Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

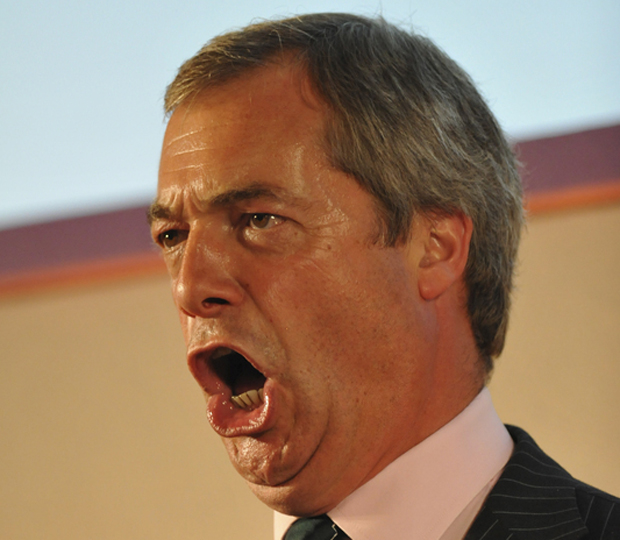

(Photo: Michael Preston / Demotix)

Ofcom’s decision to declare the UK Independence Party a ‘major party’ for the purposes of this month’s European elections has led to questions about who should be allowed to address the public. Behind the scenes, broadcasters have asked why their right to editorial freedom is restricted at all.

UKIP’s leader, Nigel Farage, responded: “This ruling does not cover the local elections, despite UKIP making a major breakthrough in the county elections last year. This strikes me as wrong.”

Natalie Bennett, leader of the Green Party – which Ofcom decided was not a major party – pointed out that, unlike UKIP, her party has an MP, and is also “part of the fourth-largest group in the European Parliament”.

Both sides pounced on the Liberal Democrats, whose dwindling position in the polls, they hinted, should see it demoted to minor party status.

The decision means commercial TV channels that show party election broadcasts must allow UKIP the same number of broadcasts as the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats. They will also be given equal weight in relevant news and current affairs programming. However, for content focusing on, or broadcasting solely to, Scotland, UKIP’s lower levels of support there mean it will remain a minor player.

This of course gives UKIP a certain level of legitimacy, and the scope to influence even more voters. For those campaigning against them, the move is grossly unfair.

The Green Party in particular feels hard done by. From the House of Lords to local councils it has representatives at every level, but Ofcom still claims it hasn’t achieved enough. Yet in its report the regulator said that it could not make UKIP a major party in Scotland without granting the same status to the Scottish Green Party, due to their comparable performance.

Ofcom has promised to review the list periodically, so things could change in future. But for now it believes the list represents political realities. UKIP’s focus on getting Britain out of Europe has helped it to do well at the past few European elections. In 2009 it came second in terms of vote share, up from third place in 2004, and this year a number of polls indicate that it could win. In more recent local elections UKIP has done well, achieving 19.9 per cent of the total vote in 2013. But this has leapt up from 4.6 per cent in 2009’s local elections, which for Ofcom is not consistent enough to justify extra coverage for its prospective councillors.

So it seems fair enough that UKIP counts as an important party for Britain in the European Parliament. The Greens are yet to win enough votes in enough elections for their inclusion to make sense. And the Liberal Democrats appear to be clinging on only because of their level of support in past general elections, which was also taken into account.

But the real question is why a list is necessary at all. After all a “regulated free press” sounds something like “freedom in moderation” – ultimately a nonsense. Ofcom’s control over which parties receive coverage puts a dampener on broadcasters’ right to freedom of expression and makes it more difficult for newer parties to break through.

Responding to a previous consultation on whether the list of major parties should be reviewed, Channel 4 said the regulator’s rules should “ensure that political messages are conveyed in a democracy… [but] such regulation should be as narrow as possible to restrict… any interference with the broadcaster’s right to editorial independence and its rights to freedom of expression”. Channel 5, meanwhile, said the concept of major parties did not have “continuing relevance at a time of increasing political flux and fragmentation within the electorate”.

Ofcom appears to be prioritising the need of the electorate to be informed. So it could be argued that, for the purposes of allocating party election broadcasts, the list is useful to prevent any channel from steadfastly omitting information on a party that is likely to appear on most voters’ ballot papers.

But in terms of news and current affairs programming, there seems little reason that broadcasters shouldn’t have the freedom to say what they please – particularly because newspapers are faced with no such restrictions.

As the dominance of mass media fades, and the internet provides access to alternative points of view, the restrictions on the news you receive through your TV will only become more obvious.

This article was originally published on April 30, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org