Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Yavuz Baydar (YouTube)

It’s 2016. Turkey is in a state of emergency after the failed coup against the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Journalists like Yavuz Baydar found themselves more at risk than ever before. He had a decision to make: leave Turkey while he still could, or stay and potentially become part of the more than 160,000 journalists, protesters, dissidents and political pundits have since been jailed.

Baydar is an accomplished journalist with a career that spans four decades. In addition to his journalism roles, he was a co-founder of the non-profit P24, Platform for Independent Journalism which acts as an example of editorial independence in the Turkish press. He is the recipient of the 2014 Special Award of the European Press Prize (EPP) for excellence in journalism and in the same year completed an extensive research paper on self-censorship, corruption of ownership in Turkish media, state oppression and threats over journalism in Turkey during his Shorenstein Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School of Government. In 2017 he was awarded the Morris B Abram Human Rights Award by UN Watch. He has worked with Süddeutsche Zeitung, the Guardian, Huffington Post, Al Jazeera, The New York Times, and Index on Censorship, even his regular opinion columns for the Turkish dailies Today’s Zaman, Bugün and Özgür Düşünce. In early February 2018, Baydar was awarded the prestigious ‘Journalistenpreis’ by the Munich-based SüdostEuropa Gesellschaft.

He decided to leave Turkey for France.

Two years later on 25 June 2018, Erdoğan was re-elected president with 53% of the ballot to his closest rival Muharrem Ince’s 31%. Under Turkey’s new constitution, Erdoğan has been given autocratic powers that enable him to appoint ministers and vice-presidents, call for a state of emergency and intervene directly in the rule of law.

He keeps in touch with the status of press freedom in Turkey in his ‘Gazette’ which acts as a hosting site for curated links to the news articles of the day. In his latest endeavor, Baydar is in managing editor at Ahval. He took some time to answer some questions from Index on Censorship’s Nicole Ntim-Addae.

Index: What makes you such an ardent supporter of media freedom?

Baydar: My education. I had the great chance of being enrolled at the prestigious School of Journalism at Stockholm University. It was a wonderfully open and generous environment. There, as our dean used to say, ‘we learned the basics of the social role of the profession’. We learned how much bravery it demands. It taught us to be free of any dogma, and act fearlessly against the holders of power. I owe a lot to the school, but also to Swedish Radio and TV Corporation. Then, also the BBC World Service was important for the formation.

Index: Where were you when you made the decision to leave? What was the trigger?

Baydar: I was at home. It was a very intense night. And in the morning, after a short sleep, I assessed the situation and concluded that no matter with the outcome of the putsch, we the journalists would be declared the scapegoats and forced to pay the price. In any case, already then, Turkey had turned into hell for journalism.

Index: How is France different than Turkey? Do you feel settled there?

Baydar: Excellent environment, has always been for its commitment to freedom. It was perhaps there for the so called Young Turks, who were at the opposition to Sultan 120 years ago, had settled there. As I am now.

Index: What does you hope for Ahval to accomplish?

Baydar: Good, honest journalism. Strong coverage for facts, especially economy. That it accurately, fairly informs Turkish readers, who are stripped of independent sources. Also the international audience gets a comprehensive picture of the reality in the country. Our backbone is the critical minds. We are not an opposition outlet; we are critical. It is the essence of journalism.

Index: How difficult has it been to be away from home?

Baydar: For me, not much. I lived abroad long enough, so I am accustomed to it. For some of the staff, it may be difficult, because many of them experience the exile for the first time.

Index: Considering that Erdoğan won the election, and was awarded additional powers by and was awarded additional powers by the referendum, safe to return home soon?

Baydar: No. It is an unfree environment. Has no space for independent criticism. And the rule of law has been suspended over there. We will have to wait some time, before conditions change.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship documents threats to media freedom in Europe through a monitoring project and campaigns against laws that stifle journalists’ work. We also publish an award-winning magazine

Learn more about our work to protect press freedom.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Global Journalist / Project Exile” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”22142″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

İdris Sayılgan’s father Ramazan, mother Sebiha and sisters Tuğba and İrem pose in the meadow where the family comes the summers to breed their cattle (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

“Don’t forget to take pills for nausea,” says İdris Sayılgan’s younger sister, Tuğba, combining her knowledge as a fifth-year pharmacy student and the innate kindness of a host. Together with a colleague, we were about to take the bumpy road to follow in the jailed Kurdish journalist’s footsteps to his family’s village near the eastern Turkish city of Muş. Sayılgan had spent his summer holidays helping his father, a herdsman or “koçer” in Kurdish (literally meaning “nomad”), breeding cattle and goats. One of many Kurdish reporters imprisoned pending trial, Sayılgan has been behind bars for 21 months on trumped-up charges that have criminalised his journalistic work. His hard-working, close-knit family misses his presence dearly.

Heading south of Muş, to the fertile Zoveser mountains, the serpentine road proves Tuğba’s advice to be valuable. The asphalt pavement gives way to a narrow gravel road as we continue to zig-zag toward the southern flank of Zoveser, bordering Kulp in Diyarbakır province and Sason in Batman – two localities which used to be home to an important Armenian community before the Armenian Genocide in 1915. The many majestic walnut trees surrounding the road are a testament to that bygone era. We are told that they were all planted by Armenians before they fled.

The family village – Heteng to Kurds and İnardi to the Turkish state – witnessed another brutal eviction in more recent times. During the so-called dirty war of the 1990s, the Turkish military gave inhabitants a stark choice: either become village guards, armed and remunerated by the state to inform on the activities of militants belonging to the Kurdish insurrection, or leave. If they dared to refuse, a summary death awaited. İdris was just three-years-old when they came.

Left helpless and scared, many left. The family of Çağdaş Erdoğan, the Turkish photographer hotlisted by the British Journal of Photography who recently spent six months in prison on terror-related charges, was among them. Erdoğan scarcely remembers his childhood before his family moved to the western industrial city of Bursa. As a child, the painfully forced exile produced nightmares. He started imagining stories from patches of memories, believing they were real. Zoveser’s idyllic setting is haunted by the ghosts of a dark history brimming with atrocities.

The family guides the cattle to the pasture. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

As for İdris’ family, they have stayed in the Muş ever since, coming back only for breeding season. İdris used to accompany his father in guiding their cattle, during which time they would cover the 70 kilometres separating their farm near Muş to Heteng in three days. It’s a distance that we could only cover in two-and-a-half hours by vehicle. Once in Heteng, there’s still another 15 minutes on foot to the small meadow where the Sayılgans have set up camp next to a fresh stream.

İdris’ father, Ramazan Sayılgan, greets us with a warm embrace. He has a gentle look with soft and tired eyes. “Are you hungry?” he asks as we are invited to their tent. His wife, Sebiha, brings us milk and fresh kaymak cheese, a cream obtained from yoghurt, that she made herself, as well as milk. All of the children help the family during the breeding season. Ramazan can’t hide his pride when he recounts how well they are doing in their studies and how gifted they are. Unlike many parents in the region, he strived to send his nine children to school despite his meagre income. The nine brothers and sisters are close and often go the extra mile for each other.

İdris is the very picture of his father who, although sunburnt, is a little bit darker than him. He inherited the whiteness of his skin from his mother, whom he calls “the most beautiful woman on earth.” With them are the five youngest of the family. Involving herself in the conversation, eight-year-old Hivda sadly notices that she is the only one with olive skin, like her father. Ramazan Sayılgan is quick to comfort her. “You may be darker but you are such a beautiful, dark-skinned girl.” Hivda giggles cheerfully.

They work together and laugh together, but they also suffer together – like that fateful day when the police came for İdris.

A rifle to the head

It was early in the morning on 17 October, 2016, long before sunrise. The whole house was soundly asleep when their door was broken and ten riot police stormed inside.

“They were screaming ‘police, police!’ I told them: ‘Please be quiet, there is nothing in our house,’” Ramazan Sayılgan says, occasionally mixing Kurdish with his broken Turkish. “I was trying to calm them down and avoid trouble. Then I raised my head and saw that five people were on İdris. That’s when they kicked me in the head.”

İdris Sayılgan’s eight-year-old sister Hivda and 12-year-old Yunus. The family guides the cattle to the pasture. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

İdris tried to escape their clutches but fell to the floor. Police kicked him repeatedly while threatening him. The blows had left him bleeding. “They are killing İdris!” cried his sister İrem, who was 12 at the time. Police told the family to lie on the ground with their hands on their backs. They pointed a rifle at Ramazan and one of the journalist’s younger brothers, Yunus. “They even pointed two rifles at my head. They have no shame,” Yunus, who was ten-years-old at the time of the raid, says.

Normally, all raids should be filmed as a means of preventing abuse. “But they only started filming after they inflicted their brutality,” Ramazansays. Those who inflicted the beatings have enjoyed complete impunity. The family even saw the commander, a bald officer, when they went to vote during Turkey’s recent presidential elections.

In a written defence submitted to the court, İdris said that when he was brought to the hospital for a mandatory medical examination, doctors effectively turned a blind eye to police brutality by refusing to treat his injuries out of fear of repercussions from the police. To add insult to some very real injuries, İdris was transferred to a prison in Trabzon, some 500 kilometres north on the Black Sea coast, even though there is a prison in Muş. The family, who cannot afford a car, can only visit İdris on rare occasions. İdris was subjected to torture and strip searches after being transferred to Trabzon, where he is held in solitary confinement. “What I have been through is enough to prove that my detention is politically motivated,” the journalist has said in his defence statements.

“Journalism changed him”

After high school, İdris decided to abruptly end his studies and began working as a dishwasher. That, however, only lasted three months before he announced to his father that he wanted to prepare for the national university exams. “When he sets his mind on something, he always tries to do his best. He never puts it off. Nothing feels like it’s too much work for him,” his father tells us. “He didn’t study at first, but when he decided to do so, he devoted himself.”

İdris graduated from the journalism department at the Communication Faculty at the University of Mersin. He then returned to Muş and started to work for the pro-Kurdish Dicle News Agency (DİHA), which today operates under the name Mezopotamya Agency after DİHA was shuttered in 2016, and another iteration, Dihaber, in 2017, both on terror-related allegations. İdris was making a name for himself when he was arrested and now faces between seven-and-a-half and 15 years in prison on the charge of “membership in a terrorist organisation”.

“University and journalism changed him,” 18-year-old İsmail says. “He used to be more irritable. He has been much more cheerful since,” says İsmail, who picked up on his brother’s habit of whistling whenever he comes home. “İdris was even whistling in custody – to the extent that the police asked, ‘How can you remain so upbeat?’”

Sebihan Sayılgan, İdris’ mother, who he calls “the most beautiful woman on earth”. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

Tuğba remembers endless conversations at nights when İdris would recite poems by Ahmed Arif, a poet from Diyarbakır who was partly Kurdish. Yunus, meanwhile, complains that he only received İdris’ latest letter a full six weeks after it was sent. As for little Hivda, she whispers to us that she just sent him a poem she wrote.

Ramazan adds that İdris is loved by everyone who knows him. At 58, Ramazan continues to work hard but the family faces many adversities. Another son, 21-year-old Mehmet, has also been behind bars for two years. The eldest brother, Ebubekir, who became a math teacher, has been dismissed from the civil service for being a member of the progressive teachers’ union Eğitim-Sen. Ebubekir was well-known for improving the grades of all the students in his classes, but now that he has been forced out of his job, he has gone to Istanbul in an attempt to make ends meet. He will join them a week later to help them during the breeding season.

Since the state of emergency was imposed two years ago, village guards have become ever more self-assured. Like sheriffs in the wild west, they make their own rules. The Sayılgan family, who couldn’t come to the village for two years out of fear following the declaration of a state of emergency, alerts us that village guards often tip off authorities when they see strangers. “The driver of the shuttle is also a village guard,” we are warned. Indeed, we had already introduced ourselves to him as İdris’ friends from university, omitting to reveal our profession. During our trip back, we would tell him of our plans to catch a bus to Van when our real intention was to go north to Varto instead.

İdris Sayılgan’s 18-year-old İsmail who guided us to the meadow, with Hivda and Yunus in the background. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

Unlike most Kurdish provinces, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), well supported by the conservative voters, won the municipality of Muş in local elections, meaning the government hasn’t appointed trustees to force out elected Kurdish mayors as it has done in other Kurdish areas where it has lost. Police, accordingly, are extremely comfortable. The city abounds with plainclothes police and informants. No precaution is too little. Varto, a town with a majority of Alevis – who are a dissident religious minority with liberal and progressive beliefs – looks like a safer option to spend the night.

I get a sense of how hard it must be for a local Kurdish reporter to work in Muş. It means working behind the adversary’s lines while still living in one’s hometown. It also means never letting your guard down.

We take leave from the family, expressing our hope that İdris will be released at his next hearing on 5 October. “In three months and two days,” his father quickly notes. October will mark two years without his son – two years that a modest but resilient family has endeavoured to fight against state-sponsored injustice with goodwill and affection.

İdris Sayılgan’s father Ramazan, mother Sebiha and sisters Tuğba and İrem pose next to the tent where the family stays. (Credit: Özgün Özçer)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1532352402886-c28cce4d-6f18-8″ taxonomies=”1765, 1743″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

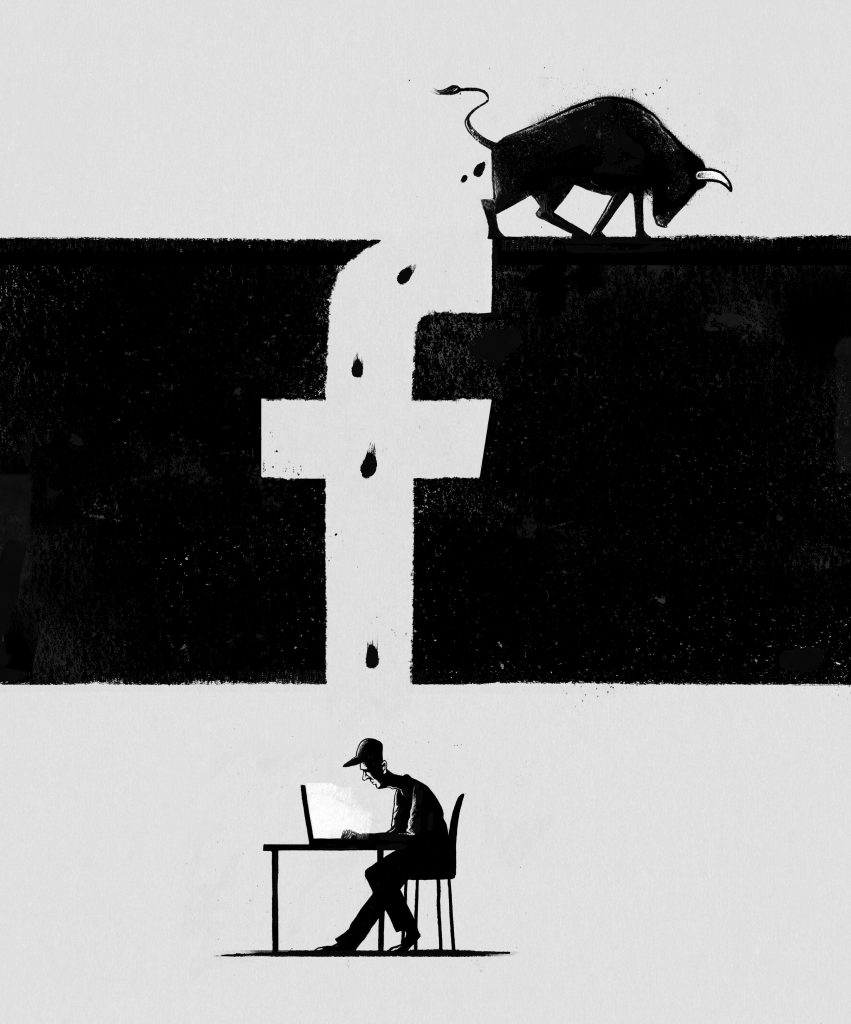

[vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” full_height=”yes” css_animation=”fadeIn” css=”.vc_custom_1531732086773{background: #ffffff url(https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/FinalBullshit-withBleed.jpg?id=101381) !important;}”][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Manipulating news and discrediting the media are techniques that have been used for more than a century. Originally published in the spring 2017 issue The Big Squeeze, Index’s global reporting team brief the public on how to watch out for tricks and spot inaccurate coverage. Below, Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley introduces the special feature” font_container=”tag:h2|text_align:left|color:%23000000″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Credit: Ben Jennings

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533808″][vc_custom_heading text=”There’s nothing new about fake news” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533808|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Andrei Aliaksandrau takes a look at fake news in Belarus[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”99282″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064227508532452″][vc_custom_heading text=”Fake news: The global silencer” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064227508532452|||”][vc_column_text]April 2018

Caroline Lees examines fake news being used to imprison journalists [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88803″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064229808536482″][vc_custom_heading text=”Taking the bait” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064229808536482|||”][vc_column_text]April 2017

Richard Sambrook discusses the pressures click-bait is putting on journalism[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”The Big Squeeze” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at multi-directional squeezes on freedom of speech around the world.

Also in the issue: newly translated fiction from Karim Miské, columns from Spitting Image creator Roger Law and former UK attorney general Dominic Grieve, and a special focus on Poland.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”88802″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”101526″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]

Naif Bezwan cannot pinpoint a certain moment in his life in which he decided to pursue academia. For Bezwan, rather, it has been a gradual process of situating his personal narrative within the context of his Kurdish community, within Turkey and within the world.

Bezwan, currently Honorary Senior fellow at UCL Department of Political Science, was born in Diyarbakir, one of the largest cities in southeastern Turkey. A focal point of conflicts between the Turkish government and insurgent groups, the city has a strong tradition of Kurdish liberation movement. Growing up, Bezwan heard the stories of previous generations, including those of his grandparents and relatives, about how they were repressed by the Turkish state. The trajectory of his academic interests was further shaped by his commitment to the universal human struggle for freedom and equality, as well as his determination for democratic reforms through rigorous inquiry. Several areas of his research and teaching expertise include Turkey’s policy towards Kurds and the Kurdish quest for self-rule.

It is not difficult to understand Bezwan’s motivation behind signing the Academics for Peace petition in January 2016. 1,128 academics from 89 universities in Turkey signed the petition, calling on the Turkish government to end its military operations in the Kurdish region and establish negotiations. This peaceful dissent emphatically rejected violence and yet, the signatories were detained and put under investigation. If found guilty of alleged terrorism charges, the petitioners could face between one and five years in prison.

After signing the petition with 37 colleagues from Mardin Artuklu University, Bezwan faced a disciplinary investigation in February 2016. A second investigation was launched just a few months later, in August 2016, after comments he made about the Turkish military incursion in Cerablus, Syria. This time, however, the consequences were even more severe, unjust and absurd.

The interview with the Turkish daily Evrensel was related to the core areas of his academic interests and expertise. Bezwan stressed the danger of using military forces at home and abroad in dealing with Kurdish rights and demands. He was immediately suspended from his position at Mardin Artuklu University, where he was teaching at the time, and completely dismissed through an emergency decree issued in September 2016.

Being deprived of teaching, conducting research or holding any public position, with the possible consequences of signing the Academics for Peace petition hanging over his head, Bezwan felt he had no choice but to leave his life in Turkey for London in November 2016. After almost a year of living in exile, Bezwan became a CARA (the Council for At-Risk Academics) fellow at UCL from June 2017 to June 2018.

Bezwan spoke with Long Dang of Index on Censorship about the events that transpired, his life in the UK, and his vision for Turkey’s future.

Index: What motivated you to become an academic?

Naif Bezwan: I could not really remember a certain point in my biographical trajectories in which I decided to become an academic, let alone pursuing an academic career. The idea of pursuing a career in academia has not been considered something worthwhile and esteemed by my generation of Kurdish and Turkish leftist intellectuals growing up under the brutal military rule in the 1980s. Quite the contrary, embarking on individualistic remedies was seen as a kind of opportunistic behaviour to save your skin, as it were, at the expense of a cause greater than yourself. So I think it has really been a process of gradual becoming rather than a decision at a certain point in time to be an academic. Having said that, it has nonetheless been a clear and conscious orientation towards, and commitment to, certain values, such as democracy, social change, justice, equality and self-determination that motivated us greatly. This motivation, I remember vividly, went hand in hand with an insatiable curiosity about the human condition, history, philosophy, as well as about the situation and destiny of your own society. All this was coupled with a pronounced sense of agency and responsibility for transforming what we perceive to contradict human dignity and freedom. Ultimately, it has been this intensive search for understanding of what has been in the past, as well as for what human dignity and flourishing requires, that led me to become an “academic”, or more precisely, an expelled one.

Index: Why did you become interested in working on Turkey’s Kurdish conflict ?

Naif Bezwan: First, as I indicated, it has been due to the life-world in which my political, cultural and intellectual socialisation, dispositions and positions were coming into being and shaped. I was born in a region of Kurdistan in Turkey, in Diyarbakir, where the Kurdish liberation movement has traditionally been very strong, where an awareness of being member of a distinct society is widespread, where interest in politics, culture and world affairs was distinctively strong. Second, I was raised in a family in which memories of brutal repressions of previous Kurdish generations by the Turkish state, including members of my family, namely my grandfathers and their relatives, were kept alive – their engagements were upheld and their sufferings were told, retold and remembered. A third factor that seems to have formed my orientation during my youth was a growing influence of socialist ideas adopted and defended by various Kurdish organisations and movements throughout 1970s and later on. So all these factors have provided a background to my epistemological interest in working on Turkey and Kurdistan. My time and higher education in Germany during my first emigration, and now in London, have bestowed me with the kind of resources needed to study this problem in-depth from a comparative and historical perspective, and with a degree of freedom necessary to inquiry this complex subject-matter.

To study the various aspects of the Kurdish society and conflicts as a Kurdish scholar almost per se makes you suspicious in the eyes of Turkish state authorities and can lead to your expulsion and imprisonment, as has been the case for many scholars over the years. But it can unfortunately also have consequences of a different kind even in Western countries, such as being branded as biased because of your Kurdish identity or being asked not to criticise the repressive policies leading up to your expulsion and emigration.

Index: On January 2016, 1128 academics signed a petition, entitled “We will not be a party to this crime”, demanding the Turkish government to end military oppression against the Kurdish population. What were your reasons for signing the petition? Were they professional or personal?

Naif Bezwan: It was a combination of both. There was a brutal ongoing war against the Kurdish population, a war whose effects we felt in our daily lives and the lives of our students. I was working at Mardin Artuklu University, which is located at the heart of the Kurdish region at the border between Turkey and Syria. I excruciatingly remember how young people and soldiers were killed everyday, lives and livelihoods destroyed as a result of the termination of the peace process by the government in the summer of 2015. I could not simply stand by and see all these atrocities while the whole community was being destroyed – my students and the people I knew were very affected by this policy of destruction. That is why I signed the petition, knowing that possible severe consequences would be arising from it.

Index: The petition called for a peaceful settlement between the government and the Kurdish population, and yet the government termed it “terrorism”. You were first suspended from your position because of a critical interview on the Turkish military incursion into Syria in August 2016. How do these incidents speak to the government’s system of oppression?

Naif Bezwan: I was suspended from my position for giving the interview with the Turkish Daily National. As an academic for International Relations and Political Science with a specific focus on Turkish domestic politics, political system, foreign policy and Kurdish issue, I argued that the Kurdish issue was essentially entrenched within Turkey, which meant that security would not be possible through more invasion or use of military violence internally and externally. The way to solve the problem, I stressed, was to return to the peace process which had been broken by the government. Only a couple of hours following the interview’s publication, I was called by the faculty administration to be handed down an official document. Upon my arrival, I was given a letter. This letter, in which a reference was made to the interview, was nothing but an order for my suspension that had been signed by the rector of the University. So I was immediately suspended from my position and then requested to give my defence as to why I gave the interview. In my defence, I emphasised that the interview was related to the core area of my expertise, and that suspension of academics and suppression of free speech cannot be the way in which academics arguments should be exchanged and universities function. My assessment, I added, might have been wrong or problematic. If so, however, it should have been responded through counterarguments instead of punitive measures. I have not yet been notified of the outcome of the administrative inquiry, but instead have been completely expelled from my position and public service through a decree-law in September 2016.

Index: Could you describe the hostile environment in Turkey after the failed coup attempt of July 2016?

Naif Bezwan: The coup attempt was a vicious attempt against democracy, but the government used it as the pretext to extend the dimension and size of oppression. In the aftermath of the failed coup, Erdogan said something very treacherously revealing – he depicted the coup as a kind of blessing. Why was it so? Well, this “blessing” was used first to intimidate the whole range of oppression, and second to consolidate his power. It was clear that it would be difficult to live in the country and therefore my partner and I decided to leave the country for the UK on 9th November 2016.

Index: How has life in the UK been for you?

Naif Bezwan: I think every form of forced exile contrary to freely chosen ways of immigration in search for a better life is painful. You are all of a sudden cut off from many things that make your life meaningful – your work, your relationships, your friends and family. After having migrated from Turkey to Germany in 1991, I freely decided to return to Turkey in January 2014, in the hope of doing something meaningful. I had just settled down and once again I was compelled to leave the country. The choice I had to make was between going into a new exile or being deprived of many things and activities that defined me and my way of life.

Being confronted with a forced immigration, one also needs to look on the bright side, try to create new possibilities and involve oneself in activities that would give meaning to one’s life again. In June 2017, almost a year after my arrival in London, I was granted the CARA fellowship at the Department of Political Science at UCL. Thanks to the fellowship, I was able to more systematically and continuously work and promote my studies and public engagement. I have completed two academic articles during the first months of my fellowship. I have been able to do a lot of research and participate in many academic conferences. In a group of other academics and friends, I became involved in establishing a London-based charity, the Centre for Democracy and Peace Research, which provides substantial support for our friends and colleagues back home. In all, being in the UK has been an uplifting opportunity, allowing me to continue with my studies and with my life.

Index: What is your perspective on the newly-expanded powers of Erdogan and their implications for the freedom of academics? What sort of support do you think is necessary for freedom movements to gain momentum? Could momentum be gained from within the country, or is some form of international intervention fundamental?

Naif Bezwan: As far as the character of the new regime is concerned, I think we have to keep in mind that the constitutional changes that introduced the new government system was made under a state of emergency. Opposition was silenced and intimidated, and there was no free press or free speech. This is very indicative of the character of the current regime. It is essentially an authoritarian, autocratic regime based on arbitrariness, with severe restrictions on free speech and a range of repressive policies at its disposal. For example, just three days before Erdogan was sworn in as president, there was an emergency decree through which about 18,000 civil servants, including academics, were dismissed. The message that the government wants to send is: we celebrate our victory through the intimidation and suppression of people, depriving them of basic rights, of the basis for life in dignity and freedom.

Given the nature of the current regime, two major outcomes seem to be possible. First, if there is a convergence between the parliament majority and president, which is currently the case, it would allow the president to exercise a constitutional dictatorship, in which the president can act in absolutely unbounded manners, since the dictatorial exercise of state authority is grounded in the very nature of the constitution itself. The current regime is authoritarian and autocratic in character, based on and emerged out of, extensive policies of intimidation, expulsion, fear and war-mongering. The other option would be a divergence between the parliament majority and president, which would result in an illiberal, dysfunctional regime. So: we had a choice between two equally undemocratic, unreasonable and repressive ways of governing the country. What makes things even worse is the fact that the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) – the far-right, anti-kurdish, anti-western, utterly racist party – now provides the president and his new regime with the necessary majority.

Given the fact that the country is increasingly becoming a big prison for the Kurds, minority groups, academics and critical voices, the work of the Kurdish and Turkish diaspora, as well as the support of the international community, is essential to strengthening democratic opposition and forces of transformation in the country. Due to the monopolization of the press in Turkey by the government, critics have no free space for acting and organizing themselves. This is why it is so important for organizations like Index to give voice to the people, their suffering and their resistance, in Turkey and beyond.

Index: Do you have hope that you will be able to return to Turkey, and pick up from where you left off?

Naif Bezwan: Going through all this process and being affected by it make you perhaps particularly sensible to the injustices directed at other people. I feel it incumbent upon me to do more academic work and be even more involved in civic duties to change the current situation and the utterly repressive regime. It is not an easy task at all. It requires patience and perseverance on the one hand, and creativity, solidarity and imagination on the other to generate new alternatives. I feel a responsibility to contribute the realising democratic and peaceful conditions in Kurdistan, Turkey and beyond.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content”][vc_column][three_column_post title=”Academic Freedom” full_width_heading=”true” category_id=”8843″][/vc_column][/vc_row]