23 Jan 2015 | News

Bahrain

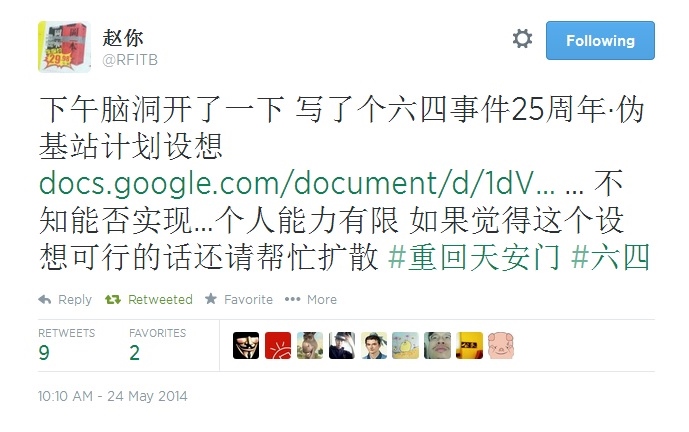

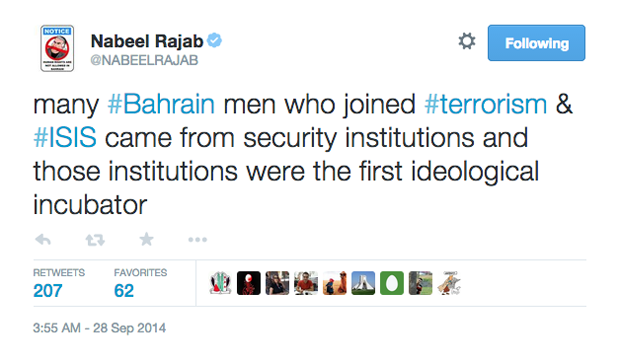

This week, prominent Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab was handed down a six month suspended sentence over a tweet in which both the country’s ministry of interior and ministry of defence allege that he “denigrated government institutions”. Rajab was only released last May after two years in prison, over charges that included sending offensive tweets. His experience is not unique in Bahrain. In May 2013, five men were arrested for “insulting the king” via Twitter.

Turkey

A former Miss Turkey was recently arrested for sharing a satirical poem criticising the country’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on her Instagram account. She is set to go on trial later this year. Turkey has a chequered relationship with social media, temporarily banning both Twitter and YouTube in the wake of the Gezi Park protests, in large part organised and reported through social media. In 2013, authorities arrested 25 individuals for spreading “untrue information” on social media.

Saudi Arabia

(Photo: Gulf Centre for Human Rights)

In late 2014, women’s rights activist Souad Al-Shammari was arrested during an interrogation over some of her tweets. The charges against her include “calling upon society to disobey by describing society as masculine” and “using sarcasm while mentioning religious texts and religious scholars”, according to the Gulf Centre for Human Rights.

France

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)

(Photo: Réseau Voltaire [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons)

Following the series of terrorist attacks in Paris in early January, at least 54 people have been detained by police for “defending or glorifying terrorism”. A number of the cases, including against comedian Dieudonne M’bala M’bala, are believe to be connected to social media comments.

Britain

A 22 year old man was arrested in for “malicious communication” following Facebook messages made in response to the murder of soldier Lee Rigby, and another user was arrested after taunting Olympic diver Tom Daly about his dead father. More recently, police arrested a 19-year-old man over an “offensive” tweet about a bin lorry crash in Glasgow that killed six people. TV personality Katie Hopkins, known for her controversial tweets, was also reported to Scottish police following some tasteless tweets about about Scots. The incident prompted Scottish police the to post their now infamous tweet declaring they would continue to “monitor comments on social media“.

China

Online activist Cheng Jianping was arrested on her wedding day in 2010 for “disturbing social order” by retweeting a joke by her fiance. She was sentenced to one year of “re-education through labour”. Twitter is officially banned in China, and microblogging site Weibo is a popular alternative. In 2013, four Weibo users were arrested for spreading rumours about a deceased soldier labelled a hero and used in propaganda posters. The four were said to have “incited dissatisfaction with the government”, according to the BBC.

Australia

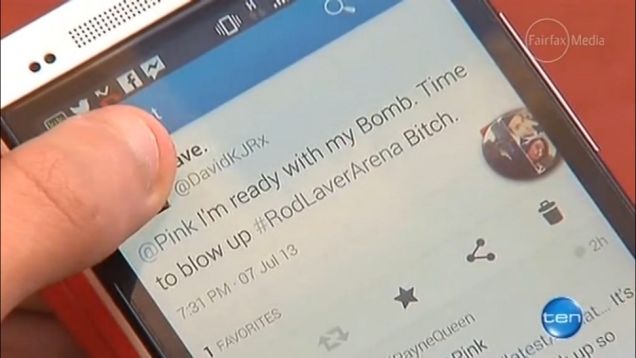

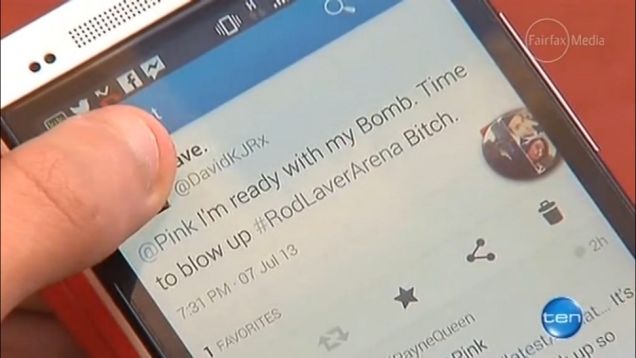

A teen was arrested prior to attending a Pink concert in Melbourne for tweeting: “I’m ready with my Bomb. Time to blow up #RodLaverArena. Bitch.” The tweet referenced lyrics from the American popstar’s song Timebomb.

India

An Indian medical student was arrested in 2012 over a Facebook post questioning why her city of Mumbai should come to a standstill to mark the death of a prominent politician. Her friend was arrested for liking the post. Both were charged with engaging in speech that was offensive and hateful.

United States

Back in 2009, a New York man was arrested, had his home searched and was placed under £19,000 bail for tweeting police movements to help G20 protesters in Pittsburgh avoid the officers. According to Global Voices, it is unclear whether his actions were actually illegal at the time.

Guatemala

A man was arrested in 2009 for causing “financial panic” by tweeting that Guatemalans should fight corruption by withdrawing all their money from banks.

This article was posted on 23 January, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

19 Jan 2015 | Events

Presenting the world premiere of a collection of 12 explosive political five minute plays by writers including Mark Ravenhill, Neil LaBute and Caryl Churchill.

Arising from events and decisions relating to The Underbelly and Incubator Theatre’s The City, Exhibit B and the Barbican, and The Tricycle Theatre.

Each performance will include all twelve five minute plays and a lively post-show discussion exploring freedom of expression in UK arts today. Engage in discussion with the commissioned writers and a range of free expression advocates .

The post-show debate on on Friday 30th January will feature Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg.

WHERE: Theatre Delicatessen, London, EC1R 3ER

WHEN: Monday 26th – Saturday 31st January, 7:30pm & Sat Matinee

TICKETS: £15 / £12 – available here

This event is produced by Offstage Theatre, in association with Theatre Uncut, and supported by Index on Censorship and Free Word.

19 Jan 2015 | Iraq, News, United Kingdom

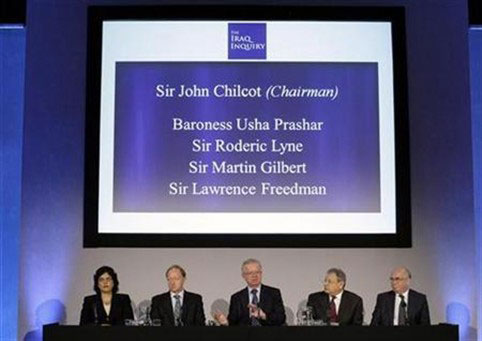

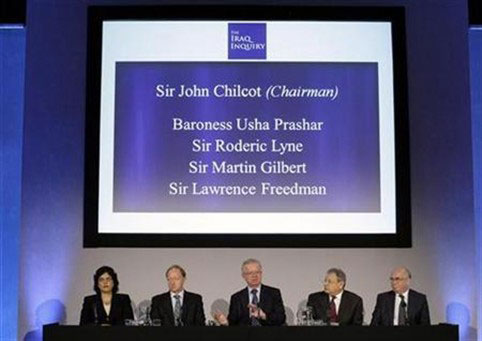

Despite his repeated assertions that it is nothing to do with him, it is now clear that British Prime Minister David Cameron not only has the power to hold back the long-awaited Chilcot Inquiry into the UK’s involvement in the Iraq war until after the election – but may actually do so. The prime minister who championed free speech but wants to duck out of TV election debates seems prepared to suppress the report of the Iraq inquiry on an equally flimsy pretext. If he does he will again find himself on the wrong side of the argument, perhaps with only opposition leader Ed Miliband for company.

The inquiry has been in the headlines a lot lately, with politicians calling for the report to be published before the election and speculative stories about whether this is or isn’t possible. Having significantly compromised to extricate itself from a long-running dispute over which documents it can disclose in support of its findings, the inquiry, launched in 2009, is now undertaking the “Maxwellisation” process of notifying people that it intends to criticise and inviting their responses.

But publication before the election in May will depend not only on when Sir John Chilcot delivers the report to Cameron but what cut-off date is applied. Two weeks ago Cabinet Office minister Lord Wallace re-iterated that the government will hold back the report if it is not completed by the end of February. This is a month before parliament is dissolved on 30 March and pre-election “purdah” officially begins. Wallace justified this early deadline on the grounds that:

part of the previous Government’s commitment was that there would be time allowed for substantial consultation on and debate of this enormous report when it is published.

There was, in fact, no promise of “substantial consultation” from the previous government. It appears to have been invented to lengthen the process and justify interfering with an inquiry whose independence Cameron has repeatedly emphasized. Last month he said: “I am not in control of when this report is published. It is an independent report, it is very important in our system that these sort of reports are not controlled or timed by the government.”

A day after Wallace’s statement, Cameron repeated the error at Prime Minister’s Questions: “…it is up to Sir John Chilcot when he publishes his report. He will make the decision, not me.

A further day later Number 10 issued a “clarification”. According to the Telegraph, the prime minister’s deputy official spokesman said that in fact Cameron would have the final say on the timing the publication once has received the report. She said: “The point the Prime Minister has made is the timing of the report and its completion is a matter for the inquiry. “In terms of publication, the government would seek to publish it as swiftly as possible while ensuring parliament had the right time and opportunity to debate and look at it.”

This looks very much as if Cameron is prepared to suppress the report on the same grounds as Wallace gave – that MPs need a lot of time to study it. But Downing Street clearly knows that if Cameron expressly signed up to the February deadline he would completely contradict his own promise not to control the timing of the report. When I asked one of Cameron’s spokespeople whether he agrees with the deadline, he returned to the pre-clarification position of denial: “as the PM has said in the House of Commons, it is up to the Inquiry, not him”.

Meanwhile Labour leader Ed Miliband has kept very quiet on the issue and, having spoken to Labour’s media people, it is clear that they don’t want to talk about it either.But neither leader can fudge the issue much longer as a cross-party coalition of MPs, including Plaid Cymru, pushes for publication and challenges the government’s deadline. They have now secured a half day parliamentary debate on 29 January. The Lib Dems have challenged the government to publish the report within a week of receiving it, even during the election campaign. Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon called for politicians to unite on the issue, prompting Scottish Labour’s leader Jim Murphy to demand “the earliest possible publication”. Whether that is a rejection of the February deadline is unclear.

Looking further ahead, it seems unlikely that Cameron would really have the nerve to sit on the report, for as long as two months before the election. Even if you accept the official position that it needs to be put before parliament and cannot therefore be published during the election campaign, could he realistically refuse to publish it while parliament is sitting? With MPs treading water during March, to claim that there is not time to debate it would be entirely untenable.

We should never expect too much from an establishment inquiry, particularly without the key evidence. But the government’s argument for stalling the report is effectively that the desire of the political class for the perfect time and space to discuss it trumps voters’ right to be informed. After the massive loss in public trust that the Iraq war caused, surely Cameron wouldn’t dare.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

This article was posted on January 19, 2015 at indexoncensorship.org.

15 Jan 2015 | Bahrain, News, Statements

Nabeel Rajab during a protest in London in September (Photo: Milana Knezevic)

Index on Censorship is calling on the government of Bahrain to drop its charges against human rights campaigner Nabeel Rajab.

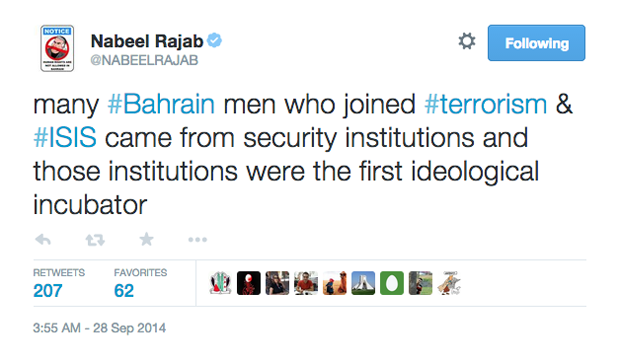

In October a Bahraini court ruled that Nabeel Rajab would face criminal charges stemming from a single tweet in which both the ministry of interior and the ministry of defence allege that he “denigrated government institutions”. If convicted, Rajab could face up to six years in prison.

“Nabeel Rajab, an Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression award winner, was arrested for a tweet in which he did no more than simply express an opinion. For this he faces years in jail. As the world renews its focus on freedom of expression it is vital that we defend those punished for speaking out no matter where they are in the world. Join us in calling for Nabeel’s release,” Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

15 January 2015 — 16 human rights organisations have written to 47 States to express grave concern ahead of a 20 January verdict in the trial of Nabeel Rajab, a prominent Bahraini human rights defender. Additionally, Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain, The Bahrain Center for Human Rights and The Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy sent letters to members of parliament in all 47 States and United Nations officials, urging them to publicly call on the Government of Bahrain to drop all charges against Rajab.

On 1 October 2014, Rajab reported to the Cyber Crimes Unit of Bahrain’s General Directorate of Criminal Investigations (CID) after being summoned for questioning. Following hours of interrogation in relation to a tweet he published while abroad, Rajab was arrested. The tweet read: “Many #Bahrain men who joined #terrorism & #ISIS came from security institutions and those institutions were the first ideological incubator.”

For this tweet, Rajab was charged with insulting the Ministries of Interior and Defense under article 216 of Bahrain’s penal code, which states that “A person shall be liable for imprisonment or payment of a fine if he offends by any method of expression the National Assembly, or other constitutional institutions, the army, law courts, authorities or government agencies.” Rajab was released on bail on 2 November, but was banned from traveling outside the country. If found guilty, he could face up to six years in prison.

The charges leveled against Rajab are illegal under Bahrain’s commitments to the international community and international human rights law. Bahrain is party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), having acceded to the covenant in 2006. Article 19 of the ICCPR provides everyone with the fundamental rights to opinion and expression. Further, international jus cogens norms protect against the arbitrary deprivation of liberty, especially in relation to acts related to free expression. By prosecuting Rajab for statements that he made over Twitter, the Bahraini government violates its own commitments to the international community.

The ongoing suppression of basic human rights in Bahrain has drawn heavy criticism from the international community. In June 2014, 47 United Nations Member States signed a joint statement on Bahrain expressing concern “about the continued harassment and imprisonment of persons exercising their rights to freedom of opinion and expression, including human rights defenders.” The statement also called on Bahrain to “release all persons imprisoned solely for exercising human rights, including human rights defenders.” In 2014 a European Parliament resolution also called for “the immediate and unconditional release of all prisoners of conscience, political activists, journalists, human rights defenders and peaceful protesters, including Nabeel Rajab. …”

The undersigned NGOs close the letter by urging the international community to explicitly and publicly call for the Government of Bahrain to immediately drop all charges against Rajab and the many others currently facing charges or serving arbitrary jail sentences for exercising their rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly.

NGO signatories:

Amnesty International

CIVICUS

English Pen (Letter to the UK Foreign Office only)

Freedom House

Front Line Defenders

Human Rights Watch

Index on Censorship

Pen International

Project on Middle East Democracy

Rafto Foundation for human rights (Letter to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs only)

FIDH in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

OMCT in the framework of the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders

Americans for Democracy and Human Rights in Bahrain

Bahrain Center for Human Rights

Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy

Gulf Center for Human Rights

Additional Background:

Nabeel Rajab is the President of the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, Deputy Secretary General of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), and a member of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East Advisory Board.

Bahraini authorities have previously prosecuted Rajab on politically motivated charges. They have never presented any credible evidence that Rajab has advocated, incited or engaged in violence.

Rajab was detained from May 5 to May 28, 2012, for Twitter remarks criticizing the Interior Ministry for failing to investigate attacks carried out by what Rajab said were pro-government gangs against Shia residents. On 28 June 2012, a criminal court fined him 300 Bahraini Dinars (US$790) in that case.

Authorities again detained Rajab on 6 June 2012, for another Twitter remark calling for Prime Minister Khalifa bin Salman al Khalifa to step down. On 9 July 2012, a criminal court convicted and sentenced him to three months in prison on that charge. A court of appeal overturned that verdict, but in a separate case a criminal court sentenced him to three years in prison for organizing and participating in three unauthorized demonstrations between January and March 2012. An appeals court reduced the sentence to two years, which Rajab completed in May 2014.

In September 2014, Rajab traveled to Europe to call for stronger international action on Bahrain. He met with representatives of various European governments and the EU, spoke to the media, and addressed UN fora.

In the current case, Rajab was detained on 1 October 2014, within 24 hours of his return to Bahrain.

![(Photo: « Source : Réseau Voltaire » [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.indexoncensorship.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Dieudonné_Axis_for_Peace_2005-11-18.jpg)