Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”116596″ img_size=”full” add_caption=”yes”][vc_column_text]A British oil industry whistleblower was detained last night by armed police in Zagreb and held overnight against his will in a psychiatric hospital after British diplomats raised concerns about his mental health.

Jonathan Taylor has been stranded in Croatia since July last year, when he was arrested while entering the country for a holiday with his family. The authorities in Monaco, where he worked for oil company SBM Offshore, have accused him of extortion and requested his extradition to the Principality. He is awaiting a decision from the Croatian Supreme Court this week.

In 2013, Taylor blew the whistle on a multimillion dollar network of bribery payments made by SBM around the world and cooperated with prosecutors in the UK, the US, Brazil and the Netherlands. These investigations resulted in fines against the company to the tune of $827 million and the conviction of two former CEOs of SBM for fraud-related offences. However, Monaco has decided to target the whistleblower rather than those responsible for the bribes.

Freedom of expression organisations, including Index on Censorship, have been lobbying the British government to put pressure on Monaco and Croatia to allow Taylor to return England where his family is now based. Media Freedom Rapid Response partners have demanded an end the extradition proceedings.

Taylor had alerted the British Embassy and the Sofia-based regional consul last Friday about his deteriorating mental health and was asked to put his thoughts into writing. This set off a train of events in Zagreb that Jonathan Taylor relates in his own words here:

“I was met by two armed officers at the roadside to the entrance of the forecourt to my apartment at about 9:15pm last night. I was told I had to wait with them until a psychiatrist arrived in an ambulance. After about 45 minutes we went up to my apartment as it had started raining and the ambulance still hadn’t arrived.

“At about 10:15pm the ambulance drivers arrived and joined the two policemen in my apartment. I was then told I had to accompany them to hospital. I protested stating I had been told a psychiatrist would come to me. I made it clear I was not prepared to leave the apartment. Then four more other armed officers arrived. I again explained I was not happy to go to hospital (see picture top).

“Eventually two of the armed officers manhandled me to the ground causing my head to hit a wall and a resulting headache. I was the cuffed with face against the floor and manhandled out of my apartment into an ambulance where I was strapped into a stretcher. Upon arrival at hospital (no idea where I am) I was dragged out of ambulance and sat on a chair just inside the door to the hospital. I was left there under guard, still handcuffed, for about 30 minutes.

“A lady came to see me (apparently a psychiatrist, but she did not introduce herself) and she asked a few basic questions like ‘why did I arrive with the police?’ and ‘how long had they been following me?’ (!).

“Shortly after this I was taken to a room, still cuffed, where I was strapped to a bed by my feet and legs and my hands. I then refused unidentified tablets and was invited to swallow them whilst someone held a cup of water to my mouth. I refused. I was then forcibly turned and something was injected into my upper thigh. It was now at least 12:30am. At about 6:30am, again against my will, I had a further injection. Another psychiatrist came to see me at about 10:15am and she determined I could go…

“A smiling male nurse has just prodded my arm saying ‘everything will be OK, don’t hate Croatia now!” I have just discovered that I am at the University Hospital Vrapte. What to say?…Where I was looking for help, I got one of the worst twelve-hour experiences of my life.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][three_column_post title=”You may also want to read” category_id=”256″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

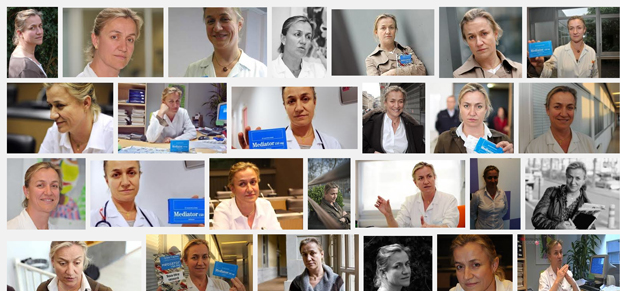

Irène Frachon is a French pneumologist who discovered that an antidiabetic drug frequently prescribed for weight loss called Mediator was causing severe heart damage.

The French term “lanceur d’alerte” [literally: “alarm raiser”], which translates as “whistleblower”, was coined by two French sociologists in the 90’s and popularised by scientific André Cicolella, a whistleblower who was fired in 1994 from l’Institut national de recherche et de sécurité [the National institute for research and security] for having blown the whistle on the dangers of glycol ethers.

While the history of whistleblowing in the United States is closely associated with the case of Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers to The New York Times in 1971, exposing US government lies and helping to end the Vietnam war, whistleblowing in France was first associated with cases of scientists who raised the alarm over a health or an environmental risk.

In England, the awareness that whistleblowers needed protection grew in the early 1990s, after a series of accidents (among which the shipwreck of the MS Herald of Free Enterprise ferry, in 1987, which caused 193 deaths) when it appeared that the tragedies could have been prevented if employees had been able to voice their concerns without fear of losing their job. The Public Interest Disclosure Act, passed in 1998, is one of the most complete legal frameworks protecting whistleblowers. It still is a reference.

France had no shortage of national health scandals in the 1990s, from the case of HIV-contaminated blood to the case of growth hormone. But no legislation followed. For a long time, whistleblowers were at the center of a confusion: their action was seen as reminiscent of the institutionalised denunciations that took place under the Vichy regime when France was under Nazi occupation. In fact, no later than this year, some conservative MPs managed to defeat an amendment on whistleblowers’ protection by raising the spectre of Vichy.

For Marie Meyer, Expert of Ethical Alerts at Transparency International, an anti-corruption NGO, this confusion makes little sense: “Whistleblowing is heroic, snitching cowardly”, she says.

“In France, the turning point was definitely the Mediator case, and Irène Frachon,” Meyer adds, referring to the case of a French pneumologist who discovered that an antidiabetic drug frequently prescribed for weight loss called Mediator was causing severe heart damage. In 2010, Frachon published a book – Mediator, 150mg, Combien de morts ? [“Mediator, 150mg, How Many Deaths?”] – where she recounted her long fight for the drug to be banned. Servier, the pharmaceutical company which produced the drug, managed to censor the title of the book and get it removed from the shelves two days after publication, before the judgement was overturned. Frachon has been essential in uncovering a scandal which is believed to have caused between 500 and 2000 deaths. With scientist André Cicolella, she has become one of the better-known French whistleblowers.

“What is striking is that people knew, whether in the case of PIP breast implants or of Mediator”, says Meyer. “You had doctors who knew, employees who remained silent, because they were scared of losing their job.”

This year, the efforts of various NGOs led by ex whistleblowers were finally met with results. Last January, France adopted a law (first proposed to the Senate by the Green Party) protecting whistleblowers for matters pertaining to health and environmental issues. The Cahuzac scandal, which fully broke in February and March, prompting the minister of budget to resign over Mediapart’s allegations that he had a secret offshore account, was instrumental in raising awareness and created the political will to protect whistleblowers.

For Meyer, France’s failure to protect whistleblowers employed in the public service has had direct consequences on the level of corruption in the country.

“Even if a public servant came to know that something was wrong with the financial accounts of a Minister, be it Cahuzac or someone else, how could he have had the courage to say it, and risk for his career and his life to be broken?” she says.

In June, as France discovered Edward Snowden’s revelations in the press over mass surveillance programs used by the National Security Agency, it started rediscovering its own whistleblowers: André Cicolella, Irène Frachon or Philippe Pichon, who was dismissed as a police commander in 2011 after his denunciations on the way police files were updated. Banker Pierre Condamin-Gerbier, a key witness in the Cahuzac case, was recently added to the list, when he was imprisoned in Switzerland on the 5th of July, two days after having been heard by the French Parliamentary Commission on the tax evasion case.

Three new laws protecting whistleblowers’ rights should be passed in the autumn. France will still be missing an independent body carrying out investigations into claims brought up by whistleblowerss, and an organisation to support them, like British charity Public Concern at Work does in the UK.

So far, French law doesn’t plan any particular protection to individuals who blow the whistle in the press, failing to recognise that, for a whistleblower, communicating with the press can be the best way to make a concern public – guaranteeing that the message won’t be forgotten, while possibly seeking to limit the reprisal against the messenger.

South Africa’s Right2Know Campaign (R2K) is “Camping out for Openness” outside parliament in Cape Town this week as deliberations over the draconian Protection of State Information Bill draw to a close.

The National Council of Provinces, the second house of parliament, is due to adopt the bill by the end of November. The bill is ostensibly aimed at instituting a long-overdue system to regulate access to government documents.

However, despite persistent appeals from, among others, luminaries such as Nobel Laureate Nadine Gordimer, the Secrecy Bill’s system of classification and declassification has not been couched in the country’s constitutional commitment to an open democracy and the free flow of information.

Instead it opens the door to the over-classification of state information while instituting harsh punishments for the possession of classified information, undermining basic citizenship rights.

Pressure from civil society, led by the R2K Campaign, produced limited concessions this year. One of the most pertinent demands was to include a public interest defence clause to ameliorate the anti-democratic effects of the bill. The ruling African National Congress (ANC) eventually conceded by allowing a clause enabling a public interest defence, but only if the disclosure revealed criminal activity. This has been criticised as an unreasonably high threshold.

Right2Know march in Pretoria, South Africa, September 2012. Jordi Matas | Demotix

The ANC this month backtracked on two other key concessions, as pressure from state security minister Siyabonga Cwele on ANC parliamentarians seemingly paid off:

Cwele’s predecessor, Ronnie Kasrils, this week addressed the R2K camp outside parliament, distancing himself from what he deemed the “devious” and “toxic” bill. While he was minister, he withdrew the 2008 version of the bill after a similar outcry about its lack of constitutionality.

According to R2K, the other remaining problems with the Secrecy Bill include:

Parliament’s engagement with the bill, which started in July 2010, has been characterised by Orwellian “doublethink”, as exemplified in Cwele’s declaration that “protect(ing) sensitive information … is the oil that lubricates our democracy and we have no intention — not today, not ever — to undermine the freedom we struggled and sacrificed for all these years”.

R2K has vowed to continue pressuring parliamentarians to replace the Secrecy Bill with a law “that genuinely reflects a just balance between the public’s right to know and [the] government’s need to protect limited state information”.

Christi van der Westhuizen is Index on Censorship’s new South Africa correspondent

Former IDF soldier Anat Kamm’s 4.5 year prison sentence shows the contradictions of Israel’s attitude towards leaks. Elizabeth Tsurkov reports

Former IDF soldier Anat Kamm’s 4.5 year prison sentence shows the contradictions of Israel’s attitude towards leaks. Elizabeth Tsurkov reports

When the Tel Aviv District Court sentenced Anat Kamm to four-and-a-half years in prison for leaking classified documents she obtained during her IDF service to the daily Haaretz, few Israelis were bothered. And no wonder, as Kamm was branded as a traitor and a spy by the security establishment, and most pundits since the gag order on her case had been lifted in April 2010. Most of the Israeli public didn’t seem concerned about the consequences this sentence will have on press freedom in Israel, but this lack of concern doesn’t make the repercussions of this sentence any less real.

Journalists rely on leaks and sources willing to talk to them and share information, which at times are obtained illegally and is disclosed without permission. The Israeli press is strewn with leaks, most of which are the product of political fights and bickering, and their purpose is to harm political rivals, not scrutinise the security establishment.

For example, in late 2006, Prime Minister Olmert attacked his Defence Minister Peretz for a phone call he had with Palestinian Authority President Abbas without informing Olmert himself.The attack revealed top secret information, namely that Israel wiretaps the phones of Abbas.

The Kamm verdict stated that it wasn’t necessary for the prosecution to prove harm was done to Israel’s security as a result of the leak, and the mere possibility of such harm was enough to convict Kamm. Judging by this standard, Olmert’s leak of highly sensitive information solely for political purposes was surely harmful Israel’s security.

Other common forms of leaks in the country are authorised declassifications by security services or leaks by government officials, which are intended to serve the political goals of the state of Israel. The occasional leaks by unnamed Israeli government official about the country’s intentions to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities are an example for such calculated moves, which are intended to spur the international community into action against Iran. Both these forms of leaks, the ones caused by political infighting and the calculated declassification, under the appearance of free press, are intended to serve the establishment, or at least the parts of it that leaked the information. These leaks provide a one-sided view of reality, according to the interests of the leaking party, and rarely serve any oversight capacity.

Israeli media rarely reports critically on the IDF, let alone other security organs, partly out of misplaced patriotism, but also because Israeli media lacks sources that are willing to reveal information about wrongdoings of the country’s security establishment. Critical coverage and public accountability of the security services are all the more necessary considering the little oversight the Knesset has over the security establishment due to issues of security clearances, and the culture of impunity that pervades Israel’s security organs.

Several of the documents Kamm provided to Haaretz reporter Uri Blau showed the IDF was still carrying out targeted assassinations of Palestinians suspected of terrorist activity when their capture was possible, against the explicit ruling of the Supreme Court. The officers who ordered and approved this illegal policy were not charged by the Attorney General. Instead, Israel’s justice system chose to punish a person who attempted to fight the IDF’s culture of impunity and disregard for the law.

Elizabeth Tsurkov is an Israeli writer and a contributor to +972 Magazine and Global Voices Online. You can follow her on Twitter: @elizrael.