Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

“This government has implicitly and explicitly targeted minorities in other areas, like the Windrush scandal,” academic Michael Bankole told Index. “So, it wouldn’t surprise me if it was a deliberate effort to erect barriers for minority voters when it comes to elections.”

Bankole, a Royal Holloway university lecturer specialising in race and British politics, was speaking to Index following the introduction of voter ID for England’s local elections in May 2023. Following this the Electoral Commission, the independent body which oversees elections in the UK, said that at least 3% of people didn’t vote because they lacked the necessary ID, and 14,000 people were turned away from polling stations for the same reason.

With low levels of proven electoral fraud in the UK, including no proven cases of in-person voter impersonation last year, questions have been raised about the introduction. This includes a potential impact on the ability of sections of society, including non-white voters, to cast their democratic vote, which is ultimately one of the most effective ways to have your voice heard.

Historically, non-white people have less access to some official forms of ID which are required for voting. For example, data from the Department of Transport showed that in 2021, 58% of the black population and 64% of the Asian population held a driving licence, compared to 79% of the white population.

Instead of focusing on voter ID at elections though, Bankole believes the focus should have been on why non-white voters have historically voted less overall. He said: “If we care about democracy, we want all members to participate in it, so it’s important to investigate why these groups are less likely to participate and what can be done to address that. That should’ve been the fundamental issue for the government to investigate.”

Following on from Bankole’s comments, the Electoral Commission’s interim report in June 2023 showed that 82% of Black and minority ethnic respondents (BME) were unaware of the need for voter ID in the recent elections compared to 93% of white respondents.

Looking over the pond to the USA, where encroaching voter ID laws have been enacted in individual states since 2006, academic studies have had time to focus on the effects. A study from 2018 argued that minorities in the USA are less likely to have valid forms of ID, with being born outside the USA and lower levels of education, income and home ownership as negatively affecting the chances of having valid ID. These issues generally affect minority voters more than white voters in the USA, where, as of 2023, 36 states require some form of ID to vote.

While academic studies have had time to focus on the effects of voter ID laws across the USA over the years, it’s not the case for the recent English elections. However, Democracy Volunteers, a group campaigning to improve the quality of democratic elections in the UK, deployed observers to 118 of the 230 councils holding elections and found that out of the 1.2% of voters they recorded as turned away for having no valid ID, 53% of these were recorded as “non-white passing” (described as such by the observers). In the 2021 census 18.3% of the residents of England and Wales described their ethnic group as something other than white. One of the observations from Democracy Volunteers’ report was that on a number of occasions people with valid ID from Commonwealth countries, such as Pakistan and Bangladesh, were turned away for having invalid ID. If the information from the report is correct, there is an issue. Index reached out to Democracy Volunteers to discuss the findings but received no response.

There was also controversy regarding what forms of ID were accepted during the elections. The older person’s bus pass, the Freedom Pass and the London 60+ Oyster card were accepted as valid ID (the first two eligible from the age of 66, the latter 60). There was no equivalent valid ID available for younger people. Bankole believes this had a political purpose: “For young people with transport ID, it wasn’t allowed, whereas for older voters, who disproportionally vote for the Conservatives, it was. I think they were erecting barriers for people who don’t vote for them and targeting their base who do.”

To put figures into context, 64% of voters aged 65+ voted for the Conservative Party in the last general election.

Along with the above, just 20% of non-white votes were cast for the Conservative Party at the 2019 UK general election, which it won by a landslide. Index contacted the Electoral Commission to ask if the introduction of the voter ID laws for the English elections was a form of gerrymandering (as a former British government cabinet member suggested). Also, because the majority of BME votes were for either the Labour or Liberal Democrats parties in the last general election, if the ID introductions were a deliberate effort to erect barriers for minority voters.

As well as announcing their interim report mentioned above, the response was as follows: “In September, we will publish our full report on the May 2023 elections. This report will feature further data, including the reasons people were turned away, as well as turnout, postal voting and rejected ballots. It will also provide analysis of other aspects of the elections, including accessibility support that was provided for voters in polling stations…As we’re still collecting data there isn’t more we can say at this stage.”

The next UK general elections will be held by January 2025, with the London Mayoral elections to be held by May 2024. With general elections traditionally attracting a far higher turnout than local government elections, and the electorate in London being the most ethnically diverse in the UK, voter ID issues could affect a greater number of non-white voters in the future. Voter ID information, along with any changes, is something that Index will keep an eye on in the future as we believe any barriers put in place to vote should be as low as possible, to make sure freedom of speech and expression is protected.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”118071″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]I am a woman kicked out of Heaven.

I am a writer tried for treason, facing life in prison.

I am an exile defined as others.

I am autistic, pushing myself to be normal.

Only to become invisible.

I’m 52 years old. Since childhood, I have always felt alienated from my environment. The more petulant I became, the more walls I built between myself and the world, the greater the desire to flee grew. Not knowing from whom and from what I’m running away, only having the desire to shelter somewhere else, anywhere else. It is hard to be weird and different to others but not know why.

It has done irreparable damage to my self-esteem. I felt trapped inside a cocoon woven of my unhappiness. I was a thing apart. Other people were strictly separate from me. I felt this separation keenly.

This distinction was so clear in my childhood, as a young girl and even now it is the same…

For years, I established completeness in my inner world with all my broken fragments. Without expectation, motionless, distant, introverted. I drowned in words, definitions, tasks… I forgot my essence. I learned to mask myself because I have always been judged.

I have a lot of voices in my mind, ghosts of decades-old voices. Telling me how I should be…

In 2011 I wrote an absurd play called Mi Minör set in a fictional country called Pinima. During the performance, the audience could choose to play the President’s deMOCKracy game or support the Pianist’s rebellion against the system. The Pianist starts reporting all the things that are happening in Pinima through Twitter, which starts a role-playing game (RPG) with the audience. Mi Minör was staged as a play where an actual social media-oriented RPG was integrated with the physical performance. It was the first play of its kind in the world.

A month after our play finished, the Gezi Park demonstrations in Istanbul started. On 10 June 2013, the pro-government newspaper Yeni Şafak came out bearing the headline ‘What A Coincidence’, accusing Mi Minör of being the rehearsal for the protests, six months in advance. The article continued, “New information has come to light to show that the Gezi Park protests were an attempted civil coup” and claimed that “the protests were rehearsed months before in the play called Mi Minör staged in Istanbul”.

After Yeni Şafak’s article came out, the mayor of Ankara started to make programmes on TV specifically about Mi Minör, mentioning my name.

In one he showed an edited version of one of the speeches that I made six years ago about secularism, misrepresenting what I said in such a way that it looked like I was implying that secularism was somehow antagonistic to religion.

What I found so brutal was that the mayor did this in the knowledge that religion has always been one of the most sensitive subjects in Turkey. What upset me most was the fear I witnessed in my son’s eyes and the anxiety that my partner was living through.

Arikan interviewed over Mi Minor

The play was being discussed regularly on TV, websites and online forums and both Mi Minör and my name were being linked to a secret international conspiracy against Turkey and its ruling party, the AKP. Many of the comments referenced the 2004 banning of my book Stop Hurting my Flesh. I received hundreds of emails and tweets threatening rape and death as a result of this campaign.

For three nightmarish months, we were trapped in our own house and did not set foot outside. One day, I saw that one of my prominent accusers was tweeting about me for four hours. The sentences he chose to tweet were all excerpts from my research publication The Body Knows, taken out of context and manipulating what I had written. Those tweets were the last straw.

I left our house, our loved ones, our pasts. We left in a night with a single suitcase and came to Wales, which had always been my dream country. I never imagined my arrival in Cardiff would be like this; feeling bitter, broken and incomplete.

Two years later my partner, who had remained in Turkey, and I got married. In the first month, I learned my husband had brain cancer. Operations, chemotherapy, radiotherapy followed… Within a year, I lost him. I visited him, but sadly I wasn’t able to go to his funeral because of new accusations levelled against me. This was a turning point in my life. I lost my husband. I lost my trust in people. I lost my savings to pay for his care. I lost everything.

In all of this emotional turmoil, I started walking every day for five or six hours. Geese became my best friend and my remedy. I walked for months. I walked and walked everywhere, in the mountains, in the valleys, at the seaside.

These walks had a transformative effect on me. I had discovered a way to live as a woman who had learned to accept herself, rather than a shattered and a lost woman.

Maybe there is an umbilical cord, beyond my consciousness, between me and the wild nature of Wales. I feel this land always wrapped itself around me, talked to me like a mother during the difficult time in my life. For this reason, I wrote my latest play; Y Brain/Kargalar (Crows), written in Welsh and Turkish and produced by Be Aware Productions. It describes my story, the special place this land has in my life and how it transformed me. The title refers to my constant companions during this time – the crows. One reviewer called it “unashamedly lyrical…even as it touches on dark themes”.

On 20 February 2019, as the play was being staged, a new indictment was issued against 16 people, including me, over Mi Minör; I now face a life sentence. Because of this absurd accusation, I feel ever more strongly that Wales is protecting me.

It was at this time that I was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome/autistic spectrum disorder and I’ve received many answers about myself as a result. From this moment, a new discovery and understanding started. I set out to discover myself with this new knowledge. As soon as I could know who I’m not, I could find out who I am.

I realise that my wiring system simply makes it harder for me to do many things that come naturally to other people. On the flip side, it is important to be aware that autism can also give me many magical perceptions that many neurotypicals simply are not capable of. I believe I was able to write Mi Minör because of my different perceptions.

I have therapy twice a week and I have started to understand what I have been through all my life. My therapists told me that I was manipulated and I was emotionally and sexually abused by whom I love and trust the most; it was a big shock for me. I spent half of my life trying to help abused victims, and I never thought I was a victim. They said this is very common because autistic women are not aware of when they were used. How could I have been so blind?

I couldn’t work out that I was being played by others, like a fish on a line. As an autistic, communication is about interpreting with a basic belief in what people tell me because I don’t tell lies myself. But I have learned how much capacity for lies exists. Autistic people can be gullible, manipulated and taken advantage of. But I learned that regret is the poison of life, the prison of the soul.

The most significant benefit of this process is that I am learning again like a child to re-evaluate everything with curiosity and enthusiasm. It also gives me the chance to reconstruct the rest of my life without hiding myself, being subjugated to anyone, and living without fear.

Autism diagnosis and discovery were liberating for me. There is still not enough autism spectrum awareness even today. That is why I decided to come out about my autism. I strongly believe that if those of us who are on the autistic spectrum share our experiences openly, then it wouldn’t only help other autistic people, it would help neurotypical people to better understand both us and our behaviour.

Looking back at the last few years, I have been thrown into navigating most of the challenging aspects and life experiences and there has been a complete cracking of all masks.

This process is not easy at all, sometimes my soul, sometimes my heart, sometimes all my cells hurt, but it also causes me to recognise a liberation I have never known before.

Fortunately, during this process, I have been learning a lot about myself and how I have masked myself as an Aspie-woman… For me, masking myself is more harmful even than not knowing I’m autistic. Masking means that I create a different Meltem to handle every situation. I have never felt a strong connection with my core. When I am confronted with emotional upset, my brain immediately goes into “fix it” mode, searching for a way to make the other person feel better so I can also relieve my own distress.

For most of my life, I’ve allowed myself to fit in with how I thought others wanted me to feel and act, especially those I loved. My dark night gave me so much pain I broke free and started to care for myself and heal. Taking me back to my primordial self, not the heroic one that burns out, to step back from the battle line of existence, to remember the gods and spiritual parts of nature, my own nature and the person I was at the beginning.

The last two years have been exciting for me. It is as if I died and was reincarnated again. In the end, I understand that my true nature is not to be some ideal that I have to live up to. It’s ok to be who I am right now, and that’s what I can make friends with and celebrate. I learned it’s about finding my own true nature and speaking and acting from that. Whatever our quality is, that’s our wealth and our beauty. That’s what other people respond to. I’m not perfect, but I’m real…[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116924″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]In celebration of one of football’s biggest international tournaments, here is Index’s guide to the free speech Euros. Who comes out on top as the nation with the worst record on free speech?

It’s simple, the worst is ranked first.

We start today with Group A, which plays the deciding matches of the group stages today.

Turkey’s record on free speech is appalling and has traditionally been so, but the crackdown has accelerated since the attempted – and failed – military coup of 2016.[1][2]

The Turkish government, led by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has attacked free speech through a combination of closing down academia and free thought and manipulating legislation to target free speech activists and the media. He has also ordered his government to take over newspapers to control their editorial lines, such as the case with the newspaper Zaman, taken over in 2014.[3]

Some Turkish scholars have been forced to inform on their colleagues[4] and Erdoğan also ordered the closing down of the prominent Şehir University in Istanbul in June 2020[5].

But it is manipulation of legislation that is arguably the arch-weapon of the Turkish government.

A recent development has seen the country use Law 3713, Article 314 of the Turkish Penal Code and Article 7 of the Anti-Terror Law to convict both human rights activists and journalists.

As of 15 June this year, a total of 12 separate cases of under Law 3173[6] have seen journalists currently facing prosecution, merely for being critical of Turkey’s security forces.

This misuse of the law has caused worldwide condemnation from the European Union, the United Nations and the Council of Europe, among many others[7].

Misuse of anti-terrorism legislation is a common tactic of oppressive regimes and is reflective of Turkey’s overall attitude towards freedom of speech.

Turkey also has a long history of detaining dissenting forces and is notorious for its dreadful prison conditions. Journalist Hatice Duman, for example, has been detained in the country since 2003[8]. She has been known to have been beaten in prison.[9]

Leading novelists have also been attacked. In 2014, the pro-government press accused two authors, Elif Shafak and Orhan Pamuk were accused of being recruited by Western powers to be critical of the government.[10]

Every dissenting voice against the government in Turkey is under scrutiny and authors, journalists and campaigners easily fall foul of the country’s disgraceful human rights record.

With a rank of 153rd on Reporters Without Borders’ 2021 World Press Freedom Index, it is also the worst-placed team in the tournament in this regard.

Freedom of speech in Italy was enshrined in the 1948 constitution after the downfall of fascist dictator Benito Mussolini in 1945. However, a combination of the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, oppressive legislation and violent threats to journalists means that its record is far from perfect.

Slapps (strategic lawsuits against public participation) are used by governments and big corporations as a form of intimidation against journalists and are common in Italy.

Investigative journalist Antonella Napoli told Index of the difficulty journalists such as her face due to Slapps. She herself is facing a long-running suit, which first arose in 1998. She will face her next hearing on the issue in 2022[11].

She said: “We investigative journalists are under the constant threat of litigation requires determination to continue our work. A pressure that few can endure.”

“When happen a similar case you feel gagged, tied, especially if you are a freelance journalist. If you get your hands on big news about a public figure with the tendency to sue, you’ll think twice. I have never stopped, but many give up because they fear consequences that they can’t afford.”

Italy bore the brunt of the early stages of the pandemic in Europe. Often, when governments experience nationwide crises, they use certain measures to implement restrictive legislation that cracks down on journalism and free speech, inadvertently or not.

The decree, known as the Cura Italia law, meant that typical tools for journalists, or any keen public citizen, such as Freedom of Information requests were hard to come by unless deemed absolutely necessary.

Aside from Covid-19 restrictions, Italy continues to have a problem with the mafia. There are currently 23 journalists under protection in the country.[12]

Wales is very much subject to the mercy of Westminster when it comes to free speech

Arguably, the most concerning development is the Online Safety Bill (also known as ‘online harms’), currently in its white paper stage.

While there are, sadly, torrents of online abuse, this attempt to regulate speech online is concerning.

The draft bill contained language such as “legal but harmful” means there would be a discrepancy between what is illegal online, versus what would be legal offline and thus a lack of consistency in the law regarding free speech.

The world of football recently took part in an online social media blackout, instigated in part by Welsh club Swansea City on 8 April[13], following horrific online racial abuse towards their players.

Swansea said: “we urge the UK Government to ensure its Online Safety Bill will bring in strong legislation to make social media companies more accountable for what happens on their platforms.”[14]

But the boycott was criticised with some, including Index, concerned about the ramifications pushing for the bill could have.

In 2020, Index’s CEO Ruth Smeeth explained what damage the legislation could cause: “The idea that we have something that is legal on the street but illegal on social media makes very little sense to me.”[15]

Switzerland has an encouraging record for a country that only gave women the vote in 1971.

They rank 10th on RSF’s World Press Freedom Index and have, generally speaking, a positive history regarding free speech and freedom of the press.

But a recent referendum may prove to be an alarming development.

Frequently, where there may be unrest or a crisis in a country, government’s use anti-terrorism laws to their own advantage. Voices can be silenced very quickly.

On 13 June, Switzerland voted to give the police detain people without charge or trial[16] under the Federal Law on Police Measures to Combat Terrorism.

Amnesty International Switzerland’s Campaign Director, Patrick Walder said the measures were “not the answer”.

“Whilst the desire among Swiss voters to prevent acts of terrorism is understandable, these new measures are not the answer,” he said. “They provide the police with sweeping and mostly unchecked powers to impose harsh sanctions against so-called ‘potential terrorist offenders’ and can also be used to target legitimate political protest.”

“Those wrongly suspected will have to prove that they will not be dangerous in the future and even children as young as 12 are at risk of being stigmatised and subjected to coercive measures by the police.”

56.58 per cent came out in support of the measures.[17]

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jW_c30hwXTM&ab_channel=Vox

[2] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306422020917614

[3] https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2016/03/turkey-fears-of-zaman-newspaper-takeover/

[4] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306422020917614

[5] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0306422020981254

[6] https://rsf.org/en/news/turkey-using-terrorism-legislation-gag-and-jail-journalists

[7] https://stockholmcf.org/un-calls-on-turkey-to-stop-misuse-of-terrorism-law-to-detain-rights-defenders/

[8] https://cpj.org/data/people/hatice-duman/

[9] https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2021/01/the-desperate-situation-for-six-people-who-are-jailednotforgotten/

[10] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/dec/12/pamuk-shafak-turkish-press-campaign

[11] https://www.balcanicaucaso.org/eng/Areas/Croatia/Croatia-and-Italy-the-chilling-effect-of-strategic-lawsuits-197339

[12] https://observatoryihr.org/iohr-tv/23-journalists-still-under-police-protection-in-italy/

[13] https://twitter.com/SwansOfficial/status/1380113189447286791?s=20

[14] https://www.swanseacity.com/news/swansea-city-join-social-media-boycott

[15] https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2020/09/index-ceo-ruth-smeeth-speaks-to-board-of-deputies-of-british-jews-about-censorship-concerns/

[16] https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/freedom-of-expression–universal–but-not-absolute/46536654

[17] https://lenews.ch/2021/06/13/swiss-vote-in-favour-of-covid-laws-and-tougher-anti-terror-policing-13-june-2021/[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

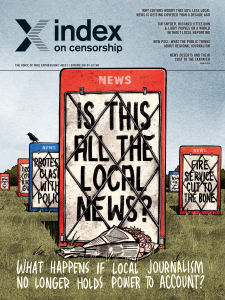

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”97% of editors of local news worry that the powerful are no longer being held to account ” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][vc_column_text]

Ninety seven per cent of senior journalists and editors working for the UK’s regional newspapers and news sites say they worry that that local newspapers do not have the resources to hold power to account in the way that they did in the past, according to a survey carried out by the Society of Editors and Index on Censorship. And 70% of those respondents surveyed for a special report published in Index on Censorship magazine are worried a lot about this.

The survey, carried out in February 2019 for the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine, asked for responses from senior journalists and current and former editors working in regional journalism. It was part of work carried out for this magazine to discover the biggest challenges ahead for local journalists and the concerns about declining local journalism has on holding the powerful to account.

The survey found that 50% of editors and journalists are most worried that no one will be doing the difficult stories in future, and 43% that the public’s right to know will disappear. A small number worry most that there will be too much emphasis on light, funny stories.

There are some specific issues that editors worry about, such as covering court cases and council meetings with limited resources.

Twenty editors surveyed say that they feel only half as much local news is getting covered in their area compared with a decade ago, with 15 respondents saying that about 10% less news is getting covered. And 74% say their news outlet covers court cases once a week, and 18% say they hardly ever cover courts.

The special report also includes a YouGov poll commissioned for Index on public attitudes to local journalism. Forty per cent of British adults over the age of 65 think that the public know less about what is happening in areas where local newspapers have closed, according to the poll.

Meanwhile, 26% of over-65s say that local politicians have too much power where local newspapers have closed, compared with only 16% of 18 to 24-year-olds. This is according to YouGov data drawn from a representative sample of 1,840 British adults polled on 21-22 February 2019.

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-quote-left” color=”custom” size=”xl” align=”right” custom_color=”#dd3333″][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_custom_heading text=”The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” google_fonts=”font_family:Libre%20Baskerville%3Aregular%2Citalic%2C700|font_style:400%20italic%3A400%3Aitalic”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]The Index magazine special report charts the reduction in local news reporting around the world, looking at China, Argentina, Spain, the USA, the UK among other countries.

Index on Censorship editor Rachael Jolley said: “Big ideas are needed. Democracy loses if local news disappears. Sadly, those long-held checks and balances are fracturing, and there are few replacements on the horizon. Proper journalism cannot be replaced by people tweeting their opinions and the occasional photo of a squirrel, no matter how amusing the squirrel might be.”

She added: “If no local reporters are left living and working in these communities, are they really going to care about those places? News will go unreported; stories will not be told; people will not know what has happened in their towns and communities.”

Others interviewed for the magazine on local news included:

Michael Sassi, editor of the Nottingham Post and the Nottingham Live website, who said: “There’s no doubt that local decision-makers aren’t subject to the level of scrutiny they once were.”

Lord Judge, former lord chief justice for England and Wales, said: “As the number of newspapers declines and fewer journalists attend court, particularly in courts outside London and the major cities, and except in high profile cases, the necessary public scrutiny of the judicial process will be steadily eroded,eventually to virtual extinction.”

US historian and author Tim Snyder said: “The policy thing is that government – whether it is the EU or the United States or individual states – has to create the conditions where local media can flourish.”

“A less informed society where news is replaced by public relations, reactive commentary and agenda management by corporations and governments will become dangerously volatile and open to manipulation by special interests. Allan Prosser, editor of the Irish Examiner.

“The demise of local reporting undermines all journalism, creating black holes at the moment when understanding the “backcountry” is crucial. Belgian journalist Jean Paul Marthoz.

The special report “Is this all the local news? What happens if local journalism no longer holds power to account?” is part of the spring issue of Index on Censorship magazine.

Note to editors: Index on Censorship is a quarterly magazine, which was first published in 1972. It has correspondents all over the world and covers freedom of expression issues and censored writing

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Is this all the Local News?” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2018%2F12%2Fbirth-marriage-death%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The spring 2019 issue of Index on Censorship magazine explores what happens to democracy without local journalism, and how it can survive in the future.

With: Richard Littlejohn, Libby Purves and Tim Snyder[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_single_image image=”105481″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2018/12/birth-marriage-death/”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:h3|text_align:left”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row]