17 Dec 2013 | News, United Kingdom

Even after months of bitter opposition from the charities on the receiving end of the British government’s gagging bill, ministers are refusing to accept their reforms are threatening to undermine the “very fabric of democracy”.

Even after months of bitter opposition from the charities on the receiving end of the British government’s gagging bill, ministers are refusing to accept their reforms are threatening to undermine the “very fabric of democracy”.

That is the worry from the alliance of charities and other campaigning groups who will be hit by changes being pushed through in what the government insists should be called the “transparency bill”.

Such is the scope of the reforms in the legislation, which is now working its way through the Lords, that a whole range of campaigning activity will face intimidating regulation – and all the strangling paperwork that goes with it.

Democracy is about a struggle for power between competing political parties. But the electorate can only make up its mind if third-party groups make their voices heard on the most important public policy issues of the day.

If the government gets its way it is going to become much harder for that to happen. The list of groups which will be affected is endless: those attempting to save a threatened local hospital, or block the High Speed 2 rail project in constituencies on the proposed route, or trying to combat extremism in constituencies where far-right parties are threatening to make progress, are all set to be affected. There are many, many more examples.

Ministers claim they only ever wanted to make life tougher lobbying groups, rather than make their work virtually impossible. “It doesn’t matter what the bill was meant to do,” Baroness Hayter, the Labour frontbencher leading the fight against the bill in the Lords, says in reply. “Its intent may be transparency, but the effect of it is what’s worrying.”

The opposition’s complaints about the bill have forced minor concessions here and there. Ultimately, though, none of them change the fact that if the gagging bill passes it will be much, much harder to raise important issues just at the moment when they need to be highlighted.

Peers took over the struggle from MPs this autumn. They didn’t look to be making much progress until Lord David ‘Rambo’ Ramsbotham tabled a procedural motion which would have slowed up the bill’s progress through the Lords. A governmental panic ensued. Ministers met with Ramsbotham three times in a single morning. With the coalition facing defeat if it came to a vote, a six-week hiatus was announced.

It was a miserable concession. Opponents, who had wanted a pause of at least three months, weren’t placated at all. They were frustrated that, instead of holding a formal consultation, officials instigated a series of meetings with affected parties. One charity campaigner said he was asked again about the objections he’d already raised. “They said ‘oh no, it couldn’t possibly apply’,” he remembered. “I said, ‘are you sure?'” The ministers replied: “Well, yes, maybe…”

It is that uncertainty which remains at the heart of the issue. There is no single measure which is being fought over. Instead the cumulative effect of the reforms is what Hayter calls “tying them in red tape” – a combination of measures which makes it much more likely many small-scale groups will simply decide not to bother campaigning at all.

“The danger is the regulation it introduces will be so complex, ambiguous and demanding in terms of time that many small organisations will just not do it,” says Pete Mills, policy and research officer at Unlock Democracy. “They’ll be so worried about falling foul of the rules they’ll just stop campaigning altogether. That would be very dangerous in the run-up to an election where this kind of debate is most valuable.”

This week the bill is receiving detailed scrutiny in the Lords. After two reports from the Commission on Civil Society and Democratic Engagement demanding changes, the government does look set to increase the spending threshold over which campaign spending becomes regulated. By how much will, of course, be critical. Ministers are also conceding they will hold a review of the system after the next general election.

Both these promises have been met with cynicism from Labour. It is enraged by the government’s failure to amend the bill this week. Instead the changes are likely to come early in the new year, when – with the disorganised crossbenchers slowly returning from the festive break – ministers are more likely to win a vote.

This is how the bigger-picture changes in the bill could become law. We could see an extension of what constitutes ‘controlled expenditure’ to cover a much wider range of activities including rallies, meetings and polling. Every group campaigning as a coalition could be forced to register the total spending of the coalition as a whole.

“We are talking about something which faces a criminal sanction if you break it, so I think one is right to expect a degree of certainty,” complains James Legg of the Countryside Alliance. He believes his organisation’s campaign against fox-hunting in the 2005 election would have been effectively shut down had the coalition’s changes been in place.

Legg fears that nightmare could become reality in 2015. “The government could simply say ‘we’ll introduce that now’, and that would shut us up,” he says.

The battle against the ‘gagging bill’ is not yet lost, but it’s a bleak outlook for Britain’s democracy this midwinter.

14 Nov 2013 | Events, United Kingdom

In light of the recently passed Californian law allowing minors to delete any of their online activity, Index organised a Google Hangout in association with student newspapers York Vision and The Student Journals, on whether young people should have the right to be forgotten on social media.

Watch the discussion between York Vision editor Patrick Greenfield, Student Journals editor Amy Ashenden and Index’ Alice Kirkland and Milana Knezevic below.

What do you think? Have your say in the comments or tweet us at @IndexCensorship.

8 Nov 2013 | Digital Freedom, News, United Kingdom

(Photo: David von Blohn / Demotix)

This week saw some movement in the debate over NSA and GCHQ surveillance, and a court case that could have very serious consequences.

The court case first. One Wednesday and Thursday, the court of Appeal held a judicial review into the use of Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act taken by David Miranda, partner of journalist Glenn Greenwald. Miranda was detained in transit at Heathrow airport under Schedule 7 while carrying encrypted documents that had emanated, ultimately, from whistleblower Edward Snowden.

The question was whether the authorities, knowing who Miranda was, what he was likely to be carrying, and his purpose for holding the documents, had a right to detain him under that particular piece of law.

It’s quite technical, but it comes down to whether carrying the documents Miranda was carrying could be seen as an act of terrorism or an act that could potentially aid terrorism (as the government and police argue) or as part of a journalistic enterprise (in essence, what Miranda is arguing).

Index and other organisations have weighed in in support of the argument put forward by Miranda’s team, as we worry that a ruling against Miranda could have serious implications. Journalism can often operate in dubious areas: whether material “leaked” or “stolen” for example, is a question that can have very different answers depending on who you ask.

In this case, the UK government very clearly maintains that the documents have been stolen and should be given back. Furthermore, they believe that they could fall into the hands of the wrong people – terrorists or hostile states, if not in the control of security services.

That, by the way, was very interesting indeed. The Home Office’s case suggested Russia, where Edward Snowden has been granted temporary asylum, is a hostile state.

The other side of this argument is that Miranda was assisting in journalism. This will involve, on occasion, having documents others would rather you did not have. The act of journalism is to sift these documents and decide where the stories lie within them. There was considerable back and forth on what “responsible journalism” constitutes during the hearing, but ultimately, it must be up to an editor what goes into a paper.

The Guardian’s Alan Rusbridger maintains he has acted with absolute responsibility. And GCHQ have as yet not claimed that agents have been endangered as a result of the Guardian’s revelations.

But at a hearing of parliament’s Intelligence and Security Committee (the ISC) on Thursday, spy chiefs insisted that Britain’s enemies were “rubbing their hands with glee” at the Guardian’s publications, and that terrorist chatter online had “gone dark” (i.e. more difficult to trace) since the first stories had appeared.

What next for the surveillance debate? The ISC performance was generally held to be weak. Rory Stewart MP has suggested it be composed more democratically, with an opposition MP at its head. The general demand on surveillance seems fairly low key: more scrutiny, less scope for random snooping.

Meanwhile the judges will mull over the Miranda case, and, we hope, come to the conclusion that whatever the young Brazilian was doing, it wasn’t terrorism.

This article was originally posted on 8 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

7 Nov 2013 | Africa, News

1) Angola

Manuel Chivonde Nito Alves was held in solitary confinement for printing t-shirts. Image from his Facebook page.

Angolan 17-year-old Manuel Chivonde Nito Alves went on hunger strike on Tuesday, following his arrest on 12 September for printing t-shirts with the slogan “Out Disgusting Dictator”. The message was aimed at the country’s President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who has held power in since 1979. The shirts were to be worn at a demonstration in the capital Luanda, highlighting corruption, forced evictions, police violence and lack of social justice under dos Santos’ regime. Nito Alves has been charged with “insulting the president”, and has now spent almost two months in detention – parts of it in solitary confinement. His family were barred from seeing him, and three weeks went by before he was allowed to speak to a lawyer. The hunger strike is in protest at his “unjust and inhumane treatment”.

2) Belarus

Yury Rubstow wearing the t-shirt that landed him in prison. (Image Viasna Human

Rights Centre)

On Monday, Belarusian opposition activist Yury Rubstow was sentenced to three days in jail for wearing a t-shirt with the slogan “Lukashenko, go away” on the front, and “A four-time president? No. This is not a president but an impostor tsar” on the back.” The message was aimed at the country’s dictator Alexander Lukashenko, during an opposition protest march. He was found guilty of disobedience to police officers under Article 23.4 of the Civil Offenses Code.

3) Swaziland

In 2010, Sipho Jele, a member of Swaziland’s People’s United Democratic Movement, was arrested for wearing a t-shirt supporting the party during a May Day parade. He was arrested under the country’s Suppression of Terrorism Act, and died in custody. The police said he had hanged himself, while the party say the police of killed him.

4) Egypt

The Rabaa symbol displayed at a protest in Turkey (Image Bünyamin Salman/Demotix)

In September, three Egyptian men were arrested for wearing t-shirts emblazoned with the Rabaa symbol. A hand holding up four fingers, it is widely used by those opposing Egypt’s interim military-backed government, and the coup that ushered in in. Mohamed Youssef, the country’s kung fu champion, was also suspended by the national federation for wearing a similar t-shirt during a medal ceremony.

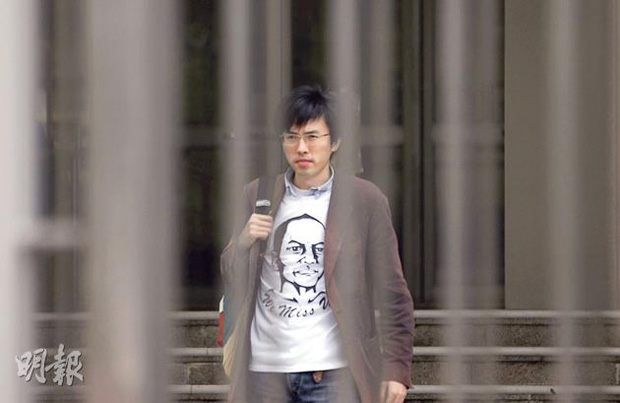

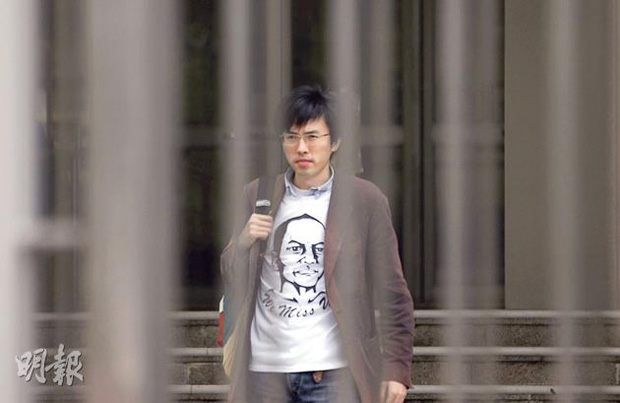

5) Hong Kong

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

An activist from Hong Kong was arrested last December for throwing a t-shirt at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit almost six month earlier, on 1 July. League of Social Democrats Vice Chairman Avery Ng threw a t-shirt with a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang, a Tiananmen Square activist who died under suspicious circumstances only weeks before the visit. Ng was charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place”.

6) Malaysia

Malaysian protester wearing a Bersih shirt. (Image Syahrin Abdul Aziz/Demotix)

In June 2011, Malaysian police arrested 14 opposition activists for wearing t-shirts promoting a rally in Kuala Lumpur calling for election reform. The shirts carried the slogan “bersih” which means “clean”, and is the name of one of the groups behind the protest. Authorities claimed the demonstration was an “attempt to create chaos on the streets and undermine the government”, and they were therefore within their rights to arrest the protesters. They also confiscated t-shirts from the group’s headquarters.

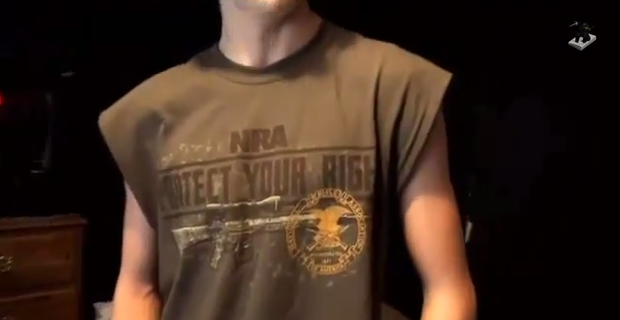

7 & 8) The US

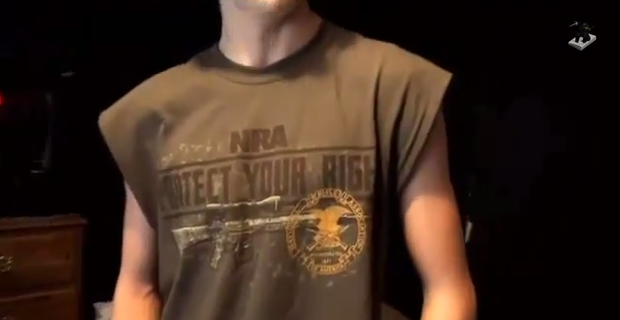

Jared Marcum wearing his NRA t-shirt in a TV report. (Image Youtube)

A 14-year-old student from West Virginia was in April suspended from school and subsequently arrested for refusing to remove a t-shirt supporting the pro-gun National Rifle Association. Jared Marcum was charged with “obstructing an officer” and faced a $500 fine and up to one year in prison.

On the flip side, a Tennessee man was arrested for wearing a t-shirt in support of stricter gun control laws. Stanley Bryce Myszka was wearing a shirt that read “Has your gun killed a kindergartener today?” at a shopping centre, following the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. He was approached by security guards, who called the police when he when he refused to remove the shirt. He was also banned from the shopping centre for life.

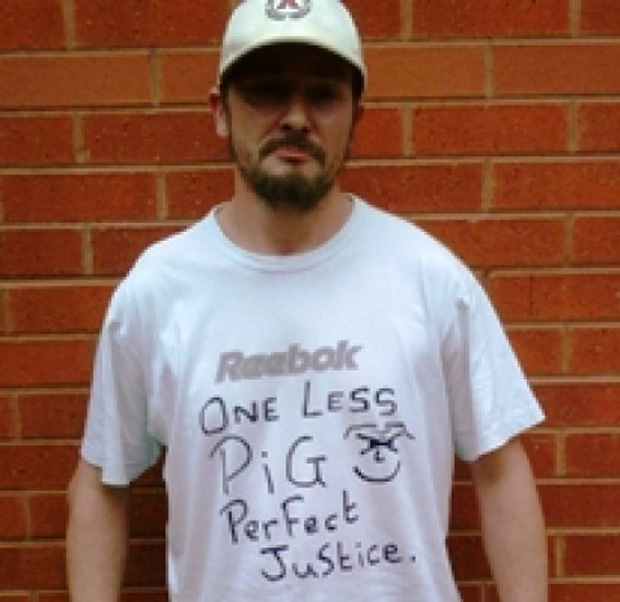

9) United Kingdom

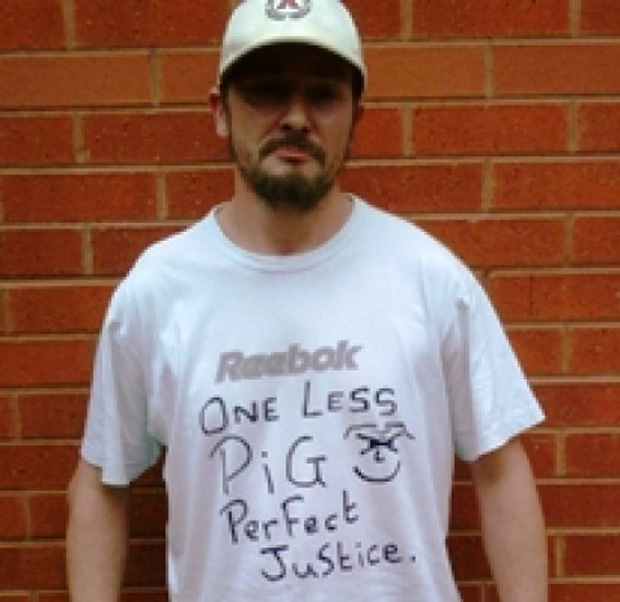

The front of Barry Thew’s t-shirt. (Image Greater Manchester Police)

A Manchester man was in October 2012 sentenced to eight months in prison in part for wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with offensive comments referencing the murders of two policewomen. Barry Thew had written “One less pig; perfect justice” on the front of his t-shirt and “killacopforfun.com haha” on the back. While four months of the sentence was handed down for breach of a previous suspended sentence, he was charged on a Section 4A Public Order Offence for the t-shirt incident.

Even after months of bitter opposition from the charities on the receiving end of the British government’s gagging bill, ministers are refusing to accept their reforms are threatening to undermine the “very fabric of democracy”.

Even after months of bitter opposition from the charities on the receiving end of the British government’s gagging bill, ministers are refusing to accept their reforms are threatening to undermine the “very fabric of democracy”.