been censored. Each caricature contains little bit of sex, little bit of politics, and little bit of religion. There will always be an orthodox Tunisian who would snivel about them [caricatures] to Zuckerberg. My friends, according to our morality guardians there is inevitably a boundary that should not be crossed when it comes to tackling the Saint Trinity of the three Tunisian taboos: politics, sex, and God”

One of _Z_’s censored caricatures ridicules the members of Tunisia’s constitutional assembly, showing them taking part in various distracting activities during a meeting, apart from actually drafting the country’s constitution. Two MPs are shown having anal sex, and others are shown masturbating, playing chess and gambling. Another shows a lively party where a “cleric” says: “have sex, enjoy, and have fun. Paradise is down here. Up there is only bla bla bla!”

Some of _Z_’s caricatures also depict god and Prophet Muhammad, considered to be forbidden in Sunni Islam, leading to the launch of a fierce social media campaign against the artist. Tunisian journalist Thameur Mekki, believed by some to be the anonymous artist, has been the target of death threats meant for _Z_.

Both _Z_ and Mekki have denied these allegations. Mekki told Mag14.com that “this is a murder incitement matter” and said he would “lodge a complaint against those who are disseminating lies”.

22 May 2012 | Middle East and North Africa

On 28 May Monatir Appeal Court is expected to issue a verdict in the case of two atheist friends Jabeur Mejri and Ghazi Beji. In March a primary court sentenced the two to a seven-and-a-half year jail term over the publishing of prophet Mohammedd cartoons.

Defense lawyers chose only to appeal on behalf of Jabeur Mejri, since Ghazi Beji has fled the country. “We would lose appeal if we defend him [Ghazi Beji] in absentia”, said Bochra Bel Haj Hmida, a defense lawyer, and a human rights activist.

To convict the two friends, Mahdia Primary Court employed Article 121 (3) of the Tunisian Penal Code, which states the following:

“The distribution, putting up for sale, public display, or possession, with the intent to distribute, sell, display for the purpose of propaganda, tracts, bulletins, and fliers, whether of foreign origin or not, that are liable to cause harm to the public order or public morals is prohibited.”

Anyone who violates this law risks a fine of 120 TND (76USD) to 1200 TND (760 USD), and a jail term of six months to five years.

Article 121 (3), adopted on 3 May 2001 as a way to tighten control over press freedom, was repeatedly used during the post Ben Ali era.

The controversial law earned Jabeur Mejri and Ghazi Beji a five-year jail term, and a 1200TND (760USD) fine for publishing content liable to “disturb public order”, and six months for “moral transgression”. The court also sentenced them to two more years in prison for “insulting others via public communication networks”.

The Court of First Instance of Tunis also used this law to fine both Nessma TV boss Nabil Karoui over the broadcast of French-Iranian film Persepolis, and Nasreddine Ben Saida, the general director of the Arabic-language daily newspaper Attounissia over the publishing of a front page photo of a Real Madrid footballer with his naked girlfriend.

“As lawyers and activists we are volunteering to defend Mejri, and Beji. This is our tool to combat abusive laws adopted during the Ben Ali regime. But it is the job of the legislative branch, that is the national constituent assembly, to amend such laws,” explained Mrs Bel Haj Hmida.

21 May 2012 | Middle East and North Africa

Dictators do not like to be ridiculed. They fear bold political cartoonists. Ousted Tunisian President Zeine el-Abidin Ben Ali made sure that the few artworks of political cartoonists who dared to criticise his regime would not reach the masses. He did what any tyrant would do: he censored them.

For more than four years Seif Eddin Nechi, a young Tunisian cartoonist, has been using social media as a platform to mock and criticise various aspects of the Tunisian society and political landscape. It did not take long before the regime’s net censorship machine blocked access to his cartoons.

Nechi said: “During the Ben Ali era I used to criticise everything, but in a roundabout way to get around censorship. Once I started talking about internet censorship through my cartoons, I was censored”.

He added: “After 14 January 2011 [when the Tunisian revolution began], criticising national and political affairs has become a central theme in my cartoons, with a more direct tone”.

With the uprising and the fall of the Ben Ali regime, many of the red lines which once prohibited artists from revealing their talents were scrapped.

“When I was very young, I used to draw everything and anything (especially my professors), and this earned me several punishments! Due to the system, my interest in caricature art had gradually faded away, and I could only share my drawings with my closest friends,” says Adnen Akremi (alias Adenov).

But now, Adenov can make use of his sense of humour, his pencils and his character Le Rasta, who is always smoking a joint, to ridicule and criticise.

Adenov explained: “It is through him [Le Rasta] that I express myself. He is Zen-like and out of touch and this somehow helps him to hit where it hurts. Through him I try to criticise the Tunisian’s situation in a funny way (well not always funny). When my messages are similar to the majority’s, it is good, but I’m not seeking to be the spokesperson of a particular group or a political party”.

In one drawing, Mustapha Ben Jaafar, Tunisia’s constituent assembly President, is depicted as extremely angry, asking Le Rasta about the efficiency of joints: “Is your thing efficient?” he asks. Le Rasta answers:” I can guarantee that it is 100 per cent efficient. Take one before each assembly session”.

In another cartoon, Le Rasta sarcastically comments on the increase in gas prices and the trend of self-immolations: “Is this within the framework of fighting self immolation suicides?”

Like Adenov, Nechi also created his own character, Bakounawar. “Bakounawar almost always ridicules reality, laughs at everything, he rarely gets angry,” Nechi told Index. “I created him to express myself and to try to say what is on my mind in a quasi-ludic manner, while remaining serious at the same time. Bakounawar has adopted a more popular discourse (and not a populist one) to be more than ever by the side of average and poor Tunisians. Bakounawar chose Tunisian dialect as language, and popular humour. I’m aware that my caricatures are still far from those I want to reach because the platform that I chose (the web) is not accessible to everyone,” he explained.

Via Bakounawar, Nechi has expressed his support to Al-Oula, a weekly newspaper whose director spent seven days on hunger strike protesting at government policies of state advertisements distribution among newspaper. “It [Al-Oula] is not a newspaper worth five cents”, says Bakounawar in one caricature.

But why did these two young artists chose the art of caricature? An art which cost Naji al-Ali’s life, and almost cost Syrian political cartoonist and Index Award winner Ali Fezrat his fingers.

“The message of a caricature is more direct than any other drawing genres”, answered Adenov.

“It is the most ludicrous tool capable of popularising complex situations. Caricatures allow us to laugh at our own flaws…” replied Nechi.

“This art has a primordial role in the construction of the future of a freer Tunisia”, said Amine Lamine, founder of Graphik Island, a platform which seeks to promote the artworks of Tunisian artists at both national and international levels. “Popularising art and culture to make them more accessible, so as many people as possible have interest in them and take part in the building of a better Tunisia”, he added.

The booming of caricature art was crowned by the publishing of Koumik (Tunisian for “Cartoon”), a collective book of comics which brought together 14 rising Tunisian caricaturists. The first issue was published in October 2011, and other issues are expected and anticipated.