Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Graffiti of Vladimir Putin. Photo: Don Fontijn/Unsplash

I have struggled to write this blog. There don’t seem to the right words for something so serious, so terrifying but so utterly predictable.

Putin has invaded Ukraine – again.

As I write there are Russian bombs falling across Ukraine. Innocent people are dying, families are sheltering from bombing raids in the underground and people are fleeing.

This act of war, from a tyrant, cannot be explained or excused. This is an effort to destabilise Europe. To re-build a Russian Empire. To secure Putin’s legacy. It is not about NATO expansionism or a security threat from Ukraine. This is all Putin. This is not about the Russian or Ukrainian people.

Putin has brought war and death to mainland Europe and the world is more unstable than at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis. That is our shared reality in 2022. This is the consequence of allowing a dictator to operate unchecked as readers of our work at Index know only too well.

Index does not exist to pontificate about international relations and defence policy – as frustrated as we may be. Our role, always, is to provide a space and a voice for dissidents and those being persecuted. But, and it’s a big but, we were founded in the midst of the Cold War half a century ago – to promote and protect the liberal democratic value of free expression. To work behind the Iron Curtain to provide a platform for the work and personal reflections of dissidents. We did this because we believe in democracy. That the foundations of free expression are protected at the ballot box. That the ultimate expression of freedom is the right to self-determination and to peace in a free society.

The invasion of Ukraine brings to the fore the reasons why Index exists. Even in the early hours and days of this aggression we have seen misinformation used as a propaganda tool. Journalists in Russia have been instructed to only use official comment on events in Ukraine. Protesters against the war in Moscow are being arrested in the dozens. And DDoS attacks on Ukrainian cyber infrastructure is becoming the norm. Putin is seeking to control every form of communication – that is not free speech.

In the months and years ahead Index will continue to provide a platform for dissidents. We will tell the stories of those writers, artists and academics who are being silenced by Putin’s regime. We will do what we do best – be a voice for the persecuted.

But as scared as I am of events in Eastern Europe – I worry about censorship through noise (as so ably articulated by Umberto Eco) that we are about to live through. Every repressive government could move against their citizens in the coming months with little global condemnation as our world leaders seek to find peace and secure the world as we know it. As we have for over half a century Index will be a home for those dissidents too – wherever they live – highlighting their stories and publishing their work.

The months ahead are going to be awful for too many people. Tyrants will believe they have a free hand to move against their citizens. Europe faces more war and the Chinese Communist Party may well seek to manipulate events to suit themselves.

In this unstable world the work of Index has never been more vital and we will do everything we can to support those who need us most.

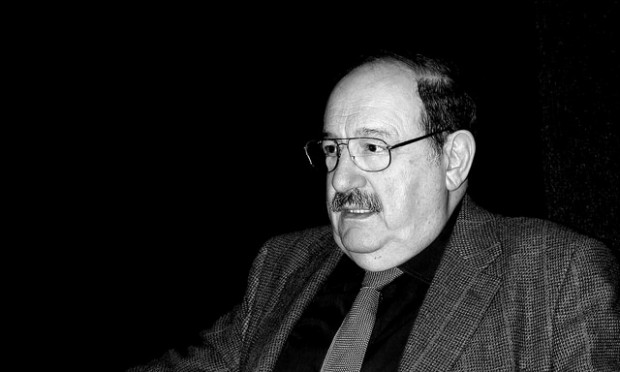

Umberto Eco, March 2010, Paris. Credit: Flickr / Abderrahman Bouirabdane

I am of the firm belief that even those who do not have faith in a personal and providential divinity can still experience forms of religious feeling and hence a sense of the sacred, of limits, questioning and expectation; of a communion with something that surpasses us.What you ask is what there is that is binding, compelling and irrevocable in this form of ethics.

I would like to put some distance between myself and the subject. Certain ethical problems have become much clearer to me by reflecting on some semantic problems – don’t worry if people say this discourse is difficult; we are perhaps encouraged into easy thinking by the ‘revelations’ of the mass media, which are, by definition, predictable. Let people learn to ‘think difficult’ because neither the mystery nor the evidence are easy to deal with.

My problem was whether there were ‘semantic universals’, or basic concepts common to all humanity that can be expressed in all languages. Not so obvious a problem once you realise that many cultures do not recognise notions that seem obvious to us: for example, that certain properties belong to certain substances (as when we say ‘the apple is red’) or concepts of identity (a=a). I became convinced that there certainly are concepts common to all cultures, and that they all refer to the position of our body in space.

The article is available for free until the end of March. To read it in full, click here.