13 Sep 2016 | mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

In mobster movies the bad guys always kidnap the wife of the protagonist. They’ll phone the husband to say: “We have your wife. Do as we tell you otherwise she’s gone.”

I had not imagined that a state could become no better than a criminal syndicate. But the Turkish state has become one.

On Saturday 3 September my wife’s passport was confiscated by the police at the airport as she was en route to Berlin. She was not accused of anything criminal. She was not being searched for or tried and had no obstacles preventing her from travelling abroad. There was no legitimate reason to prevent her journey and no explanation has been given.

It is with me that they had an issue. I had broadcast footage of Turkish state intelligence smuggling arms into a neighbouring country by illegal means. They could not deny it and say: “No such thing has happened.” What they said was: “This is a state secret.”

For uncovering the state’s dirty secrets, I was given five years and ten months in prison. We had appealed the conviction to a higher court but after the coup attempt a state of emergency was declared and the rule of the law was completely suspended.

To expect justice to be served by a judiciary under the complete control of the government would have been as naive as expecting mercy from the “mob”.

I went abroad and said that I would not return until the state of emergency was lifted and the rule of the law was restored.

Then the mob took my wife hostage. We are not the only people to face such relentlessness.

The 64-year-old mother-in-law of one of the supposed coup plotters was taken to a prison in a wheelchair. The father of another accused, who was not caught, was taken into custody as he left prayer in a mosque. The passports of wives and daughters have been confiscated and hundreds of families have been forcefully separated without trial.

These are direct violations of the principle of individual responsibility for crime.

Guilt by association allows such mob-like lawlessness prevails in a country that is a member of the Council of Europe.

It was the present government that brought the coup plotters who tried to overthrow it into the state, tasked them with cleansing its opponents and made a giant out of them.

When they had a dispute over distribution of spoils and dissolved their partnership, there remained within the state a well rooted and gargantuan parallel organisation.

Then the conflict peaked on July 15 when Frankenstein’s monster attacked its creator.

The violent coup attempt was put down because the military headquarters did not lend it support and the people took to the streets. But Erdogan has treated the event — in his own words — as “a godsend”. Using the tactics used by US senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s, he has started a witch hunt that will incarcerate all opposition.

More than 40,000 people have been taken into custody while 80,000 civil servants have been removed from their duties. Dozens of journalists have been arrested. Nearly 100 media outlets have been shut down.

Yet the rage of the government has not been quelled. Now it is taking it out on the relatives of those “witches” it did not catch.

It says: “We have your wife. Come back or she’s gone.”

But we all know that at the end of the movie the bad guys are defeated, the hostages are freed and families are reunited.

I have no doubt that this is what will happen in Turkey. Those who have made a mob out of the state will be tried. Families will get back together and celebrate the end of the witch hunt and the return of freedom, democracy and justice.

We are well aware of this and we labour to make that day come true.

Can Dündar: Turkey is “the biggest prison for journalists in the world”

Turkey should drop criminal charges against journalists Can Dündar and Erdem Gül

11 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

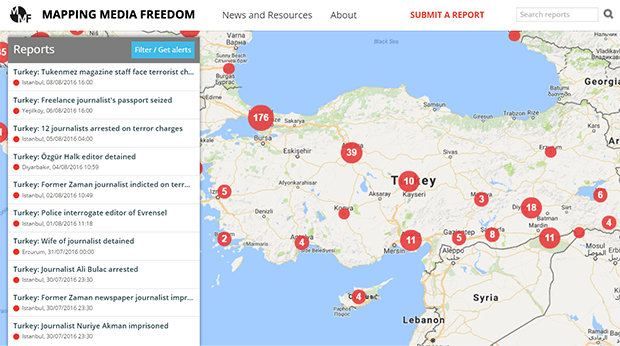

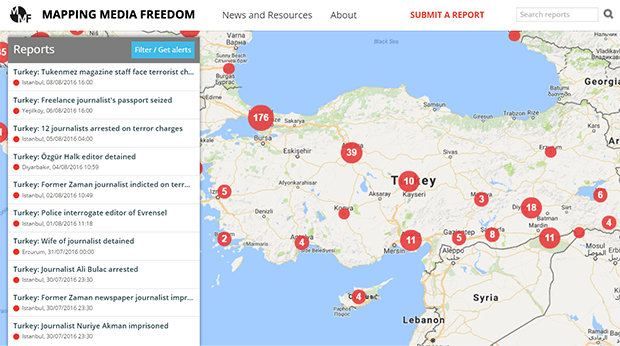

The number of threats to media freedom in Turkey have surged since the failed coup on 15 July.

One of the most vital duties of a journalist — in any democracy — is to report on the day-to-day operations of a country’s parliament. Journalism schools devote much time to teaching the deciphering budgets and legal language, and how to report fairly on political divides and debates.

I recalled these studies when I read an email Wednesday morning from an Ankara-based colleague. I smiled bitterly. The message included a link to an article published in the Gazete Duvar, which informed that 200 journalists had been barred from entering the home of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. Security controls at the two entrances of the failed-coup-damaged building had been intensified and journalists were checked against a list as they tried to enter.

The reason for the bans? Most of those who were blocked worked for shuttered or seized outlets alleged to be affiliated with the Gülenist movement.

Parliament, though severely damaged by bombing during the night of the coup attempt, is still open. For any professional colleague, these sanctions mean only one thing: journalism is now at the absolute mercy of the authorities who will define its limits and content.

Many pro-government journalists do not think the increasingly severe controls are alarming. “It is democracy that matters,” they argue on the social media. “Only the accomplices of the putschists in the media will be affected, not the rest.”

If only that were true. Reality proves the opposite. Along with the closures of more than 100 media outlets, a wide-scale clampdown on Kurdish and leftist media is underway. Outlets deemed too critical of government policies have come under post-coup pressure.

Late Tuesday, pro-Kurdish IMC TV reported that the official twitter accounts of three major pro-Kurdish news sources — the daily newspaper Özgür Gündem and news agencies DIHA and ANF — were banned. Some Kurdish colleagues interpret the sanctions as part of an upcoming security operation in the southeastern provinces of Diyarbakır and Şırnak.

What I see is a new pattern: in the past three-to-four days, many Twitter accounts of critical outlets and individual journalists have been silenced. An “agreement” appears to have been reached between Ankara and Twitter, but no explanation has yet been given.

For days now, many people have been kept wondering about the case of Hacer Korucu. Her husband, Bülent Korucu, former chief editor of weekly Aksiyon and daily Yarına Bakış, is sought by police after an arrest order issued on him about “aiding and abetting terror organisation”, among other accusations. She was arrested nine days ago as police had told the family that “she would be kept until the husband shows up”.

The Platform for Independent Journalism provided more insight on Hacer Korucu’s detention and subsequent arrest. The motive? She had taken part in the activities of the schools affiliated with Gülen Movement and attended the Turkish Language Olympiade.

Hacer Korucu’s case, without a doubt, shows how arbitrary law enforcement has become in Turkey. As a result no citizen can feel safe any longer.

“She is a mother of five,” was the outcry of Rebecca Harms, German MEP. “A crime to be married to a journalist?”

How do we now expect an honest Turkish or Kurdish journalist to answer this question? By any measure of decency, the snapshot of Turkey in the post-putsch days leaves little suspicion: emergency rule gives a free reign to authorities who feel empowered to block journalists from covering the epicenter of any democratic activity — parliament — and let relatives of journalists suffer.

Meanwhile, we are told on a daily basis that democracy was saved from catastrophe on that dreadful July evening and it needs to be cherished.

But, like this? How?

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

10 Aug 2016 | Academic Freedom, Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

The stream may be small right now, a trickle, but it is unmistakable. Turkey’s academics and secular elite are quietly and slowly making their way for the exits.

Some months ago, in the age before Turkey’s post-coup crushing of academia, a respected university lecturer told me she was seeking happiness outside Turkey. She was teaching economics at one of Istanbul’s major universities, but neither her nor her husband, who is also in the financial sector, had a desire to remain in the country any longer. They simply packed up and left for Canada.

The growing unease about the future is now accelerating among the academics and mainly secular elite in the country. This well-educated section of society is feeling the pressure more than any other, and as the instability mounts the urge to join the “brain drain” will only increase.

Some of them, particularly those academics who have been fired and those who now face judicial charges for signing a petition calling for a return to peace negotiations with the Kurdish PKK, no longer see a future for their careers. With the government further empowered by emergency rule decrees, the space for debate and unfettered learning is shrinking.

One of the petition’s signatories, the outspoken sociologist Dr Nil Mutluer, has already moved to a role at the well-respected Humboldt University in Berlin to teach in a programme devoted to scholars at risk.

You only have to look at the numbers to realise why more are likely to follow in the footsteps of those who have already left Turkey. In the days after the failed coup that struck at the country’s imperfect democracy, the government of president Recep Tayyip Erdogan swept 1,577 university deans from their posts. Academics who were travelling abroad were ordered to return to the country, while others were told they could not travel to conferences for the foreseeable future. Some foreign students have even been sent home. The pre-university educational system has been hit particularly hard: the education ministry axed 20,000 employees and 21,000 teachers working at private schools had their teaching licenses revoked.

Anyone with even the whiff of a connection to FETO — the Erdogan administration’s stalking horse for the parallel government supposedly backed by the Gulenist movement — is in the crosshairs. Journalists, professors, poets and independent thinkers who dare question the prevailing narrative dictated by the Justice and Development Party will hear a knock at the door.

It appears that the casualty of the coup will be the ability to debate, interrogate and speak about competing ideas. That’s the heart of academic freedom. The coup and the president’s reaction to it have ripped it from Turkey’s chest.

But it’s not just the academics who are starting to go. The secular elite and people of Kurdish descent that are also likely to vote with their feet.

Signs are, that those who are exposed to, or perceive, pressure, are already doing this. Scandinavian countries have noted an increase in the exodus of the Turkish citizens. Deutsche Welle’s Turkish news site reported that 1719 people sought asylum in Germany in the first half of this year. This number already equals the total of Turkish asylum seekers who registered during the whole of 2015. Not surprisingly, 1510 of applications in 2016 came from Kurds, who are under acute pressure from the government.

The secular (upper) middle class is also showing signs of moving out. The economic daily Dünya reported on Monday that the number of inquiries into purchasing homes abroad grew four-to-five times the pre-coup level. Many real estate agencies, the paper reported, are expanding their staff to meet the demand. Murat Uzun, representing Proje Beyaz firm, told Dünya:

“The demand is growing since July 15 by every day. Emergency rule has also pushed up the trend. These people are trying to buy a life abroad. Ten to twelve people visit our office every day….Many ask about the citizenship issues.”

Adnan Bozbey, of Coldwell Banker, told the paper that people were asking him: “Is Turkey becoming a Middle Eastern country?”

According to Dünya, the USA, Ireland, Portugal, Greece, Malta and Baltic countries are popular among those who want to seek life prospects elsewhere.

In short, the unrest is spreading. Unless the dust settles and the immense political maneuvering about the course Turkey is on reverses, it would be realistic to presume that a significant demographic shift will take place in the near future.

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.