Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

There has been significant commentary on the flaws of the Online Safety Bill, particularly the harmful impact on freedom of expression from the concept of the ‘duty of care’ over adult internet users and the problematic ‘legal but harmful’ category for online speech. Index on Censorship has identified another area of the Bill, far less examined, that now deserves our attention. The provisions in the Online Safety Bill that would enable state-backed surveillance of private communications contain some of the broadest and powerful surveillance powers ever proposed in any Western democracy. It is our opinion that the powers conceived in the Bill would not be lawful under our common law and existing human rights legal framework.

Index on Censorship has commissioned a legal opinion by Matthew Ryder KC, an expert on information law, crime and human rights, and barrister, Aidan Wills of Matrix Chambers. This report (a) summarises the main legal arguments and analysis; (b) provides a more detailed explanation of the powers contained in Section 104 notices; and (c) lays out the legal opinion in full.

The legal opinion shows how the powers conceived go beyond even the controversial powers contained within the Investigatory Powers Act (2016) but critically, without the safeguards that Parliament inserted into the Act in order to ensure it protected the privacy and the fundamental rights of UK citizens. The powers in the Online Safety Bill have no such safeguards as of yet.

The Bill as currently drafted gives Ofcom the powers to impose Section 104 notices on the operators of private messaging apps and other online services. These notices give Ofcom the power to impose specific technologies (e.g. algorithmic content detection) that provide for the surveillance of the private correspondence of UK citizens. The powers allow the technology to be imposed with limited legal safeguards. It means the UK would be one of the first democracies to place a de facto ban on end-to-end encryption for private messaging apps. No communications in the UK – whether between MPs, between whistleblowers and journalists, or between a victim and a victims support charity – would be secure or private. In an era where Russia and China continue to work to undermine UK cybersecurity, we believe this could pose a critical threat to UK national security.

The King’s Counsel’s legal opinion includes that:

● Section 104 notices amount to state-mandated surveillance because they install the right to impose technologies that would intercept and scan private communications on a mass scale. The principle that the state can mandate the surveillance of millions of lawful users of private messaging apps should require a much higher threshold of legal justification which has not been established to date. Currently this level of state surveillance would only be possible under the Investigatory Powers Act if there is a threat to national security.

● Ofcom will have a wider remit on mass surveillance powers of UK citizens than the UK’s spy agencies, such as GCHQ (under the Investigatory Powers Act 2016). Ofcom could impose surveillance on all private messaging users with a notice, underpinned by significant financial penalties, with less legal process or protections than GCHQ would need for a far more limited power.

● Questionable legality: The proposed interferences with the rights of UK citizens arising from surveillance under the Bill are unlikely to be in accordance with the law and are open to legal challenge.

● Failure to protect journalists: if enacted, journalists will not be properly protected from state surveillance risking source confidentiality and endangering human rights defenders and vulnerable communities.

The disproportionate interference with people’s privacy identified by the legal analysis paints an altogether different picture of the Online Safety Bill. Far from being a law to establish accountability for online crime, the legislation, as drafted, opens the door for sweeping new powers of surveillance with little public debate over their purpose and proportionality. Unless the government reconsiders or parliament pushes back, these powers are set on a collision course with independent media and journalism as well as marginalised groups.

Download this new legal opinion on the Online Safety Bill here

29 November 2022

To the Rt. Hon. Dominic Raab MP

Deputy Prime Minister and Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice

Copies sent to:

Rt. Hon. Dominic Raab, Deputy Prime Minister and Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice

Rt. Hon. Rishi Sunak MP, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

Rt. Hon. Michelle Donelan MP, Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

Rt. Hon. James Cleverly MP, Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs

Mr. Steve Reed MP, Shadow Labour Secretary of State for Justice

Rt. Hon. Alistair Carmichael MP, Liberal Democrat Spokesperson for Home Affairs, Justice and Northern Ireland

Ms. Anne McLaughlin MP, Shadow SNP Spokesperson (Justice)

Mr. John Penrose MP, UK Government Anti Corruption Champion

Mr. Paul Philip, Chief Executive, Solicitors Regulation Authority

Mr. Mark Neale, Director-General, The Bar Standards Board

Ms. Dunja Mijatović, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights

Ms. Teresa Ribeiro, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, Representative on Freedom of the Media

Ms. Irene Khan, United Nations Special Rapporteur on on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression

Re: Adoption of a UK Anti-SLAPP Law

As a group of leading editors, journalists, publishers, lawyers and other experts, we are writing to express our support for the Model UK Anti-SLAPP Law launched this November by the UK Anti-SLAPP Coalition – and to urge you to move swiftly to enshrine these proposals in law.

Events over the past year have shone a light on the use of abusive lawsuits and legal threats to shut down public interest speech. This is a problem that has long been endemic in newsrooms, publishing houses, and civil society organisations. In an age of increasing financial vulnerability in the news industry, it is all too easy for such abusive legal tactics to shut down investigations and block accountability.

We welcome your commitment to bring in reforms to address Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs), as you said on 20 July 2022, in order to “uphold freedom of speech, end the abuse of our justice system, and defend those who bravely shine a light on corruption.” High-profile cases – such as those targeting Catherine Belton, Tom Burgis, Elliot Higgins, and more recently openDemocracy and The Bureau of Investigative Journalism – are just the most visible manifestation of a much broader problem which has affected newspapers across Fleet Street and the wider UK media industry for many years.

The public interest reporting targeted by SLAPPs is vital for the health of democratic societies, including law enforcement’s ability to investigate wrongdoing promptly and effectively. This is of acute importance in the UK, which journalistic investigations have repeatedly shown to be a hub for illicit finance from kleptocratic elites. As of April 2022, the National Crime Agency (NCA) has estimated the scale of money laundering impacting the UK is in excess of £100bn a year.

Journalism has a huge role to play in tackling this problem. For example, investigations by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) into the ‘Azerbaijani Laundromat’ scandal supported the NCA in seizing millions in corrupt funds from a number of individuals, including £5.6 million from members of one Azerbaijani MP’s family. Prior to the NCA’s seizure, the same MP had spent two years pursuing Paul Radu, co-founder of OCCRP through London’s libel courts. The inequality of arms in such cases is clear. As Radu notes: “The people suing journalists in the UK rely on these huge legal bills being so intimidating that the journalists won’t even try to defend themselves.”

In March 2022, at the launch of the Government consultation on SLAPPs, you stressed that “The Government will not tolerate Russian oligarchs and other corrupt elites abusing British courts to muzzle those who shine a light on their wrongdoing.” The findings of the consultation, published in July, clearly stated that “the type of activity identified as SLAPPs and the aim of preventing exposure of matters that are in the public interest go beyond the parameters of ordinary litigation and pose a threat to freedom of speech and the freedom of the press.”

Fortunately, there is an oven-ready solution to this problem. The Model Anti-SLAPP Law, drafted by the UK Anti-SLAPP Coalition in consultation with leading media lawyers and industry experts, would provide robust protection against SLAPPs, building on the framework proposed by the Ministry of Justice in July. Key features include:

The need could not be more urgent. Research by the Foreign Policy Centre and other members of the UK Anti-SLAPP Coalition has found that SLAPPs are on the rise and that the UK is the number one originator of abusive legal actions. In fact, the UK has been identified as the leading source of SLAPPs, almost as frequent a source as all European Union countries and the United States combined.

The EU has already taken steps, with a proposed Anti-SLAPP Directive announced in April. In the US, 34 US states already have anti-SLAPPs laws in place, and this year Congress has introduced the first federal SLAPP Protection Act. Moreover, the US has also launched the Defamation Defense Fund, recognising the impact SLAPP actions have on journalists, as they “are designed to deter them from doing their work.”

You have made clear your commitment to strengthening legal protections against these legal tactics. It is crucial momentum is not lost. We encourage you to put forward, in the earliest possible time frame, legislation in line with the model UK Anti-SLAPP Law, to ensure that the UK can keep pace and contribute to this global movement to protect against SLAPPs.

Yours,

John Witherow, Chairman, Times Media

Emma Tucker, Editor, The Sunday Times

Tony Gallagher, Editor, The Times

Victoria Newton, Editor-in-Chief, The Sun

Paul Dacre, Editor-in-Chief, DMG media

Ted Verity, Editor, The Daily Mail

Katharine Viner, Editor-in-Chief, The Guardian

Paul Webster, Editor, The Observer

Alison Phillips, Editor, The Mirror

Oliver Duff, Editor-in-Chief, i

Roula Khalaf, Editor, The Financial Times

Chris Evans, Editor, The Telegraph

Alan Rusbridger, Editor, Prospect Magazine

Ian Hislop, Editor, Private Eye

Zanny Minton Beddoes, Editor-in-Chief, The Economist

Alessandra Galloni, Editor-in-Chief, Reuters News Agency

John Micklethwait, Editor-in-Chief, Bloomberg

Drew Sullivan, Co-founder and Publisher, Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP)

Paul Radu, Co-founder and Chief of Innovation, OCCRP

Rozina Breen, CEO, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ)

Peter Geoghegan, Editor-in-Chief and CEO, openDemocracy

Nick Mathiason, Co-founder and Co-director, Finance Uncovered

Gerard Ryle, Director of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ)

David Kaplan, Executive Director, Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN)

Michelle Stanistreet, General Secretary, National Union of Journalists (NUJ)

Dawn Alford, Executive Director, Society of Editors

Sayra Tekin, Director of Legal, News Media Association (NMA)

Sarah Baxter, Director, Marie Colvin Center for International Reporting

Paul Murphy, Head of Investigations, Financial Times

Rachel Oldroyd, Deputy Investigations Editor, The Guardian

Carole Cadwalladr, journalist, The Observer

Catherine Belton, journalist and author of the book, Putin’s People: How the KGB took back Russia and then took on the west

Tom Burgis, reporter and author of the book, Kleptopia: How dirty money is conquering the world

Oliver Bullough, Journalist and author

Clare Rewcastle Brown, investigative journalist and founder of The Sarawak Report

Richard Brooks, journalist, Private Eye

Matthew Caruana Galizia, Director of The Daphne Caruana Galizia Foundation

Mark Stephens CBE, Partner at Howard Kennedy LLP

Caroline Kean, Consultant Partner, Wiggin

Matthew Jury, Managing Partner, McCue Jury and Partners

David Price KC

Rupert Cowper-Coles, Partner at RPC

Conor McCarthy, Barrister, Monckton Chambers

Pia Sarma, Editorial Legal Director, Times Newspapers Ltd

Gill Phillips, Director of Editorial Legal Services, Guardian News & Media

Lisa Webb, Senior Lawyer, Which?

Juliette Garside, Deputy Business Editor, The Guardian and The Observer

Alexander Papachristou, Executive Director of the Cyrus R. Vance Center for International Justice

José Borghino, Secretary General, International Publishers Association

Dan Conway, CEO, Publishers Association

Arabella Pike, Publishing Director, HarperCollins Publishers

Joanna Prior, CEO of Macmillan Publishers International Limited

Meirion Jones, Editor, TBIJ

Emily Wilson, Bureau Local Editor, TBIJ

James Ball, Global Editor, TBIJ

Franz Wild, Enablers Editor, TBIJ

James Lee, Chair of the Board, TBIJ

Stewart Kirkpatrick, Head of Impact, openDemocracy

Moira Sleight, Editor, the Methodist Recorder

Paul Caruana Galizia, reporter, Tortoise

Tom Bergin, journalist and author

James Nixey, Director, Russia and Eurasia Programme, Chatham House

Edward Lucas, Author, European and transatlantic security consultant and fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA)

Sean O’Neill, Senior Writer, The Times

Dr Peter Coe, Associate Professor in Law, Birmingham Law School, University of Birmingham

Alex Wilson, Partner at RPC

George Greenwood, Investigations Reporter, The Times

Simon Bowers, Investigations Editor, Finance Uncovered

John Heathershaw, Professor of International Relations, University of Exeter

Tena Prelec, Research Fellow, DPIR, University of Oxford

Thomas Mayne, Research Fellow, DPIR, University of Oxford

Jodie Ginsberg, President, Committee to Protect Journalists

Dr Julie Macfarlane, Co-Founder, Can’t Buy My Silence campaign to ban the misuse of NDAs

Zelda Perkins, Co-Founder, Can’t Buy My Silence campaign to ban the misuse of NDAs

One of the core tenets of media freedom is the ability to speak truth to power, to hold decisionmakers and political leaders to account. At Index we see every day what happens in countries where media freedoms are curtailed, where journalists are arrested or threatened for doing their jobs, where there is no such thing as a free press. We were founded to ensure that there would always be a platform to publish the stories of those people who cannot be heard in their own countries – media freedom is therefore one of the core principles which Index defends every day.

In my opinion the way in which journalists are treated is a health-check on the state of a government’s commitment to human rights. On whether they are upholding the democratic values that we all hold so dear. Whether that’s at a local or national level.

In the last decade the importance of news coverage has been made clear every day. In the UK, since 2014, we have had two referendums, three general elections, five Prime Ministers, a pandemic and a recession. We have never needed engaged journalists more – nor politicians to be accessible. Historically this was never an issue, politicians tend to like featuring in the media (and I say that as someone who was elected) and journalists are usually happy to oblige. A mainstay of British political engagement is the traditional morning media round – designed to set the news agenda for the day. Every day Government Ministers speak on the morning TV and radio news programmes – not just to announce new initiatives but to respond to the news of the day. I don’t doubt for a second that this is challenging and at times pretty uncomfortable for the politicians – but it is how we daily ensure that our politicians are accountable to their constituents.

However in recent days the British government has changed tack. The new Prime MInister, the Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP, has decreed that the morning media round will no longer be a daily occurrence. Ministers will not appear on news outlets unless they have something to announce, or if there is something the government wants to discuss. Journalists will struggle to speak truth to power if the power isn’t showing up. This is not the action of a government that is prepared to be held to account on the issues that matter to the people they seek to represent.

Where countries claim a democratic tradition, each has a cultural difference. They have a different feel and a different tradition. It is difficult to judge one against another. Journalists adhere to both their career and cultural norms and for some that may not be a daily interrogation of their government, but in the UK it has been for as long as I can remember. This is a bad decision by the new PM, a decision that I think he will regret and one that will be quietly dropped. We all deserve to know what our government is doing and in the UK – we are dependent on our journalists to find out. This is why we defend journalists both at home and abroad, because media freedom is a core tenet of our democracy.

There is no substitute for witnessing events firsthand and telling your readers about them. Reporting is simple like this. When asked by a contact if I wanted to cover a Just Stop Oil protest in West London this August I set my alarm.

JSO’s progenitor Insulate Britain inflicted misery on ordinary Londoners (our readers) in a month of direct action in September 2021. They blocked traffic by sitting down at junctions around the M25 to protest new fossil fuels. By 2022, it was blindingly obvious this invite was a chance to get up close to a protest group which had proved divisive across the country. Some think these more radical actions are justified while others worry they repel popular support for climate change activism.

Really it doesn’t matter what anyone thinks about Just Stop Oil’s tactics or the UK Government’s response to climate change, my job is to report who, what, where, when and why things are happening on my patch and let our readers decide. I can’t do this properly by relying on press officers.

At 6:30am on 26 August I arrived at Talgarth Road BP garage in Hammersmith with my laptop, portable charger, a pocket full of pens and a notebook.

I was late. Armed with special hammers used to break glass in an emergency, the protesters were already battering the pumps and spraying them with paint. I grabbed my phone, filmed it, and then sent it to our newsroom. They published it and started a live blog. I then began interviewing protesters, some of whom were already handcuffed, to ask why they were doing this. I planned to speak to the drivers and garage staff too.

I’m 24 and I’ve only been reporting for a year, but I’ve spent some time with the Metropolitan Police. I’ve joined the force for a ride along to see what frontline policing looks like and I’ve had polite exchanges at crime scenes. I’ve also had a couple of disagreements. I’d had one tiff about photographing a building which had exploded in East London earlier that month. It ended with me reading the College of Policing Guidelines on media relations to the officer from my phone. I was also once told I couldn’t take photos of a car that was parked outside a murder scene. After some back and forth, the officer wrapped the car in tape. I’m still not sure what this achieved.

Maybe it was these experiences, or my inexperience, but I wasn’t that surprised when – doing my job – I was singled out and detained, then arrested. I’ve been reliably informed since this isn’t normal.

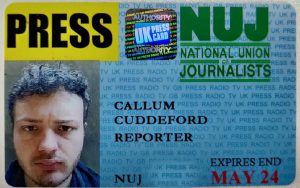

Callum Cuddeford’s press card did not stop his arrest

Hands cuffed at the front, pen in mouth, I asked the officer to look at my press card which he let me produce from my pocket. This didn’t make any difference.

The officers said I was accused of criminal damage by staff at the garage (a case of mistaken identity), and that they had to arrest me. My first thought was to shout at a nearby freelance photographer to make sure he got a good photo. I also tried to tell him to get a message to my editor. The officers shouted me down and said anything I said now could incriminate me. This was chilling, so I stayed quiet.

Clearly a press card is not a ‘Get out of Jail Free’ card. Just ask photographer Peter Macdiarmid (arrested by Surrey Police at a JSO protest 24 August), documentary maker Richard Felgate (arrested twice covering JSO protests), photographer Jamie Lashmar (stop and searched at JSO protest 19 October), photographer Tom Bowles (arrested and house searched by Herts Police at JSO protest 7 November) and LBC reporter Charlotte Lynch (arrested by Herts Police at JSO protest 8 November).

Though the arrests were made at different times, by different police forces, for different reasons, they all ended without a charge. Even if it is stupidity, mistaken identity or human error, it’s unsettling for freedom of expression and a waste of time for stretched emergency services.

I understand some officers are wondering why reporters and photographers know where the protests are happening, often before the police. The answer: Some get tip offs and others guess, but that doesn’t make us complicit. Suggesting so sets a dangerous precedent.

In all I was locked up for seven hours, which was uncomfortable, inconvenient and quite boring. But it was informative to feel helpless. I had the privilege of experiencing a police cell knowing I would probably be freed.

Still, the combination of a barren room, blasting light and constant thought-tennis led me into a moment of spiral. I questioned my own innocence.

The Police, Crime Sentencing and Courts Bill – opposed by senior police officers and three former Prime Ministers – was given royal assent in April. Human Rights group Liberty described the bill as “seriously worrying” and warned it will “hit those communities already affected by over-policing hardest”.

The new laws were designed to help police crackdown on disruption caused by Just Stop Oil, Insulate Britain and Extinction Rebellion, but on the face of it the new powers seems to have emboldened some police officers. Even if the police can produce a valid argument for each arrest, the result is still disturbing.

The alleged assault of a Daily Mirror reporter in Bristol in January 2021 and the arrest of a photographer at a demonstration in Kent in the same year shows over-policing isn’t new, but the consistency with which arrests have been made over the past few months feels like the natural result of a government shifting towards authoritarianism.

Police officers are under pressure in dangerous situations, but rights to film and photograph, report on civil disobedience and protect confidential sources are all fundamental to press freedom.

I can’t help but be sceptical about my arrest, especially in the context of this week’s triple nicking, but I still gave the officers the benefit of the doubt in a fast moving and potentially dangerous situation. Equally I can’t ignore the uncomfortable pattern emerging in which journalists should prepare themselves for a day in the cells if they want to cover a climate protest.

My release was expedited because I had a luminous yellow cycling bag on my back. When the police did finally check the CCTV (seven hours later) it was clear I wasn’t involved in the protest. I laughed about this with an officer as he handed me my things back, but it’s not a good solution.

Newsrooms and police forces need each other from crime scene to courtroom, witness appeals, giving victims of crime exposure, holding the police to account or indeed cracking down on illegal newsgathering.

You can bet it won’t put off a single reporter, but these arrests have already brought UK press freedom into question