25 Mar 2014 | Americas, Europe and Central Asia, Events, United Kingdom, United States

Over a year after the Leveson report came out, regulation of the British press is still a question of intense debate. Meanwhile, the NSA/Snowden revelations – and the related detention of David Miranda (supported recently by British courts) – open up core questions of how investigative and public interest journalism can function in a world of mass surveillance. In the US, while Guardian editor-in-chief Alan Rusbridger rightly praises the first amendments, Obama himself has a growing reputation as a president who has pursued sources and journalists through the courts.

Join us on a Google Hangout with Guardian Digital journalist, James Ball (now based in New York) and LA Times London correspondent, Henry Chu, hosted by our Editor, Online and News, Sean Gallagher for a lively debate around the media freedom on either side of the Atlantic.

The recording will be broadcast live via Index’s Google+ and YouTube accounts from 10am (EST)/ 2pm (GMT) on Wednesday 26th March. Get involved in the discussion on our Twitter feed and website. Visit the Google+ page here and the YouTube page here.

26 Feb 2014 | Academic Freedom, Comment, Guest Post, Religion and Culture, United Kingdom

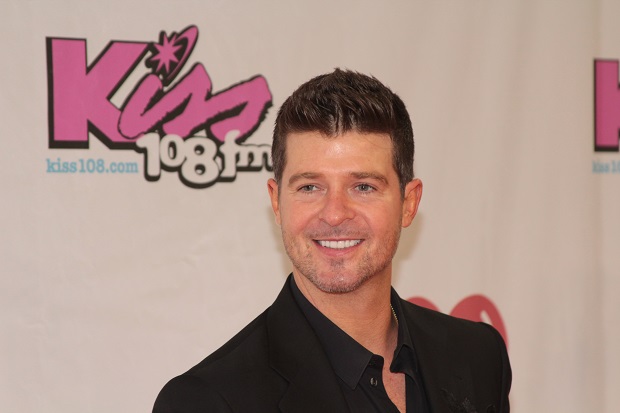

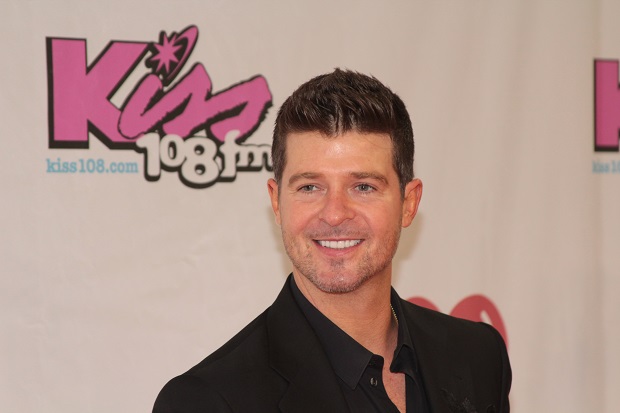

Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines song has been banned in at least 20 student unions after it was released in March 2013. (Image: George Weinstein/Demotix)

I consider myself to be privileged to have the job that I have-I am a university lecturer who teaches Popular Music Culture to undergraduates and post-graduates. This is a subject that is popular among students because the majority of them like music and have an opinion on it. What I love most about my job is the range of interesting conversations my students and I have around popular music and its impact on culture, politics and society.

Music is ubiquitous and it touches people of all cultures, classes and creeds in a multitude of ways. What comes out of the discussions I have highlights both the joy and the anger it can evoke. Some of those discussions can bring forward some sensitive, awkward and challenging opinions and issues but what they do succeed in doing is highlighting issues that we as adults can explore, discuss, argue, rationalise and at time agree to differ on-but in a mature and accepting way, appreciating that we are all different.

So during my lecture on popular music and gender back in November 2013 I opened up a discussion around Robin Thicke’s summer release “Blurred Lines”. I feel no real need to go into any great detail about the fastest selling digital song in history and biggest single hit of 2013. Why? Because the controversy surrounding this song, such as misogynistic positioning with “rapey” lyrics that excuse rape and promote non-consensual sex and, among many other accusations, the promotion of “lad culture”, is abundant on the internet.

My students’ views on this song, and accompanying video mixed with both females and males defending the song and Thicke’s counter argument of it – promoting feminism, it being tongue in cheek and a disposable pop song – to those who, again both male and female, just wanted to castrate him for putting women’s rights and equality back into the dark ages.

Now the scene in the lecture theatre had been set I wanted to garner from them views on what I considered to be equally, if not more important – the issue that over 20 university student unions in the UK had banned the song from being played in their student union bars and union promoted events. This includes the prevention of in-house and visiting DJs playing it on student union premises and ,in some cases, the song not being aired on student union radio and TV stations’ playlists. In their defence the majority of these universities decided to ban after complaints from some of their students, but I am yet to determine whether all these universities reached this decision after an open and democratic process of consensus through voting or otherwise.

What I did find interesting among the many statements from presidents and vice-presidents of the student unions was one given to the New Musical Express, in November 2013, by Kirsty Haigh, the vice president of Edinburgh University Student Association.

The decision to ban ‘Blurred Lines’ from our venues has been taken as it promotes an unhealthy attitude towards sex and consent. EUSA has a policy on zero tolerance towards sexual harassment, a policy to end lad culture on campus and a safe space policy-all of which this song violates”.

However what Haigh does not go on to explain is exactly how this song does that. I am also intrigued by the comment about a policy to end ”lad culture” as Haigh does not allude to a clearly defined set of parameters specifying what counts as ”lad culture/banter”. One might ask if identifying a specific gender (lad) is this not targeting and discriminating against that gender?

I am struggling to find what constitutes ”lad culture” as opinions differ, however the National Union of Students’ That’s What She Said report published in March 2013 defines it as: “a group or ‘pack’ mentality residing in activities such as sport and heavy alcohol consumption and ‘banter’ which was often sexist, misogynistic, or homophobic”. But does lad culture equate to sexual harassment-is there a connection or is this creating guilt by association? Some critics claim that ”lad culture” was a postmodern transformation of masculinity, an ironic response to ”girl power” that had developed during the noughties.

Allie Renison’s article Blurred lines: Why can’t women dance provocatively and still be empowered?, published in The Telegraph in July 2013, states that “Teenage girls and grown women spend countless hours confiding in each other about the finer details of physical intimacy, and I can safely say that even without a sex-obsessed pop culture this would still be the case.”

This has to some degree been confirmed by one of my students who is a member of the university girls’ hockey team and girls’ football team. She says that they go out as a group, taking part in activities such as sport and heavy alcohol consumption and banter which is often sexist and misandry and involves intimate commentary on the male anatomy and men’s sexual prowess.

So would that then constitute “ladette” culture or “girl power” culture? Do EUSA have a policy to end ladette culture on their campus?

But this isn’t really the core issue here; the issue is around censorship on campus, what constitutes a fair and balanced approach to these issues and where you draw the lines. Thirty years ago student unions were complaining about, and rallying against, censorship-now they are the ones doing the censoring. So where does this leave the issue of censorship?

Starting with music, has Blurred Lines been singled out or do those twenty university student unions have a clear policy on banning songs that might include Prodigy’s Smack My Bitch Up, Jimi Hendrix’s Hey Joe (condoning the shooting of women who cheat on their men), Robert Palmer’s Addicted To Love (the lyrics could be seen to suggest date rape), Rolling Stones’ Under My Thumb, or Britney Spear’s Hit Me Baby One More Time? The list could go on and on, including songs that incite violence, racism or revolution. Do student unions around the country have concise and definitive lists of songs that should be banned or censored or is it a matter for a small group of elected people? And when you leave a group of people to act as moral arbiters then how do you control their decision making power?

Did we not collectively settle this matter in the 90s? Didn’t we conclude that outrage over pop music is a music marketer’s dream and inevitably increases sales for the artist? Aren’t popular music lyrics supposed to be challenging, full of danger and ambiguity? And do we only stop at popular music?

It could be argued that Mozart’s Don Giovanni revels in the actions of a rapist as does Britten’s Rape of Lucretia, and what of literature, do we ban Nabokov’s Lolita, Oscar Wilde’s Salome? Shouldn’t student unions be picketing concert halls, storming the libraries and art collections of universities and start demanding the removal of offensive material or at worst the burning of books and paintings in homage to a misguided Ray Bradbury envisioned cultural pogrom? If you are going to start banning or censoring cultural artefacts then please at least have some sort of consistency otherwise you leave yourself open to criticism.

So is this censorship? I would argue it is. If policy prevents a visiting DJ from playing a particular song at a student union bar, because some people do not approve of it, then that is censorship. I myself do not disagree with the criticism of the lyrical content of Blurred Lines, or condone them, though one could argue about their potential polysemic interpretation. What this highlights is perhaps an inconsistency in the processes of censorship by the student union.

Working in a university, I strongly believe that one of the core purposes of the academy is to create a space to allow young adults, on their journey of personal development, to explore their own opinions and prejudices, while considering those of others. A space where they can hear a multitude of views and draw their own conclusions from them; engage in constructive debate, work these issues through. Universities, of all places, should foster a culture of free speech and free expression wherever reasonably expected. Yes, there are always going to be challenges to what is appropriate and acceptable, whatever those challenges are the banning or censoring of material always has to be done within the law. That is how we develop as individuals and a society.

This article was published on February 26, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

21 Feb 2014 | News

To: All Governments

From: Index on Censorship

Index on Censorship here. We’ve noticed some you have had trouble telling the difference between terrorists and journalist lately (yes, you too Barack: put the BlackBerry down). So we thought as people with some experience of the journalism thing, we could offer you a few handy tips to refer to the next time you find yourself asking: journalist or terrorist?

Have a look at your suspect. Is he carrying a) a notebook with weird squiggly lines on it, or b) an RPG-7. If the latter, odds on he’s a terrorist. The former? Most likely a journalist. Those squiggly lines are called “shorthand” – it’s what reporters do when they’re writing things down for, er, reporting. It might look a bit like Arabic, but it’s not, and even if it was, that wouldn’t be a good enough reason to lock the guy up.

A journalist

Still not clear? Let’s move on to the questioning part.

Questioning can be difficult. Your modern terrorist will be highly committed, and trained to withstand even your steeliest glare (and whatever other tactics you might use, eh? LOL! Winky Smiley!). So it may be difficult to establish for certain whether he or she is in fact a terrorist by simply asking them. They might even say they are a journalist, when actually they are terrorists! Sneaky! But there are some ways of getting past this deviousness.

Does your suspect have strong feelings about unpaid internships and their effect on the industry? Or “paywalls” and profit models? Your journalist will pounce on these question in a way that may be quite scary to watch, and keep you there talking about it long after you’ve told her she’s free to go. Your terrorist is not as bothered by these issues, generally, though may accept that it is very difficult for kids to get on the terror ladder these days and nepotism is not an ideal way to run a global bombing campaign.

A terrorist

Ask your suspect if he spends too much time on Twitter: If he gets defensive and says something along the lines of “Yes, but the fact is it’s justified. Stories break on Twitter. It’s not just all hashtag games and…” (again, this could go on for several hours, and will most likely end up being all about hashtag games), then he’s a journalist. [Note: If your suspects seem to spend a lot of time getting into Twitter spats with the Israel Defence Force, they may be a bit terroristy].

Does your suspect look stressed? Like, really, really stressed? Probably a journalist.

Finally, just try saying the phrase “below the line”. If you get a slightly confused look, you’ve probably got a terrorist. If there is actual wailing and gnashing of teeth, journalist.

Now let’s go over why you might be making this mix up. This is where a lot of people get confused, so we’ll be as clear as possible, but do keep up.

Terrorists generally hold quite extreme views which, it’s fair to say, most of us probably do not agree with. However, this does not mean that anyone you disagree with is a terrorist. Or, importantly, that someone who’s spoke to someone who you disagree with is a terrorist.

We understand that this can be quite a difficult point to get your head around, so here’s an example: If, say, a large, international news organisation reports on things you’d rather they didn’t, in a way you don’t like, this does NOT make them a “terrorist organisation”. The people working for them are NOT terrorists “broadcasting false news that harms national security”.

Sometimes, journalists will cover the activities of terrorist organisations, like al-Qaeda. This, however, does not automatically make them their “media man”. Get this — you can even interview members of a terrorist organisation without actually being a terrorist yourself.

Similarly, if someone has something that you want back, that doesn’t mean you get to use terrorism laws to get it, even if you think that thing is very, very important. And yes, even if they intend to use that thing to write stories about you.

Keep these basic ideas in mind and we can almost guarantee you’ll never make the embarrassing mistake of calling journalists terrorists again. Any doubts? Call us. We’re here to help.

The Index team

This article was posted on 21 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

20 Feb 2014 | Europe and Central Asia, News, United Kingdom

The panel from left to right: Gavin Millar QC, Tom Phillips, Padraig Reidy, Jonathan Heawood and Gill Phillips (Image: Georgia Hussey)

A new press regulator, with or without statutory underpinnings, would not stop another scandal like phone hacking from happening, an Index on Censorship panel said yesterday. The panel, consisting of Gill Phillips (Legal Director, Guardian Media Group), Gavin Millar QC (Doughty Street Chambers), Jonathan Heawood (Director of the Impress Project), and Tom Phillips (Senior Writer, Buzzfeed UK), chaired by Padraig Reidy, spoke at a Doughty Street Chambers and Index on Censorship debate on press freedom in the UK after the Leveson inquiry.

“In terms of the institutions that failed over phone hacking, the Press Complaints Commission doesn’t even make it onto the podium,” said Tom Phillips. “So the idea that any kind of regulation was ever intended to be the solution to this is missing a whole bigger picture.”

If you set up a system to stop something “human ingenuity and imagination” will find a way to get around it, said Gavin Millar QC. He added that the best regulation “has to come from the heart”, and was worried about the complicated rules surrounding regulation taking the responsibility away from those “who are putting the stuff out.”

Jonathan Heawood argued that we can make press abuses “less likely” though a “good, intelligent, intelligently applied regulator” and “sufficiently enforced, sufficiently clear sanctions”. He added that regulation is “part of the solution” to improve conditions allowing public interest journalism to flourish.

Press regulation took centre stage at the event, but wider issues of press freedom were also discussed. Gavin Millar pointed out how the UK’s debate on press freedom and press regulation may be perceived in authoritarian countries, while Tom Phillips warned that ignoring the evolving social norms of the internet age bad is for press freedom. Gill Phillips argued that while the UK isn’t as bad on press freedom as some other countries, “where we’re going” and “the threat of criminalisation that effects every day journalism” is worrying.

The event took place ahead of the release of Index on Censorship’s policy paper Life after Leveson: British media freedom in 2014. The paper acknowledges that the recent change in libel law was good for this country’s press freedom, “the record of successive governments have been far from perfect” and “there are still several areas where this government can act to safeguard the free press and free speech more broadly in the coming year.”

It was a timely discussion, as yesterday the High Court dismissed David Miranda’s challenge to his detention at Heathrow under the Terrorism Act in August. It was also the day former News of the World editor Rebekah Brooks took the stand in the ongoing hacking trial.

“The [Miranda] judgement has some wide ranging views downgrading journalism in the 20th century that I find personally bizarre,” said Philips. Millar said the judgement shows how the “remaining tendency of government using the possibility of court proceedings against newspapers to stifle the publication of state secrets” has a “chilling effect” on press freedom.

The sold-out event encouraged audience interaction, which made for a lively and at times heated, debate. One comment from the floor argued the panel had missed the point — that the debate was about press abuses, and a regulator was the minimum step that had to be taken. Another audience member questioned the press calling for regulation of other industries, but not wanting to be regulated themselves. The Guardian’s Roy Greenslade argued that we need to separate those issues of press abuse that can be tackled through the law and those that must be tackled by self-restraint on the part of the media. Observer columnist Peter Preston said the Royal Charter regulator would be part of a “conspiracy of chaps”.

The discussion also took place on Twitter, under the hashtag #LifeAfterLeveson

This article was published on 20 February 2014 at indexoncensorship.org