29 Sep 2021 | Afghanistan, Americas, Artistic Freedom Commentary and Reports, Asia and Pacific, Australia, Burma, Cuba, Ecuador, Europe and Central Asia, Israel, Lukashenko letters, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Middle East and North Africa, Religion and Culture, Russia, Syria, Turkey, Uganda, United Kingdom, United States, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

The Autumn issue of Index magazine focuses on the struggle for environmental justice by indigenous campaigners. Anticipating the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), in Glasgow, in November, we’ve chosen to give voice to people who are constantly ignored in these discussions.

Writer Emily Brown talks to Yvonne Weldon, the first aboriginal mayoral candidate for Sydney, who is determined to fight for a green economy. Kaya Genç investigates the conspiracy theories and threats concerning green campaigners in Turkey, while Issa Sikiti da Silva reveals the openly hostile conditions that environmental activists have been through in Uganda.

Going to South America, Beth Pitts interviews two indigenous activists in Ecuador on declining populations and which methods they’ve been adopting to save their culture against the global giants extracting their resources.

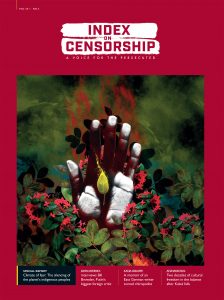

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

A climate of fear, by Martin Bright: Climate change is an era-defining issue. We must be able to speak out about it.

The Index: Free expression around the world today: the inspiring voices, the people who have been imprisoned and the trends, legislation and technology which are causing concern.

Pile-ons and censorship, by Maya Forstater: Maya Forstater was at the heart of an employment tribunal with significant ramifications. Read her response the Index’s last issue which discussed her case.

The West is frightened of confronting the bully, by John Sweeney: Meet Bill Browder. The political activist and financier most hated by Putin and the Kremlin.

An impossible choice, by Ruchi Kumar: The rapid advance of Taliban forces in Afghanistan has left little to no hope for journalists.

Words under fire, by Rachael Jolley: When oppressive regimes target free speech, libraries are usually top of their lists.

Letters from Lukashenka’s prisoners, by Maria Kalesnikava, Volha Takarchuk, Aliaksandr Vasilevich and Maxim Znak: Standing up to Europe’s last dictator lands you in jail. Read the heartbreaking testimony of the detained activists.

Bad blood, by Kelly Duda: How did an Arkansas blood scandal have reverberations around the world?

Welcome to hell, by Benjamin Lynch: Yangon’s Insein prison is where Myanmar’s dissidents are locked up. One photojournalist tells us of his time there.

Cartoon, by Ben Jennings: Are balanced debates really balanced? Ask Satan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Special Report” font_container=”tag:h2|font_size:22|text_align:left”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Credit: Xinhua/Alamy Live News

It’s not easy being green, by Kaya Genç: The Turkish government is fighting environmental protests with conspiracy theories.

It’s in our nature to fight, by Beth Pitts: The indigenous people of Ecuador are fighting for their future.

Respect for tradition, by Emily Brown: Australia has a history of “selective listening” when it comes to First Nations voices. But Aboriginal campaigners stand ready to share traditional knowledge.

The write way to fight, by Liz Jensen: Extinction Rebellion’s literary wing show that words remain our primary tool for protests.

Change in the pipeline? By Bridget Byrne: Indigenous American’s water is at risk. People are responding.

The rape of Uganda, by Issa Sikiti da Silva: Uganda’s natural resources continue to be plundered.Cigar smoke and mirrors, by James Bloodworth: Cuba’s propaganda must not blight our perception of it.

Denialism is not protected speech, by Oz Katerji: Should challenging facts be protected speech?

Permissible weapons, by Peter Hitchens: Peter Hitchens responds to Nerma Jelacic on her claims for disinformation in Syria.

No winners in Israel’s Ice Cream War, by Jo-Ann Mort: Is the boycott against Israel achieving anything?

Better out than in? By Mark Glanville: Can the ancient Euripides play The Bacchae explain hooliganism on the terraces?

Russia’s Greatest Export: Hostility to the free press, by Mikhail Khordokovsky: A billionaire exile tells us how Russia leads the way in the tactics employed to silence journalists.

Remembering Peter R de Vries, by Frederike Geeerdink: Read about the Dutch journalist gunned down for doing his job.

A right royal minefield, by John Lloyd: Whenever one of the Royal Family are interviewed, it seems to cause more problems.

A bulletin of frustration, by Ruth Smeeth: Climate change affects us all and we must fight for the voices being silenced by it. Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

The man who blew up America, by David Grundy: Poet, playwright, activist and critic Amiri Baraka remains a controversial figure seven years after his death.

Suffering in silence, by Benjamin Lynch and Dr Parwana Fayyaz The award-winning poetry that reminds us of the values of free thought and how crucial it is for Afghan women.

Heart and Sole, by Mark Frary and Katja Oskamp: A fascinating extract gives us an insight into the bland lives of some of those who did not welcome the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Secret Agenda, by Martin Bright: Reforms to the UK’s Official Secret Act could create a chilling effect for journalists reporting on information in the public interest.

24 Sep 2021 | Bosnia, China, News, Turkey, Volume 50.03 Autumn 2021 Extras

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”117556″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]Almost three decades ago, some three million books and countless artefacts went up in flames when Sarajevo’s National and University Library – inside the Vijecnica (city hall) – was burned to the ground. The destruction of the Vijecnica at the beginning of the war was a symbol for one of the aggressor’s main objectives – silencing the soul of the city and crushing the cultural identity of an entire society.”

So said Dunja Mijatović, the current Council of Europe commissioner for human rights, who was born in Sarajevo when it was part of Yugoslavia.

Just weeks before the anniversary of the burning of the library on 25 August 1992, Mijatović spoke to Index about its symbolism and what its destruction was meant to achieve.

She quoted Heinrich Heine’s play, Almansor: “Where they burn books they will also, in the end, burn people.”

Libraries and archives have been targets for centuries, and the reason is always the same: it’s about taking away knowledge and stifling free thinking.

Libraries are, and have always been, symbols of freedom – the freedom to think and learn and find documents and books to debate and discuss.

Throughout history, when authoritarians take power and seek to control thought and behaviour, they either lock up libraries or destroy the manuscripts and books inside them.

The Serbian forces who burned the Sarajevo library were seeking to obliterate evidence of Bosnia and Herzegovina’s existence as a successful multicultural and multi-ethnic state. The documents they burned told a different history from the one that the army leaders wanted to portray.

Omar Mohammed, who reported as Mosul Eye on the Isis occupation of his city in Iraq, risked his life to blog anonymously about the occupiers’ wish to destroy books as well as to execute people as they sought to repress the population.

Mohammed told Index that it was not just the university library that was destroyed in Mosul, but it was the one that was reported on the most.

Many other libraries, even private collections, were wiped out. “The only possible reason is because knowledge is power,” he said. “Once you prevent people from accessing knowledge then you will have full control over them.”

Like many other scholars who have delved into the history of libraries, Mohammed understands that it is not about the buildings themselves.

“They don’t want people to have this access because they know if people write the history, it will be completely different from the one they wanted it to be,” he said.

Targeting libraries sends out a powerful message to scholars, historians and scientists, he added.

“When they see that such people are able to totally target the libraries, that they are literally able to destroy everything, it’s a manifestation of brutality.”

Today, Richard Ovenden, the most senior librarian at the Bodleian libraries at the University of Oxford, is worried about libraries in Turkey being closed under pressure from the government of president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

According to some sources, at least 188 libraries were closed there between 2002 and 2020.

Ovenden’s book, Burning the Books, looks at the history of the intentional destruction of knowledge. He was recently contacted by a Turkish student, who said: “I’ve just read your book and I want you to know how bad it is in Turkey, because libraries are being destroyed. And all the things that you write about are true in Turkey today.”

Ovenden said: “There is an absolutely authoritarian control over knowledge. Attacks on knowledge are being exercised by the authoritarian leader of Turkey right now. It is the ability for the population to generate their own ideas and to come up with their own thoughts that some governments, some authoritarian powers, some dictators and rulers do not like.”

When dictatorships seek to establish that certain minorities don’t exist, or haven’t lived somewhere, getting rid of the documentary evidence is very convenient.

Archives that establish the existence of Uighurs in China and Muslims in parts of India also look like targets.

Ovenden feels that what is fantastically important about libraries is that they “preserve the past thoughts and ideas of human beings so they’re parts of that evidence base”.

He added: “They’re also disseminating institutions [where] you can borrow the books, you can come and take those ideas away and write other books about them, or pamphlets, or newspaper articles, or whatever it is.”

Governments around the world are failing to protect libraries as a resource, sometimes by withdrawing or drastically reducing funding.

In the UK, almost 800 libraries closed between 2010 and 2019, and a major campaign kicked off in Australia this year to save the national archives.

Michelle Arrow, professor of history at Macquarie University in Sydney, argued in April that if funding cuts were not reversed, irreplaceable audio-visual collections would fall apart. After a public campaign, the national government has delivered some extra funding, but this has not solved all the archives’ problems.

She told Index that with a reduction in staff of almost 25% since 2013, more staff would be needed to deal with the large backlog of requests to view archived material.

She said the archives contained “unique records, and they touch almost every Australian: it is a democratic archive, a collection of ordinary people’s records, rather than famous or renowned Australians”.

While some countries are seeing numerous library closures due to financial or other threats, there are new defenders coming to light. In the coastal city of Santa Cruz in California, there’s a massive investment in upgrades to current libraries, and new ones are opening over the next two years.

Santa Cruz mayor Donna Meyers told Index: “In California, we just tend to believe in public institutions. We believe that public education, public libraries, all of that, lead to a better community, lead to a more informed society.”

Santa Cruz residents passed a special tax – by 78% of the vote – to pay for investment in the libraries which, Meyers says, is a sign of how committed the community is to libraries being around for future generations.

Back in Sarajevo, Mijatović can see the new library that rose from the ashes of the Vijecnica from her terrace.

She said: “One hopes that the soul and the people of Sarajevo will recover and that new generations will hopefully enjoy this magnificent symbol of Sarajevo and, more importantly, live in peace.”

Library destruction in recent history

1914: German troops destroy the library of the Catholic University of Louvain

1939: The Great Talmudic Library in Lublin is destroyed by the Nazis

1966-76: Chairman Mao destroys libraries across China as part of the Cultural Revolution

1976-79: The Khmer Rouge deliberately destroy libraries across Cambodia, including the Phnom Penh national library

2013: Islamic troops set fire to the library in Timbuktu, Mali

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

26 Jul 2021 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021

Index’s new issue of the magazine looks at the importance of whistleblowers in upholding our democracies.

Featured are stories such as the case of Reality Winner, written by her sister Brittany. Despite being released from prison, the former intelligence analyst is still unable to speak out after she revealed documents that showed attempted Russian interference in US elections.

Playwright Tom Stoppard speaks to Sarah Sands about his life and new play title ‘Leopoldstatd’ and, 50 years on from the Pentagon Papers, the “original whistleblower” Daniel Ellsberg speaks to Index .

by Index on Censorship | 26 Jul 21 | Africa, Bosnia, Burma, China, Europe and Central Asia, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Magazine, Magazine Contents, Slapps, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021, Volume 50.02 Summer 2021 Extras | 0 Comments

Index's new issue of the magazine looks at the importance of whistleblowers in upholding our democracies. Featured are stories such as the case of Reality Winner, written by her sister Brittany. Despite being released from prison, the former intelligence analyst is...

20 Jun 2021 | Italy, Media Freedom, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, Wales

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image="116924" img_size="full" add_caption="yes"][vc_column_text]In celebration of one of football’s biggest international tournaments, here is Index’s guide to the free speech Euros. Who comes out on top as the nation with the worst record on free speech?

It’s simple, the worst is ranked first.

We start today with Group A, which plays the deciding matches of the group stages today.

1st Turkey

Turkey’s record on free speech is appalling and has traditionally been so, but the crackdown has accelerated since the attempted – and failed – military coup of 2016.[1][2]

The Turkish government, led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has attacked free speech through a combination of closing down academia and free thought and manipulating legislation to target free speech activists and the media. He has also ordered his government to take over newspapers to control their editorial lines, such as the case with the newspaper Zaman, taken over in 2014.[3]

Some Turkish scholars have been forced to inform on their colleagues[4] and Erdoğan also ordered the closing down of the prominent Şehir University in Istanbul in June 2020[5].

But it is manipulation of legislation that is arguably the arch-weapon of the Turkish government.

A recent development has seen the country use Law 3713, Article 314 of the Turkish Penal Code and Article 7 of the Anti-Terror Law to convict both human rights activists and journalists.

As of 15 June this year, a total of 12 separate cases of under Law 3173[6] have seen journalists currently facing prosecution, merely for being critical of Turkey’s security forces.

This misuse of the law has caused worldwide condemnation from the European Union, the United Nations and the Council of Europe, among many others[7].

Misuse of anti-terrorism legislation is a common tactic of oppressive regimes and is reflective of Turkey’s overall attitude towards freedom of speech.

Turkey also has a long history of detaining dissenting forces and is notorious for its dreadful prison conditions. Journalist Hatice Duman, for example, has been detained in the country since 2003[8]. She has been known to have been beaten in prison.[9]

Leading novelists have also been attacked. In 2014, the pro-government press accused two authors, Elif Shafak and Orhan Pamuk were accused of being recruited by Western powers to be critical of the government.[10]

Every dissenting voice against the government in Turkey is under scrutiny and authors, journalists and campaigners easily fall foul of the country’s disgraceful human rights record.

With a rank of 153rd on Reporters Without Borders’ 2021 World Press Freedom Index, it is also the worst-placed team in the tournament in this regard.

2nd Italy

Freedom of speech in Italy was enshrined in the 1948 constitution after the downfall of fascist dictator Benito Mussolini in 1945. However, a combination of the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, oppressive legislation and violent threats to journalists means that its record is far from perfect.

Slapps (strategic lawsuits against public participation) are used by governments and big corporations as a form of intimidation against journalists and are common in Italy.

Investigative journalist Antonella Napoli told Index of the difficulty journalists such as her face due to Slapps. She herself is facing a long-running suit, which first arose in 1998. She will face her next hearing on the issue in 2022[11].

She said: “We investigative journalists are under the constant threat of litigation requires determination to continue our work. A pressure that few can endure.”

“When happen a similar case you feel gagged, tied, especially if you are a freelance journalist. If you get your hands on big news about a public figure with the tendency to sue, you’ll think twice. I have never stopped, but many give up because they fear consequences that they can’t afford.”

Italy bore the brunt of the early stages of the pandemic in Europe. Often, when governments experience nationwide crises, they use certain measures to implement restrictive legislation that cracks down on journalism and free speech, inadvertently or not.

The decree, known as the Cura Italia law, meant that typical tools for journalists, or any keen public citizen, such as Freedom of Information requests were hard to come by unless deemed absolutely necessary.

Aside from Covid-19 restrictions, Italy continues to have a problem with the mafia. There are currently 23 journalists under protection in the country.[12]

3rd Wales

Wales is very much subject to the mercy of Westminster when it comes to free speech

Arguably, the most concerning development is the Online Safety Bill (also known as ‘online harms’), currently in its white paper stage.

While there are, sadly, torrents of online abuse, this attempt to regulate speech online is concerning.

The draft bill contained language such as “legal but harmful” means there would be a discrepancy between what is illegal online, versus what would be legal offline and thus a lack of consistency in the law regarding free speech.

The world of football recently took part in an online social media blackout, instigated in part by Welsh club Swansea City on 8 April[13], following horrific online racial abuse towards their players.

Swansea said: “we urge the UK Government to ensure its Online Safety Bill will bring in strong legislation to make social media companies more accountable for what happens on their platforms.”[14]

But the boycott was criticised with some, including Index, concerned about the ramifications pushing for the bill could have.

In 2020, Index’s CEO Ruth Smeeth explained what damage the legislation could cause: “The idea that we have something that is legal on the street but illegal on social media makes very little sense to me.”[15]

4th Switzerland

Switzerland has an encouraging record for a country that only gave women the vote in 1971.

They rank 10th on RSF’s World Press Freedom Index and have, generally speaking, a positive history regarding free speech and freedom of the press.

But a recent referendum may prove to be an alarming development.

Frequently, where there may be unrest or a crisis in a country, government’s use anti-terrorism laws to their own advantage. Voices can be silenced very quickly.

On 13 June, Switzerland voted to give the police detain people without charge or trial[16] under the Federal Law on Police Measures to Combat Terrorism.

Amnesty International Switzerland’s Campaign Director, Patrick Walder said the measures were “not the answer”.

“Whilst the desire among Swiss voters to prevent acts of terrorism is understandable, these new measures are not the answer,” he said. “They provide the police with sweeping and mostly unchecked powers to impose harsh sanctions against so-called 'potential terrorist offenders' and can also be used to target legitimate political protest.”

“Those wrongly suspected will have to prove that they will not be dangerous in the future and even children as young as 12 are at risk of being stigmatised and subjected to coercive measures by the police.”

56.58 per cent came out in support of the measures.[17]

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jW_c30hwXTM&ab_channel=Vox

[2] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306422020917614

[3] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/03/turkey-fears-of-zaman-newspaper-takeover/

[4] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306422020917614

[5] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306422020981254

[6] https://rsf.org/en/news/turkey-using-terrorism-legislation-gag-and-jail-journalists

[7] https://stockholmcf.org/un-calls-on-turkey-to-stop-misuse-of-terrorism-law-to-detain-rights-defenders/

[8] https://cpj.org/data/people/hatice-duman/

[9] https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2021/01/the-desperate-situation-for-six-people-who-are-jailednotforgotten/

[10] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/dec/12/pamuk-shafak-turkish-press-campaign

[11] https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Areas/Croatia/Croatia-and-Italy-the-chilling-effect-of-strategic-lawsuits-197339

[12] https://observatoryihr.org/iohr-tv/23-journalists-still-under-police-protection-in-italy/

[13] https://twitter.com/SwansOfficial/status/1380113189447286791?s=20

[14] https://www.swanseacity.com/news/swansea-city-join-social-media-boycott

[15] https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2020/09/index-ceo-ruth-smeeth-speaks-to-board-of-deputies-of-british-jews-about-censorship-concerns/

[16] https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/freedom-of-expression--universal--but-not-absolute/46536654

[17] https://lenews.ch/2021/06/13/swiss-vote-in-favour-of-covid-laws-and-tougher-anti-terror-policing-13-june-2021/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

Cover of Index on Censorship Autumn 2021 (50-3)[/caption]

Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]

Credit: Gregory Maassen/Alamy[/caption]