27 May 2014 | News, Politics and Society, Ukraine

Petro Poroshenko at a polling station (Photo: Oleksandr Ratushniak/Demotix)

Petro Poroshenko has won the Ukrainian presidential election in the first round, as preliminary results and exit polls show he received over 50% of votes. A billionaire, sometimes dubbed “the Chocolate Oligarch” (his main asset is Roshen, the largest confectionery manufacturer in Ukraine) gained his popularity during the Euromaidan protests in November 2013 – February 2014. Many in Ukraine consider Poroshenko to be a controversial figure as the head of the country; he represents a revolutionary, pro-European, but still old, oligarch-driven elite, and a system the Euromaidan protests were aimed against. Yet, the huge support he received shows Ukrainians are tired of the period of uncertainty, and united to give their country a new legitimate leader who can deal with unrest in the south-east regions, where pro-Russian militants continue their attempts to destabilise the situation.

Poroshenko’s first-round victory is a sign of national agreement, but is hardly a final remedy for all the problems Ukraine faces, both externally — like the military threat from Russia, including the occupation of Crimea — and internally. The latter applies not only to economic difficulties, but also to the necessity of extensive reforms that deal with the whole system of interrelations between the state and the society, ensuring real rule of law and putting end to corruption and human rights abuses.

Events in Ukraine over the last six months have made the country one of the most dangerous places for journalists in the world. According to the Institute of Mass Information, there have been 218 cases of physical attacks against reporters in Ukraine in 2014. Viacheslav Veremiy, a reporter for Ukrainian Vesti newspaper, was shot during events on Maidan on 19 February. Vasily Sergiyenko, a journalist and a civic activist, was tortured and then killed in Cherkassy in April. The death toll continued to rise even on the eve of the election, as Andrea Rocchelli, an Italian photo reporter, and his interpreter Andrei Mironov, a Russian human rights activist and a Soviet-era political prisoner, were killed on 24 May near Slovyansk, in the Donetsk region.

“It is still difficult to say if the free speech situation will improve after the election, especially in the east of Ukraine. It will depend on effectiveness of work of the new president and development of relations with Russia,” Tetiana Pechonchyk, the head of the Human Rights Information Centre, told Index on Censorship.

But it is not only the areas of military conflict that are dangerous for journalists. Sergiyenko’s murder and the case of Evgen Polozhiy, the editor of Panirama newspaper from Sumy, who was severely beaten, show reporters’ work is becoming increasingly risky business in Ukraine.

“There were quite a number of journalistic investigations before the Euromaidan, but they led to no official reaction or criminal cases about corruption revealed. Now that the society has changed, corrupt officials and criminals are especially afraid of critical reporting as they can lose their positions or even go to prison; they choose different methods to silence investigative journalists,” Pechonchyk says.

Another important aspect of a media reality around events in Ukraine is the massive information war, launched by Russia. The aim is to show a distorted picture of a modern Ukraine as a state where right-wing extremists and “fascists” seized power, in spite of the fact that the leader of the notorious “Right Sector” organisation got less than 1% of votes during the presidential election. They also aim at perplexing the foreign audience by mixing the terms “Russian-speaking” and “Russian”, for instance to justify invasion of Crimea or actions of pro-Russian militants in Donetsk region.

“That’s what you expect Russia to do — blow the country over with lots of stereotypes, lies and myths. Unfortunately, the Ukrainian government lost this information war. But what is great is that civil society, bloggers, ordinary young people on Facebook confronted Putin’s lies with their activity and creativity, with websites that disprove Russian TV channels’ propaganda or fake news,” says Michael Andersen, a journalist who made a documentary for Al Jazeera about typical stereotypes around Ukraine and Ukrainians.

The latter still have a long way to go to ensure the Maidan changes a lot more than just the name of the president and the faces of the governmental officials. Civil society and the media have a vital role to play on this path to future reforms.

This article was published on May 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

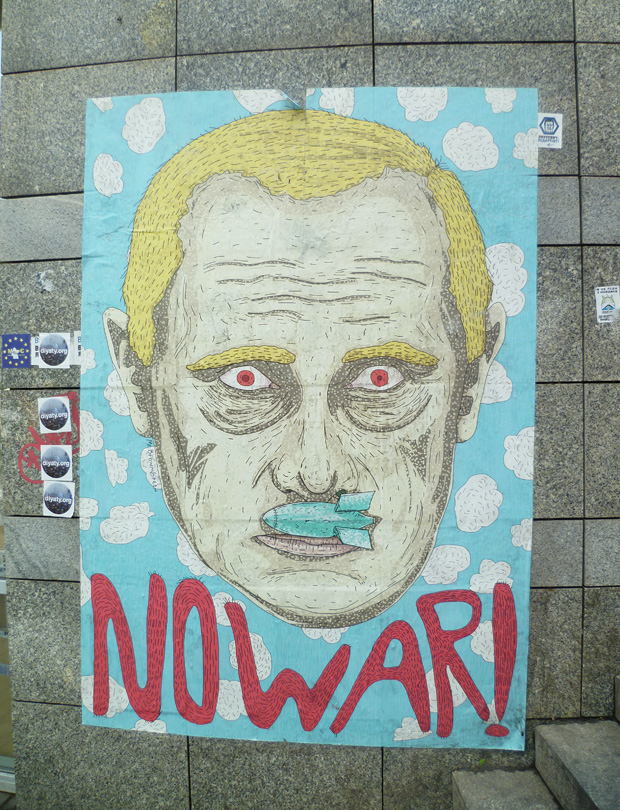

23 May 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Ukraine

(Image: Index on Censorship)

Ukraine is seeing a “concerning pattern of grave violations of media freedom commitments” warns OSCE press freedom boss Dunja Mijatovic in a new report.

“As we know too well, in times of crisis and conflict, journalists and members of the media are among the first to be attacked, both physically and psychologically. Because those in power during periods of conflict demand complete control of all information free media is often their first target,” the report, published on Friday, states. Covering the time between 28 November 2013 and 23 May 2014, these are the three key findings.

1) Journalists face serious threats to their safety

There have been “nearly 300 reported cases of violence against journalists, including murder, physical assaults, kidnappings, threats, intimidations, detentions, imprisonments, and damage and confiscation of equipment”. These attacks are divided into two phases — the first covering the Maidan protests in Kiev, and the second the ongoing crisis in the east of the country. In Maidan, journalist Viacheslav Veremyi was killed, while almost 200 others were victims of violence. These include the over 40 journalists who were assaulted while covering protests on 13 December 2013. “In some cases,” the report states, “journalists were specifically targeted by law enforcement despite displaying clear identification as members of the press.” Since March, attacks on journalists in the east have intensified and gone without prosecution — something that “points to the breakdown of the rule of law in the parts of Ukraine affected by conflict”. On 18 May, Ukrainian military arrested two Russian journalists from LifeNews, while two journalists from Otkritiy Krymskiy Kanal were detained, interrogated, beaten and had their equipment seized by a group of people wearing military uniforms. Journalists in Crimea — recently annexed by Russia — who are not considered loyal to the region’s authorities, and who refuse to change citizenship, have been faced with regular threats, harassment and the possibility of eviction.

2) Ukraine is in the middle of an information war

There have been a number of accusations of the media being used to disseminate propaganda. “Propaganda and the deterioration of media freedom combine to fuel and contribute to the escalation of conflict, and once it starts they contribute to its escalation,” the report states. Among other thing, broadcasting stations “and related infrastructure” in Crimea, Sloviansk, Donetsk and Luhansk, have been attacked by unidentified and often armed individuals who supplanted regularly scheduled television programming with Russian state media. In March, the National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council of Ukraine ordered all cable operators to stop broadcasts of several Russian state TV channels. “No matter how loud and outrageous certain voices are, they will not prevail in a competitive and vibrant marketplace of ideas,” the report argues. “Therefore, any potentially problematic speech should be countered with arguments and more speech, rather than engaging in censorship.”

3) Media workers are being denied entry

In the past months, the OSCE has intervened in some 30 cases of journalists being denied entry into Ukraine and Crimea. “I have serious concerns about excessive restrictions on such travel, which ultimately affects the free flow of information and free media,” writes Mijatovic. Recently, Russia Today’s Arabic news crew, who travelled to Kiev to cover Sunday’s presidential election, were denied entry at immigration. Two crews from the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company (VGTRK) were not allowed to enter Ukraine, despite having all required accreditations. On a related note, a Rossiya-1 TV crew were this week deported from Ukraine.

This article was posted on May 23, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

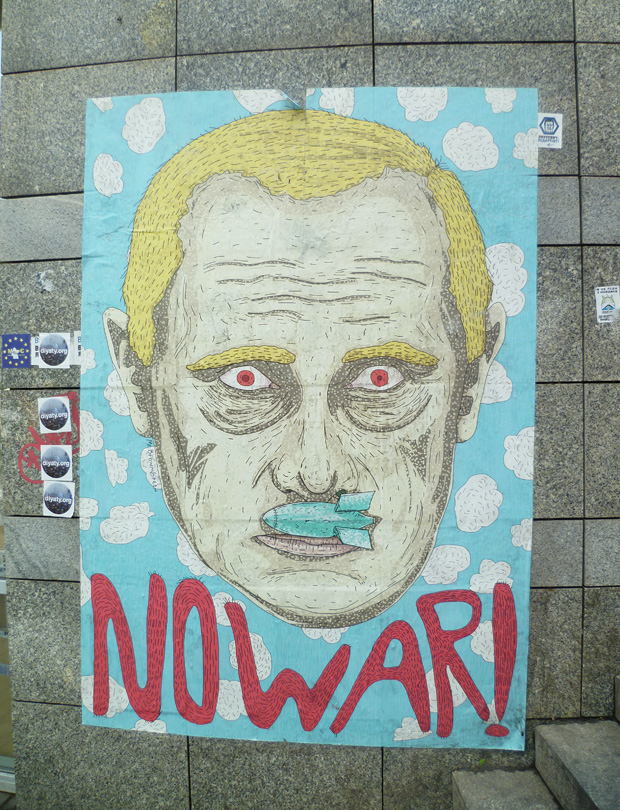

22 May 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, Politics and Society, Ukraine

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

Walking around Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti square, months after the protest that enveloped the city and toppled the corrupt government of Viktor Yanukovych died down, is a strange experience. International attention has understandably shifted, the images now beamed across the world are from the ongoing crisis in eastern Ukraine. The capital is calm these days, so I don’t know exactly what I was expecting as I made my way down Mykhailivska street.

Tents still populate Maidan, with young and old lounging, talking and cooking in the May sunlight. I walked past sandbag barricades, and ones made of tyres painted in the blue and yellow of the Ukrainian flag. There were flags were everywhere — EU, American, British, and many more. I walked past the independence monument, juxtaposed against the new year tree, covered by protesters in posters, and yet more flags. Music was blaring out from the small stage facing these towering structures. The lyrics I couldn’t understand, apart from the cry of “Ukraina” in the chorus. I made my way past the Maidan press centre, towards a bridge which had a large banner emblazoned with names and faces hanging from it. The Hotel Ukraina behind me, I looked out over the square.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

The only thing missing was the crowds. It felt like they had just taken a break — gone for lunch, to return at any moment. Perhaps I arrived with a naive “out of sight, out of mind”, mentality, subconsciously assuming that the square would to an extent have been cleared out. But Maidan seems to be, for now at least, a living monument to the profound change, and crisis, Ukraine is going through.

It was against this backdrop, and with the country’s general elections set for this Sunday, I travelled to Kiev to take part in the conference Ukraine: Thinking Together. The brainchild of Yale University history professor Timothy Snyder and the New Republic’s Leon Wieseltier, its purpose was “to meet Ukrainian counterparts, demonstrate solidarity, and carry out a public discussion about the meaning of Ukrainian pluralism for the future of Europe, Russia, and the world.” The guest list included academics like Bernard-Henri, Lévy Timothy Garton Ash and Ivan Krastev, and journalists like The New York Times’ Roger Cohen and The Atlantic’s David Frum. Former Swedish prime minister Carl Bildt also made an appearance at the welcome reception.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

One could question what, if any, effect the discussions of a group of intellectuals might have on the very real crisis on the ground. Over the weekend, there were among other things, a Crimean Tartar journalist was detained in Simferopol, while the Ukrainian military arrested two Russian reporters. But Kiev-based journalist Maxim Eristavi told me, and tweeted, that it was “surreal” to have the “intellectual powerhouse of the West in one room in Kyiv”. If nothing else, organising a big-name gathering to talk about Ukraine, in Ukraine, makes a bold statement — and one likely to be heard all the way to Moscow.

A range of topics were tackled in five days of panel debates and public lectures. The Maidan protest was applauded, with Wieseltier in his opening remarks calling it “one of the primary sites of the modern struggle for democracy”. Carl Gershman, President of the National Endowment for Democracy, called Maidan a geopolitical move, but by a people rather than a government.

(Image: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

Bernard-Henri Lévy spoke of his recent visits to eastern Ukraine, explaining that while they might be fewer than in the Maidan, there are people in these areas who support a unified Ukraine. He contested what he believed to be the image presented in western media that people in the east are all separatists. While the point was made that flags, national symbols and the Maidan movement is not perceived as positively in all parts of the country as in Kiev, Constantin Sigov, professor at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla, argued that the Ukrainian crisis is first and foremost civil and political, not one of identity.

Russia’s foreign policy and Russian President Vladimir Putin were unsurprisingly recurring themes. “He has values. They are not our values, but they are values,” said François Heisbourg, chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, talking on the panel of geopolitics after Crimea. Writer Paul Berman argued, in the same panel, that Putin is acting from a position of weakness, and fear that Russia is not stable. Others, meanwhile, were uncomfortable with the term geopolitics, saying it legitimises Putin’s world view.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

Russia’s propaganda strategy was also a hot topic and elicited strong responses, with one audience member referring to it as a weapon of mass destruction. “Propaganda is the beginning of bloodshed, it precedes bloodshed,” said Alexandr Podrabinek, editor-in-chief of Prima information agency, on the panel discussing whether rights make us human. State-run news channel RT, formerly Russia Today, got several mentions. Academic Anton Shekhovtsov argued that RT gives space to democratic consensus in its coverage, but also to left-wing, far right and libertarian narratives, and even conspiracy theories. Because each is treated in roughly the same way, the democratic narrative becomes just one of many. He said this explains why RT appeals to some people in the west, but stressed that they’re pushing an overall Russian agenda.

Podrabinek, despite dubbing RT “hateful”, argued that while there might be a temptation to shut down views we don’t like, this is not a good way of confronting them. If we want freedom of expression, he said, we can’t do that. On a related note, Carl Gersham argued that while Ukraine needs to be supported economically and militarily, they also need support in modernising the media landscape, to foster internal dialogue.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

And while the regime was criticised by speaker after speaker, ordinary Russians and their rights were not forgotten. Sergei Lukashevsky, director of the Sakharov Museum and Public Centre, put the support for Putin into the context of fear. When people see that the state is cracking down on human rights again, he argued, they make themselves fit in — go into survival-mode. While rights exist formally in Russia, he explained the practical situation through an old Soviet joke: “Do I have the right? Yes. Can I? No.”

In a weekend of intellectuals discussing how to solve a crisis, novelist and non-fiction writer Slavenka Drakulic gave a sobering lecture on the role of intellectuals in causing crises, specifically the Balkan wars. To be able wage war, to kill, you have to create an enemy and dehumanise it, she argued. Here is where academics, poets, journalists came in handy in former Yugoslavia — by preparing people psychologically for conflict, “using words almost like bullets”.

(Photo: Milana Knezevic/Index on Censorship)

And this leads well into the final panel of the conference, on the role of history and memory in politics, the difference between official history and collective and personal memories of the people, and how especially the former can be manipulated. We’re arguably seeing that today already, with Timothy Snyder saying that with events in Ukraine, a European revolution is being contested even as it’s happening. The Russian Ministry of Education is already writing new chapter to explain Crimea, said acclaimed Ukrainian novelist Andrey Kurkov. “And Ukraine might have their version.”

After my trip to Maidan, I asked a Ukraine-based AP journalist what the future might bring for the square. There are only a specific type of people still there, she explained, and they might see how the elections go before they decide to stay or leave.

Or as Myroslav Marynovych, the founder of Amnesty International Ukraine, said during the conference — when there is democracy, there will be no need to go to Maidan.

This article was published on May 22, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org