16 Jun 2020 | Magazine, Magazine Editions, Volume 49.02 Summer 2020

Journalist

Issa Sikiti da Silva is an award-winning freelance journalist who has traveled extensively across Africa. Born in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, he has lived in South Africa and worked as a foreign correspondent in West Africa. His work has been published in nearly 40 media outlets

Actor and playwright

Katherine Parkinson is a Bafta-award winning English actress. She has appeared in several television series, including The IT Crowd and Humans. She has also appeared in such films as How to Lose Friends & Alienate People and The Boat That Rocked, as well as on stage in various high profile West End shows. In 2019 Parkinson’s debut work as a playwright, Sitting, had its London premiere, after a month-long run at the Edinburgh Fringe

Playwright

David Hare is a playwright and film-maker. He has written over thirty stage plays which include Plenty and Pravda (with Howard Brenton). For film and television, he has written nearly thirty screenplays which include Licking Hitler, The Hours, The Reader and Denial. In a millennial poll of the greatest plays of the 20th century, five of the top 100 were his

14 May 2020 | Covid 19 and freedom of expression, News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

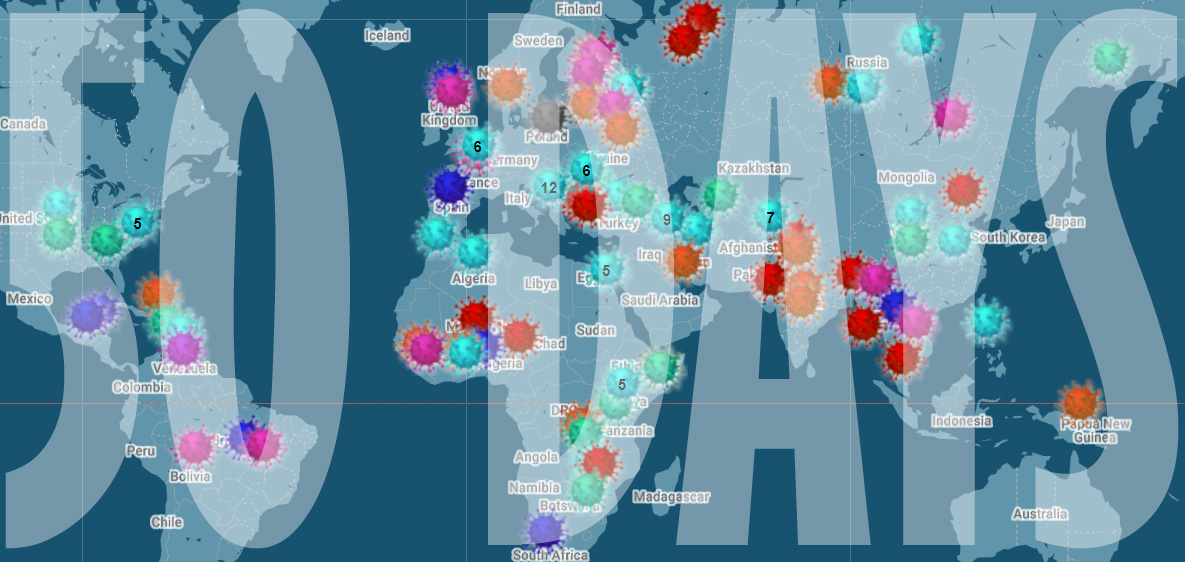

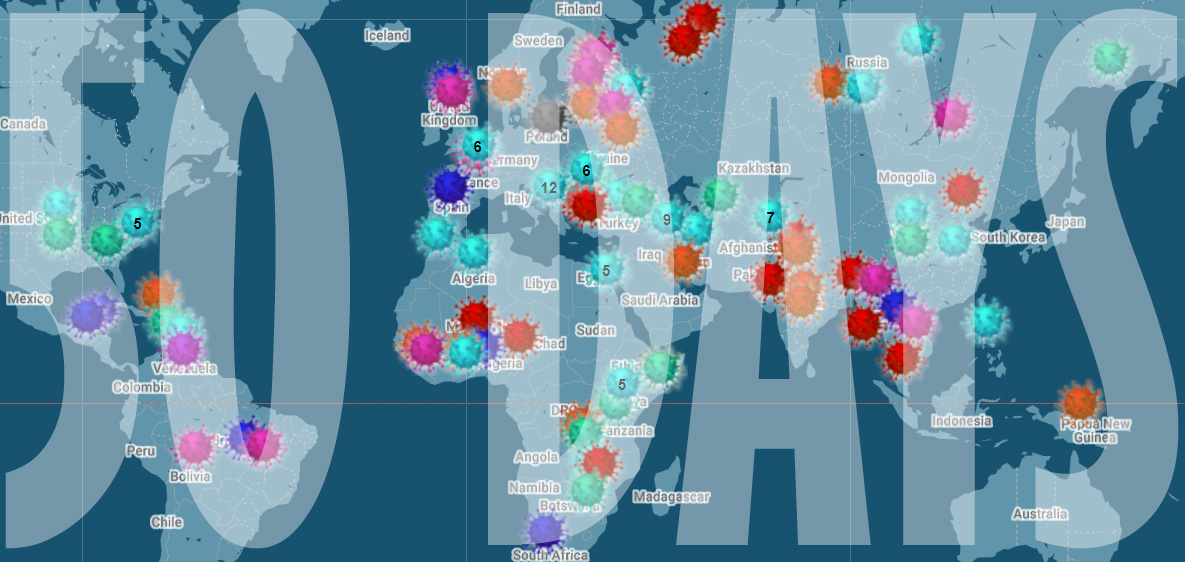

As we mark 50 days since we first started collating attacks on media freedom related to the coronavirus crisis, we’re horrified by the number of attacks we have mapped – over 150 in what is ultimately a short period of time.

We know that in times of crisis media attacks often increase – just look at what happened to journalists after the military coup in Egypt in 2013 and the failed coup against Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey in 2016. The extent of the current attacks, in democratic as well as authoritarian countries, has been a shock.

Our network of readers, correspondents, Index staff and our partners at the Justice for Journalists Foundation have helped collect the more than 150 reports media attacks.

But these incidents are likely to be the very tip of the iceberg. When the world is in lockdown, finding out about abuses of power is harder than ever. Journalists are struggling to do their job even before harassment. How many more attacks are happening that we don’t yet know about? It’s a scary thought.

Rachael Jolley, editor-in-chief of Index on Censorship, said: “We are alarmed at the ferocity of some of the attacks on media freedom we are seeing being unveiled. In some states journalists are threatened with prison sentences for reporting on shortages of vital hospital equipment. The public need to know this kind of life-saving information, not have it kept from them. Our reporting is highlighting that governments around the world are tempted to use different tactics to stop the public knowing what they need to know.”

Index is alarmed that the attacks are not coming from the usual suspects. Yes, there have been plenty of incidents reported in Russia and the former Soviet Union, Turkey, Hungary and Brazil. At the same time there have been many incidents in countries you would not expect to see – Spain, New Zealand, Germany and the UK.

The most common incident we have recorded on the map are attacks on journalists – whether physical or verbal – and cases where reporters have been detained or arrested. There have been more than 30 attacks on journalists, with the source of many of these being the US President Donald Trump. He has a history of being combative with the press and decrying fake news even where the opposite is the case and the crisis has seen a ramped up attempt at excluding the media. During the crisis, he has refused to answer journalists’ questions, attacked the credentials of reporters and walked out from press conferences when he doesn’t like the direction they are taking.

We have also seen reporters and broadcasters detained and charged just for trying to tell the story of the crisis, including Dhaval Patel, editor of the online news portal Face of Nation in Gujarat, Mushtaq Ahmed in Bangladesh and award-winning investigative journalist Wan Noor Hayati Wan Alias in Malaysia.

Since we started the mapping project, we have highlighted other specific trends. Orna Herr has written about how coronavirus is providing pretext for Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to increase attacks on the press and Muslims. Jemimah Steinfeld wrote about how certain leaders are dodging questions while we have also looked at how freedom of information laws are being suspended or deadlines for information extended.

Although the map does not tell the whole story it does act as a record of these attacks. When this crisis is finally all over, it will allow us to ask questions about why these attacks happened and to make sure that any restrictions that have been introduced are reversed, giving us back our freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_btn title=”Report an incident” shape=”round” color=”danger” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fforms.gle%2Fhptj5F6ZvxjcaGLa7|||” css=”.vc_custom_1589455005016{border-radius: 5px !important;}”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

29 Apr 2020 | News

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Attacks on press freedom in Europe are at serious risk of becoming a new normal, 14 international press freedom groups and journalists’ organisations including Index on Censorship warn today as they launch the 2020 annual report of the Council of Europe Platform to Promote the Protection of Journalism and the Safety of Journalists. The fresh assault on media freedom amid the Covid-19 pandemic has worsened an already gloomy outlook.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

The report analyses alerts submitted to the platform in 2019 and shows a growing pattern of intimidation to silence journalists in Europe. The past weeks have accelerated this trend, with the pandemic producing a new wave of serious threats and attacks on press freedom in several Council of Europe member states. In response to the health crisis, governments have detained journalists for critical reporting, vastly expanded surveillance and passed new laws to punish “fake news” even as they decide themselves what is allowable and what is false without the oversight of appropriate independent bodies.

These threats risk a tipping point in the fight to preserve a free media in Europe. They underscore the report’s urgent wake-up call on Council of Europe member states to act quickly and resolutely to end the assault against press freedom, so that journalists and other media actors can report without fear.

Although the overall response rate by member states to the platform rose slightly to 60 % in 2019, Russia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan – three of the biggest media freedom violators – continue to ignore alerts, together with Bosnia and Herzegovina.

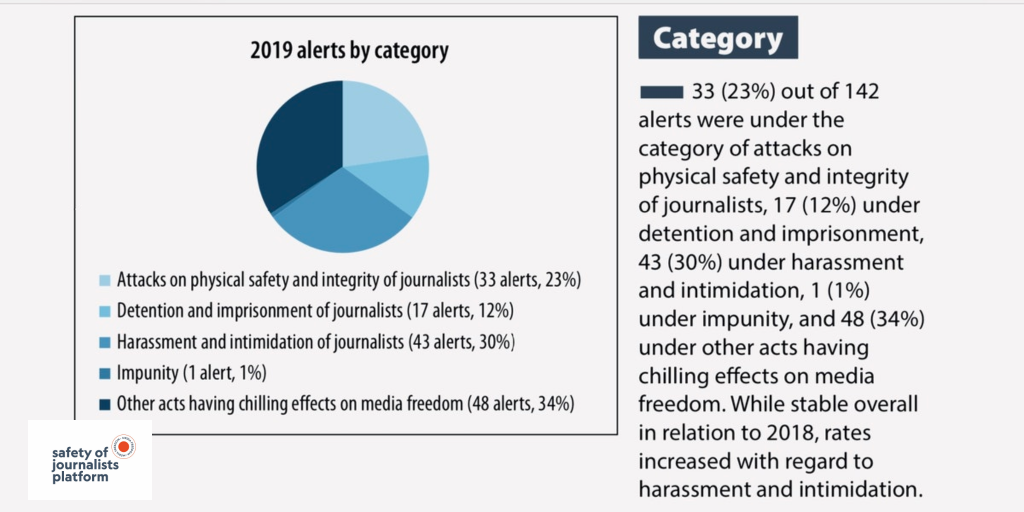

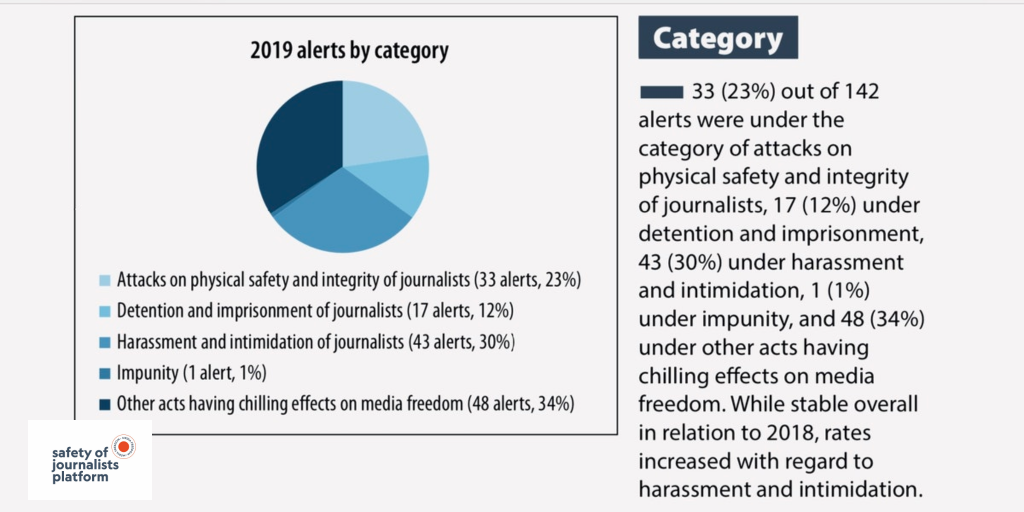

2019 was already an intense and often dangerous battleground for press freedom and freedom of expression in Europe. The platform recorded 142 serious threats to media freedom, including 33 physical attacks against journalists, 17 new cases of detention and imprisonment and 43 cases of harassment and intimidation.

The physical attacks tragically included two killings of journalists: Lyra McKee in Northern Ireland and Vadym Komarov in Ukraine. Meanwhile, the platform officially declared the murders of Daphne Caruana Galizia (2017) in Malta and Martin O’Hagan (2001) in Northern Ireland as impunity cases, highlighting authorities’ failure to bring those responsible to justice. Only Slovakia showed concrete progress in the fight against impunity, indicting the alleged mastermind and four others accused of murdering journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová.

At the end of 2019, the platform recorded 105 cases of journalists behind bars in the Council of Europe region, including 91 in Turkey alone. The situation has not improved in 2020. Despite the acute health threat, Turkey excluded journalists from a mass release of inmates in April 2020, and second-biggest jailer Azerbaijan has made new arrests over critical coverage of the country’s coronavirus response.

2019 saw a clear increase in judicial or administrative harassment against journalists, including meritless SLAPP cases, and spurious and politically motivated legal threats. Prominent examples were the false drug charges filed against Russian investigative journalist Ivan Golunov and the continued imprisonment of journalists in Ukraine’s Russia-controlled Crimea. The Covid-19 crisis has strengthened officials’ tools to harass journalists, with dangerous new “fake news” laws in countries such as Hungary and Russia that threaten journalists with jail for contravening the official line.

Other serious issues identified by 2019 alerts included expanded surveillance measures threatening journalists’ ability to protect their sources, including in France, Poland and Switzerland, as well political attempts to “capture” media through ownership and market manipulation, most conspicuously of all in Hungary. These threats, too, are exacerbated by the actions taken by several governments under the health crisis, which further include arbitrary limitations on independent reporting and on journalists’ access to official information about the pandemic.

Jessica Ní Mhainín, Index’s policy research and advocacy officer, says, “There is a growing pattern of intimidation aimed at silencing journalists in Europe. The situation in Eastern Europe – especially in Hungary, Poland, and Bulgaria – is particularly concerning. But the killing of Lyra McKee shows that we cannot take the safety of journalists for granted anywhere – not even in countries that are seen to be safe for journalists. This report provides an opportunity for us all to come to grips with the serious situation that is facing European media and to remind ourselves of the vital role that the media play in holding power to account.”

Index and the other platform partners call for urgent scrutiny of action taken by governments to claim extraordinary powers related to freedom of expression and media freedom under emergency legislation that are not strictly necessary and proportionate in response to the pandemic. Uncontrolled and unlimited state of emergency laws are open to abuse and have already had a severe chilling effect on the ability of the media to report and scrutinise the actions of state authorities.

While the platform welcomes an increased focus on press freedom by European institutions, including both the Council of Europe and European Union institutions, the ongoing crisis demands more urgent and stringent responses to protect media freedom and freedom of expression and information, and to support the financial sustainability of independent professional journalism. In the age of emergency rule, protecting the press as the watchdog of democracy cannot wait.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

21 Apr 2020 | Magazine, News, Volume 49.01 Spring 2020

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Keeping our heads down can mean that hard-won rights can easily be lost. Sometimes we choose to stay quiet, but often we are complicit without realising, says Rachael Jolley” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_single_image image=”113251″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“It is easy to part with or give away great privileges, but hard to be gained if once lost,” said Quaker William Penn, who went on to establish the state of Pennsylvania in the USA.

Far more recently, another wise man, former Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales Lord Judge, said: “There are still many countries in the world where what we happily call our rights remain privileges waiting to be won and entrenched.”

These thoughts are the cornerstones of the theme of this issue – the idea that we can give away our rights if we do not stand up for them.

We can be complicit in letting them erode if we feel they are not important enough or let other things take precedence, and many are willing to give away freedom for security.

The Merriam Webster dictionary tells us that the root of the English word “complicit” comes from the Latin word “complicare”, meaning “to fold together”, and that it has evolved over time into meaning helping to do wrong or to commit a crime in some way – in other words, allowing ourselves to be folded into a bad idea.

In allowing ourselves to be complicit, we potentially allow those in power to take away some of our rights forever.

As Lord Judge also points out in his book The Safest Shield, we should be careful never to assume that liberties, rights and justice can be taken for granted.

Complicity is our theme for today because, in 2020, there are multiple powers that like us to give things away – our privacy, our knowledge and even our power to say no. They try to get us to fold into their purpose, to agree it and let them move forward.

It comes at us in many forms.

Many of us are complicit in giving away lots of information about ourselves, such as our contacts and photo albums from our phones. We do this in exchange for free use of software apps – Facebook or Google Maps, for instance.

We do a deal with their owners that they will let us use their stuff, and not charge us, but all along, deep down, we probably guess there is some pay-off.

We know there’s no such thing as a free lunch, so why would there be free email or free software? The answer is: there isn’t. There is a price to pay – you exchange your knowledge and contacts for that which is “free”.

And, as Mark Frary investigates on page 31, taking some decisions – such as being logged in all the time – means you are giving away more than you might imagine.

Frary tracks how much information Google is storing about him and his movements, and realises that it knows 700 places which he has visited in the past six years. That’s a lot of knowledge about him, his movements and where he might be going.

It doesn’t take much imagination to think back to a time when that would be a treasure trove to a government wanting to know more about its citizens because it wanted to prevent them having information, passing it to others and knowing what was going on.

Let’s take the Latin American dictatorships of the 1970s and 1980s, for instance, where journalists and many others were “disappeared” for asking the wrong questions.

What if that kind of information had been available to those governments? What extra power would it have given them to track down dissenters and to send in the police?

Shift forward in time to Venezuela today, from where Stefano Pozzebon reports for us on why the media and activists feel afraid. Threats and imprisonment are being used by the authoritarians in charge of this troubled nation to silence those who disagree with them.

And that government could try to access individuals’ whereabouts from Google Maps simply by putting in a request to Google. The company doesn’t always hand over information to governments which request it, but many times it does. Imagine for a moment what that might feel like.

Pozzebon said: “For those who don’t want to join the almost five million Venezuelans who have already left, not saying anything about anything becomes the only way to cope.”

When we are afraid we are most at risk from the pressure that others might place on us not to speak out or criticise. We can be complicit in attempts by the powerful to change society and remove those rights that Penn set out.

Of course, acting out of fear is understandable. It is easy for those far away who are not risking their lives, or those of their families, to say: “Oh you must do this, or stand up for that.” It is not so easy to do that once you know what, and whom, you put at risk.

This desire to quiet your anger and put it away until a less dangerous time is something that most humans can understand.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fas fa-quote-left” size=”xl”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The petition said she demanded the imprisonment of scholars who had signed a ‘Peace Petition’. The thing was, she didn’t” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

That’s why Kaya Genç’s article from Turkey is so important. In it he describes the moment that changed one academic’s attitude dramatically. The name of Anıl Özgüç, a professor of medicine at Istanbul’s Aydın University, was added to a pro-government petition without her knowledge. The petition said she demanded the imprisonment of scholars who had signed a “Peace Petition”. The thing was, she didn’t.

And by that action, her attitude – which had been to keep quiet and hope for the best – changed.

She had reached her tipping point and she was no longer prepared to shut up: it was a step too far to take her name from her. Like John Procter in The Crucible, giving up her name was too much.

Suddenly she put aside her fears and spoke up. She is now an open critic of the government’s attempts to restrict academic freedom.

This chimes with new research from Jennifer Pan, at Stanford University, who looks at repression in authoritarian countries. Her research found that arrests of outspoken activists in Saudi Arabia had the effect of silencing the individuals but, surprisingly, did not deter others from speaking out. In fact, it motivated more people to criticise the government and the monarchy, and stepped up calls for change.

So while outsiders might expect the opposite to be true – that people would be cowed – Pan’s research shows that there is a tipping point and it can prompt more outspoken calls for change.

Complicity is not an easy topic. We should all be able to see there are sometimes reasons for not challenging the powerful, and times when it would be understandable to feel afraid or at risk.

Many around the world take that responsibility very seriously, and choose to make brave choices – even when it might put them in danger. It is these people whom Index often profiles, and we are in awe of those who can be incredibly brave when the odds are stacked against them.

Complicity is a challenge for us constantly, and in small and large ways we will be confronted by it all our lives. The question is: what is our response?

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The piece is part of the 2020 spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine. Buy a copy or subscribe here.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Why and when we chose to censor ourselves and give away our privacy” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]The spring 2020 Index on Censorship magazine looks at how we are sometimes complicit in our own censorship[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”112723″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]