14 Apr 2014 | News, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

Asif Quraishi, better known as drag queen Asifa Lahore, sits unassumingly in a TV studio. “One question I’d like to ask”, he says, “is when will it be all right to be Muslim and gay?”

The programme is Twitter-powered BBC Three debate series Free Speech, whose host Rick Edwards (of Tool Academy and, unexpectedly, Cambridge) makes Nicky Campbell seem subdued, and where no thought is too complex for 140 characters. Producers, show name notwithstanding, spiked the question from a previous edition when officials at Birmingham Central Mosque, where Free Speech filmed on March 13, “expressed deep concerns” about gay Muslims being discussed. The speed at which showrunners acquiesced, postponing the segment, speaks to a wider trend.

The first guest to comment, kufi-clad Portuguese convert Abdullah al Andalusi, calls condemning gay sex “the Islamic position” with a party leader’s certainty. It’s unsurprising: al Andalusi, who defends public segregation by gender and from whose talks women have been banned, seeks a nondemocratic “modern [Islamic] Caliphate” under sharia government, free among other things of “women wearing bikinis”, “the hijab being optional” and “men and women having identical inheritance and gender roles”. Al Andalusi rails in-studio against notions of “extremism”, declaring them a means of profiling “Muslims with orthodox beliefs”. He sees himself as holding these, and so apparently do programme-makers, since he speaks much more than Asif does.

The counter-extremist whose work he attacks, Lib Dem candidate for Hampstead Maajid Nawaz, is also in the room. (“I will speak out”, he tells the drag performer, “on your right to identify however you want.”) Nawaz too has been hounded by religious would-be censors, despite being a Muslim himself. This January, following the LSE’s attempts to ban it, he tweeted an image from the atheist web strip Jesus and Mo, commenting “This is not offensive and I’m sure God is greater than to feel threatened by it.” A subsequent Change.org petition calling for his sacking gained over 20,000 signatures, some with death threats attached. Though Nick Clegg eventually stepped in to condemn them, spokespeople told the press the party “urged all candidates to be sensitive to cultural and religious feelings”, and Nawaz – presumably after internal bickering – conceded in a joint statement with Mohammed Shafiq, head of the Ramadhan Foundation and leader of the witchhunt, that “images of the spiritual leaders of all religions should be deemed to be respectful”.

In February Shazad Iqbal, a hitherto unknown British Muslim, used a similar petition to demand YouTube remove Katy Perry’s “Dark Horse” video, in which an Ancient Egyptian turns to sand whose pendant, on close inspection, reads “Allah”. “Blasphemy is clearly conveyed in the video”, Iqbal wrote. “Such acts are not condoned nor tolerated.” While the offending necklace, which had to be indicated using photoshopped freeze-frames, was barely visible, tens of thousands of signatures poured in – today, the page boasts more than 65,000 – and Perry’s producers digitally obscured it.

Iqbal, who used his petition site to share evangelistic videos, gained a platform much like Iqbal’s and al Andalusi’s. All three, and countless more religious rightists, have sold themselves as commentators, “community leaders” and de facto spokesmen for Muslims (“men” is applicable here), grabbing the spotlight neither through skilled writing nor through views polls say are actually widespread. They owe their standing to officialdom’s mounting anxiety to please the most censorious believers, its instinct that those eagerest to cleanse the public sphere of blasphemy are those who matter most.

Recycled lines about a scaremongering anti-Muslim press over-reporting extremism come easily, but demagogues of this kind are media’s darlings; far from casting them as bogeymen, it heaps meetings with politicians, TV appearances and public validation on them. Nor is this pattern unique to Islam. In a 2012 speech for the National Secular Society, Pragna Patel of Southall Black Sisters cites the case of Behzti, a play by Gurpreet Kaur Bhatti which portrayed sexual violence in a Sikh temple. “Fundamentalists, but also so-called moderates,” says Patel, “took offence, protested and had the play removed”, theatre staff bowing to their demands. Leaders on the Sikh right, she says, stated once Bhatti entered hiding that if Labour’s Racial and Religious Hatred Act had existed at the time, it would have been used to censor the play.

Authorities sided with those attacking her, as they sided with Shafiq over Nawaz, al Andalusi and Birmingham Central Mosque over Quraishi, Iqbal over every Muslim undisturbed by Katy Perry. Reformists and minorities like them, as much as a free society, are casualties of this love for religious censors. If minor faiths, still mysteries in the public eye, need representatives, far better ones exist: A media that paints puritans and fanatics as mainstream forfeits its right to condemn them.

This article was posted on 14 April 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

3 Apr 2014 | News, Politics and Society, United Kingdom

(Illustration: Shutterstock)

The idea, or perhaps ideal, of innocence plays a complex part in our society: We value it, but still have a very strong sense of its limited use. In a five-year old, innocence is a delight; in a 25-year old an annoyance; in a 45-year old? A tragedy.

This is no bad thing; central to our modern conception of children’s rights is the notion that they are blameless: An innocent child cannot be held responsible for, say, the actions of a sexual abuser. An innocent child does not have the faculty to enter into a contract to sell their labour: An innocent child cannot start a physical fight with a grown-up parent.

By the time we reach majority, we are supposed to be able to negotiate our way through the world. We probably retain some of that innocence well beyond the age of 18, but society has to draw a line somewhere.

There is a downside to this right and justified urge to uphold the immaculate status of the child; it comes in the form of the ever-returning moral panic.

This week, the Chief Inspector of Constabulary, Tom Winsor, in his assessment of the “state of policing” in England and Wales for 2012/2013, warned of the dangers of smartphones and their capability for warping young minds.

“Modern technology,” Winsor notes ”provides new and more effective ways for children to be abused, pursued and drawn into crime. Moreover, violence and sexually explicit material available to children on smartphones and other devices desensitise them and distort and confuse their perceptions of normal behaviour.”

The first part is most likely true, at least the “new” part, though I would be wary of the idea that new technologies are somehow more “effective” for child abusers. The majority of incidents of abuse are perpetrated by people already close to children, not strangers.

But the second assertion, on “desensitisation”, is as old as the hills, and fits into a pattern of moral panics that has been present for decades. Elsewhere, Winsor cites the many causes of crime, which include:

“social dysfunctionality, families in crisis, the failings of parents and communities, the disintegration of deference and respect for authority, the fears of teachers, alcohol, drugs, a misplaced and unjustified desire or determination to exert power over others, envy, greed, materialism and the corrosive effects of readily-available hard-core pornography and the suppression of instincts of revulsion to violence through the conditioning effect of exposure to distasteful and extreme computer games and films.”

This list introduces the great friend of the moral panic, declinism (a concept explored by Index on Censorship chair David Aaronovitch in a BBC documentary); British society has been in decline, roughly since the Suez crisis, or the time the first Teddy Boy swung his first bicycle chain in anger.

British young people are in danger of corruption, now more than ever; “now” being any given moment in the past 60 years. Bill Haley, Mick Jagger, David Bowie, Suzi Quatro, Space Invaders, “snuff movies”, Snoop Doggy Dogg, Chucky from Child’s Play, Mortal Kombat, Manhunt, Grand Theft Auto, “Skins parties”… all have presented a clear corrupting influence on young people.

And yet, civilisation has survived. In fact, as Martha Gill points out in the Daily Telegraph, today’s young folk are remarkably pure and well-behaved.

The country has not, in fact, gone to the dogs. More to the point, there was never an age of innocence, either for young people or for the nation.

In the years 1947/1948, which many on both the right and left might consider halcyon days for Britain, now-national-treasure Richard Attenborough played a teen killer in two consecutive films – Pinky in the adaptation of Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock, and Percy Moon in Dulcimer Street, the adaptation of Norman Collins’s London Belongs To Me.

Both are young men with wild ideas (though naive Percy cannot come anywhere near the badness and vindictiveness of Greene’s monstrous, tortured Pinky). To use Winsor’s language, both display, to varying degrees, those dread traits “materialism” and “a misplaced and unjustified desire or determination to exert power over others”. Their creators clearly find sympathy in them, but clearly are working from a template of a corrupted modern youngster. Notably, in Dulcimer Street, Percy is an avid reader of the new, American (read “alien to old England), detective and thriller comics.

The combination of declinism and moral panic reached its acme in spring of 1993, after two 10-year old boys took a two-year old toddler from a Bootle shopping centre to a railway sidings, where they tortured and killed him.

The murder of James Bulger by Jon Venables and Robert Thomson was as inexplicable as it was horrific. But proved, for those looking for the evidence, that British society had reached a devastating new low, Moral panic-ers soon found out why: The, silly, schlocky horror movie “Child’s Play 3” was the culprit. Apparently one of the boys’ parents had rented the film. That was it, in spite of their being scant evidence the boys had even seen the film. In fact, as Professor Stan Cohen noted in his updated version of Folk Devils and Moral Panics, “a senior Merseyside Police Inspector revealed that checks on the family homes and rental lists showed that neither Child’s Play nor anything like it had been viewed.”

The pattern has repeated since, most particularly in erroneous reports in 2004 that the videogame Manhunt had influenced a teenager who killed a friend, in spite of police insistence that the game had nothing to do with it.

Declinism is insidious in that it gives young people and their culture (pop music, games) a raw deal. Moral panics, while they should be resisted, are at least understandable. But to be genuine in our efforts to protect young people and their innocence, we should remain rational, rather than merely seeking out the latest scapegoat. More often than not, it turns out that the kids are all right after all.

This article was published on April 3, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

27 Mar 2014 | News, Politics and Society, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom, Young Writers / Artists Programme

There are people out there who claim they can make things go viral. They are lying.

They are the digital version of economists, confidently asserting they can predict the behaviour of millions of barely-rational people, when nothing of the sort is possible. You can maximise the chances of something going viral but you can’t guarantee it, let alone predict it.

In the last few months, I’ve written about a dying man being deported by the Home Office, the decision to secretly restart removals to Somalia and a Home Office document which admits they have no idea whether their drug policy is working. They do fine, but you can often watch stories you spent time working on go out to the usual liberal minded folk, whirl around for a bit and then die a respectable death, with little to no impact on the wider world.

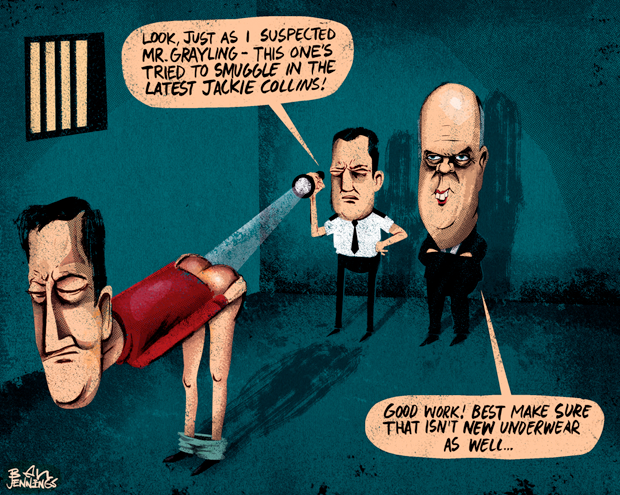

And then occasionally something explodes. A week and a half ago I saw Frances Cook, of the Howard League for Penal Reform, a brilliant but little-understood campaign group, tweeting about justice secretary Chris Grayling’s Incentives and Earned Privileges scheme, which was brought in last November.

It was part of his attempt to look tough on prisoners, the latest chapter in a seemingly endless cycle of tabloid coverage of supposedly cushy prisoner life, followed by a draconian clampdown by the secretary of state and stubbornly high reoffending rates.

Justice secretaries, like all ministers, are far more interested in the views of tabloids than academic researchers. If they valued the latter, they would build small prisons in the local community so inmates kept regular contact with their families, structure internal learning programmes to improve literacy levels and up-skill people so that they don’t rely on crime once they get out. But they don’t listen to researchers. They listen to tabloids, so they end up trying to flex their muscles, which in Grayling’s case is not an agreeable image.

The purpose of the scheme is to make prisoners earn spending money through discipline and participating in their rehabilitation programme. They can then use this (tiny) amount of money to buy things like toothpaste, underwear or, if they want, books.

Core to this project, Grayling says, is the idea that parcels from family and friends must be stopped. The justice secretary has many reasons for this. Perhaps it is to stop gifts making his earned privileges redundant. Perhaps it is because it is impossible to securely scan all the parcels. Perhaps it is because the parcels are sometimes used for contraband. It is hard to tell, because he is prone to using any number of these excuses as he goes.

But regardless of the reason, the Ministry of Justice banned prisoners receiving books or magazines by mail. Books were now considered a reward, not a tool for rehabilitation.

I asked Frances to write politics.co.uk a blog post on it, with a focus on the restrictions on books. But I was in no particular rush. I figured it would be one of those worthy pieces we publish, which get a bit of an airing and some decent traffic for a couple of days, then respectably fade away. I didn’t bother writing a news story about it, given the policy was actually four months old. When she asked what the deadline was, I was rather flippant. “Whenever really,” I told her. “It’s not very time sensitive.”

I published it late on Sunday morning and went off for lunch. The first sign that something had happened came when I went to the loo and checked Twitter (always a dangerous juggling act). Billy Bragg and Caitlin Moran were tweeting it. ‘That’ll get some traffic in,’ I thought.

By the time I went to bed it has been retweeted by the great, the good and everyone in between. A petition had been launched on Change.org.

I talked to Frances on the phone. For someone from her perspective, it is strange when this happens. Groups like the Howards League deal with stories about people being killed in prison and no-one gives a damn. The campaigners and prison officer groups I’ve talked to have been taken aback by the reaction to the piece, and often not a little frustrated. Perhaps people should be more concerned about the fact that inmates are being locked up two-to-a-cell, forcing them to go through the grim humiliation of going to the toilet in front of each other, one told me.

Their problem was mine too: Why do some issues, which might ultimately be more trivial than others, go viral?

In this case it is to do with the almost-mystical power of books in the middle class imagination.

There is a trivial side to this – the bourgeois pretention around books as idol-worship, typified by the stigma around marking your spot by turning the corner of the page. It is a fetishisation of the book, as if Waterstones were one of those Middle Aged tradesmen flogging you a strand of Jesus’ hair. It’s nonsense. Books are nothing but a machine, a tool to get information from brain A to brain B. They are beautiful, but it is a beauty which survives quite well when stuffed into the back pocket of a pair of jeans or covered in coffee stains.

The novel allows access to characters inner life in a way film never can. It is the most empathetic of art forms. Political books, from Paine to Orwell, weigh heavily in the battle of ideas in a way other mediums struggle to match. Even seemingly turgid course text books stand as a tribute to people’s capacity for self-improvement.

These are all vital functions of the book which inmates could benefit from. But for most of them, the importance of books is more sombre and rudimentary. Two-thirds of ex-offenders have the literacy and numeracy levels of an 11-year-old. What they need, more than anything, is young adult literature – appealing, simply written novels which can improve their core reading skills. Perhaps that sounds patronising. It is not meant to be. It is meant to be realistic.

Supporters of the Grayling policy in government told me I was kicking up a fuss so that some mugger could get his hands on a Harry Potter book. I accepted that proposition proudly. It is important that he does. It will do nothing to encourage him mugging someone and might just have a small role in discouraging it.

Anything that stands in the way of a prisoner reading anything is a lunatic act. It costs them more and it costs us more.

This article was posted on March 27, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

25 Mar 2014 | Digital Freedom, Events

(Image: Shutterstock)

Index on Censorship, in association with Doughty Street Chambers, invites you to attend our high-level panel discussion asking who runs the internet?

At a moment when the revelations on NSA and GCHQ mass surveillance are opening up a wide debate about our digital freedoms, our panel will discuss how free the net is today, and the main challenges that lie ahead. In the next couple of years, major international summits will debate new rules on internet governance, and whether to adopt a top-down approach as favoured by China and Russia, or maintain a more open, multistakeholder networked approach. Meanwhile, from the EU to Brazil, reactions to the Snowden’s revelations of mass snooping suggest there is a growing risk of fragmentation of the internet, with calls for forced local hosting of data.

We are delighted to be hosting speakers:

Bill Echikson – Head of Free Expression EMEA, Google

Richard Allan – Head of Europe, Middle East and Africa, Facebook

Tusha Mittal – formerly a correspondent for Tehelka and currently a Fellow at the Reuters Institute, Oxford University

Kirsty Hughes – CEO, Index on Censorship

The panel will make short introductory remarks ensuring plenty of time for a lively Q&A session.

The event will be held at Doughty Street Chambers (53-54 Doughty St, London WC1N 2LS) on Wednesday 2nd April 6-7.30pm, followed by a drinks reception. To RSVP please fill in your details here. If you have any questions please contact Fiona Bradley ([email protected]).