6 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Bülent Korucu, former columnist for Zaman and former editor-in-chief of Aksiyon.

As I’ve been writing for months now, the job that runs the highest risk in Turkey is, without a shred of doubt, journalism.

So you can imagine my sense of bitterness when I woke yesterday to the unanswered cries of despair from a teenage boy trying to save his mother from unlawful imprisonment.

“I am the son of journalist Bülent Korucu,” Tarık Korucu tweeted on 2 August. “Since my father is not found, my mother has been taken hostage for six days now. Please, I beg you, do not stay silent on this unlawful act.”

Hacer Korucu, who is the mother of five children, was taken into police custody on 31 July when the Korucu family flat was raided. The search was part of the crackdown on 42 journalists, many of whom were affiliated with Zaman daily. Bülent was on the list. His current whereabouts are unknown.

Earlier, Tarık tweeted that the police refused to allow his mother to take her one-year-old baby with her. They told his elder brother: “We will narrow the circle around you until your father comes out, and you will be next.”

Tarık’s despair, which was heartwrenching, reached a new low yesterday. He sent out “help us, speak out for us!” messages to a number of parliamentary deputies and journalists like Can Dündar. Only one deputy, Mahmut Tanal from the main opposition, CHP, reacted. Large chunks of the Turkish media are too busy these days attacking their colleagues and outlets in the West. Many Turkish columnists are joining the government chorus which demonises those in the media who are supposed to be Gülen affiliated, while ignoring the Korucu family’s plight in a mood of revenge.

Only brave, independent news sites like Diken, T24 and the Platform for Independent Journalism that reported the case. The rest maintain a deadly, acrimonious silence.

Yesterday, Korucu’s children were told they could go and visit their mother if they could find a lawyer in the ultra-conservative eastern city of Erzurum. This was impossible. “We can not find a lawyer for my mom,” Tarık tweeted. “Unfortunately, lawyers are done for as the rule of law collapsed over here. There isn’t a lawyer with a conscience in this big city.”

I am left speechless. And we still don’t know the grounds on which Hacer is kept in custody.

As of Friday, 42 journalists have been detained since the coup attempt. This brings the total number of jailed journalists in Turkey up 77, possibly the highest number of any country in the world.

In addition, we learned yesterday of two Kurdish reporters arrested in Yüksekova, in Hakkari province.

Korucu family’s tragedy is only a small part of an immense drama, leaving me in no doubt that journalism is the riskiest profession in Turkey.

According to European Journalism Observatory: “More than 100 Turkish media outlets have been closed, their assets seized by the government. Critical newspapers including Yarina Bakış, Özgür Düşünce, Meydan and Taraf, as well as the news site Haberdar and pro-Kurdish news agency DİHA have ceased publishing.”

A key aspect in this updated data has escaped the attention of my Western colleagues. An endless stream of seizures and the demonisation of the media mean that hundreds of journalists who do not end up in jail find themselves out in the streets, marked as “toxic” simply because they are abiding by the principle of remaining critical of power structures. Many will never again find a job in parts of the “central” media, which has been invaded by the culture of self-censorship.

Many of us journalists have lost outlets we’ve worked and are left without income. Many are doomed to either starvation or obedience to the powers that be. We have no chance of being employed in decent conditions unless a miracle happens or we receive mercy from our freedom-hating rulers. This is the real tragedy that has swooped over journalism in Turkey.

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

More Turkey Uncensored

Six more journalists jailed in Turkey

Silence is the enemy of democracy

Tough times ahead for Turkey

Dunja Mijatović : Turkey must treat media freedom for what it really is – a test of democracy

Turkey rounding up reporters, editors and columnists

Turkey’s rising censorship: How did we get here?

Erdogan is ruling Turkey by decree

The largest clampdown in modern Turkey’s history

Escalation in the clampdown on Turkey’s media and academia

Mapping Media Freedom: A disastrous week for Turkish journalism

As the purge deepens in Turkey, is a self-coup underway?

Critical Turkish media is cracking under pressure

A noble profession has turned into a curse

“Judicial coup” sends clear warning to Turkey’s remaining independent journalists

Can Dündar: Turkey is “the biggest prison for journalists in the world”

Turkey’s film festivals face a narrowing space for expression

4 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan interviewed on Italy’s RAI News 24

Turkey’s third post-coup week has been full of uncertainties, suspicion and concern. As of Wednesday morning there were 1,297 individuals subject to an international travel ban, among them 35 journalists and 51 lawyers.

A developing rift between Ankara and Rome illustrates what Turks can expect from the government-controlled and -aligned media: a moulding of the truth to fit the words and agenda of the country’s president.

In a combative interview with Italy’s RAI News 24, president Recep Tayyip Erdogan challenged the Italian government’s investigation of his son Bilal. He warned that the incident would put Turkey’s relations with Italy “in difficulty”.

“If my son had entered Italy, he would perhaps be arrested. What is this? My son, who is a bright man, is accused of money laundering. Instead of hassling my son, Italy should deal with its own mafia,” he said angrily.

His anger spilled over to the city of Bologna as well. “In that city they call me a dictator,” Erdogan said. “They organise pro-PKK demonstrations. Why don’t they [Italian authorities] step in? This issue will jeopardise our relations with Italy.”

Later, Italy’s prime minister, Matteo Renzi, responded on Twitter: ”In this country the judges respond to the laws and the Italian constitution, not the Turkish president. It’s called ‘rule of law.'”

It’s unnerving how this not-so-diplomatic sparring played out in the Turkish press. While Erdogan’s words were widely quoted on TV channels, the Italian prime minister’s reaction was missing. As media-monitoring organisations pointed out, half of reality was missing, self-censored by subservient outlets under the president’s thumb.

Erol Önderoğlu, Reporters Without Borders’ Turkey representative, asked via Twitter whether or not Turkish TV channels would consider reporting Renzi’s “rule of law” comments. Sadly, he knew they wouldn’t.

It goes further, though. As if self-censorship wasn’t enough, the government moved to block access to articles about the money laundering allegations against Bilal Erdogan following the RAI interview. Cumhuriyet — one of the handful of independent media outlets remaining — reported that Diken and Gazeteport — already under the eye of the government — were sites that had their coverage censored.

At the same time, behind the smokescreen of a subservient press, the Erdogan administration has turned its oppressive measures on Kurdish journalists. Police in the Karayazı District of Erzurum Province detained Mehmet Arslan, a reporter for Dicle News Agency (DİHA). Turkish telecommunications regulator, TIB, blocked access to the website of JİNHA news agency, which mainly covers Kurdish issues.

Journalists on social media were warning authorities that there was a high risk that a journalist in detention, Haşim Söylemez, who recently had two successive brain surgeries, could face health issues in jail.

A colleague of his, briefly arrested with Söylemez, tweeted that “he had a hard time even standing up in the cell”.

Önderoğlu is as deeply concerned as I am about the coming weeks. He said in next four months at least 149 journalists will be facing courts and, due to emergency rule practices, there will be many legal inquiries underway about the others, mainly based on the Anti-Terror Law and the Criminal Code.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

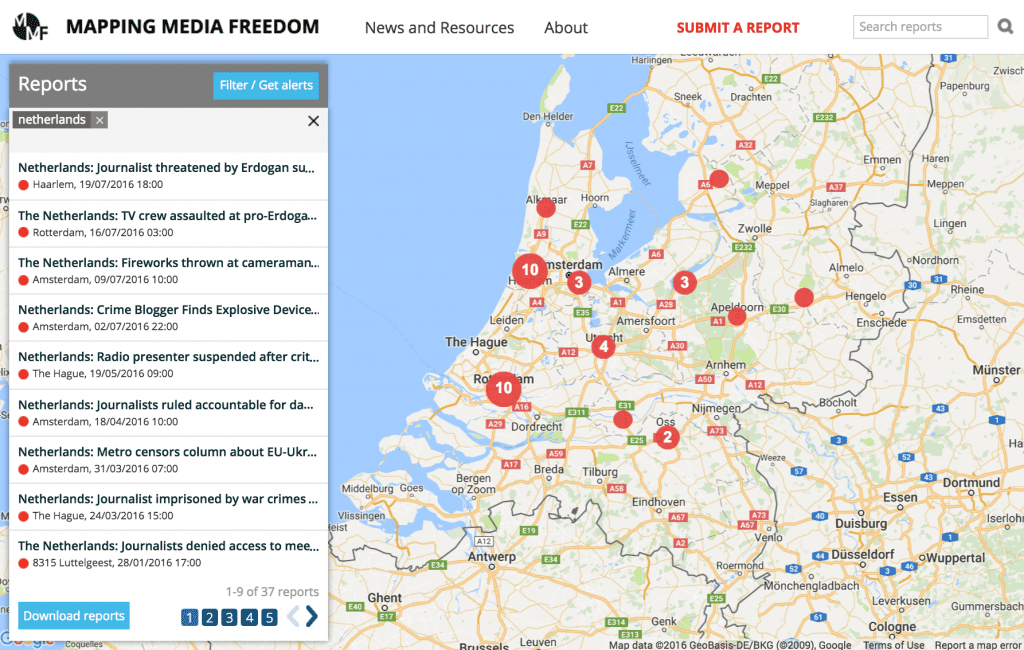

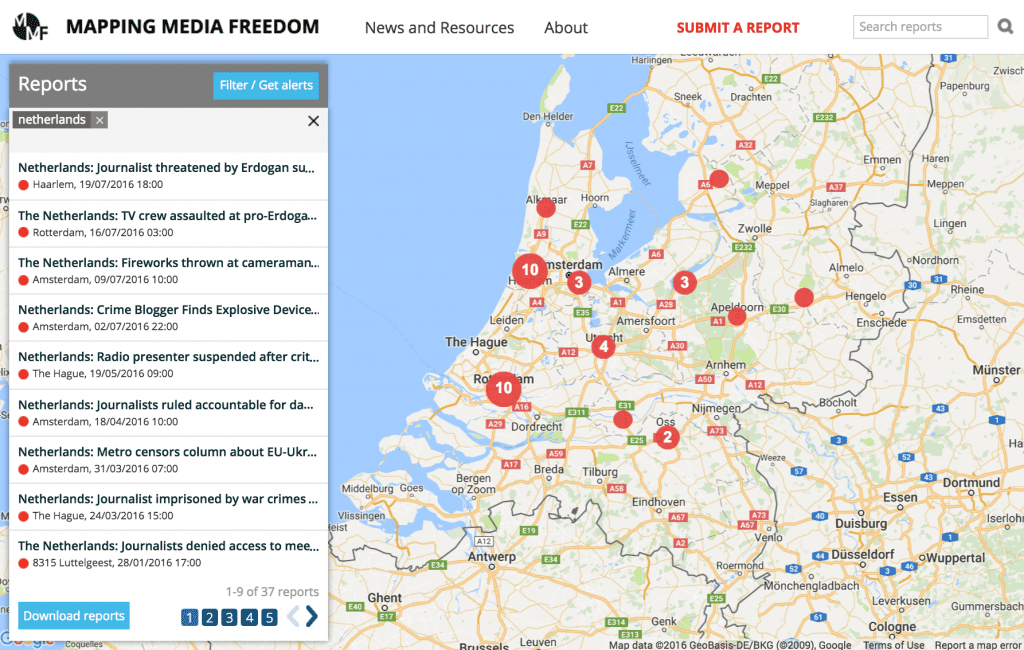

3 Aug 2016 | Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, Netherlands, News, Turkey

Following last month’s failed coup, journalists in Turkey are facing the largest clampdown in its modern history. Journalists covering the events from abroad have not escaped unscathed, including a number in the Netherlands who have faced threats and attacks.

Unusually, the journalists of the Rotterdam-based Turkish newspaper Zaman Today welcomed the increased police presence. Long before the military coup that failed to remove Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan from power, the government had been targeting journalists. But today a Dutch police officer drops by frequently to check if Zaman’s journalists are alright. It makes journalist Huseyin Atasever, who has been working for the Dutch Zaman since 2014, feel safe. Or at least safer than he has felt in a while.

On the morning of Tuesday 19 July Atasever was on his way to Amsterdam when he received a phone call. A Turkish-Dutch individual had been abused by Erdogan supporters at a mosque in the city of Haarlem. Atasever decided to go there immediately.

“I found a man sitting in a corner on the floor talking to the police,” he told Index on Censorship. “He was injured and his clothes were torn.”

After Atesaver had interviewed the victim, who had been targeted for being critical of Erdogan, he approached a group of Erdogan supporters nearby to hear their side of the story.

“When these men realised that I work for Zaman Today, things got grim,” Atasever said. “A few of them surrounded me and started shouting death threats at me. They told me ‘we will kill you, you are dead’.”

“Thanks to immediate police intervention I managed to get away unhurt,” he added.

More than ever before, Turks all over the world have seen their diaspora communities divided between supporters and critics of Erdogan.

At around half a million people, the Netherlands has one of the largest Turkish communities in Europe. In the days after the coup, thousands of Dutch Turks took to the streets in several cities to show their support for the Turkish president. Turks critical of the Erdogan government had told media that they’re afraid to express their opinions due to rising tensions.

People suspected of being supporters of the opposition Gulen movement, led by Erdogan’s US-based opponent and preacher Fethullah Gulen, which has been accused of being behind the coup attempt, have been threatened and physically assaulted in the streets. The mayor of Rotterdam, a city with a large Turkish community, urged Dutch-Turks to remain calm and ordered increased police protection of Gulen-aligned Turkish institutions.

The men who had threatened Atasever were arrested, but released shortly afterwards. Atasever said he has pressed charges against them. He still receives threats on social media every day: he has been called a traitor, a terrorist and a coup supporter on Twitter. His photo and contact details have been shared on several social network sites accompanied by messages like “he should be hanged” and “let’s go find him”.

On 1 August Zaman Today’s Dutch website was hit by a DDoS attack and knocked offline for about an hour. An Erdogan supporter reportedly had announced an attack on the website earlier via Facebook, and Zaman Today announced it will be pressing charges.

It hasn’t just been journalists of Turkish descent who have been attacked. During a pro-Erdogan demonstration at the Turkish Consulate in Rotterdam, a TV crew for the Dutch national broadcaster NOS was verbally harassed by a group of youth. NOS reporter Robert Bas told the network that his cameraman had been assaulted and their car was also damaged. “There’s a very strong anti-western media atmosphere here,” Bas said in a live TV interview at the scene.

The Dutch Union for Journalists (NVJ) is worried about growing intimidation of journalists in the Netherlands, NVJ chairman Rene Roodheuvel said in Dutch daily Trouw. “The political tensions at the moment in Turkey and the attitude towards journalists there may in no circumstance be imported into the Netherlands,” he said. “We are second in the world when it comes to press freedom. Media freedom is a great good in the Dutch democracy and it must always be respected.”

“AKP supporters believe that media, especially in the west, are part of an international conspiracy to overthrow Erdogan,” Atasever said. Being a journalist for Zaman Today, he is not new to receiving threats. Many Turks feel the Western media is “the enemy”, he explained. “But we are even worse because we are of Turkish descent. They see us as traitors of our country.”

The government took control of the Turkish edition of Zaman in March 2016. Zaman was a widely distributed opposition newspaper, and very critical of the Erdogan government. The paper had ties with Gulen, who has denied any involvement in the coup attempt, but the Turkish government accuses him a running a parallel government. Zaman and its English-language edition, Today’s Zaman, have since been turned into a pro-government mouthpiece.

Most of Zaman’s foreign editions, however, have so far avoided government control. Zaman has editions in different languages around the world. The Dutch edition, Zaman Vandaag, with a circulation of 5,000, has managed to keep its editorial independence.

While independent journalists in Turkey are being arrested one by one, journalists of Turkish descent in the Netherlands are starting to worry too. “I know for a fact that our names have been given to the Turkish government by Dutch AKP supporters, labelling us as traitors and enemies of the state,” said Atasever, who has no plans to travel to Turkey.

“If our names are on a wanted list, which I expect they are, we will be arrested as soon as we set foot in Turkey.”

1 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Turkish journalist Lale Kemal

It was a long Saturday night for all of us, at home and abroad, monitoring the worrisome developments around media freedom in Turkey. As if to confirm our fears, the night ended with the detention of six more journalists.

Defence lawyers expected the cases to be handled first thing Monday 1 August. But in a hasty move, journalists who wrote for the opinion section of Zaman — which stands at the epicentre of accusations of being part of the so-called “media leg of FETO terror organisation” — were taken to the Istanbul courthouse. After a long process, all were sent to jail.

The ruling, written under the extraordinary circumstances of emergency rule, reads like a severe restriction of the free word in particular and journalism in general.

The motivation for detention went, in a nutshell, that the six “prevented the investigation on the armed structure in their columns and via social media, and continued to write their columns even after the chief editor of Zaman daily, Ekrem Dumanlı, had fled the country”. Sigh.

There was no other mention than their expressed views — without going into any specifics in their content — and it was seen as sufficient by the judge to rule for jailing. Theirs will add to the pile of complaints from Turkey at the European Court of Human Rights.

It was the case of Şahin Alpay in particular which raised concerns among his colleagues in media and academia. One of the top liberal voices in Turkey, and known with respect among others in German social democrat, liberal and green political circles, Alpay is utterly frail with several health issues. The hopes of a release — albeit conditional — were high but crashed.

Yesterday, his family tried to contact him in prison, uncertain of any success.

All the six are from Turkish media’s liberal end of the spectrum. Among them are two female reporters that require attention. Lale Kemal, who was a commentator with Zaman, is an expert journalist on defence issues, with a long career. Her CV begins with Anatolian Agency, going on with Cumhuriyet daily, Hürriyet Daily News, Taraf and Today’s Zaman. She has been a stringer for Jane’s Defence Weekly for a long time.

The other, Nuriye Akman, has been a professional for 25 years. She worked with “mainstream” dailies in the 1990s and marked her reputation with long, Oriana Fallaci-style interviews both in print and TV. She is also the author of three novels.

Both women have been known to earn their keep only through journalism, like the others in this group of detainees.

Ali Bulaç, with a background as a theologue, is an independent voice within the conservative segments, often with disagreements and polemics with some others in the group. Ahmet Turan Alkan is regarded as a senior voice as part of the centre-right liberal flank in Turkey, popular for his ironic style. And Mustafa Ünal, who was Ankara Bureau Chief of Zaman, was for long active in Ankara, covering major political issues with a minimalist, simple writing style.

According to the regular monitoring done in daily basis by Platform for Independent Journalism (P24), these latest detentions mean that since the bloody coup attempt on July 15, 29 journalists are detained. In a total, there are now 62 journalists in jail in Turkey.

During the long, dark hours on Sunday, there was another message that added to the fears. A colleague, Ali Aslan, based in Washington DC, tweeted that the police had detained the wife of a journalist Bülent Korucu, former editor in chief of the weekly news magazine Aksiyon, now under arrest warrant but on the run. The police, Aslan claimed, threatened to keep her locked until her husband surrenders. Korucu’s son also confirmed this claim.

Dark Sunday indeed.

What fuels the concerns is that there is so far no assurance from the government about the respect for media freedom and whether or not the witch hunt will end anytime soon.

A version of this article originally appeared at Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.