3 May 2018 | Journalism Toolbox Spanish

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Tanto las virtudes como los peligros del patriotismo dependen de cómo se cuente la historia

“][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

Soldados, pilotos de las fuerzas aéreas y marines desenrollan una bandera estadounidense en una ceremonia de apreciación del ejército en un partido de los New York Jets contra los New England Patriots el 13 de noviembre de 2011, Sargento Sandall A. Clinton/Flickr

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

La declaración del Doctor Johnson acerca de que el patriotismo es el último refugio del sinvergüenza degrada en cierto modo uno de los sentimientos humanos más explosivos que existen. La declaración en cuestión da por supuesto que un presidente o primer ministro astuto podría manipular el amor a la patria para sus propios y egoístas fines. O, también, que las masas son tan ignorantes, y tan ciega su fe, que lo único que tiene que hacer el sinvergüenza es ondear la bandera, hablar de sangre y terruño, y las patrióticas ovejas lo seguirán donde a él le plazca.

Ocurre que el patriotismo no es tan sencillo. El sentimiento patriótico es una mezcla de multitud de elementos, y el amor a la patria es tan complejo y dubitativo como cualquier otro tipo de amor. Crea una narrativa de vida colectiva. Cuenta una historia de lo que une a personas dispares, y tanto las virtudes como los peligros del patriotismo dependen de cómo se cuente la historia. Es decir, que no es una mera representación de una nación o una cultura en concreto: es una representación que se logra por medio de la narrativa. Los elementos destructivos del patriotismo se deben a imaginar que hay un desenlace, un clímax catártico de la historia de un pueblo o una cultura; esto es, el momento en el que un acto decisivo cumplirá su destino al fin. Y el peligro que nos ha enseñado la historia es que este desenlace narrativo supone demasiadas veces negar o destruir a otro pueblo para experimentar la catarsis.

Las narrativas del patriotismo que son destructivas, los tipos de desenlace que por un lado agreden a otros y por el otro parecen hacer realidad un elemento de su narrativa, sostienen en particular una potente promesa para con grupos humanos divididos internamente o desorientados por fuerzas ajenas a su control. Según éstas, el patriotismo es el último recurso de los confundidos.

La noción de que esta historia en curso de la disonancia que compartimos podría resolverse de algún modo con un catártico acto destructivo me parece un problema real en la experiencia patriótica, y marca la experiencia social del patriotismo de hoy.

Una gran crisis patriótica de mi juventud surgió entre quienes, como yo, resistimos la guerra estadounidense en Vietnam en los años 60 y 70. Entonces, como ahora, EE.UU. no era la máquina interna bien lubricada que a menudo imaginan los extranjeros. Por entonces, el país estaba sumido en una explosión racial, el boom tras la II Guerra Mundial se había frenado temporalmente y la clase obrera blanca comenzaba a sufrir. La prosperidad estadounidense era, como ahora, la prosperidad de las élites.

Cuando EE.UU. intervino de forma decisiva en Vietnam a mediados de los 60, nuestro país sí contaba con una narrativa patriota de largo recorrido: EE.UU. aparecía como rescatador, salvando a los extranjeros de aniquilarse unos a otros. Esa narrativa patriota había dado forma a la lucha en ambas guerras mundiales, y justificó los enormes costes de librar la Guerra Fría. Vietnam parecía tratarse de un capítulo más en esta historia consolidada. Cuando los soldados como el joven Colin Powell se adentraron en Vietnam, no tardaron en comprender que la narrativa del rescate no se correspondía con la realidad. El enemigo resultó ser un pueblo resuelto y comprometido con su causa. Los aliados por los que luchaban las tropas de EE.UU. resultaron ser una burocracia corrupta y odiada, y la propia estrategia estadounidense demostró ser incapaz de cumplir su promesa de rescate.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

De pronto, esta narrativa patriota, frustrada por una aventura extranjera, viró bruscamente. Viró contra los que protestaban contra la guerra desde casa. Las tropas estadounidenses se abastecían sobre todo de las filas pobladas por negros pobres y blancos sureños pobres. Los jóvenes universitarios de clase media evitaron en su gran mayoría el servicio militar. Estos, sin embargo, fueron los que más alzaron la voz contra la guerra. Eran, en principio, los amigos y portavoces de las tropas que sufrían en el extranjero. Pero la práctica del patriotismo resultó ser otra muy distinta.

Sabemos, gracias a la investigación de personas como Robert Jay Lifton y Robert Howard, entre muchas otras, que las tropas en realidad se sentían acosadas desde dos frentes: en lo local, en el terreno, por los vietnamitas, y en lo simbólico, en casa, por estos amigos que protestaban. A los vietnamitas los consideraban enemigos patrióticos, y a los manifestantes que protestaban contra la situación en la que habían metido a las tropas los acusaban de ser antipatrióticos. A medida que se desvanecía la posibilidad de una victoria decisiva en el terreno, la posibilidad de obtener una victoria arrolladora sobre los enemigos que tenían en casa se fue tornando un vivo deseo. En 1968, relata Howard, en pleno auge de las protestas contra la guerra, miles de miembros de las tropas estadounidenses llevaban un mensaje en el casco: «América: la amas o la dejas».

La sensación de haber sufrido una traición desde dentro fortaleció cierta determinación, cierta «fantasía», en palabras de Lifton. El gobierno debería tomar cartas en el asunto para hacer callar a estos enemigos de dentro, de forma que pueda validarse el proyecto patriota. Y, en Estados Unidos, fue ese deseo del público de que los políticos actuasen de forma decisiva para sofocar el desorden interno y las protestas lo que puso en el poder a la derecha de Richard Nixon.

Repaso esta parte de la historia, en parte, porque arroja luz sobre los complejos ingredientes del sentimiento patriótico. No es que las tropas estadounidenses y las clases obreras del país fueran unos desgraciados, sino que estaban profundamente confundidos. Dentro de la cáscara de la guerra contra un enemigo interno, estas personas imaginaban otra guerra sucediendo en su propia nación, librada contra los traidores que fingían ser amigos. El acto arrollador de esa pugna interna por validar la narrativa patriótica sería silenciar el desacuerdo.

También recuerdo este pasado porque tal vez les ayude a ustedes a entender parte de las dinámicas existentes hoy día en la sociedad estadounidense. El lenguaje que se utiliza hoy en Washington sigue siendo un lenguaje de rescate, de redención, del triunfo del bien sobre el mal; e, igual que entonces, el escenario para esta narrativa, el escenario estratégico, carece de claridad o propósito. Pero echemos un vistazo a la condición doméstica del superpoder estadounidense. He aquí un país fragmentado e inconexo internamente, más incluso que hace 40 años. Confuso, por supuesto, y ahora furioso por los ataques terroristas contra él. Un país cuyas divisiones internas de clase se han hecho mayores y cuyas divisiones raciales y conflictos étnicos siguen sin sanar.

Al contrario que en Reino Unido —y es algo que creo que se trata de una fuente de malentendidos anglo-europeos—, a la izquierda de EE.UU. le falta el rol tradicional de una oposición leal. Y he terminado por creer que algunos elementos de la izquierda estadounidense han aprendido demasiado bien la lección que esbozo a partir de Vietnam. Esta izquierda se ha silenciado a sí misma, por miedo a que la oposición los descubra como malos americanos. Así es como se internaliza este síndrome.

Pensar a través de la narrativa es, por supuesto, un elemento básico en la interpretación del mundo diario, así como del mundo del arte. Y las narrativas en el mundo diario, al igual que las narrativas en el arte, no acatan un único cúmulo de reglas. Como en la ficción, las historias compartidas en la vida diaria no tienen por qué terminar en actos catárticos que sean represivos o destructores. Y, en mi opinión, el patriotismo ya no necesita seguir un único curso. Si los defectos tácticos de la estrategia estadounidense actual son tan insalvables como los de la guerra de Vietnam —y yo creo que lo son—, el reto para nuestro pueblo (y me refiero al pueblo americano) consistirá en evitar lo que ocurrió en Vietnam, sorteando la búsqueda de una catarsis narrativa, cuando nos miremos unos a otros en busca de una resolución, una solución, un momento decisivo.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Richard Sennett es Profesor de Sociología en la London School of Economics y en New York University. Esta es una versión editada de una charla presentada en el debate Index/Orange, Oxford, 2003.

This article originally appeared in the autumn 2003 issue of Index on Censorship magazine

Traducción de Arrate Hidalgo

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Rewriting America” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2003%2F09%2Frewriting-america%2F|||”][vc_column_text]Through a range of in-depth reporting, interviews and illustrations, the autumn 2003 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at the most powerful country in the world through the words of the people who know it best.

With: Tim Asher, Joel Beinin, Ioli Delivani[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”90596″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2003/09/rewriting-america/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

11 Dec 2017 | News, Volume 46.04 Winter 2017

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”Fifty years after 1968, the year of protests, increasing attacks on the right to assembly must be addressed says Rachael Jolley”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Close to where I live is a school named after an important protester of his age, John Ball. Ball was the co-leader of the 14th century Peasants’ Revolt, which looked for better conditions for the English poor and took to the streets to make that point. Masses walked from Kent to the edges of London, where Ball preached to the crowds. He argued against the poor being told where they could and couldn’t live, against being told what jobs they were allowed to pursue, and what they were allowed to wear. His basic demands were more equality, and more opportunity, a fairly modern message.

For challenging the status quo, Ball was put on trial and then put to death.

These protesters saw the right to assembly as a method for those who were not in power to speak out against the conditions in which they were expected to live and taxes they were expected to pay. In most countries today protest is still just that; a method of calling for change that people hope and believe will make life better.

However, in the 21st century the UK authorities, thankfully, do not believe protesters should be put to death for asserting their right to debate something in public, to call for laws to be modified or overturned, or for ridiculing a government decision.

Sadly though this basic right, the right to protest, is under threat in democracies, as well as, less surprisingly, in authoritarian states.

Fifty years after 1968, a year of significant protests around the world, is a good moment to take stock of the ways the right to assembly is being eroded and why it is worth fighting for.

In those 50 years have we become lazier about speaking out about our rights or dissatisfactions? Do we just expect the state to protect our individual liberties? Or do we just feel this basic democratic right is not important?

Most of the big leaps forward in societies have not happened without a struggle. The fall of dictatorships in Latin America, the end of apartheid, the right of women to vote, and more recently gay marriage, have partly come about because the public placed pressure on their governments by publicly showing dissatisfaction about the status quo. In other words, public protests were part of the story of major social change, and in doing so challenged those in power to listen.

Rigid and deferential societies, such as China, do not take kindly to people gathering in the street and telling the grand leaders that they are wrong. And with China racheting up its censorship and control, it’s no wonder that protesters risk punishment for public protest.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”Protecting protest is vital, even if it doesn’t feel important today. ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

But it is not just China where the right to protest is not being protected. Our special report on the UK discovers that public squares in Bristol and other major cities are being handed over to private companies to manage for hundreds of years, giving away basic democratic rights like freedom of speech and assembly without so much as a backwards glance.

Leading legal academics revealed to Index that it was impossible to track this shift of public spaces into private hands in detail, as it was not being mapped as it would in other Western countries. As councils shrug off their responsibilities for historic city squares that have been at the centre of shaping those cities, they are also lightly handing over their responsibilities for public democracy, for the right to assembly and for local powers to be challenged.

The Bristol Alliance, which already controls one central shopping district with a 250-year lease, is now seeking to take over two central thoroughfares as part of a 100,000-square-metre deal (see page 15). And the people who are deciding to hand them over are elected representatives.

In the USA, where a similar shift has happened with private companies taking over the management of town squares, the right to protest and to free speech has, in many cases, been protected as part of the deal. But in the UK those hard-fought-for rights are being thrown away.

Another significant anniversary in 2018 is the centenary of the right to vote for British women over 30. That right came after decades of protests. Those suffragettes, if they were alive today, would not look kindly on English city councils who are giving away the rights of their ancestors to assemble and argue in public arenas.

For a swift lesson in why defending the right to assembly is vital, look to Duncan Tucker’s report on how protesters in Mexico, Argentina, Venezuela and Brazil are facing increasing threats, tear gas and prison, just for publicly criticising those governments.

In Venezuela, where there are increasing food and medicine shortages, as well as escalating inflation, legislation is being introduced to criminalise protest.

As Tucker details on page 27 and 28, Mexican authorities have passed or submitted at least 17 local and federal initiatives to regulate demonstrations in the past three years.

Those in power across these countries are using these new laws to target minorities and those with the least power, as is typically the case throughout history. When the mainstream middle class take part in protest, the police often respond less dramatically. The lesson here is that throughout the centuries freedom of expression and freedom of assembly have been used to challenge deference and the elite, and are vital tools in our defences against corruption and authoritarianism. Protecting protest is vital, even if it doesn’t feel important today. Tomorrow when it is gone, it could well be too late.

But it is not all bad news. We are also seeing the rise of extreme creativity in bringing protests to a whole new audience in 2017. From photos of cow masks in India to satirical election posters from the Two-Tailed Dog Party in Hungary, new techniques have the power to use dangerous levels of humour and political satire to hit the pressure points of politicians. These clever and powerful techniques have shown protest is not a dying art, but it can come back and bite the powers that be on the bum in an expected fashion. And that’s to be celebrated in 2018, a year which remembers all things protest.

Finally, don’t miss our amazing exclusive this issue, a brand new short story by the award-winning writer Ariel Dorfman, who imagines a meeting between Shakespeare and Cervantes, two of his heroes.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Rachael Jolley is the editor of Index on Censorship magazine.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91582″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228808534472″][vc_custom_heading text=”Uruguay 1968-88″ font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228808534472|||”][vc_column_text]June 1988

In 1968 she was a student and a political activist; in 1972 she was arrested, tortured and held for four years; then began the years of exile.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94296″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228108533158″][vc_custom_heading text=”The girl athlete” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228108533158|||”][vc_column_text]February 1981

Unable to publish his work in Prague since the cultural freeze following the Soviet invasion in 1968, Ivan Klíma, has his short story published by Index. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”91220″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0306422017716062″][vc_custom_heading text=”Cement protesters” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1177%2F0306422017716062|||”][vc_column_text]June 2017

Protesters casting their feet in concrete are grabbing attention in Indonesia and inspiring other communities to challenge the government using new tactics.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row content_placement=”top”][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”What price protest?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2017%2F12%2Fwhat-price-protest%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In homage to the 50th anniversary of 1968, the year the world took to the streets, the winter 2017 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at all aspects related to protest.

With: Micah White, Ariel Dorfman, Robert McCrum[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”96747″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2017/12/what-price-protest/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″ css=”.vc_custom_1481888488328{padding-bottom: 50px !important;}”][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

30 Jun 2017 | Campaigns -- Featured, Digital Freedom, Digital Freedom Statements, Statements

Today, 84 organisations and individuals from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the USA sent letters to their respective governments insisting that government officials defend strong encryption. The letter comes on the heels of a meeting of the “Five Eyes” ministerial meeting in Ottawa, Canada earlier this week.

The “Five Eyes” is a surveillance partnership of intelligence agencies consisting of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. According to a joint communique issued after the meeting encryption and access to data was discussed. The communique stated that “encryption can severely undermine public safety efforts by impeding lawful access to the content of communications during investigations into serious crimes, including terrorism.”

In the letter organised by Access Now, CIPPIC, and researchers from Citizen Lab, 83 groups and individuals from the so-called “Five Eyes” countries wrote “we call on you to respect the right to use and develop strong encryption.” Signatories also urged the members of the ministerial meeting to commit to allowing public participating in any future discussions.

Read the letter in full:

Senator the Hon. George Brandis

Attorney General of Australia

Hon. Christopher Finlayson

Attorney General of New Zealand

Hon. Ralph Goodale

Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness of Canada

Hon. John Kelly

United States Secretary of Homeland Security

Rt. Hon. Amber Rudd,

Secretary of State for the Home Department, United Kingdom

CC: Hon. Peter Dutton, Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, Australia;

Hon. Ahmed Hussen, Minister of Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship, Canada;

Hon. Jeff Sessions, Attorney General for the United States;

Hon. Jody Wilson-Raybould, Minister of Justice and Attorney General, Canada;

Hon. Michael Woodhouse, Minister of Immigration, New Zealand

To Ministers Responsible for the Five Eyes Security Community,

In light of public reports about this week’s meeting between officials from your agencies, the undersigned individuals and organisations write to emphasise the importance of national policies that encourage and facilitate the development and use of strong encryption. We call on you to respect the right to use and develop strong encryption and commit to pursuing any additional dialogue in a transparent forum with meaningful public participation.

This week’s Five Eyes meeting (comprised of Ministers from the United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand, Canada, and Australia) discussed “plans to press technology firms to share encrypted data with security agencies” and hopes to achieve “a common position on the extent of … legally imposed obligations on … device-makers and social media companies to co-operate.” In a Joint Communiqué following the meeting, participants committed to exploring shared solutions to the perceived impediment posed by encryption to investigative objectives.

While the challenges of modern day security are real, such proposals threaten the integrity and security of general purpose communications tools relied upon by international commerce, the free press, governments, human rights advocates, and individuals around the world.

Last year, many of us joined several hundred leading civil society organisations, companies, and prominent individuals calling on world leaders to protect the development of strong cryptography. This protection demands an unequivocal rejection of laws, policies, or other mandates or practices—including secret agreements with companies—that limit access to or undermine encryption and other secure communications tools and technologies.

Today, we reiterate that call with renewed urgency. We ask you to protect the security of your citizens, your economies, and your governments by supporting the development and use of secure communications tools and technologies, by rejecting policies that would prevent or undermine the use of strong encryption, and by urging other world leaders to do the same.

Attempts to engineer “backdoors” or other deliberate weaknesses into commercially available encryption software, to require that companies preserve the ability to decrypt user data or to force service providers to design communications tools in ways that allow government interception are both shortsighted and counterproductive. The reality is that there will always be some data sets that are relatively secure from state access. On the other hand, leaders must not lose sight of the fact that even if measures to restrict access to strong encryption are adopted within Five Eyes countries, criminals, terrorists, and malicious government adversaries will simply switch to tools crafted in foreign jurisdictions or accessed through black markets. Meanwhile, innocent individuals will be exposed to needless risk. Law-abiding companies and government agencies will also suffer serious consequences. Ultimately, while legally discouraging encryption might make some useful data available in some instances, it has by no means been established that such steps are necessary or appropriate to achieve modern intelligence objectives.

Notably, government entities around the world, including Europol and representatives in the U.S. Congress, have started to recognise the benefits of encryption and the futility of mandates that would undermine it.

We urge you, as leaders in the global community, to remember that encryption is a critical tool of general use. It is neither the cause nor the enabler of crime or terrorism. As a technology, encryption does far more good than harm. We, therefore, ask you to prioritise the safety and security of individuals by working to strengthen the integrity of communications and systems. As an initial step, we ask that you continue any engagement on this topic in a multi-stakeholder forum that promotes public participation and affirms the protection of human rights.

We look forward to working together toward a more secure future.

Sincerely,

Access Now

Advocacy for Principled Action in Government

American Library Association

Amnesty International

Amnesty UK

Article 19

Australian Privacy Foundation

Big Brother Watch

Blueprint for Free Speech

British Columbia Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA)

Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA)

Canadian Journalists for Free Expression (CJFE)

Center for Democracy and Techology

Centre for Free Expression, Ryerson University

Chaos Computer Club (CCC)

Constitutional Alliance

Consumer Action

CryptoAustralia

Crypto.Quebec

Defending Rights and Dissent

Demand Progress

Digital Rights Watch

Electronic Frontier Foundation

Electronic Frontiers Australia

Electronic Privacy Information Center

Engine

Equalit.ie

Freedom of the Press Foundation

Friends of Privacy USA

Future Wise

Government Accountability Project

Human Rights Watch

i2Coalition

Index on Censorship

International Civil Liberties Monitoring Group (ICLMG)

Internet NZ

Liberty

Liberty Coalition

Liberty Victoria

Library Freedom Project

My Private Network

New America’s Open Technology Institute

NZ Council for Civil Liberties

OpenMedia

Open Rights Group (ORG)

NEXTLEAP

Niskanen Center

Patient Privacy Rights

PEN International

Privacy International

Privacy Times

Private Internet Access

Restore the Fourth

Reporters Without Borders

Rights Watch (UK)

Riseup Networks

R Street Institute

Samuelson-Glushko Canadian Internet Policy & Public Interest

Clinic (CIPPIC)

Scottish PEN

Subgraph

Sunlight Foundation

TechFreedom

Tech Liberty

The Tor Project

Voices-Voix

World Privacy Forum

Brian Behlendorf, executive director, Hyperledger, at the Linux Foundation

Dr. Paul Bernal, lecturer in IT, IP and media law, UEA Law School

Owen Blacker, founder and director, Open Rights Group; founder, NO2ID

Thorsten Busch, lecturer and senior research fellow, University of St Gallen

Gabriella Coleman, Wolfe Chair in scientific and technological literacy at McGill University

Sasha Costanza-Chock, associate professor of civic media, MIT

Dave Cox, CEO, Liquid VPN

Ron Deibert, The Citizen Lab, Munk School of Global Affairs

Nathan Freitas, Guardian Project

Dan Gillmor, professor of practice, Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Arizona State University

Adam Molnar, lecturer in criminology, Deakin University

Christopher Parsons, The Citizen Lab, Munk School of Global Affairs

Jon Penney, research fellow, The Citizen lab, Munk School of Global Affairs

Chip Pitts, professorial lecturer, Oxford University

Ben Robinson, directory, Outside the Box Technology Ltd and Discovery Technology Ltd

Sarah Myers Wes, doctoral candidate at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

J.M. Porup, journalist

Lokman Tsui, assistant professor at the School of Journalism and Communication, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (Faculty Associate, Berkman Klein Center)

19 Apr 2017 | Awards, Awards Update, Digital Freedom, News, Youth Board

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

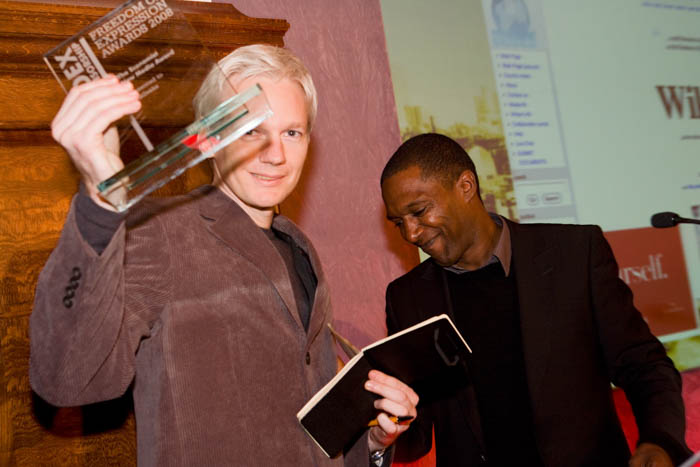

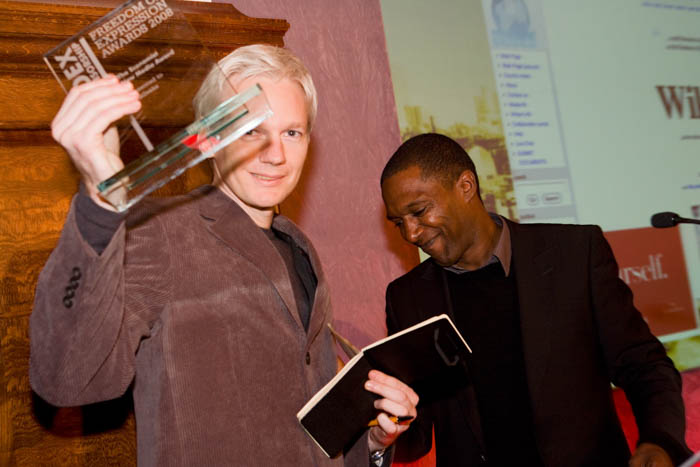

It has been over a decade since WikiLeaks released its cache of leaked documents and a little under a decade since it was awarded The Economist New Media Award at the 2008 Freedom of Expression Awards. In the following years, the non-profit organisation has published a considerable body of documents, holding to account states, corporations and individuals. Such actions would imply that it remains an apolitical organisation, whose mission is to ensure the defence of free speech and vitiation of censorship, although of late some would dispute its primary function. On the day of this year’s Dutch general election, WikiLeaks made separate Tweets with links to all documents referencing either Prime Minister Mark Rutte or right wing populist Geert Wilders.

Their fight for freedom of expression is often amorphous, which is well demonstrated by two publications from 2009. First, the March release of a website blacklist, proposed by Australia’s then communications minister, Stephen Conroy. Although it had been suggested by the Australian Government that the compulsory firewall would obstruct access to child pornography and sites related to terrorism, it was revealed to have included numerous websites which suggested a veiled political agenda. Second, the September release of an internal report on a toxic incident clean-up in the Ivory Coast by the oil trading company, Trafigura. That draft report was released after Trafigura obtained a super-injunction against The Guardian. Comparing the two, it is clear they share a commonality in combating instances of censorship, but beyond that an underlying characteristic in the material released is hard to find.

Where the organisation has had a focused, profound, and some would say not impartial, impact is on American politics. Three particularly notable moments were the 2010 Iraq and Afghanistan ‘War Logs’ and diplomatic cables associated with Chelsea Manning, the 2016 Democratic National Committee email leak, and the recent CIA Vault 7 release. It is perhaps the second of these that questions WikiLeaks’ apolitical position; in an interview with ITV, Julian Assange stated that he hoped the leaks would harm Hillary Clinton’s campaign. Certainly, the furore which surrounded Clinton’s use of a private email server in handling sensitive documents and the March 2016 release of her email archive was a boost for the Trump campaign. It remains to be seen whether the Trump administration or affiliated groups will be the subject of a WikiLeaks publication.

Whether one considers WikiLeaks a paragon, a zealot, or Machiavellian, it remains a powerful force against censorship. Although their profile has grown since being awarded The Economist New Media Award, they are still an organisation that appears wholly unconstrained by diplomatic pressures in holding bodies to account, who or whatever the target.

Samuel Rowe is a member of Index on Censorship’s Youth Advisory Board. He is currently a law conversion student at City, University of London, planning on practicing as a public law barrister with a focus in information law.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”85476″ img_size=”full” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/11/awards-2017/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards

Seventeen years of celebrating the courage and creativity of some of the world’s greatest journalists, artists, campaigners and digital activists

2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1492506268361-b3958523-724a-7″ taxonomies=”273, 8935″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]