18 May 2016 | Bosnia, Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News and features, Russia, Turkey, United Kingdom

Each week, Index on Censorship’s Mapping Media Freedom project verifies threats, violations and limitations faced by the media throughout the European Union and neighbouring countries. Here are five recent reports that give us cause for concern.

The Russian state media regulator Roskomnadzor began blocking Krym Realii, the Сrimean edition of Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty on Saturday 14 May.

A representative of Roskomnadzor confirmed that the regulator had blocked a page, which contains an interview with a leader of the Tatar Mejlis, at the request of the general prosecutor office. “Currently, Roskomnadzor is implementing measures for blocking and closing this website,” criminal prosecutor Natalia Poklonskaya told Interfax.

Krym Realii was established following the annexation of Crimea to Russia. Materials on the site are published in Russian, Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar languages.

Several editors at RBC media holding lost their jobs on 13 May following a meeting between top management with journalists. They include RBC editor-in-chief Elizaveta Osetinskaya, editor-in-chief of the RBC business newspaper Maksim Solyus, and RBC deputy chief editor Roman Badanin.

In a press release, RBC underlined that the dismissals were finalised as a mutual agreement of both parties, but sources from TV-Dozhd and Reuters claim managers have bowed to political pressure from the Kremlin.

The pressure against RBC began following investigations that have reportedly “irked the Kremlin“, including one on the assets of Vladimir Putin’s alleged daughter, Ekaterina Tikhonova.

Petar Panjkota, a journalist for the Croatian commercial national broadcaster RTL, was physically assaulted after he had finished a segment from the Bosnian town Banja Luka on 14 May.

Panjkota was reporting on parallel rallies in Banja Luka, the administrative centre of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated of Republika Srpska. He was reporting on protests organised by the ruling and opposition parties of the Bosnian Serbs. When he went off air, Panjkota was punched in the head by an unidentified individual, leaving bruises.

RTL strongly condemned the attack, calling it another attack on media freedom. No information has surfaced on the identity of the assailant.

On 12 May, the long-awaited white paper on the future of the BBC was unveiled. The BBC Trust is to be abolished and replaced by a new governing board including ministerial appointees. The board will be comprised of 12 to 14 members: the chair, deputy chair and members for each of the four nations of the UK will be appointed by the government and the remaining seats will be appointed by the BBC.

“It is vital that this appointments process is clear, transparent and free from government interference to ensure that the body governing the BBC does not become simply a mouthpiece for the government,” Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of Index on Censorship, said.

“Independence from government is essential for the BBC and these proposals don’t quite offer that,” Richard Sambrook, director of the Centre for Journalism at Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies and former BBC journalist, told Index on Censorship. “There is no reason the board can’t be appointed by an arms length, independent panel. Currently the plans are too close to a state broadcasting model.”

Two reporters working for Dicle News Agency (DİHA) reporters were detained in the eastern city of Van on 12 May. Nedim Türfent and Şermin Soydan were allegedly detained within the scope of an on-going investigation and taken to the anti-terror branch in the central Edremit district of Van.

Both were detained separately. According to Bestanews website, Nedim Türfent was detained when his car was stopped by state forces at the entrance of Van. Şermin Soydan was detained on her way to cover news in the city of Van.

7 Jan 2016 | France, Mapping Media Freedom, News and features, Statements, United Kingdom

When I started working at Index on Censorship, some friends (including some journalists) asked why an organisation defending free expression was needed in the 21st century. “We’ve won the battle,” was a phrase I heard often. “We have free speech.”

There was another group who recognised that there are many places in the world where speech is curbed (North Korea was mentioned a lot), but most refused to accept that any threat existed in modern, liberal democracies.

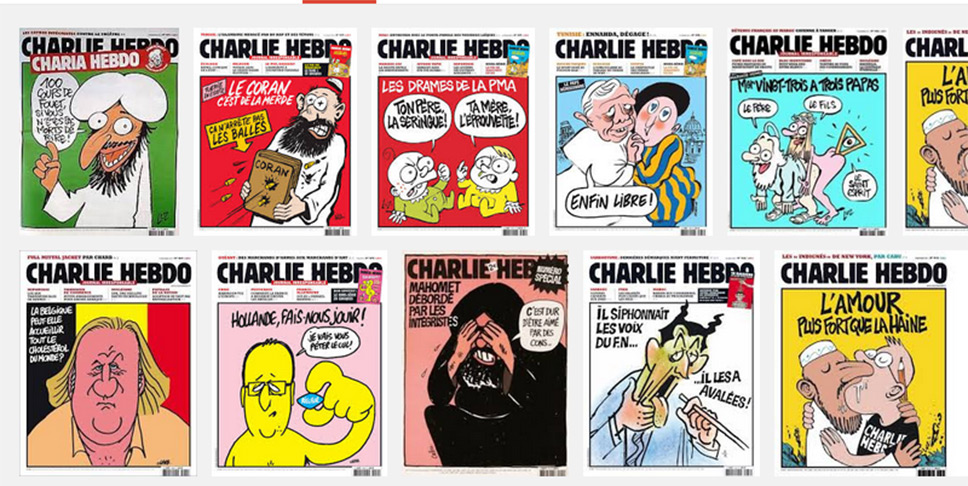

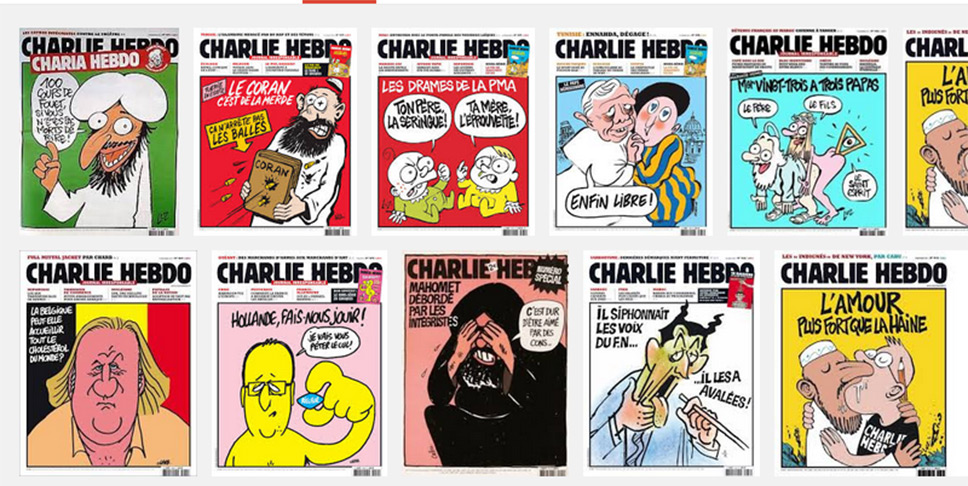

After the killing of 12 people at the offices of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, that argument died away. The threats that Index sees every day – in Bangladesh, in Iran, in Mexico, the threats to poets, playwrights, singers, journalists and artists – had come to Paris. And so, by extension, to all of us.

Those to whom I had struggled to explain the creeping forms of censorship that are increasingly restraining our freedom to express ourselves – a freedom which for me forms the bedrock of all other liberties and which is essential for a tolerant, progressive society – found their voice. Suddenly, everyone was “Charlie”, declaring their support for a value whose worth they had, in the preceding months, seemingly barely understood, and certainly saw no reason to defend.

The heartfelt response to the brutal murders at Charlie Hebdo was strong and felt like it came from a united voice. If one good thing could come out of such killings, I thought, it would be that people would start to take more seriously what it means to believe that everyone should have the right to speak freely. Perhaps more attention would fall on those whose speech is being curbed on a daily basis elsewhere in the world: the murders of atheist bloggers in Bangladesh, the detention of journalists in Azerbaijan, the crackdown on media in Turkey. Perhaps this new-found interest in free expression – and its value – would also help to reignite debate in the UK, France and other democracies about the growing curbs on free speech: the banning of speakers on university campuses, the laws being drafted that are meant to stop terrorism but which can catch anyone with whom the government disagrees, the individuals jailed for making jokes.

And, in a way, this did happen. At least, free expression was “in vogue” for much of 2015. University debating societies wanted to discuss its limits, plays were written about censorship and the arts, funds raised to keep Charlie Hebdo going in defiance against those who would use the “assassin’s veto” to stop them. It was also a tense year. Events discussing hate speech or cartooning for which six months previously we might have struggled to get an audience were now being held to full houses. But they were also marked by the presence of police, security guards and patrol cars. I attended one seminar at which a participant was accompanied at all times by two bodyguards. Newspapers and magazines across London conducted security reviews.

But after the dust settled, after the initial rush of apparent solidarity, it became clear that very few people were actually for free speech in the way we understand it at Index. The “buts” crept quickly in – no one would condone violence to deal with troublesome speech, but many were ready to defend a raft of curbs on speech deemed to be offensive, or found they could only defend certain kinds of speech. The PEN American Center, which defends the freedom to write and read, discovered this in May when it awarded Charlie Hebdo a courage award and a number of novelists withdrew from the gala ceremony. Many said they felt uncomfortable giving an award to a publication that drew crude caricatures and mocked religion.

Index’s project Mapping Media Freedom recorded 745 violations against media freedom across Europe in 2015.

The problem with the reaction of the PEN novelists is that it sends the same message as that used by the violent fundamentalists: that only some kinds of speech are worth defending. But if free speech is to mean anything at all, then we must extend the same privileges to speech we dislike as to that of which we approve. We cannot qualify this freedom with caveats about the quality of the art, or the acceptability of the views. Because once you start down that route, all speech is fair game for censorship – including your own.

As Neil Gaiman, the writer who stepped in to host one of the tables at the ceremony after others pulled out, once said: “…if you don’t stand up for the stuff you don’t like, when they come for the stuff you do like, you’ve already lost.”

Index believes that speech and expression should be curbed only when it incites violence. Defending this position is not easy. It means you find yourself having to defend the speech rights of religious bigots, racists, misogynists and a whole panoply of people with unpalatable views. But if we don’t do that, why should the rights of those who speak out against such people be defended?

In 2016, if we are to defend free expression we need to do a few things. Firstly, we need to stop banning stuff. Sometimes when I look around at the barrage of calls for various people to be silenced (Donald Trump, Germaine Greer, Maryam Namazie) I feel like I’m in that scene from the film Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels where a bunch of gangsters keep firing at each other by accident and one finally shouts: “Could everyone stop getting shot?” Instead of demanding that people be prevented from speaking on campus, debate them, argue back, expose the holes in their rhetoric and the flaws in their logic.

Secondly, we need to give people the tools for that fight. If you believe as I do that the free flow of ideas and opinions – as opposed to banning things – is ultimately what builds a more tolerant society, then everyone needs to be able to express themselves. One of the arguments used often in the wake of Charlie Hebdo to potentially excuse, or at least explain, what the gunmen did is that the Muslim community in France lacks a voice in mainstream media. Into this vacuum, poisonous and misrepresentative ideas that perpetuate stereotypes and exacerbate hatreds can flourish. The person with the microphone, the pen or the printing press has power over those without.

It is important not to dismiss these arguments but it is vital that the response is not to censor the speaker, the writer or the publisher. Ideas are not challenged by hiding them away and minds not changed by silence. Efforts that encourage diversity in media coverage, representation and decision-making are a good place to start.

Finally, as the reaction to the killings in Paris in November showed, solidarity makes a difference: we need to stand up to the bullies together. When Index called for republication of Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons shortly after the attacks, we wanted to show that publishers and free expression groups were united not by a political philosophy, but by an unwillingness to be cowed by bullies. Fear isolates the brave – and it makes the courageous targets for attack. We saw this clearly in the days after Charlie Hebdo when British newspapers and broadcasters shied away from publishing any of the cartoons featuring the Prophet Mohammed. We need to act together in speaking out against those who would use violence to silence us.

As we see this week, threats against freedom of expression in Europe come in all shapes and sizes. The Polish government’s plans to appoint the heads of public broadcasters has drawn complaints to the Council of Europe from journalism bodies, including Index, who argue that the changes would be “wholly unacceptable in a genuine democracy”.

In the UK, plans are afoot to curb speech in the name of protecting us from terror but which are likely to have far-reaching repercussions for all. Index, along with colleagues at English PEN, the National Secular Society and the Christian Institute will be working to ensure that doesn’t happen. This year, as every year, defending free speech will begin at home.

9 Dec 2015 | Campaigns, mobile, Statements

Index on Censorship opposes the proposal to ban Donald Trump from entering the UK.

“Donald Trump should not be banned from entering the UK. The best way to tackle views with which you disagree, including bigoted ones, is to allow discussion about them to take place so they can be openly countered. If you feel people’s arguments are hateful then the best way to expose that is in debate. Banning people just adds to their status and often increases their profile, and makes the arguments more popular. It does nothing to eradicate those views,” Index CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

24 Sep 2015 | mobile, News and features, United Kingdom

Photograph: Marcos Mesa Sam Wordley

The shock general election result in May gave David Cameron licence to lay out his vision for Britain in the first Conservative Queen’s Speech for almost 20 years. Gone were the concessions to the Liberal Democrats of five years previous, and instead the key planks of the Conservative manifesto were there in full. Expected measures to cut the deficit, reform welfare and introduce an in/out EU referendum were all announced. But, according to many, another common thread ran through the new government’s legislative programme: an assault on free speech.

“We’re deeply concerned that the government says one thing – that it believes freedom of expression is a fundamental British value – but in practice doesn’t believe that and is introducing legislation that could have quite a severe impact on freedom of expression,” says Jodie Ginsberg, chief executive of Index on Censorship, which campaigns against attacks on free speech across the globe.

Critics of the Conservatives’ record on civil liberties point to the resurrection of plans that were sidelined during the last Parliament, largely because of Lib Dem intervention. Privacy activists are alarmed that the new Investigatory Powers Bill may represent the revival of the so-called snoopers charter, allowing the security services access to everyone’s online and social media records. Plans to abolish the Human Rights Act and replace it with a British Bill of Rights have been delayed.

But proposals that have free speech campaigners up in arms are being introduced over the coming months. The Extremism Bill will introduce new banning and extremism disruption orders, giving the home secretary and other agencies the power to intervene against suspected extremist groups, and strengthen Ofcom’s role in tackling broadcasters who transmit extremist content.

Introducing it in May, the Prime Minister said: “For too long, we have been a passively tolerant society, saying to our citizens: as long as you obey the law, we will leave you alone.”

The bill is part of the government’s five-year counter-extremism strategy to combat Islamist extremism and the increasing number of Britons travelling abroad to fight for Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (Isis). A key component of this strategy will be challenging those who promote “non-violent extremism”, said David Cameron in a wide-ranging July speech.

He said: “This means confronting groups and organisations that may not advocate violence – but which do promote other parts of the extremist narrative.

“We’ve got to show that if you say ‘yes, I condemn terror, but the kuffar are inferior’, or ‘violence in London isn’t justified, but suicide bombs in Israel are a different matter’ then you too are part of the problem.” He added that simply condemning Isis atrocities was insufficient, and that “we must demand that people also condemn the wild conspiracy theories, the anti-Semitism, and the sectarianism too”.

A lack of clarity on how the government will define what constitutes non-violent extremism has caused alarm among many in the Muslim community. Dr Shuja Shafi, secretary general of the Muslim Council of Britain, said there was concern that the strategy would “set new litmus tests which may brand us all as extremists, even though we uphold and celebrate the rule of law, democracy and rights for all”.

“The Prime Minister hasn’t given concrete proposals. The home secretary was asked to define extremism and she wasn’t able to do that,” says Mohammed Shafiq, chief executive of the Ramadhan Foundation, a Muslim welfare organisation.

Shafiq questioned which views would be considered beyond the pale. “If, for example, you say you believe in sharia law the Prime Minister is suggesting that will make you an extremist and you could potentially face infringement of your civil liberties by expressing those views. It could be a Muslim who says he opposes gay marriage. Does that make him a bigot? I think it’s a really dangerous erosion of civil liberties.

“My approach is very simple – if you believe in freedom of speech as I do, then the likes of Anjem Choudary, Tommy Robinson and other far-right leaders have the right to express their views, and equally we have the right to challenge, debate and expose them.

“But you don’t defeat extremism by taking away an individual’s ability to put their view across.”

In the speech, Cameron said the ideology that underpins Islamist extremism must be countered by “British values”, such as democracy and the rule of law.

But Ginsberg agrees that having such broad definitions of “acceptable” speech means that it is impossible to know what could be deemed extremist. “[Cameron] has talked very vaguely about British values but does that mean that anyone who questions the current voting system, for example, or the current political set up is being un-British? Or says that they favour anarchy even if they’re not actively advocating violence. Is that unacceptable?

“What’s fundamental about democracy is that you should be able to ask questions and to express views that sometimes will conflict with the prevailing political thinking.”

Other upcoming legislation is also causing alarm to free speech campaigners. The Trade Union Bill has been described as the most radical package of union reforms since the 1980s and dramatically alters how industrial action is called for and carried out. The bill would introduce a turnout threshold of 50 per cent on strike ballots, a 14-day notice period on strikes, allows employers to bring in agency workers to replace striking staff and outlines new regulations on picketing to prevent “intimidation” of non-strikers. It has been bitterly opposed by unions and the Labour Party.

But one small line in an accompanying consultation document to the bill has drawn particular gasps of astonishment. It proposes that unions must inform employers and police 14 days ahead of strike action of any online or social media activity it plans to adopt and whether a loudspeaker or banners will be used on the picket line. Failure to comply could result in an enforcement order being served or a fine. “It would mean there are enormous levels of employer and political scrutiny of trade union protests, beyond what we think is the norm among modern democracies in the developed world.

The worry is that the package of measures in the bill taken together substantially undermine the basic democratic right to strike,” says Nicola Smith, head of economic and social affairs at the TUC.

Although ministers say that restrictions would not apply to individuals, labour groups say that employees who already have little legal protection will feel intimidated and less likely to publicly support strike action. Many also believe it would be unworkable.

“It will be impossible to police. Who can control Facebook or Twitter? Who will monitor that?” says Carolyn Jones, director of the Institute of Employment Rights, a labour movement thinktank. “If one stray person – who may not be in the union – if they send something out, does that mean the strike is then illegal? And then the union has got to run the very expensive, very-time consuming ballots because this is seen to be illegitimate.

“The threat is there – it’s intimidation. What happened to freedom of association? There are so many bits of international law that it would threaten to break. It’s madness – is it proportionate to the problem? No.”

Union concerns are shared by free speech campaigners. “It’s an attack on freedom of expression, it’s a potential attack on freedom of assembly… The idea that you might have to seek permission from government or that government might be vetting the kinds of people who can and can’t say things is extremely worrying,” says Ginsberg.

But the government defended the bill as a whole. A Department for Business, Innovation & Skills spokesperson says: “People have the right to know that the services on which they and their families rely will not be disrupted at short notice by strikes supported by a small proportion of union members.

“The ability to strike is important but it is only fair that there should be a balance between the interests of union members and the needs of people who depend on their services.”

Index on Censorship is to launch a campaign against the Extremism Bill, and unions are resisting the changes to strike laws. But campaigners are gloomy about the prospect of the government changing tack over the long-term and abandoning policies they believe infringe on free speech. “This has been the direction of travel for a long time,” says Ginsberg, particularly in relation to national security. “The problem is that there is only one direction that it’s going in and that’s to restrict further free expression. We’re not seeing any move back or any relaxation of the foot on the pedal.”

This article originally appeared on 23 September 2015 at Big Issue North.