16 Jun 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Press Releases

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

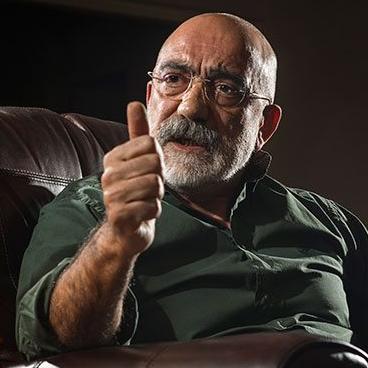

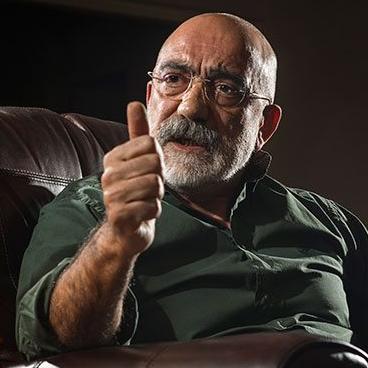

Journalist Ahmet Altan is charged with inserting subliminal messages in support of the failed 15 July coup in Turkey.

On 19 June, the first hearing will take place in a trial concerning 17 defendants, including a number of journalists. Among the defendants are prominent novelists and political commentators, Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan and Nazlı Ilıcak. The case is the first trial of journalists accused of taking part in last year’s failed coup

The case is the first trial of journalists accused of taking part in last year’s failed coup attempt and may shed light on how the courts will approach numerous cases concerning the right to freedom of expression and the right to a fair trial under the state of emergency.

Representatives of Article 19, Amnesty International, Index on Censorship, Norwegian PEN and PEN International will be attending the hearing in order to demonstrate solidarity with the defendants, and with media freedom more broadly in Turkey. The Bar Human Rights Committee of England and Wales and the International Senior Lawyers Project are also sending observers to the hearing.

The charges against the accused are detailed in a 247-page long indictment which identifies President Erdogan and the Turkish government as the victims. Defendants Ahmet Altan, Mehmet Altan and Nazlı Ilıcak are charged with “attempting to overthrow the Turkish Grand National Assembly”, “attempting to overthrow the Government of Turkey”, “attempting to abolish the Constitutional order” and “Committing crimes on behalf of an armed terrorist organisation without being a member”. The remaining defendants are additionally charged with “membership of a terrorist organisation”, in reference to the Gülen movement who the Turkish government accuses of having orchestrated the coup attempt.

The majority of those on trial are either currently in exile or have been held in pre-trial detention for almost 10 months. On 14 June, the European Court of Human Rights wrote to the Turkish government requesting its response to a number of questions to determine whether the human rights of seven detained journalists, including the Altans and Nazlı Ilıcak, have been violated due to the long pre-trial detention.

We believe the trial to be politically motivated and call on the authorities to drop all charges against the accused unless they can provide concrete evidence of commission of internationally recognisable criminal offences and to immediately and unconditionally release those held in pre-trial detention.

Article 19 has prepared an expert opinion examining the charges against the Altan brothers, at the request of their defence lawyers, which will be submitted to the court on Monday morning. The opinion argues that the charges levelled against the Altans amount to unlawful restrictions on the exercise of the right to freedom of expression.

For more detailed information regarding the context for free expression in Turkey, please see a joint statement submitted to the UN Human Rights Council in May 2017.

For further information please contact:

Sarah Clarke, International Policy and Advocacy Manager, PEN International, sarah.clarke@pen-international.org

Georgia Nash,Programme Officer – Middle East & North Africa / Europe & Central Asia, ARTICLE 19, [email protected]

Melody Patry, Head of Advocacy, Index on Censorship, [email protected]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1497944733154-20b659a7-0b15-10″ taxonomies=”7355″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row full_width=”stretch_row_content_no_spaces” content_placement=”middle”][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91122″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/05/stand-up-for-satire/”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Jun 2017 | Campaigns, Campaigns -- Featured, Turkey, Turkey Statements

Nuriye Gulmen, a professor of literature, and Semih Ozakca, a primary school teacher, were both fired following the issuing of emergency decree 675 by Erdogan’s government.

In the wake of the July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan dismissed over 8,000 academics from state institutions following Emergency Decree 675. Literature professor Nuriye Gulmen and primary school teacher Semih Ozakca were two such individuals affected by the purge. Both Gulmen and Ozakca were dismissed and have been detained by Turkish authorities over 30 times, most recently on 22 May, for their demands to be reinstated to their positions. They are now facing terror charges simply for asking for their job back.

We urgently need your help to call for the release of Nuriye Gulmen and Semih Ozakca and express your solidarity with their cause.

Gulmen and Ozakca began a hunger strike, which is currently on its 90th day, to protest the crackdown on academic freedom. Consuming little more than salt water, a single B vitamin, and a sugar solution, Ozakca has lost over 37 pounds and Gulmen has experienced heartburn, difficulty moving, and trouble concentrating. Both academics suffer from muscle atrophy and are now wheelchair bound.

Read more about Gulmen and Ozakca’s protest and the current crackdown on freedom of expression in Turkey

Index on Censorship stands in solidarity with Gulmen and Ozakca and pledges its full support for their right to protest. We ask you to do the same: demanding an end to the dismissal of academics and the immediate release of Nuriye Gulmen and Semih Ozakca. While their plight has gained international attention, both strikers have received little recognition from their own government. As such, we ask you to speak out on Ozakca and Gulmen’s behalf in the form of a brief video expressing solidarity with their strike and requesting academic freedom for Turkey.

Take Action

— Post a solidarity message on social media.

— Share the story of Nuriye Gulmen and Semih Ozakca with your network.

— Tweet: [socialpug_tweet tweet=”I stand with @nuriyegulmen, @semihozakca and #academicfreedom #DontletNuriyeAndSemihDie #Turkey” remove_url=”yes” remove_username=”yes”]

6 Jun 2017 | Academic Freedom, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”91204″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes” alignment=”center”][vc_column_text]Turkey’s authoritarian shift has been unmistakable this past year. Following the coup attempt in July 2016, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s purge of state institutions has led to mass dismissals, including over 8,000 academics. Similarly, over 2,000 schools, dormitories and universities have now been shut down, causing great concern for Turkish education.

Nuriye Gulmen, a professor of literature, and Semih Ozakca, a primary school teacher, were both fired following the issuing of emergency decree 675 by Erdogan’s government. Shortly afterwards the pair joined forces demanding that academics across Turkey get their jobs back. Since they began protesting over six months ago with the slogan “I want my job back”, Gulmen and Ozakca have been detained by Turkish authorities over 30 times, most recently on 22 May. It is being reported that they will be tried for “membership of a terror organisation”.

The pair embarked on a hunger strike on 9 March 2017, which is now in its 90th day. While their story has now gained much international attention, they have little recognition from their own government.

“Amid a nationwide crackdown on freedom of expression, a hunger strike is the form Nuriye and Semih have chosen to protest the dire situation faced by academics in Turkey,” Index on Censorship’s head of advocacy Melody Patry said. “Index calls for their immediate release and for all charges against them to be dropped.”

Due to the massive number of arrests of journalists, academics and others within the last year, there is a serious backlog in the Turkish courts which means it could be a year from now before their case is even heard.

After protesting in various forms, from collecting signatures, distributing flyers and going door to door to share their story, Gulmen and Ozakca found little success. Instead, they were continuously detained by authorities before being released soon after.

Throughout their current hunger strike, there has been a significant deterioration in their health, and Ozakca has lost over 37 pounds from a diet consisting of salt water and sugar solutions with a single B vitamin. Gulmen says she experienced heartburn and a drastic drop in blood pressure which then lead to aching muscles, difficulty moving, loss of tissue, sensitivity to light and trouble concentrating. Eventually, the pair experienced severe difficulty walking as well as muscle atrophy, and are now both confined to wheelchairs.

This has not, however, hindered their hope of victory in their battle with the government. In a video released earlier in May, Gulmen stated that the solidarity and support of the public was making her feel better and that the pair’s “resistance is continuing and we will not stop until we gain our rights again.”

Similarly, they stated their latest detention will not halt their hunger strike, as they promised to continue it in prison.

The solidarity and support, which they have expressed thanks for, has come in many forms. David Harvey, professor of anthropology and geography at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, released a video providing support in which he said: “I want to express my solidarity with my friends and colleagues who are on a hunger strike in Turkey. I think that the sooner we enter a democratic process in Turkey, the better. I support all the actions made for this purpose with all my heart.” Turkish singer, Sezen Aksu, has also offered support and called on the Turkish government to take action and “listen to their voices”

Over 145,000 public workers have been fired since the failed coup, resulting in an array of protests and public demonstrations by activists and the general public throughout the world. Many Turkish public workers have protested on their own behalf in an attempt to regain their jobs and draw attention to the government crackdown.

Many, including Efe Sevin, a Turkish post-doctoral researcher at the University of Fribourg, believe the coup has become an excuse for Erdogan to do anything he wants, including stamping out opponents and potential opponents by labelling them as enemies of the state and members of terrorist organisations.

“Erdogan is very dismissive of intellectual capital and opposition,” Sevin added. “The only reason one may oppose him is if they have some secret/hidden agenda to overthrow the government or they are terrorists or they are supported by foreign powers to do so.”

Thinking about the overall impacts of these dismissals on Turkish academia depresses Sevin both personally and professionally depressed. “Especially with the most recent decrees that dismissed peace petition signatories that had no known ties with Gulen, I think ‘will there be a new decree with my name on it?’ is a fear all Turkish faculty members share.”

“Even though it is becoming more and more difficult to defend academic freedom under the current regime, we should not pretend that Erdogan took over an academic freedom utopia,” Sevin said. “Especially after the coup in 1980 and the establishment of Council on Higher Education, academic freedom was at best questionable in Turkey.”

Similarly to Gulmen and Ozakca, one of Turkey’s most prominent academic reformers, Kemal Guruz, was sentenced to thirteen years and eleven months in prison by a criminal court in Turkey on 5 August 2013. His ordeal began in 2009 when he was accused of being a member of a secret terrorist organisation and ”reached a climax” in 2012 when a further charge of attempting to forcibly overthrow the government was levelled at him.

Guruz, who served 438 days of his sentence before being released, told Index: “The two cases, though seeming to have fizzled out, are still continuing in courts. I use the qualifier ‘seeming to’ because you never know how things will turn out in the Turkish courts of today.”

“All of the prosecutors who prepared the indictments against me and all but one of the judges who presided over my trials in the past are either in jail or fired or have fled the country,” he added. “I understand what is going on today is a struggle between the legitimate government and the Gulenists who appear to have attempted a coup last summer, but I must add that the two sides were in cahoots in the past, especially in my two court cases.”

“Apparently, both sides hate my me for my staunchly secular and pro-Western stand.”

As Gulmen and Ozakca’s hunger strike continues, efforts to get the Turkish government to acknowledge them are growing more urgent. Index urges prominent public figures to follow the actions of David Harvey and speak out on Nuriye’s and Semih’s behalf in the form of a short video expressing solidarity. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/c9pyXZ8pTGc”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1496766579296-290161d0-415f-4″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

6 Jun 2017 | News and features, Turkey

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship contributor Ece Temelkuran’s latest novel is Women Who Blow on Knots.

Turkish author Ece Temelkuran is growing increasingly anxious about life under President Erdogan, she told Index on Censorship.

“After the failed coup attempt, the crackdown began on journalists, but we thought that writing fiction would provide a safe shelter,” she said. “Now we are seeing even the novelists are being targeted, and it makes you think there is no haven for anyone with critical thought.”

Asked whether her worries have begun to affect her own work, she paused before adding: “There is no justice in Turkey as we know it in the West. We don’t know what tweet, what thing you write could be the thing that puts you under the spotlight. The unhappiness in Turkey is so big, so palpable that you can touch it. It paralyses the human mind. Turkey does not let you do any intellectual work.”

However, Temelkuran, speaking to Index in London at an event to promote her new book The Women Who Blow on Knots, insisted that she would never allow Erdogan to force her to flee her homeland.

“The idea of leaving Turkey permanently is horrible because it deprives you of home, which I believe is inhumane. The supporters of Erdogan are constantly claiming that they are the ‘real people’ of Turkey, and I feel we have to constantly remind them that we are also real people.”

With the country heading down an authoritarian path following Erdogan’s success in a recent referendum that granted him vast new powers, Temelkuran believes Turkey faces a long road back. “It’s not easy to be hopeful, but one can be easily inspired by the people who are resisting,” she said, giving the example of two educators, Nuriye Gulmen and Semih Ozakca, who went on hunger strike in March 2017 in protest at losing their public sector jobs in the post-coup purge. Soon after Temelkuran’s interview, the pair were arrested and charged with membership of a terrorist organisation. They vowed to continue striking in prison.

The Women Who Blow on Knots tells the story of a group of women travelling through the Middle East during 2011’s Arab Spring. In conversation with author Diana Darke, Temelkuran explained that the title of her book is a reference to a passage from the Koran warning of the evil of women who performed witchcraft by blowing onto knotted rope, inverting the idea into an acknowledgement of female power.

“If our breath is so strong why not use it,” she said. “The main idea is that women blow life into things, into men, into children, into anything. They create life.”

The novelist also referred to one scene in which a group of Libyan militia women are watching Sex and the City, saying that she believes cultural divisions are overrated. “We’re watching the same TV series, using the same brands, reading the same books, we are watching the same Trump, whatever. The world is not completely like one village, but the cultural references are getting more and more common.”

However, in the context of a divided Turkey, she said that “it is as if there is this soundproof wall” in the middle of the country, with neither east nor west caring to learn about life on the other side. “This is something that I learned in early ages – the ones who stand in the middle get shot by both sides.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1496743531699-19a91ff0-06b4-6″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]