8 Sep 2017 | Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

“Of course I am afraid. Only a fool wouldn’t be afraid at such a time,” said Ali Sirmen, a veteran journalist who has spent decades working at Cumhuriyet, whose writers and executives — five of whom remain imprisoned — are on trial facing terror charges.

This is not the first time journalists from Cumhuriyet have faced trial. The newspaper’s long history — it was founded in 1924 and christened by none other than the republic’s founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk; “cumhuriyet” is the Turkish word for republic — is one of “prisons and clampdowns” according to Cumhuriyet’s own wording. The newspaper has been shut down many times, many of its employees imprisoned and six of them were murdered over the course of its 93-year long history.

The 78-year-old Sirmen first started at Cumhuriyet in 1974 and wrote for the newspaper until 1991, when he walked with 80 other journalists in protest of the editorial line adopted by then editor-in-chief Hasan Cemal. After a seven year stint at the then-mainstream Milliyet, Sirmen returned to Cumhuriyet in 1998.

Sirmen was imprisoned both after the 12 March 1971 and 12 September 1980 military coups for his writing. He has seen both civilian and military prisons. He was eventually acquitted both times, but only after serving time in prison.

“If I had stayed 20 more days in prison in the 12 September period, I would have completed the sentence they were seeking for me,” he remembers. “The practice of pretrial detention as punishment for journalists started in those times,” Sirmen said.

Keeping up appearances

According to Sirmen, trial proceedings of military eras were mostly a show, but they were still less farcical than the courtrooms of post-15 July Turkey. “They [the courts of military rule periods] at least tried to keep up appearances. They abided by established procedures; here, there is no such concern at all.”

“As someone who knows the prisons of the coup periods, I have said many times that the situation is much worse today. For example, when I was acquitted in the Madanoğlu trial [in which Sirmen was accused of supporting a failed coup in 1971] the Military Court of Cassation overruled our convictions twice in spite of pressure from the military regime. Can such a thing happen today?” he asked.

Hasan Cemal, the editor-in-chief whom Sirmen walked out on in 1991, agrees. “Cumhuriyet was shut down during both coup periods; saw immense levels of crackdowns, its writers were imprisoned many times, but not to the extent that we see today.”

Like Sirmen, Cemal agrees that the judiciary tried to act in compliance with the law despite pressure. “There was no rule of law in the 12 September period; true, but to a certain extent, there was a state that heeded laws. We don’t have that anymore.”

A secular, forward-looking newspaper

But Cemal doesn’t believe in comparisons. “It might be misleading comparing one grievance with another. If journalism is considered a crime in our day, if freedom of expression is being trampled under feet, if the media today has only one voice, what good would it do to compare this horrible situation with the 12 March or 12 September period?”

Although the two journalists might have locked horns in the past, both name “belief in democracy, secularism and the rule of law” as the definitive values which Cumhuriyet stands for. Both of them also agree that it is precisely why the newspaper, which is doing poorly both financially and in terms of circulation, has come under attack. Why would anyone bother to silence an apparently moribund newspaper?

“The way Cumhuriyet views secularism, democracy, the supremacy of law, freedoms and human rights; its face is turned towards the west; all of these are unacceptable for the Erdoğan mentality. Because if Cumhuriyet is the west, then Erdoğan is the east,” according to Cemal. [/vc_column_text][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Media freedom is under threat worldwide. Journalists are threatened, jailed and even killed simply for doing their job.” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fcampaigns%2Fpress-regulation%2F|||”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship monitors media freedom in Turkey and 41 other European area nations.

As of 8/9/2017, there were 522 verified violations of press freedom associated with Turkey in the Mapping Media Freedom database.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship campaigns against laws that stifle journalists’ work. We also publish an award-winning magazine featuring work by and about censored journalists. Support our work today.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”vista_blue”][vc_column_text]A game of thrones

The incident in which dozens of writers left Cumhuriyet en masse in protest of Cemal in 1991 was not the first episode of ideological shifts in the newspaper’s history manifested as a show-down. In fact, the newspaper is notorious for infighting, which, this time, gave the prosecutors material to base the current trial on. In fact, two reporters whose testimonies were included in the indictment still work at the newspaper and they will testify in Monday’s trial.

On 2 April 2013, the Cumhuriyet Foundation — which appoints the editor-in-chief of the newspaper — saw a change of guard: a more liberal group, as opposed to the traditionally hard-line Kemalist executives, was elected to the seats on the foundation’s executive board. Testimony from some of the former board members are also included in the indictment, and these individuals will also testify — most likely against the defendants — in the hearings that begin on 11 September.

The new foundation team, the prosecutor says, hired columnists and allowed reporting that served the purposes of the Fethullah Gülen Network, which is referred to as a terrorist organisation by Turkish courts.

A legal battle over the foundation’s leadership is still ongoing and pro-government media has openly sided with the old guard at Cumhuriyet. That is a separate case, but Cumhuriyet being forcefully returned to its previous executives is not a far-fetched possibility.

A brief history of government pressure on Cumhuriyet

Detentions and arrests

Detention and imprisonment of Cumhuriyet journalists go back a long way. In one of the notable cases in 1962, contributor Şadi Alkılıç and editor Kayhan Sağlamer were arrested and imprisoned over an article published in Cumhuriyet praising socialism. Alkılıç was acquitted in 1967 after a higher court overruled his sentence handed down over socialism propaganda.

İlhan Selçuk, one of the newspaper’s iconic names, who was also the founder of the Cumhuriyet Foundation, and the then editor-in-chief of the newspaper, Oktay Kurtböke, and several other Cumhuriyet writers were detained after the 12 March 1971 coup d’état — along with several others. Selçuk was subject to torture in prison in this period, where he and his fellow defendants were accused of supporting a failed coup attempt that would have taken place three days prior to the actual coup.

Ali Sirmen, Erdal Atabek and Ataol Behramoğlu were imprisoned by the courts of the 1982 military regime for membership of the left-wing Peace Association.

More recently, in 2008, the newspaper’s Ankara Bureau Chief Mustafa Balbay was imprisoned in an investigation into Ergenekon, a behind-the-scenes network which allegedly plotted to overthrow the AKP government, according to the prosecutor. Columnist Erol Manisalı was also arrested in the same investigation in 2009; he was released after three months in prison. İlhan Selçuk was also detained in the same investigation.

In May 2016, the newspaper’s former editor-in-chief Can Dündar and Ankara Bureau Chief Erdem Gül were arrested over a news story which suggested that the Turkish government sent weapons and ammunition to armed jihadist groups in Syria.

Outside the current case, Oğuz Güven, editor of the newspaper’s internet edition, was imprisoned for a month when for a headline cumhuriyet.com.tr used describing the accidental death of a prosecutor who led investigations into the 15 July 2016 failed coup.

Closures:

The newspaper was shut down for the first time on October 29 1934 for 10 days. Then it was shuttered for 90 days in 1940 over its publications that went against the official line of the government. After the 12 March 1971 coup d’état, it was shuttered for 10 days. It was shut down twice following the September 12 1980 coup d’état in Turkey by the military junta, first over an article by İlhan Selçuk, which praised “Kemalizm” and later over a book written by the newspaper’s chief columnist and owner Nadir Nadi.

Assassinations:

Cumhuriyet journalists have also faced fatal attacks. Six Cumhruiyet journalists, all of whom were known for their staunch secularist views, have been killed since 1978. Columnist Server Tanilli, an Istanbul University academic, was left paralysed following an armed attack on 7 April 1978. Cumhuriyet columnist Cavit Orhan Tütengil was assassinated on 7 December 1979 while waiting for a public bus.

The newspaper also took its share of the violence at the height of Turkey’s unsolved murders — which are commonly believed to be state sponsored– in the 1990s. Columnist Muammer Aksoy, who was also the president of the Atatürkist Thought Assassination, was shot dead while he was on his way home in Ankara in 1990. Socialist columnist Bahriye Üçok was killed by a bomb package sent to her house on 6 October 1990. Investigative journalist Uğur Mumcu was killed when a bomb placed in his car detonated on Jan. 24, 1993. Columnist Onat Kutlar died as a result of injuries sustained also in a bomb attack on 30 December 1994. Cumhuriyet’s Ahmet Taner Kışlalı was also killed in front of his house in a bomb attack in 1999.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1504883275252-0c531056-a363-8″ taxonomies=”7790″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Aug 2017 | Mapping Media Freedom, media freedom featured, News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

16 July: Violence following attempted military coup. Credit: deepspace / Shutterstock.com

In the year since the failed coup attempt on 15 July 2016, Turkey has cemented its position as the largest jailer of journalists in the world, with around 166 journalists in prison by the end of June 2017.

Many have been accused of being affiliated with terror organisations including the Kurdish PKK, the left-wing DHKP-C and the Gullenist Movement, the group accused of being behind last year’s coup attempt.

This is the case with the 18 writers, cartoonists and executives from the Cumhuriyet opposition newspaper, who went on trial on 24 July, accused of supporting in their coverage these very groups.

Seven of the defendants, including cartoonist Musa Kart, were released under judicial supervision. They must report to the authorities regularly in the lead-up to the next hearing on 11 September.

“The Turkish state’s reaction to the attempted coup on their democratic institutions led to an unparalleled level of attacks on press freedom,” said Hannah Machlin, project manager of Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom platform. “One year later, the media sphere has been carved out, with hundreds of journalist in jail, being forced to flee or have lost their jobs following the closure of outlets. This trial is clearly political and the state’s attempt to criminalise journalism.”

MMF has been closely monitoring the situation over the last year. Here are some of the more recent cases of journalists being accused of being connected with terrorism.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_separator color=”black”][vc_custom_heading text=”Media freedom is under threat worldwide. Journalists are threatened, jailed and even killed simply for doing their job.” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fcampaigns%2Fpress-regulation%2F|||”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship monitors press freedom in Turkey and 41 other European area nations.

As of 30/8/2017, there were 521 verified incidents associated with Turkey in the Mapping Media Freedom database.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship campaigns against laws that stifle journalists’ work. We also publish an award-winning magazine featuring work by and about censored journalists. Support our work today.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator color=”black”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

On 12 July the Ankara Chief Prosecutor’s office issued detention warrants for 34 former employees of the state-owned Turkish Radio and Television network without providing their names. On 19 July eight former employees were imprisoned under charges of “belonging to a terrorist organisation”.

Media reports said that in Istanbul, warrants to detain 18 people who formerly worked for TRT were issued and that ten of these people were captured. One was released after being interrogated by the police.

The other nine, who were referred to court after their police interrogation, were: reporter Efnan Y, chief technician Faysal A, engineers Serkan C and Özgür Ş, chief technician Satı D, production assistants Şule R, Uğur Y, Tuba E and Yunus G.

Eight of these individuals were put under arrest while one was released under judicial control measures.

On 27 July, Erdoğan Alayumat, a reporter for the pro- Kurdish dihaber news agency, was arrested on terror charges.

Alayumat was detained on 13 July in Gaziantep together with fellow dihaber reporter Nuri Akman, while working on a news report. Later, they were transferred to Hatay province. The two were referred to a court on charges of “membership in a terrorist organisation.”

The court released Akman on judicial probation terms but ruled to arrest Alayumat.

Also on 27 July, the Evrensel columnist Yusuf Karataş was arrested as part of a Diyarbakır-focused operation into the Democratic Society Congress, a union of pro-Kurdish civil society organisations.

Karataş was arrested after visiting the Diyarbakır Police Station for a police interrogation regarding the investigation. He was then referred to a prosecutor, who asked the judges to arrest the journalist.

Karataş was asked questions relating to why he joined a protest of the Roboski massacre – where 34 Kurdish citizens were killed in a bombing by Turkish air force jets in 2011.

On 28 July, two employees of the pro-Kurdish daily Özgürlükçü Demokrasi, Serkan Erdoğan and Özkan Erdoğan, were arrested on charges of “membership in a terrorist organisation” and “conducting propaganda for a terrorist organisation”.

Özkan Erdoğan was initially detained for being in possession of a magazine deemed “illegal” by the Turkish authorities.

Serkan Erdoğan, a reporter for the dailu was detained in a home raid on the same night also in Mersin and later arrested by a Peace Judgeship on the same charges. Reports have said the two Özgürlükçü Demokrasi employees share an apartment, but they are no relation to each other in spite of the shared last name.

On 1 August French journalist Loup Bureau was arrested in Sirnak on charges of being a member of a terror organisation.

Bureau was first detained on 26 July at the Habur crossing, where he was crossing into Turkey from Iraq.

After five days in police custody, he was charged and taken to a prison in the town of Şırnak. A gag order was imposed on his case.

On 18 August Mehmet Sıddık Damar, formerly a reporter for the shuttered news agency DİHA, was arrested in Mardin’s Kızıltepe district over his social media posts.

Prior to his arrest, Damar visited the Kızıltepe Courthouse to testify in an investigation against him.

The court ruled for his arrest on charges of “propaganda on behalf of a terrorist organisation” based on several tweets and social media posts.

Damar was sent to Mardin Prison.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1504104629275-dd1fbb43-7214-3″ taxonomies=”7355″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

23 Aug 2017 | News and features, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

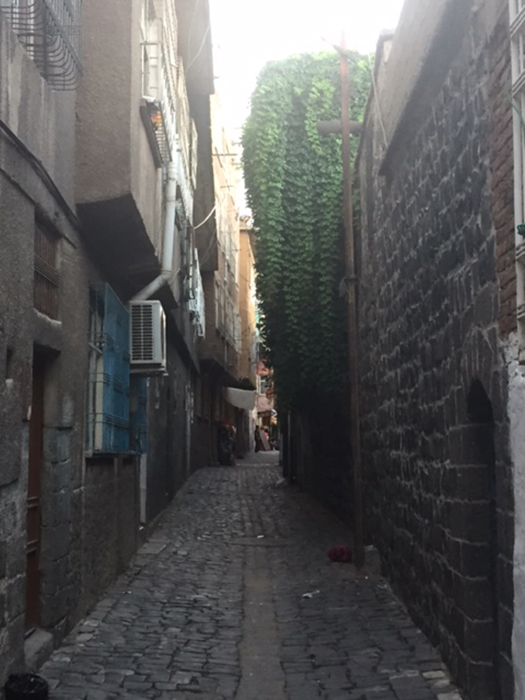

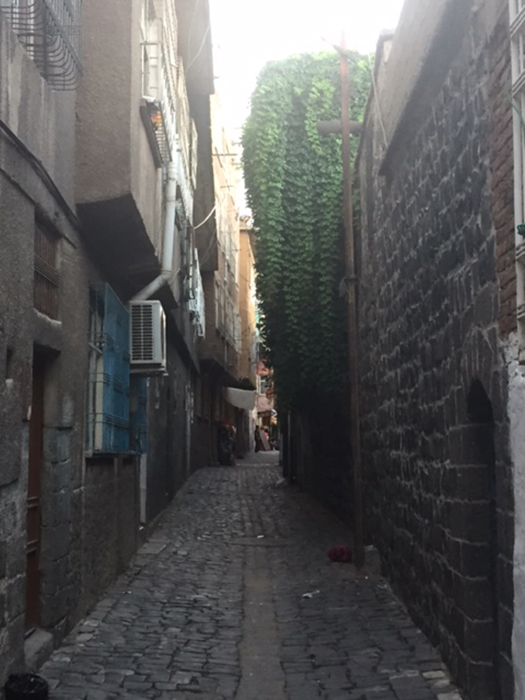

The district of Sur was the first settlement in Diyarbakır, which, according to some sources, has been inhabited for five thousand years and hosted 33 civilisations. The area’s architecture — a rich combination of churches and mosques, mansions and modest homes from different eras — is evidence of its long history and well-established community.

Since June 2016, parts of Sur have demolished as part of an “urban regeneration programme”. In the first stage, homes in the Sur neighbourhoods of Lalebey and Alipaşa were demolished. In the process, the primarily Kurdish communities were destroyed: some families moved away, their connections to their personal history severed; others stayed put, clinging to their homes and their lives in the neighbourhoods with a tenacious resistance to being erased.

The 2016 demolitions were the latest phase in a long process that began in 2009. That’s when the Mayoralties of Diyarbakır and Sur signed an agreement with Turkey’s Environment and Urban Planning Ministry and the Mass Housing Administration to replace the local housing stock with new homes in a style appropriate to the area. Beginning in 2011 with the bulldozing of homes of houses in the Alipaşa neighbourhood, the residents have been at odds with a government they see as inattentive and arbitrary.

During the 1990s, there were violent clashes between Turkey’s military and armed groups aligned with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). Thousands of villages were evacuated by state forces. Displaced people became impoverished when they settled in the city of Sur.

When the displaced began arriving in Sur, new housing was built that quickly overwhelmed the area’s mosque and architecture.

Historic buildings were destroyed in order to build housing for the displaced and the area quickly became a slum. In a short time, some of the new housing became unhealthy and unstable.

With neighbourhoods of historic buildings, narrow streets and local culture, the city of Sur would have lost these features through its urban regeneration project. Moreover, the money set aside to buy properties was not enough to allow people to start new lives elsewhere. As a result, the local government suspended the project.

Though the demolitions had been halted because the inhabitants of the area did not want to evacuate their homes and civil society organisations had objected to the destruction of the area’s history and community, an emergency decree issued after the failed July 2016 coup restarted the urban regeneration project.

In May 2017, authorities told residents of Sur’s Lalebey and Alipaşa neighborhoods to evacuate their homes. Families that resisted were told they would be forcibly removed. In the face of the threat, some families left the area. Those that remained had their water and electricity turned off.

Residents of Lalebey and Alipaşa have used the walls of the neighbourhoods to make it clear they do not want to leave their homes.

Residents of Lalebey and Alipaşa have used the walls of the neighbourhoods to make it clear they do not want to leave their homes.

Cumali, sitting in front of his evacuated house, did not want to leave Sur. He has been moved to temporary housing on a road that has not yet been demolished. Cumali says: “I was born in Sur, I grew up, got married. Let us relax. I want to die in Sur.”

Mevlüde Ak was born and grew up in a house in Sur. She gave her house in Sur to her married, unemployed son. She lives with her husband in their small shop. After closing time, they put down beds on the floor and sleep there. Mevlüde Ak says: “They offered me 60,000 Lira for our house. This money would not be enough for us to buy a new home. We’re not leaving. If they wish, let them bring it down on top of us.”

Aynur Güneş’s husband died years ago. She has no children. She lives by selling things like chocolate, gum, crisps in front of her house because it is close to a school. She explains why she does not want to leave Sur as follows: “I know nothing will happen to me here. If something happens: if I fall ill, for example, my neighbours will immediately come to help me. That’s how we grew up in Sur. If I have to live in an apartment I will die.”

Civil society organisations, supported by artists, journalists and politicians, have banded together with Sur residents to fight the ongoing destruction in the neighbourhoods. The campaign is helping to organise petitions and community gatherings, like this one breaking the fast during Ramadan.

9 Aug 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Statements, Turkey, Turkey Statements

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Hamza Yalçın (Photo: Odak magazine)

The arrest of Turkish-Swedish journalist Hamza Yalçın by Spanish authorities is a gross abuse of the Interpol international arrest warrant system and a brazen attempt to stifle press freedom by Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Index on Censorship calls on Spanish authorities to allow Yalçın to return to Sweden.

Yalçın was detained at Barcelona’s El Prat airport on 3 August following an international arrest warrant through Interpol initiated by Turkey.

A day later he was arrested by Spanish police on charges of “insulting the Turkish president” and “terror propaganda” related to an article he wrote for Odak magazine. Yalçın was the chief columnist for Odak and the coordinator for its Training and Solidarity Movement. On 18 March, Turkish prosecutors launched an investigation into Doğan Baran, Odak’s managing editor, and Yalçın for his article entitled The Latest Developments in the Military and the Revolutionary Struggle. Both Baran and Yalçın face charges for “insulting the president” and “denigrating the military.”

“This is a clear abuse of the Interpol system because it is a direct violation of Article 2 of its constitution, which requires respect for fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals. It is extremely concerning that an exiled journalist can be arrested for exercising their right to freedom of expression,” said Hannah Machlin, project manager for Mapping Media Freedom, Index on Censorship’s project monitoring press freedom in Turkey and 41 other European area countries.

The Spanish authorities now have 40 days to decide whether to extradite Yalçın back to Turkey.

“Index demands Spain free Hamza Yalçın and allow him to return to his home in Sweden,” Machlin added.

Yalçın was arrested in 1979 on charges of being linked to the People’s Liberation Party-Front of Turkey (THKP-C) Third Way organization. Odak reported that Yalçın was given two consecutive life sentences by the military junta, which was then in control of the Turkish government, for his “revolutionary activities.” He was granted asylum by Sweden and has lived there since 1984.

Odak magazine, which is campaigning for his release, said in a statement that Yalçın “has been made into a target many times for his articles and values.”

The Council of Europe’s parliamentary assembly published Resolution 2161 in April 2017 on the abuse of the Interpol system. The resolution underlined that “in a number of cases in recent years, however, Interpol and its Red Notice system have been abused by some member States in the pursuit of political objectives, in order to repress freedom of expression.” [/vc_column_text][vc_separator][vc_custom_heading text=”Media freedom is under threat worldwide. Journalists are threatened, jailed and even killed simply for doing their job.” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” use_theme_fonts=”yes” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fcampaigns%2Fpress-regulation%2F|||”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship monitors press freedom in Turkey and 41 other European area nations.

As of 9/8/2017, there were 503 verified incidents associated with Turkey in the Mapping Media Freedom database.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]Index on Censorship campaigns against laws that stifle journalists’ work. We also publish an award-winning magazine featuring work by and about censored journalists. Support our work today.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1502284900540-fbb3abe9-4651-4″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]