7 Nov 2013 | Africa, News and features

1) Angola

Manuel Chivonde Nito Alves was held in solitary confinement for printing t-shirts. Image from his Facebook page.

Angolan 17-year-old Manuel Chivonde Nito Alves went on hunger strike on Tuesday, following his arrest on 12 September for printing t-shirts with the slogan “Out Disgusting Dictator”. The message was aimed at the country’s President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who has held power in since 1979. The shirts were to be worn at a demonstration in the capital Luanda, highlighting corruption, forced evictions, police violence and lack of social justice under dos Santos’ regime. Nito Alves has been charged with “insulting the president”, and has now spent almost two months in detention – parts of it in solitary confinement. His family were barred from seeing him, and three weeks went by before he was allowed to speak to a lawyer. The hunger strike is in protest at his “unjust and inhumane treatment”.

2) Belarus

Yury Rubstow wearing the t-shirt that landed him in prison. (Image Viasna Human

Rights Centre)

On Monday, Belarusian opposition activist Yury Rubstow was sentenced to three days in jail for wearing a t-shirt with the slogan “Lukashenko, go away” on the front, and “A four-time president? No. This is not a president but an impostor tsar” on the back.” The message was aimed at the country’s dictator Alexander Lukashenko, during an opposition protest march. He was found guilty of disobedience to police officers under Article 23.4 of the Civil Offenses Code.

3) Swaziland

In 2010, Sipho Jele, a member of Swaziland’s People’s United Democratic Movement, was arrested for wearing a t-shirt supporting the party during a May Day parade. He was arrested under the country’s Suppression of Terrorism Act, and died in custody. The police said he had hanged himself, while the party say the police of killed him.

4) Egypt

The Rabaa symbol displayed at a protest in Turkey (Image Bünyamin Salman/Demotix)

In September, three Egyptian men were arrested for wearing t-shirts emblazoned with the Rabaa symbol. A hand holding up four fingers, it is widely used by those opposing Egypt’s interim military-backed government, and the coup that ushered in in. Mohamed Youssef, the country’s kung fu champion, was also suspended by the national federation for wearing a similar t-shirt during a medal ceremony.

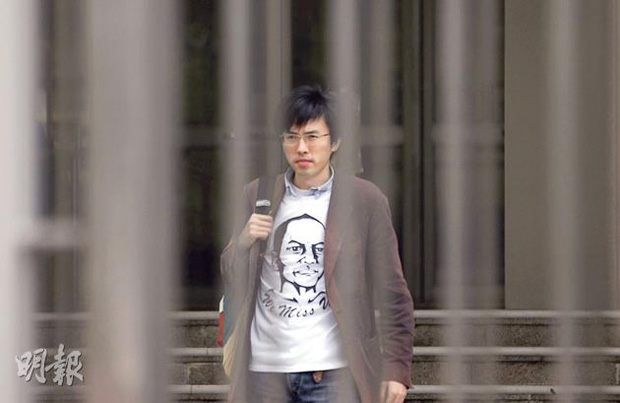

5) Hong Kong

Avery Ng wearing the t-shirt he threw at Hu Jintao. Image from his Facebook page.

An activist from Hong Kong was arrested last December for throwing a t-shirt at former Chinese president Hu Jintao during an official visit almost six month earlier, on 1 July. League of Social Democrats Vice Chairman Avery Ng threw a t-shirt with a drawing of the late Chinese dissident Li Wangyang, a Tiananmen Square activist who died under suspicious circumstances only weeks before the visit. Ng was charged “with nuisance crimes committed in a public place”.

6) Malaysia

Malaysian protester wearing a Bersih shirt. (Image Syahrin Abdul Aziz/Demotix)

In June 2011, Malaysian police arrested 14 opposition activists for wearing t-shirts promoting a rally in Kuala Lumpur calling for election reform. The shirts carried the slogan “bersih” which means “clean”, and is the name of one of the groups behind the protest. Authorities claimed the demonstration was an “attempt to create chaos on the streets and undermine the government”, and they were therefore within their rights to arrest the protesters. They also confiscated t-shirts from the group’s headquarters.

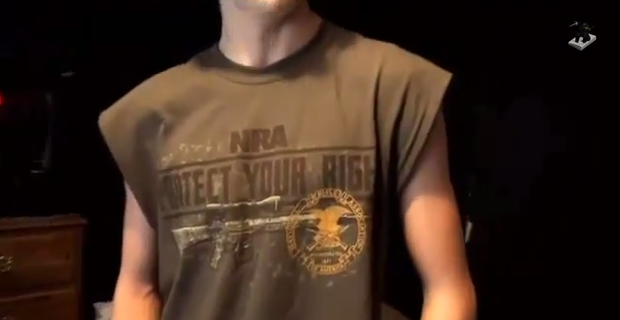

7 & 8) The US

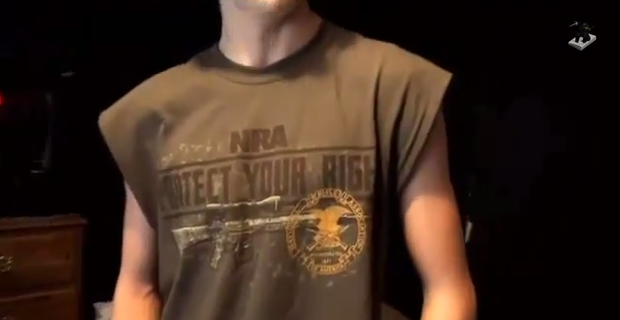

Jared Marcum wearing his NRA t-shirt in a TV report. (Image Youtube)

A 14-year-old student from West Virginia was in April suspended from school and subsequently arrested for refusing to remove a t-shirt supporting the pro-gun National Rifle Association. Jared Marcum was charged with “obstructing an officer” and faced a $500 fine and up to one year in prison.

On the flip side, a Tennessee man was arrested for wearing a t-shirt in support of stricter gun control laws. Stanley Bryce Myszka was wearing a shirt that read “Has your gun killed a kindergartener today?” at a shopping centre, following the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. He was approached by security guards, who called the police when he when he refused to remove the shirt. He was also banned from the shopping centre for life.

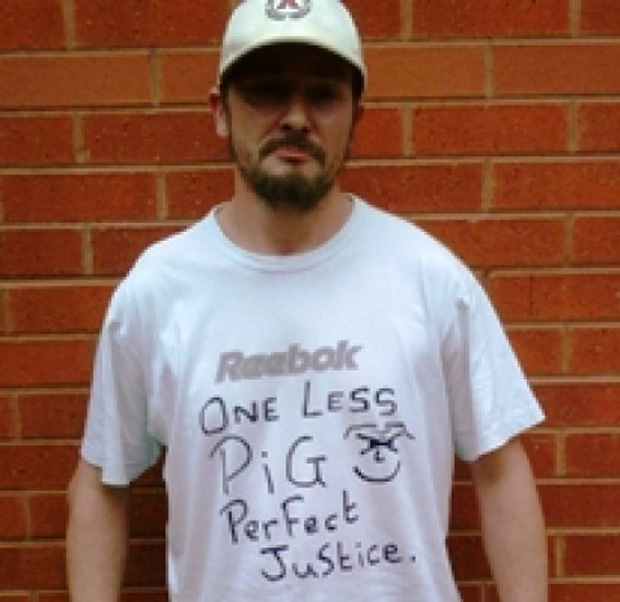

9) United Kingdom

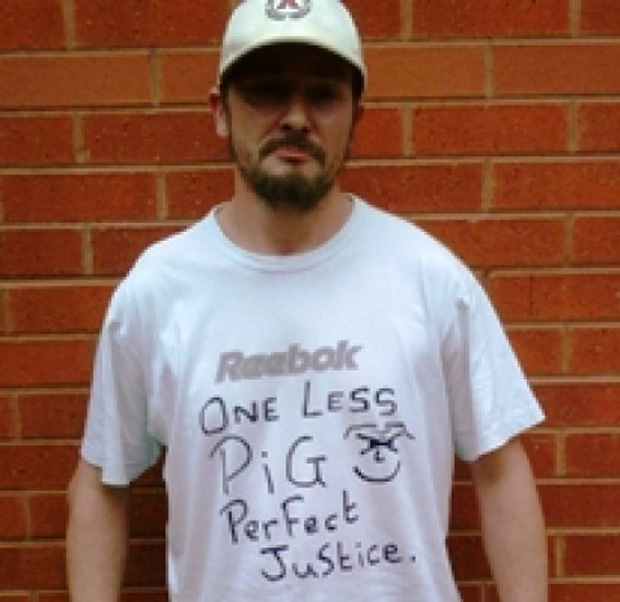

The front of Barry Thew’s t-shirt. (Image Greater Manchester Police)

A Manchester man was in October 2012 sentenced to eight months in prison in part for wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with offensive comments referencing the murders of two policewomen. Barry Thew had written “One less pig; perfect justice” on the front of his t-shirt and “killacopforfun.com haha” on the back. While four months of the sentence was handed down for breach of a previous suspended sentence, he was charged on a Section 4A Public Order Offence for the t-shirt incident.

18 Oct 2013 | Bulgaria, Digital Freedom, Germany, News and features, United States

On 30 September, Bulgarian-German author Ilija Trojanow was travelling from Brazil to the US for a conference on German literature. That was his plan, anyway. At the airport in Salvador da Bahia, he was told his entry to the US had been denied. No explanation was provided then, and none has been provided since.

On 30 September, Bulgarian-German author Ilija Trojanow was travelling from Brazil to the US for a conference on German literature. That was his plan, anyway. At the airport in Salvador da Bahia, he was told his entry to the US had been denied. No explanation was provided then, and none has been provided since.

Trojanow is one of the main forces behind a 74,000 strong and growing petition against mass surveillance. Initiated and signed by some Germany’s biggest writers, the petition argues the government is bound by the constitution to protect its citizens against foreign spying.

His experience in Brazil exploded in the German media, but Trojanow seems more bemused than anything else.

“It wasn’t bad enough that governments are spying on everybody!” he says with a laugh. “What this shows is that general attacks on everybody and not individual victims, are too abstract. An individual case, even if it’s a minor one, can get more attention.”

While the incident did create more discussion around mass surveillance and caused a spike in the number of signatures, there is no doubt the petition already had widespread support. The issue of mass surveillance seems to have struck a particular chord in Germany. Trojanow believes this is due to their history.

“East Germany more than any other country in the former Soviet block has discussed its secret service files. It has been a dominant issue in the media. The archives are easy to access. Germans know how horrendous it is when the secret service is not under real control.”

He also thinks the famous German efficiency shines through even in this case. Many felt that something needed to be done about the mass surveillance, and when Germans set out to do something, they do it properly.

“It is quite ironic,” he adds: “Germans had democracy beaten into them. They were educated in democracy by the US and the UK. It seems they were good students!”

Trojanov himself has long been interested in the issue of state surveillance, with his 2009 book “Freedom Under Attack”, for instance, becoming a bestseller in Germany. For him, the issue carries a more personal dimension. Growing up in a Bulgaria, parts of his family were engaged in the struggle against the communist authorities.

“I am in the situation now where I am able to read transcripts of what adults in my family were saying, as our apartment was bugged.”

“What you realise is that when you have the attention of the secret service pointed at you, whatever you do is in some way proof of guilt. Even completely innocent things become potentially implicating.”

The petition was formally presented to the German government on 18 September, back when when it had 63,000 signatures. A month and ten thousand additional names later, they have still have yet to receive any sort of official reply. Still open, Trojanow and his compatriots now plan to take it global. As he says, mass surveillance is a worldwide challenge and cannot be tackled simply by and within one nation.

“I don’t understand why we wait until situation is completely unbearable. You start safeguarding your freedoms when they are attacked on the edges.”

This article was originally posted on 18 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

8 Oct 2013 | News and features, Politics and Society, The climate crisis, United Kingdom, United States

(Photo Illustration: Shutterstock)

The continuing advance of climate science, as reflected in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s recently released Fifth Assessment Report, points ever more strongly to the need for an expedited phase-out of carbon emissions from fossil fuels. Only a fundamental transformation of the current energy system during the coming decades may make it possible to avert disastrous impacts of global climatic disruption.

Carrying out such a transformation would be a political, economic, and technological challenge under the best of circumstances. But it is made especially difficult by corporate and ideologically driven opposition — most notably, by pressure from fossil fuel production interests to protect their strategic position and set the terms for government policymaking.

The United States and Canada exemplify the power of the dominant energy interests. The governments of both countries strongly support the expansion of domestic fossil energy extraction, production, and export. But the collision between climate science and energy politics, and threats to freedom of communication, are playing out differently in the two countries.

With the Harper government in Canada, for years we have witnessed an ongoing repression of climate and environmental science communication by government scientists, along with systematic cutbacks of environmental research and data collection. “Harper’s attack on science: No science, no evidence, no truth, no democracy“, an excellent review and discussion in the May 2013 issue of the Canadian journal Academic Matters, itemized a series of moves by the Harper government to control or prevent the free flow of scientific information across Canada, particularly when that information highlights the undesirable consequences of industrial development. The free flow of information is controlled in two ways: through the muzzling of scientists who might communicate scientific information, and through the elimination of research programs that might participate in the creation of scientific information or evidence.

It appears that the issues on which government scientists are subjected to the tightest political control of communications include climate change, the Alberta tar sands, the oil and gas industry, and Arctic wildlife. In other words, issues on which free communication of scientific evidence could pose problems for corporate energy development interests.

The situation in Canada has driven government scientists to hold public protest rallies twice in the last year. In September, rallies in major city centers and on university campuses were held across the country.

“It isn’t the way science is supposed to be. It’s not the way science used to be, the way I remember it in the federal government,” IPCC vice-chair and retired Environment Canada scientist John Stone told The Guardian.

So the Harper government can be said to be following in the footsteps — even surpassing — the record of the former Bush-Cheney administration in the U.S., whose alignment with energy industry interests led them to misrepresent climate science intelligence and impede forthright communication by federal climate scientists.

In the U.S., the Obama administration presents a complex picture that differs from Canada in significant ways, but also suggests the problematic nature of government support for expanded fossil energy extraction and production. The administration appears susceptible to industry pressure aimed at playing down the environmental and societal consequences of fossil energy resource extraction and use.

After several years of near-silence on climate change at the highest levels of U.S. political leadership, in June President Obama finally gave a major public address on climate change (the first by an American president) and laid out a multifaceted Climate Action Plan. The plan focuses on actions that can be taken by the White House and Executive Branch in the absence of action by a Congress that is tied in knots, largely subservient to corporate energy interests, and with much of the Republican Party aligned with the global warming denial machine.

Under Obama, we see a more straightforward acknowledgement of climate science and assessments by the most credible experts, and more straightforward communication on climate by federal research agencies. The forthcoming National Climate Assessment, scheduled for release next spring, will address the implications of climatic disruption for the U.S., across geographical regions and socioeconomic and resource sectors (public health, water resources, food production, coastal zones, and so forth). The importance of national assessments for public discourse was underscored when the Bush administration, in collusion with nongovernmental global warming denialists, suppressed official use of and references to the first National Climate Assessment, which had been completed in 2000.

Yet, despite the numerous constructive action items in Obama’s Climate Action Plan, there appears to be a contradiction at the heart of Obama’s policy, as indicated by the administration’s adoption of what they call an ‘all of the above’ approach to energy development. Obama points to increased U.S. fossil energy extraction as a major accomplishment. U.S. energy development includes ‘mountaintop removal’ coal mining in Appalachia, large-scale coal strip-mining on public lands in the West, and increased coal exports; deepwater drilling for oil in the Gulf of Mexico, even in the wake of the BP oil blowout disaster in 2010, and quite possibly drilling in the Arctic Ocean off the coast of Alaska; and a dramatic increase during the past five years in natural gas production using directional drilling technology and hydraulic fracturing of shale deposits that cover a number of large areas across the country.

Natural gas from ‘fracking’ appears to be an essential component of the administration’s climate policy, i.e., relying on the ongoing trend of substitution of natural gas for coal in power plants in order to meet a 2020 goal for reducing U.S. carbon emissions. The Department of the Interior has proposed to open 600 million acres of public land to fracking. But fracking is controversial, raising concerns about contamination of drinking water in affected areas by chemicals used in fracking, large-scale use of water in drilling, air pollution, leaking methane greenhouse gas emissions, and industrial degradation of rural landscapes. Environmental groups have protested at the White House, calling for a moratorium on fracking on public lands.

There are sIgns that the administration may be allowing political pressure from the natural gas industry to compromise investigations by the Environmental Protection Agency into fracking contamination incidents. The EPA has pulled back from several high-profile investigations in a manner that raises questions about whether this indicates a pattern of failure to act on scientific evidence. When the EPA’s scientists found evidence that fracking was contaminating water supplies, the EPA stopped or slowed down their work in in Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wyoming.

“Not only does this pattern of behavior leave impacted residents in the lurch, but it raises important questions as to whether the agency is caving to pressure from industry, antagonistic members of Congress and/or other outside sources,” Kate Sinding at the Natural Resources Defense Council notes. “This trend also calls into serious question the agency’s commitment to conducting an impartial, comprehensive assessment of the risks fracking presents to drinking water—a first-of-its-kind study that is now in its fourth year, with initial results now promised in 2014.” The EPA recently announced that it has delayed the expected final date of this study until 2016 — Obama’s eighth and final year in office. Meanwhile, industry continues to create a fait accompli of radically expanded fracking operations.

Obama has adopted a forward-looking position on climate change. But his ‘all of the above’ energy policy, and particularly his full-speed-ahead support for shale gas fracking, raises the question of whether politics is impeding freedom of communication by government experts — and whether the EPA is thereby being impeded in doing its job of protecting the public against the environmental dangers of fossil fuel development.

This article was originally published on 8 Oct 2013 at indexoncensorship.org

19 Sep 2013 | Digital Freedom, News and features, Politics and Society, United States

David Carr recently reported in the New York Times that journalist Barrett Brown could face a 100-year prison term if he’s found guilty for linking to stolen information. He didn’t steal this information himself, nor did he post it online. He simply linked to it.

Brown is a dogged journalist who has done important and revealing reporting on the business of surveillance. His work has appeared in BusinessWeek, the Guardian, the Huffington Post and Vanity Fair. He has also served at times as a self-appointed spokesman for Anonymous, the leaderless Web collective of hackers and activists.

As a victim, he’s imperfect, Carr writes. Brown has struggled with substance abuse and by all accounts hasn’t always been easy to get along with. For example, he threatened an FBI agent and his family by name in a video he posted to YouTube.

Brown came to the government’s attention when he linked in a chat room to material Anonymous had posted online.

In recent years, Anonymous has hacked into the computer systems of a number of intelligence and surveillance firms who contract with the government and the biggest corporations. These firms helped craft elaborate campaigns to attack and discredit activists and journalists on behalf of corporate clients and have received huge government contracts for other projects.

By all accounts, Brown doesn’t have the technical ability or knowhow to have participated in the hacking that exposed these documents. But once they were released, Brown set up a research organization, Project PM, to sort through the documents and report on what they contained.

“The files contained revelations about close and perhaps inappropriate ties between government security agencies and private contractors,” Carr writes. But they also contained credit-card information and private emails.

When Brown linked to these files in a chat room, he “provided access” to stolen information, the government says. Prosecutors charged him with 12 counts related to identity theft.

The notion that linking to stolen material makes the linker a party to the original crime is absurd. And the severity of the charges is clearly meant to send a message to journalists and whistleblowers everywhere. Viewed in light of the Chelsea Manning case and the Edward Snowden leaks, the Brown case appears part and parcel of the government’s crackdown on activists who leak information and the journalists who report on them.

Carr reminds us that journalists frequently link to stolen documents. The Times’ most recent articleon the Snowden documents did so. The Electronic Frontier Foundation also points to a leak of congressional staffer passwords that many news organizations linked to. And this practice is only likely to expand.

“News organizations in receipt of leaked documents are increasingly confronting tough decisions about what to publish,” Carr writes, “and are defending their practices in court and in the court of public opinion, not to mention before an administration determined to aggressively prosecute leakers.”

The Committee to Protect Journalists responded in more forceful terms, arguing that the government’s handling of this case “threatens the nature of the Web, as well as the ethical duty of journalists to verify and report the truth.”

Indeed, in the U.S. and the U.K. we’ve seen shocking efforts to harass and intimidate journalistsworking on national security and surveillance issues. The Barrett Brown case follows a similar narrative.

When Brown posted the link to the Anonymous documents in a chat room, the government tracked him down at his mother’s home and tried to seize his laptop. When he and his mother refused to hand over the computer, the FBI threatened to throw Brown’s mother in jail. Here’s how the Guardian’s Glenn Greenwald describes the harassment:

Over the next several months, FBI agents continued to harass not only Brown but also his mother, repeatedly threatening to arrest her and indict her for obstruction of justice for harboring Brown and helping him conceal documents by letting him into her home.”

Brown’s mother eventually pled guilty but has yet to be sentenced. Brown lashed out at the FBI, threatening one agent by name, in the video he posted to YouTube. Those threats gave the FBI cause to arrest Brown and he has been in custody ever since.

While threats of this sort should be taken seriously, so too should the ongoing harassment of journalists and their families.

The New York Times story on Barrett Brown is important because it comes on the heels of a gag order that prohibits people involved in his case from speaking to the press. The legal fees for the case are expected to exceed $200,000 and an activist has established a defense fund.

Links are the connective tissue of the Internet. They enable us to share news, discover new information, dig deeper into issues and give credit to sources. The government’s effort to criminalize linking is akin to rewiring how the Internet works. It will have a chilling effect on how journalists report on sensitive government matters.

This case also has a bearing on all of us who post links to Facebook, tweet articles or blog about the news of the day.

This article was originally posted on 13 Sept 2013 at freepress.net and is reproduced here by permission.

On 30 September, Bulgarian-German author

On 30 September, Bulgarian-German author