13 Apr 2017 | News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

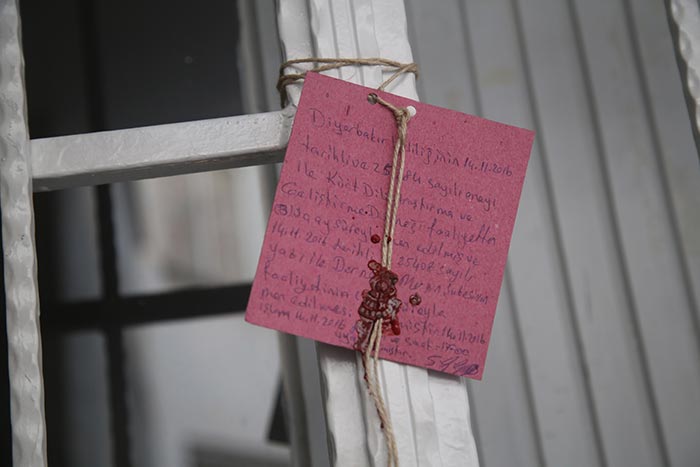

Kürt Yazarlar Dernegi, tarihi Sur ilçesindeki eski Diyarbakir evlerinden birini Özgür Gazeteciler Cemiyeti ile birlikte kullaniyordu. Dernegin es baskanlari Reso Ronahî ile Yildiz Çakar, üyeleriyle birlikte dernegin avlusunda bekliyorlar. Dernegin kapisi yeni mühürlenmis.

The Kurdish Writers Association used one of the old Diyarbakır houses in the historical Sur district together with the Free Journalists Society. The association’s co-presidents, Reso Ronahî and Yıldız Çakar, wait outside the association together with members. The association’s doors have been newly sealed [by authorities].

Jiyan Tv Kürtçenin Zazaki lehçesinde yayin yapan ilk televizyon kanaliydi.

Jiyan TV was the first TV channel to broadcast in the Zaza dialect of Kurdish.

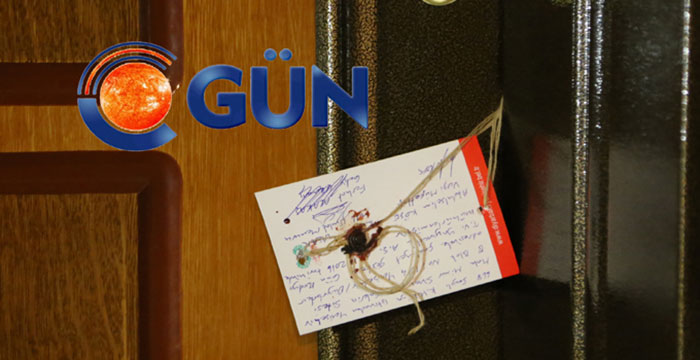

Diyarbakir’da Kürtçe ve Türkçe yayin yapan Özgür Gün Tv, KHK ile kapatildi.

Özgür Gün TV, which broadcast in Diyarbakır in Kurdish and Turkish, was closed by Executive Order.

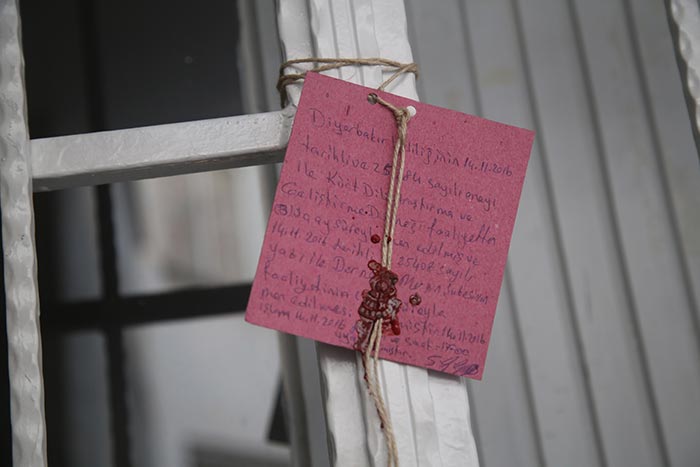

Pek çok il ve ilçede subeleri bulunan Kurdi Der, Kanun Hükmünde Kararname ile kapatildi.

Kurdi-Der (The Kurdish Language Research and Development Association), which had branches in many towns and cities, was closed by Executive Order.

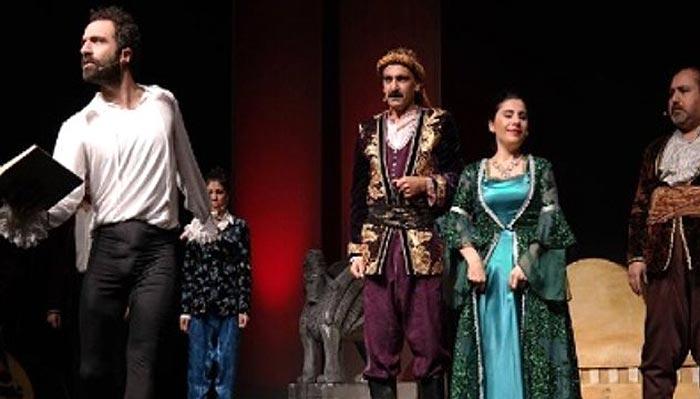

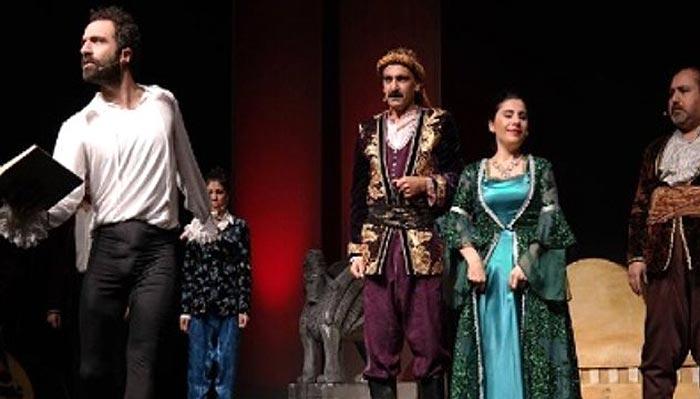

Kürtçe oyunlar sahneleyerek Kürt tiyatrosuna önemli katkilarda bulunan Diyarbakir Büyüksehir Belediyesi Sehir Tiyatrosu, Olaganüstü Hal’in ilanindan sonra kapatilmadi. Ancak belediyeye kayyim ataninca tiyatrocularin tamami isten çikarildi ve tiyatro fiilen kapatilmis oldu.

The Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre, which has made important contributions to Kurdish theatre by putting on Kurdish-language plays, was not closed after the declaration of a state of emergency. However, when a trustee was appointed to the municipality, all the theatre employees were fired and the theatre was de facto closed down.

Kürtçe oyunlar sahneleyerek Kürt tiyatrosuna önemli katkilarda bulunan Diyarbakir Büyüksehir Belediyesi Sehir Tiyatrosu, Olaganüstü Hal’in ilanindan sonra kapatilmadi. Ancak belediyeye kayyim ataninca tiyatrocularin tamami isten çikarildi ve tiyatro fiilen kapatilmis oldu.

The Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality City Theatre, which has made important contributions to Kurdish theatre by putting on Kurdish-language plays, was not closed after the declaration of a state of emergency. However, when a trustee was appointed to the municipality, all the theatre employees were fired and the theatre was de facto closed down.

Dicle Haber Ajansi kurulusundan bu yana çok defa polis tarafindan basildi ve haber konusu oldu. editör ve muhabirleri topluca gözaltina alindi. Internet sitesinin erisimi, 2015’ten kapatildigi 2016 yilina kadar 48 defa engellendi.

From the time the Dicle News Agency was established to the present day, the police have often raided it and it has often been in the news. Its editors and reporters were arrested en masse. Access to the internet site was blocked 48 times in 2015 and 2016.

Dicle Firat Kültür Merkezi, Mezopotamya Kültür Merkezi’nin Diyarbakir’daki subesi. Burada müzik, halk oyunlari, resim gibi kurslar veriliyordu.

The Tigris and Euphrates Cultural Centre was the Diyarbakır branch of the Mesopotamia Cultural Centre. Here there were courses given in areas such as music, folk dancing, and painting.

Kayapinar Belediyesi’ne ait Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi, adini ünlü Kürt sair Cegerxwin’den aliyor. Sanatin bir çok dalinda egitim veren kurum, bugüne kadar yüzlerce ögrenci mezun etti. Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi’nin bir de sergi salonu var.

The Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre belonging to Kayapınar Council takes its name from the famous Kurdish poet Cegerxwîn. Hundreds of students have graduated from the institution, which provides education in many branches of the arts. There is also an exhibition hall at Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre.

Kayapinar Belediyesi’ne ait Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi, adini ünlü Kürt sair Cegerxwin’den aliyor. Sanatin bir çok dalinda egitim veren kurum, bugüne kadar yüzlerce ögrenci mezun etti. Cegerxwin Kültür Merkezi’nin bir de sergi salonu var.

The Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre belonging to Kayapınar Council takes its name from the famous Kurdish poet Cegerxwîn. Hundreds of students have graduated from the institution, which provides education in many branches of the arts. There is also an exhibition hall at Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre.

Cewgerxwin Kültür Merkezi.

Cegerxwîn Cultural Centre.

Türkiye’de Kürtçe yayinlanan ilk günlük gazete olan Azadiya Welat, KHK ile kapatildi.

Turkey’s first daily newspaper in Kurdish, Azadiya Welat, was closed with a state of emergency order.

Merkezi Diyarbakir’da bulunan Azadî Tv, Kürtçe ve Türkçe yayin yapiyordu.

Azadî TV, whose headquarters are located in Diyarbakır, used to broadcast in Kurdish and Turkish.

150’den fazla sergiye ev sahipligi yapan Amed Sanat Galerisi, Diyarbakir Büyüksehir Belediyesi’ne kayyim ataninca sanata kapilarini kapatti.

The Amed Art Gallery, which has played host to over 150 exhibitions, closed its doors to art after a trustee was appointed to Diyarbakır Metropolitan Municipality.[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492093702668-36263af0-9654-0″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

13 Apr 2017 | News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”86316″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]This article is authored by a researcher who has requested anonymity.

Much has been publicised about the crackdown on freedom of expression in the aftermath of the failed coup attempt that transpired on the night of 15 July 2016 in Turkey. This is not the first time that Turkey has experienced a military coup; indeed, violent overthrows of elected governments had already occurred in 1960, 1971 and 1980.

In 1997, the military intervened once more, this by issuing a memorandum that aimed to rein in the Islamist agenda of Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan and his Welfare Party Government. Widely called a “postmodern coup” the military effectively forced him out of office. Each of these coups has engendered a rupture in Turkish political life and has profoundly impacted the realm of arts and culture.

This quality of rupture was perhaps nowhere more contoured than in the military take-over of 12 September 1980, during which the junta under the leadership of Kenan Evren pursued “mass imprisonment, systematic torture, and disappearances” of oppositional, and especially leftist forces. The actual extent of the human rights violations that occurred has yet to be investigated in full but a few figures published by the Istanbul-based Truth, Justice and Memory Center give a glimpse of the social, political and cultural toll of the coup: “according to statistics, approximately 650,000 people were taken into custody, more than 1.5 million were blacklisted by the state, a quarter of a million were put on trial, and 300 lost their lives in various ways.”

Along with disbanding labour unions and limiting freedom of assembly and freedom of the press, the military junta also curtailed academic and artistic expression by establishing the state-controlled Higher Education Council (YÖK) and instituting various mechanisms to pre-screen and censor artworks, especially literary production and films, for years to come. What is often overlooked, however, is that each of these coups has also produced erasure and forgetting in the cultural history of Turkey, not least by curtailing associational life.

Associations that artists were part of were never simply closed, their archives were confiscated too. In this way, the memory of their work was not merely delegitimized but the material traces were likewise destroyed or made inaccessible to the generations that followed. While this dynamic has affected the realm of arts and culture in Turkey in general, the persecution, repression and erasures of Kurdish cultural and artistic production have certainly been the most consistent.

As Kurdish was long classified as an “unrecognised language”, and the existence of Kurds has long been denied in Turkey, Kurdish artistic production has been criminalised and frequently classified as separatist propaganda. Along with individual artists and works of art, Kurdish associational life – as a bedrock of artistic production and cultural reproduction that facilitates the transfer practices, knowledge and memory have been repeatedly targeted; their archives were confiscated and (possibly) destroyed many times over.

What sets this time apart, however, is that the coup attempt actually – and importantly – failed. Yet, the state of emergency declared on 21 July 2016, billed as a necessary tool to investigate the coup and bring the plotters to justice has expanded beyond members of the Gülenist movement to oppositional groups overall by way of Turkey’s vague anti-terrorism legislation. With the extension of the power of the state apparatus, we are, once more witnessing attacks on the field of culture and the arts in general, and Kurdish artistic production in particular.

As investigative journalist Elif İnce reported in January 2017: “Over 1,400 associations and foundations have been shut down with the state of emergency decrees […]. Kurdish arts and culture associations with prominent theatre companies, such as Seyr–î Mesel in Istanbul and various branches of the Mesopotamia Cultural Centre (MKM), are among those permanently shut.”

From September 2016 onwards the AKP government ordered state-appointed trustees to take over the municipalities of several Kurdish cities that had been governed by the pro-Kurdish HDP; their mayors are now facing various charges of aiding and abetting terrorists, and separatist propaganda. These municipalities had been supportive of Kurdish artistic production, both establishing new avenues for artists and assisting initiatives that had been built arduously through grassroots efforts during decades of violence and insecurity. Among the current cases of repression, the de facto closure of the Amed Art Gallery in Diyarbakir through the Ankara-appointed trustee left the city without public facilities to exhibit visual art. The municipal theatre, lauded by the AKP government just a few years ago for performing Hamlet in Kurdish, has likewise been disbanded. The same is true for the city theatres of Batman and Hakkari.

This recent wave of repressions has included sealing off performance and rehearsal spaces, and the confiscation of archives, props, and other equipment. It has extended from municipal theatres in the Kurdish regions to theatre groups affiliated with Kurdish arts and culture associations across the country. Archives are now digital and can be more easily saved, quite in contrast to the 1990s when the MKM were raided repeatedly, threatened by closure, their members often harassed and charged with separatist propaganda based on the mere fact that they pursued artistic production in Kurdish. The Kurdish cultural landscape has been very resilient and experienced in navigating these kinds of repression – and the erasures they engender. But will the same be true for the rest of Turkey’s art world?

Access to the past, to cultural and artistic memory, is intimately connected to freedom of expression. Along with human rights and democratic institutions, cultural memory is once again at stake, and under risk to be erased in Turkey. [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492093371629-c08ef909-721a-10″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

4 Apr 2017 | Digital Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Journalist Nur Ener

It was around 2am on the morning of 3 March 2017 that Turkish police broke the door open to the apartment of Nur Ener, a journalist who works for the daily Yeni Asya. Her house was searched. She was held in custody for three days at the Kocasinan Police Department detention centre in complete isolation before she was arrested on 6 March.

A court ordered her arrest on charges of being affiliated with the Fethullah Gülen network, a religious community which Turkish authorities claim is behind Turkey’s July 15 failed coup. Since then, she has been imprisoned in Bakırköy Women’s Prison in Istanbul. As an alleged member of the group involved in the coup, she is allowed only 45 minutes of family visits a week and only an hour to consult with her lawyer. She is barred from all written communication with the outside world.

It later emerged that her arrest was based on a tip-off from a former flatmate, who was likely coerced into providing names to go free in Turkey’s increasingly Kafkaesque judicial system, where letters or emails are accepted as enough evidence to be arrested on very serious charges by Turkey’s controversial Criminal Judicatures of Peace. Currently, over 150 journalists are imprisoned in the country, almost all accused of terrorism charges, both as part of and outside the coup investigation.

Life before journalism

Nur was born in the city of İzmir in 1991 to a devout Muslim family. Her father, Uğur Ener, is a furniture seller and her mother, Nazan Ener, a housewife. The couple has another daughter, Rana Ener, who is two years older than Nur.

As a child, Nur was very active and curious, according to her mother Nazan Ener. She was a very good student at school but also had a seemingly limitless energy for a wide range of extracurricular activities, from horseback riding to archery. She was brought up in İzmir and lived there, until her admission into the Communications Department of Erzurum University in 2010.

As a leading member of her university’s Communications Student Club, she often organised panels. During such one event, she met with Kazım Güleçyüz, the editor-in-chief of Yeni Asya, the flagship newspaper of a community in Turkey which profoundly respects and adheres to the Risale-i Nur a collection of treatises offering interpretations of the Quran by the 19th-century Sunni theologian Said’i Nursi.

She interned at the newspaper that summer, and was hired formally in 2015, shortly after her graduation.

“When she was four, we were in the yard and her father asked her to bring something. She said she couldn’t walk in that direction because she didn’t want to step on the ants walking outside. She was always very compassionate,” Nur’s distraught mother said.

“Nur was always respectful of other people’s opinions,” she continued. She mentioned the name of a neighbor, whom she referred to as “our grandfather,” a staunchly secular old man, who “had a complete opposite worldview” from the Ener family. “One day, she saw him painting the yard wall, and she jokingly said ‘Grandfather Mevlüt, I can’t let you tarnish your charisma like that with that paint roller!’ and painted the wall herself.”

Most staff at Yeni Asya agrees that Nur is a natural peacemaker, a born mediator. Her mother remembers: “When she was just a schoolgirl, she once forced us to have a positive dialogue with a neighbor who had yelled at Nur for playing soccer infront of her house.” The neighbor was surprised when Uğur Ener politely asked the neighbor what was wrong, instead of arguing for yelling at her daughter. The neighbor never found out that this had happened on Nur’s demand, and in fact Uğur Ener was initially very angry at him.

Assertive journalist

“I shared a flat with Nur,” said Ülker Caba, a fellow editor at Yeni Asya. “She is a very active person. Before she started working at Yeni Asya, she was involved in various projects in the media. For example, I remember she contributed to Bianet [Independent News Network, a secular news website in Turkey with a good reputation for its journalism, funded by SIDA] . She is a great journalist. She was always very insistent about getting interviews for example. She would call a person a thousand times to make sure that she would get an interview.”

“She was very social and very engaged. Starting these Periscope sessions was her idea,” said Kazım Güleçyüz, who met me in his office at Yeni Asya minutes after completing a morning Periscope broadcast on Yeni Asya’s Twitter account. “We often broadcast these together with Nur,” he said.

Ener’s boisterous and energetic personality also made her an active person outside work. “We cycled or took strolls along the shore on the weekends,” says Recep Kılınç, Nur’s fiancé, who works at the newspaper’s accounting department. The couple had set a wedding date for 29 April. Rana, Nur’s sister, was looking for a wedding gown a few days before her arrest.

“She also loved reading, we would talk for hours and sometimes go star-gazing at night.” Kılınç cannot visit his fiancée in prison as per the restrictions imposed on journalists arrested as part of the coup investigation under Turkey’s State of Emergency rules, which went into force on 20 July, five days after the coup attempt.

Speaking of Nur’s initial detention, Kılınç said: “There wasn’t a single female police officer when they came to her house. All male officers raiding the house of a woman who lived alone in the middle of the night,” a deeply offensive act for the devout family. “They seized her laptop, her books; they left the house a mess.”

Interviews that disturbed some

But why was Nur detained and later arrested, nearly after seven months after the coup attempt? Her family says that a former flatmate of Nur had given her name to the police after being detained herself shortly after the coup attempt. She later called Nur and admitted what she had done, and even apologised. Turkey’s so-called “repentance law” allows suspects to be released if they provide more information about an organisation. Still, her newspaper and family find it perplexing that the police would wait so long to continue the investigation. Could it be a message to Yeni Asya, which has so far been spared in the post-coup decimation of news outlets in Turkey? 160 media organisations have been shut down under several Cabinet Decrees under the post-coup State of Emergency rule.

The answer could be a yes, according to Yeni Asya editor-in-chief Güleçyüz. “It is possible. She recently published some reports that disturbed [the Turkish government]” he said. “Most recently, she published an interview with Fatma Bostan Ünsal,” who parted ways with the Justice and Development Party over differences in opinion after being one of its founders. “The interview criticised the State of Emergency implementations. Its headline quoted Ünsal saying ‘We were freer in Feb. 28,’ a reference to the 1997 unarmed military intervention against a religious-minded government, which caused much grievance among Turkey’s conservative segments, who were profoundly affected by the intervention.

Unclear charges

Because there is a confidentiality decision on the investigation, Nur’s lawyers have not been formally informed of the charges she faces. Nor have they been able to see any document pertaining to the investigation. According to the arrest ruling, she was arrested for having downloaded ByLock, a little-known mobile chat application which Turkish officials say was used only by the members of the Fethullah Gülen network. Although the National Intelligence Agency itself has said that the use of ByLock by the group ended long before the coup, thousands have been arrested for downloading the app.

Nur was put under arrest by a ruling of the 4th Criminal Judicature of Peace. An objection filed by her lawyers to another Judicature of Peace was not processed at any point. However, it recently appeared that an indictment has been prepared and submitted to a court — a rare and positive development in Turkey, a habitual offender in terms of using pre-trial detention as a form of punishment for journalists — and Nur will soon be tried by the 26th High Criminal Court, to which the objection was referred; a procedural violation. A court date has yet to be set.

“We are hoping for her release. The fact that they haven’t rejected our objection might mean that she might be released any time,” Güleçyüz said.

Kılınç agreed, smiling optimistically, he said: “Yes, we start every new day with that hope.”[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1491296439514-9b2a04ec-9c56-3″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

3 Apr 2017 | News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Enough is Enough, a play formed as a gig, tells the stories of real people about sexual violence, through song and dark humour. It is written by Meltem Arikan, directed by Memet Ali Alabora, with music by Maddie Jones, and includes four female cast members who act as members of a band.

While touring Wales recently with my new play Enough Is Enough, I thought about what I experienced with my earlier work in Turkey. But which Turkey?

In the so-called “New Turkey”, everything is being surveilled by the government, from plays and books to everything you share on social media. There were no undercover Welsh police or prosecutors sitting in the audience in Newport or Pontypridd.

We designed Enough is Enough as a touring project. We went to 21 different Welsh venues in 21 different places, north, south, east and west, in less than a month. Audience members had strong positive reactions and some suggested that the production should be taken into schools. In the New Turkey even thinking about taking the play to schools would be enough to be accused of something unimaginable. If you dared sing the songs sung in Enough is Enough, you can be sure you would receive a violent reaction.

When you confront reality in a direct way, even if it is through art, governments around the world do not want to hear your voice. The New Turkey’s government is only an extreme example. When you speak truths, governments do not want you to be heard – they do not want you at all.

Yet when you show reality in a direct way, when you slap the audience with pain, the reaction becomes the same everywhere. First they are shocked, then they find you unusual, but in the end they compliment you for doing it.

During our tour of Wales, people let us into their hearts, looked after us and many venues promised to invite us again. Audience members shared their stories with us. Many wanted to work with us, others supported us unconditionally.

After every performance we had “shout it all out” sessions. We heard repeatedly how many of the issues we confront on stage – sexual violence, oppression and misogyny – are being swept under the carpet because people don’t like to discuss them.

These sessions took me back to a time before I wrote Mi Minor, the play accused of being a rehearsal for the Gezi Park protests in 2013. A time before I had to leave the country because of those accusations. A time before the innovations in the New Turkey was not as horrifyingly obvious as they are now. A time when the AKP, the ruling party of Turkey, was backed not just by the liberals in Turkey but liberals around the world. Back then I was told I was wrong about the government. It was in 2007 that I wrote a play entitled I am Breaking the Game.

That play premiered in Zurich and toured to Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Istanbul and Ankara. No matter where it was performed there was a particular reaction that stuck with me: “These issues are not our issues, they belong to the East.”

I was inspired by the stories of people I know personally. I was in touch with the victims of domestic violence, honour killings, rape, incest and sexual abuse. I knew all stories were true. So I wasn’t sure why then so many didn’t see these issues as theirs. I searched and searched for this place far away from everyone and everything, where all these horrible things keep happening, called the “East”. Eventually I found myself in the West.

After graduating from the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, actor Pinar Ogun felt inspired by Breaking the Game. She felt angry that the run of the play was short in Turkey and she became passionate — almost obsessed — to stage it in London. She tried to convince her instructors at LAMDA, artistic directors of various venues and theatre friends to make it happen. She even introduced me to a couple of people who showed interest, but the reaction was again the same: “Of course these issues are very important but these issues are not our issues, they belong to the East. We resolved these issues in the 1970s. Such plays, performances have been done in the past. These are very old discourses.”

Laurie Penny was one of the only people who had a different reaction. She interviewed me nine years ago: “However much she is hounded by Turkish authorities and tutted at by European theatre goers, one thing is certain: Meltem Arikan is not about to roll over and hush. And thank goodness for that.”

When slapped in the face does it hurt less in the West than in the East?

Why is it considered a social phenomenon when women are killed in the name of honour in the East but an individual crime when women are killed in the name of passion, obsession or jealousy in the West? Child marriage in the East is seen as a nightmare. But, in the West, does calling pregnant children “teen moms” prevent their lives from turning into a nightmare?

After I was forced to leave Turkey and began living in Wales, Ogun restarted her campaign to stage I am Breaking the Game. A year ago, I finally said yes. I’ve been observing a West that has been dazzled by the light of past enlightenments, alienated from its very own issues, attached to the chains of concepts and utterly disconnected to its reality. With Ogun’s company, Be Aware Productions, we applied to Arts Council Wales for research and development funding. But even after the grant was awarded, I was afraid I would still hear the echoes of the long-dead rejection: “These issues are not our issues, they belong to the East”, “the stories of the East”, “The East…”

My rejections, my questions, my issues.

During our research process we met with Welsh sex workers, organisations that help and support women facing violence, and victims. My initial idea was to replace these new stories with the stories in the play, but then I decided to write a new play entirely.

I developed the play with stories of abuse, rape and incest from Britain, all true stories, all had actually happened in these lands. Sometimes I used the exact words of the victims, sometimes I made them more poetic, but most importantly, in order to reach the hearts of the audience, I decided to use the magic of music and that’s how the idea of making it a gig-theatre came to be.

My rejections, my questions, my issues.

When writing Enough is Enough, my intention was to become a megaphone to the people who are facing violence here, to point to the elephant in the room by talking about incest and to underline the fact that when it is about the existence of women and men, those in the West and those in the East were the same.

I dare to say this because I can see blatantly that no matter how much cultures, cuisines, languages, clothes, ethnical backgrounds have managed to differentiate each and every one of us, no matter whether we were born in the West or in the East, we’re all forced to have the life forms designed by the patriarchy and so we are all dominated by the same fears for thousands of years.

Just like the East, the West also lives in its own virtual world built on the concepts of the patriarchal culture. And the relative comfort of this world doesn’t mean a thing for the victims. Just like Turkey, just like France, just like Yemen, just like the USA, women, children and men in Britain become victims. Abuse, rape and incest endlessly continue to exist with all its savagery within society, behind closed doors. The pain and consequences of this ongoing violence continue to be ignored. And while children become the children of fear, not the children of their parents, all around the world violence continues to beget violence. Those who face their pain empathise with victims, whereas those who escape their pain empathise with the perpetrators.

During the Wales tour, the reaction from people who were violated, who knew what violence was, who did not escape from their pain, who faced themselves, who were not in denial of their experiences, in short, the reaction from people who knew the pain of reality, was warm, open and stripped-down. We received the biggest support from women’s organisations, women, some brave men, young people and the LGBT community.

On 8 April 2017 at the Wales Millennium Centre and from the 26-29 April at Chapter Arts Centre, we will continue to say “Enough is Enough”. This time our goal is to reach promoters and artistic directors for an England tour. We want to make our voice be heard in England, and shout “Enough is Enough” together with the English audience.

I really wonder about the reaction of the audience in England. Will they be as open as the Welsh audience or will they keep repeating their apologies while saying these are the East’s problems. The irony is that this time we will be coming from the West, at least west of England.

Yet, whatever the reaction of the audience in England may be, I know for sure there won’t be any audience members who try to organise a mob against us.

Whatever the reaction of the audience in England may be, I know for sure the play would never be banned with the accusation of “disturbing the family order”.

Whatever the reaction of the audience in England may be, I know for sure that newspapers won’t run a smear campaign against the actors because of our play.

Whatever the reaction of the audience in England may be, I know for sure I won’t receive any death threats just because I dared to address violence against women. [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

[/vc_column_text][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1491211961521-80d1b694-85da-6″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]